Lingue senza aggettivi? - Grandionline.net

Lingue senza aggettivi? - Grandionline.net

Lingue senza aggettivi? - Grandionline.net

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Lingue</strong> <strong>senza</strong> <strong>aggettivi</strong>?<br />

Mark Post (2008), Adjectives in Thai: Implications<br />

for a functionalist typology od word classes,<br />

Linguistic Typology, 12:3, 339-381<br />

<strong>Lingue</strong> del Sud Est asiatico: <strong>senza</strong> <strong>aggettivi</strong>?<br />

No, se si assume l’idea che le parti del discorso<br />

siano universalmente definite essenzialmente in<br />

base alla condivisione di funzioni pragmatiche

Adjective classes are nowadays routinely identified as prototypically<br />

containing words denoting property concepts (p. 341)<br />

concetti graduabili: <strong>aggettivi</strong><br />

concetti non graduabili: nomi e verbi<br />

Fundamentally, the semantic property of gradability would seem to lend<br />

adjectives an aptness for degree modification (more / less, a lot / little,<br />

the most / least), for lexicalization as points on a property scale (tiny,<br />

small, big, huge,…), as well as for comparison in terms of the relative<br />

degree of properties exhibited by two referents (p. 341)

Dixon, R. M. W. (1977), Where have all the adjectives gone?, “Studies in<br />

Language”, 1, 19–80<br />

Dixon, R. M. W. / Aikhenvald, A. Y. (eds.) (2004), Adjective Classes. A Cross-<br />

Linguistic Typology, Oxford, Oxford University Press<br />

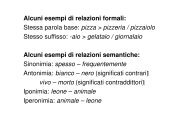

CORE:<br />

Dimension (big, small…)<br />

Age (new, old…)<br />

Value (good, bad…)<br />

Colour (black, white…)<br />

PERIPHERY:<br />

Physical property (hard, soft…)<br />

Human propensity (happy, sad…)<br />

Speed (fast, slow…)<br />

Functionally, adjectives prototipically attribute features to a referent

Adjectives are often viewed as inherently mono-relational, in the semantic sense<br />

that their denotation may be viewed as incomplete without simultaneous construal<br />

of some entity or set which exhibits the stated property (e.g. a man who is tall), and<br />

in the syntactic sense that they either project (as predicate), cooccur with (as<br />

copula complement), or depend on (a modifier) one and only one referring<br />

expression.<br />

Thai<br />

Terms denoting properties are primarily divisible into<br />

-Verblike forms (the vast majority)<br />

- Nounlike forms

Verblike properties include terms from all of the core and peripheral semantis fields:<br />

dii ‘good’<br />

jεεÎ ‘bad’<br />

rO´On ‘hot’<br />

naÍaw ‘cold’<br />

Nounlike property concepts mainly correspond to the fields of PHYSICAL PROPERTY,<br />

HUMAN PROPENSITY, and COLOUR:<br />

thammachaÎat ‘natural(ness)’<br />

sùantua ‘private/privacy’<br />

saniÍm ‘rust(y)’

Proprietà distribuzionali<br />

Verblike property concepts occur as intransitive predicate and do not occur as<br />

copula complement<br />

Khon níi dəən<br />

CLF:person PRX walk<br />

‘This person walks’ (active verb, intransitive predicate)<br />

*Khon níi pen dəən<br />

CLF:person PRX ACOP walk<br />

‘This person walks’ (active verb, intransitive predicate)<br />

Khon níi dii<br />

CLF:person PRX good<br />

‘This person is good’ (verblike property term, intransitive predicate)<br />

*Khon níi pen dii<br />

CLF:person PRX ACOP good<br />

‘This person is good’ (verblike property term, intransitive predicate)<br />

PRX = proximate demonstrative<br />

ACOP = attributive copula

Nounlike property concepts behave more like concrete and abstract nouns in<br />

occurring as complement of an attributive copula<br />

Khan níi pen sanǐm<br />

CLF:VEHICLE PRX ACOP rust(y)<br />

‘This vehicle is rusty’ (nounlike property term, copula complement)<br />

*Khan níi sanǐm<br />

CLF:VEHICLE PRX rust(y)<br />

Khon níi pen phará?<br />

CLF:PERSON PRX ACOP monk<br />

‘This man is a monk’ (concrete noun, copula complement)<br />

*Khon níi phará?<br />

CLF:PERSON PRX monk

Verblike property terms take direct verbal predicate negation in mâj ‘NEG’ whereas<br />

nounlike property terms, like nouns, again usually require support of a copula or<br />

other predicative functor.<br />

Ma c’è una costruzione in cui possano occorrere solo i cosiddetti verblike property<br />

terms o i cosiddetti nounlike property terms? Solo in questo caso potremmo<br />

considerarli una classe autonoma…<br />

All and only verblike property terms may uncontroversially occupy the position<br />

provisionally marked “x” in the bare comparative of a discrepancy construction;<br />

stative and active verbs cannot usually occur in this position<br />

[NP1] [X] [COMP] [NP2]

