How many gamergates is an ant queen worth? - ResearchGate

How many gamergates is an ant queen worth? - ResearchGate

How many gamergates is an ant queen worth? - ResearchGate

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften (2008) 95:109–116<br />

DOI 10.1007/s00114-007-0297-0<br />

ORIGINAL PAPER<br />

<strong>How</strong> <strong>m<strong>an</strong>y</strong> <strong>gamergates</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>t <strong>queen</strong> <strong>worth</strong>?<br />

Thibaud Monnin & Chr<strong>is</strong>ti<strong>an</strong> Peeters<br />

Received: 13 September 2006 /Rev<strong>is</strong>ed: 14 May 2007 /Accepted: 2 August 2007 / Publ<strong>is</strong>hed online: 25 August 2007<br />

# Springer-Verlag 2007<br />

Abstract Ant reproductives exhibit different morphological<br />

adaptations linked to d<strong>is</strong>persal <strong>an</strong>d fertility. By reviewing<br />

the literature on taxa where workers c<strong>an</strong> reproduce<br />

sexually (i.e. become <strong>gamergates</strong>) we show that (1) species<br />

with a single gamergate generally have lost the winged<br />

<strong>queen</strong> caste, whereas only half of the species with several<br />

<strong>gamergates</strong> have, <strong>an</strong>d (2) single-gamergate species have<br />

smaller colonies th<strong>an</strong> multiple-gamergate species. Compar<strong>is</strong>on<br />

with “classical” <strong>an</strong>ts without <strong>gamergates</strong>, where<br />

having one vs having several winged <strong>queen</strong>s are two<br />

d<strong>is</strong>tinct syndromes, suggests that having one vs having<br />

several <strong>gamergates</strong> are not. Gamergate number does not<br />

affect the success of colony f<strong>is</strong>sion, but retention of the<br />

<strong>queen</strong> caste permits the option of independent foundation.<br />

Keywords Queenless <strong>an</strong>ts . Monogyny. Polygyny.<br />

Colony size . D<strong>is</strong>persal . F<strong>is</strong>sion<br />

Introduction<br />

Colony-founding strategies of <strong>an</strong>ts are largely shaped by<br />

selective pressures on the survival <strong>an</strong>d d<strong>is</strong>persal of sexuals<br />

(e.g. Bourke <strong>an</strong>d Fr<strong>an</strong>ks 1995; Peeters <strong>an</strong>d Ito 2001). At<br />

one extreme, species favour d<strong>is</strong>persal <strong>an</strong>d produce <strong>m<strong>an</strong>y</strong><br />

winged <strong>queen</strong>s that fly away from the colony to mate <strong>an</strong>d<br />

start new colonies alone. Th<strong>is</strong> strategy of independent colony<br />

foundation <strong>is</strong> character<strong>is</strong>ed by the production of <strong>m<strong>an</strong>y</strong><br />

T. Monnin (*) : C. Peeters<br />

Fonctionnement et évolution des systèmes écologiques<br />

CNRS UMR 7625, Université Pierre et Marie Curie,<br />

7 quai Saint Bernard,<br />

75005 Par<strong>is</strong>, Fr<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

e-mail: Thibaud.Monnin@snv.jussieu.fr<br />

C. Peeters<br />

e-mail: cpeeters@snv.jussieu.fr<br />

reproductives with high d<strong>is</strong>persal but low success. In contrast,<br />

other species produce few <strong>queen</strong>s d<strong>is</strong>persing on foot<br />

accomp<strong>an</strong>ied by <strong>m<strong>an</strong>y</strong> workers. Th<strong>is</strong> strategy of colony<br />

f<strong>is</strong>sion (also termed budding) <strong>is</strong> character<strong>is</strong>ed by the production<br />

of few reproductive propagules [<strong>queen</strong>(s) <strong>an</strong>d accomp<strong>an</strong>ying<br />

workers] with low d<strong>is</strong>persal but high success.<br />

Some species mix both strategies by producing <strong>queen</strong>s<br />

d<strong>is</strong>persing alone on the wing as well as reproductives d<strong>is</strong>persing<br />

on foot with workers (e.g. Peeters 1997; Heinze <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Keller 2000; Peeters <strong>an</strong>d Ito 2001). Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> the case of some<br />