Khon níi sǔuN kwàa khon nân<br />

[CLF:PERSON PRX] NP1 [tall] X [more] COMP [CLF:PERSON DST] NP2<br />

‘This person is taller than that person’ (verblike property term)<br />

*khon níi khít/dəən kwàa khon<br />

[CLF:PERSON PRX] NP1 [think/walk] X [more] COMP [CLF:PERSON<br />

nân<br />

DST] NP2<br />

‘This person thinks/walks more than that person (does)’ (stative/active verbs)<br />

DST = Distal demonstrative<br />

Such distributional differences [can be used] as evidence for<br />

the coalescence of a distinct class of lexemes whose semantic<br />

core is made up of property terms.

Khon níi sǔuN thâw khon nân<br />

[CLF:PERSON PRX] NP1 [tall] X equal [CLF:PERSON DST] NP2<br />

‘This person is tall as that person (is)’ (verblike property term)<br />

*khon níi khít thâw khon nân<br />

[CLF:PERSON PRX] NP1 [think] X equal [CLF:PERSON DST] NP2<br />

‘This person thinks/ as much as that person’ (stative/active verbs)<br />

DST = Distal demonstrative

Una parte del discorso non può essere chiusa: se esiste una classe di <strong>aggettivi</strong>,<br />

deve esistere anche il modo per formare nuovi <strong>aggettivi</strong>.<br />

nâa- “of an entity, have/be of a quality such that it seems like it would be nice to<br />

experience interaction with in terms of VERB”<br />

thanǒn sên nân nâa-dəən kwàa sên níi<br />

road CLF:LINE DST AZR-walk more CLF:LINE PRX<br />

‘That road looks more walkable (better or more suitable to walk on) than this one’<br />

châan- “having the characteristic of doing”<br />

khîi- “having the negative characteristic of doing”

“There is a class of terms in Thai which closely resembles the adjective classes of<br />

many other languages in terms of semantic contents, internal structure, and<br />

distribution relative to other lexical classes, and this class should therefore bear<br />

the label “adjective””<br />

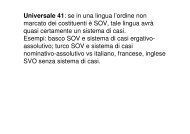

Discovery of a linguistic universal “adjectives, properly defined, requires<br />

establishment of no single necessary and sufficient formal criterion such as<br />

“occurs as copula complement”; what it requires is the discovery that no language<br />

fails to develop grammatical means of treating property concept words differently<br />

from other types of terms. The typological-oriented prediction of Dixon (2004) that<br />

adjectives (so defined) will be found in every language can be falsified through<br />

discovery of a language in which property concept words are in fact NOT treated<br />

in any way differently from another well-defined type of term (say, verb or noun).

Strutture sintattiche e cervello: esistono lingue impossibili?

Area di Broca

“L’ipotesi più probabile è che i limiti delle sintassi delle lingue umane siano dovuti<br />

a una matrice di stampo biologico”<br />

(Andrea Moro (2006), I confini di Babele. Il cervello e il mistero delle lingue<br />

Impossibili, Milano, Bompiani, p. 146)<br />

Perché non ci sono mai (o quasi) errori sintattici?<br />

Perché un bambino può dire, anzi dice io ando o io piangio ma non dice mai casa la?<br />

Esiste una guida biologicamente determinata per l’apprendimento di una lingua,<br />

determinata dall’architettura funzionale del cervello?

1° esperimento: la autonomia della sintassi e il suo ‘posto’ nel cervello<br />

Una lingua immaginaria:<br />

- Hanno disbato le artine<br />

- Molte grapotte amionarono<br />

- Molti celuci furono taffivati<br />

- Nessun cribaso è stato incenghito<br />

…<br />

‘Errori’ fonologici:<br />

- Hanno dinsbato le artine<br />

- Molte grapotrte amionarono<br />

- Mosnti celuci furono taffivati<br />

- Nessun cribaso è stgtato incenghito<br />

…

‘Errori morfosintattici’<br />

- Hanno disbata le artine<br />

- Molti grapotti sono stata amionati<br />

- Molti celuci fu taffivati<br />

- Nessun cribaso siamo incenghito<br />

…<br />

‘Errori’ sintattici<br />

- Hanno disbate artine le con gli ziggoli<br />

- Grapotte molte amionarono<br />

- Celuce delle furono taffivate<br />

- Cribaso è incenghito nessuno a rimbaudo<br />

…<br />

“La nostra speranza […] era di vedere attivare zone diverse a seconda del tipo di<br />

errore e, in defintiva, di vedere per la sintassi una zona diversa dalle altre”<br />

(Andrea Moro (2006), I confini di Babele. Il cervello e il mistero delle lingue<br />

Impossibili, Milano, Bompiani, p. 185)

“Solamente nel caso dell’errore di tipo sintattico si attivano alcune zone sottocorticali<br />

dell’encefalo insieme alla componente profonda dell’area di Broca […].<br />

Questo è il punto centrale. Il riconoscimento dell’errore di tipo sintattico coinvolge una<br />

rete complessa che non si riscontra negli altri tipi di errori e tale rete non è<br />

rappresentata in un’unica area corticale ma si presenta come un insieme integrato di<br />

zone diverse”<br />

(Andrea Moro (2006), I confini di Babele. Il cervello e il mistero delle lingue<br />

Impossibili, Milano, Bompiani, p. 189)<br />

“Non solo dunque non esiste un’area singola per il linguaggio […], ma non esiste<br />

nemmeno un’area singola per la sintassi!”<br />

(Andrea Moro (2006), I confini di Babele. Il cervello e il mistero delle lingue<br />

Impossibili, Milano, Bompiani, p. 190)

2° esperimento: “far apprendere a dei soggetti adulti delle lingue straniere,<br />

«nascondendo», tra le regole delle grammatiche che i soggetti si apprestavano<br />

a imparare, delle regole che violano la grammatica universale, più specificamente<br />

delle regole che violano la dipendenza dalla struttura”<br />

(Andrea Moro (2006), I confini di Babele. Il cervello e il mistero delle lingue<br />

Impossibili, Milano, Bompiani, p. 195)<br />

(Andrea Moro (2006), I confini di Babele.<br />

Il cervello e il mistero delle lingue<br />

Impossibili, Milano, Bompiani, p. 203)

- Dipendenza dalla struttura<br />

Es. La ragazza di Pietro suona bene il pianoforte<br />

*Il Pietro pianoforte bene di ragazza suona la<br />

*Il pianoforte di Pietro suona bene la ragazza<br />

*il gatto si nascondono dietro l’albero<br />

I bambini che hanno inseguito il gatto si nascondono<br />

dietro l’albero

“Il fatto di rispettare o meno la dipendenza strutturale è dunque irrilevante per quanto<br />

riguarda l’accuratezza dell’apprendimento: sia che si trattasse si regole possibili, sia<br />

che si trattasse di regole impossibili, i soggetti arrivavano a una padronanza del tutto<br />

comparabile”<br />

(Andrea Moro (2006), I confini di Babele. Il cervello e il mistero delle lingue<br />

Impossibili, Milano, Bompiani, p. 205)<br />

Non ci sono lingue che non si possono imparare!<br />

Ma ci sono lingue che, naturalmente, non si sviluppano mai,<br />

anche se, appunto, saremmo in grado di apprenderle o usarle…

“Al crescere dell’accuratezza delle risposte sui giudizi di grammaticalità […]<br />

l’attività dell’area di Broca […] aumenta per le regole possibili mentre diminuisce<br />

per quelle impossibili. Il cervello ha, per così dire, «smistato» i dati sintattici (<strong>senza</strong><br />

che i soggettine avessero coscienza) e ha fatto elaborare solo le frasi che preservano<br />

la dipendenza dalla struttura dall’area normalmente predisposta per i compiti sintattici<br />

(l’area di Broca); nell’elaborazione di frasi che non rispettano la dipendenza dalla<br />

struttura, invece, l’attività nella stessa area diminuisce progressivamente”<br />

(Andrea Moro (2006), I confini di Babele. Il cervello e il mistero delle lingue<br />

Impossibili, Milano, Bompiani, p. 205)

Perceiving and naming actions and objects<br />

M. Liljeström, A. Tarkiainen, T. Parviainen, J. Kujala, J. Numminen, J. Hiltunen,<br />

M. Laine, and R. Salmelina<br />

NeuroImage 41 (2008) 1132–1141<br />

The existence of patients in whom focal brain damage is combined with<br />

selective impairments of grammatical categories has led to the suggestion that<br />

there are distinct cortical areas for processing verbs and nouns<br />

Lesion data has implied a link between left frontal areas and verb<br />

processing, whereas noun processing seems to depend on the integrity of<br />

left temporal areas

Nouns and verbs are distinguished in the brain on the basis of their semantic<br />

properties, nouns typically referring to objects and verbs to actions.<br />

In the present fMRI experiment, healthy subjects were asked to silently name<br />

actions and objects that were presented as simple line drawings. We used two<br />

sets of pictures, one depicting actions performed on/with objects and the other<br />

displaying only the objects. Subjects named both actions and objects from the<br />

action images, and objects from the object images. Actions were not named<br />

from pictures with isolated objects, as this task would require the subject to<br />

make inferences about the actions, a process not required in object naming. This<br />

design addresses the following questions:<br />

(i) Do action and object naming activate different cortical regions when the<br />

stimulus is identical?<br />

(ii) How does the content of the image (with/without action) modulate the brain<br />

correlates of object naming?

The task was to silently name actions or objects from simple line drawings.<br />

Two sets of images were used, each with 100 scenes. Action images illustrated<br />

a simple event (e.g. to write with a pen) whereas object-only images consisted<br />

of objects from the same images when the action had been dissolved into<br />

arbitrary lines in the background, in order to keep the visual complexity of<br />

the image unchanged.<br />

The corresponding object and action words were mostly of medium to high<br />

frequency in the Finnish language.<br />

The verb and noun corresponding to one image always had different word<br />

stems.

The experiment consisted of three conditions:<br />

(i) action naming from action images (Act),<br />

(ii) object naming from action images (ObjAct),<br />

(iii) object naming from object-only images (Obj).<br />

Task periods (30 s) and rest periods (21 s) alternated in a block design. There<br />

were two sessions, each lasting about 13 min.<br />

In order to avoid movement artifacts the participants were instructed to name the<br />

actions or objects silently. Subjects were asked to keep their eyes straight ahead<br />

during the rest condition and not to move during the experiment.<br />

Results: A similar <strong>net</strong>work of cortical areas was activated in all three conditions,<br />

including bilateral occipitotemporal and parietal regions, and left frontal cortex.

The occipitotemporal cortex and the fusiform gyrus were activated bilaterally in all<br />

conditions. When actions or objects were named from action images (Act and<br />

ObjAct) the activation additionally encompassed the left posterior middle<br />

temporal cortex. Activation was seen in the left inferior frontal gyrus in all tasks. In<br />

both action and object naming from action images (Act and ObjAct) the activation<br />

centered in the operculum of the inferior frontal gyrus and extended superiorly to<br />

include the precentral gyrus and anteriorly to BA 47. The frontal activation was<br />

less pronounced when objects were named from object-only images (Obj), mainly<br />

encompassing the inferior frontal region.

Naming objects from the images with action context compared to naming the same<br />

objects from object-only images (ObjActNObj, Fig. 3B) resulted in significantly<br />

stronger activation in a large mostly left-lateralized <strong>net</strong>work, including the precentral<br />

gyrus (BA 6/9), the inferior frontal gyrus (pars opercularis and triangularis), the<br />

inferior and superior parietal lobules (BA 7/40), and the posterior middle temporal<br />

gyrus. Naming actions compared to naming objects from object-only images<br />

(ActNObj, Fig. 3C) revealed enhanced activation in the left supramarginal gyrus<br />

(parieto-temporal junction; BA 40), left and right posterior middle temporal cortex,<br />

left precentral gyrus and superior medial frontal gyrus.<br />

Our results indicate that action and object naming engage a common cortical<br />

<strong>net</strong>work, but that the provided input (action pictures, object-only pictures) and the<br />

requested output (verb, noun) influence the level of activation in a subset of areas<br />

within that <strong>net</strong>work.<br />

The stronger activation in naming objects from pictures with action context,<br />

relative both to naming actions from the same images and to naming objects<br />

from object-only pictures, suggests involvement of additional task-specific<br />

processes.

We found no regions specific to nouns as a grammatical category. Our results<br />

agree with a recent study showing that when naming events either as verbs or<br />

nouns from identical images, no differences were found between verbs or nouns<br />

as grammatical categories.<br />

Our results converge with previous evidence showing that retrieval of verbs and<br />

nouns in the healthy human brain using identical stimuli in a picture naming task<br />

engages a similar distributed cortical <strong>net</strong>work, as measured with BOLD fMRI.<br />

Importantly, however, the content of the image (action vs. object only) had a<br />

pronounced effect on the activation in parts of that <strong>net</strong>work that have previously<br />

been implicated in processing of action knowledge. Furthermore, object naming in<br />

the context of action revealed additional activations, both in comparison to verb<br />

retrieval from the same set of images, and in comparison to noun retrieval from<br />

images not depicting action, suggesting that attention may be more directed<br />

towards motor-based properties of objects when they are presented not as single<br />

entities but as part of images that also depict the relevant action.