<strong>an</strong>ts where the workers are capable of mating <strong>an</strong>d sexual<br />

reproduction. Some of these species have lost the <strong>queen</strong><br />

caste <strong>an</strong>d exclusively reproduce by colony f<strong>is</strong>sion, with one<br />

or more mated workers (called <strong>gamergates</strong>, Peeters <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Crewe 1984) establ<strong>is</strong>hing new colonies with the help of<br />

nestmate workers. <strong>How</strong>ever, others have retained the <strong>queen</strong><br />

caste <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>an</strong> thus reproduce by both independent colony<br />

foundation <strong>an</strong>d colony f<strong>is</strong>sion.<br />

Species with <strong>gamergates</strong> are restricted to three subfamilies<br />

characterized by a low degree of dimorph<strong>is</strong>m between<br />

winged <strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d workers (Amblyoponinae, Ectatomminae,<br />

Ponerinae). We review the literature <strong>an</strong>d investigate<br />

the relationships between occurrence of the <strong>queen</strong> caste,<br />

gamergate number <strong>an</strong>d colony size. We d<strong>is</strong>cuss th<strong>is</strong> in<br />

the light of the evolution of multiple-breeders societies<br />

<strong>an</strong>d the tr<strong>an</strong>sition from independent colony foundation to<br />

colony f<strong>is</strong>sion, <strong>an</strong>d we draw compar<strong>is</strong>ons with the monogynous<br />

<strong>an</strong>d polygynous “syndromes” often used to categor<strong>is</strong>e<br />

“classical” <strong>an</strong>ts with winged <strong>queen</strong>s (reviewed in e.g.<br />

Bourke <strong>an</strong>d Fr<strong>an</strong>ks 1995).<br />

Materials <strong>an</strong>d methods<br />

Although <strong>gamergates</strong> were first described in species that<br />

lack a <strong>queen</strong> caste, hence the now familiar “<strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>t”

110 Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften (2008) 95:109–116<br />

label, <strong>gamergates</strong> also occur in some species that have<br />

retained winged <strong>queen</strong>s. In the present paper, “<strong>queen</strong>less”<br />

refers to species that always lack the <strong>queen</strong> caste, <strong>an</strong>d we<br />

explicitly state when we refer to species that have both<br />

<strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d <strong>gamergates</strong>.<br />

We compare single- vs multiple-gamergate species for the<br />

occurrence of <strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d colony size. Thirty-five species<br />

(11 genera) for which 6 to 129 colonies were collected are<br />

included in our <strong>an</strong>alys<strong>is</strong>. Eleven species with five or less<br />

colonies collected are excluded because gamergate number<br />

<strong>an</strong>d colony size c<strong>an</strong>not be determined reliably. We c<strong>an</strong>not<br />

control for phylogenetic relationships because there are no<br />

species-level phylogenies in the genera investigated. We limit,<br />

to some extent, the potential problems of non-independence<br />

of species by working at the genus level in addition to species<br />

level. To do th<strong>is</strong>, we pool congeneric species with one vs<br />

several <strong>gamergates</strong> <strong>an</strong>d compare genera for the occurrence of<br />

the <strong>queen</strong> caste <strong>an</strong>d colony size. Working at the genus level<br />

<strong>is</strong> justified because each genus where <strong>gamergates</strong> occur represents<br />

at least one independent evolution of <strong>gamergates</strong>.<br />

Indeed, all the genera with <strong>gamergates</strong> included in recent<br />

molecular phylogenies are more related to one or several<br />

genera without <strong>gamergates</strong> th<strong>an</strong> to <strong>an</strong>other genus with <strong>gamergates</strong><br />

(Moreau et al. 2006; Brady et al. 2006). For inst<strong>an</strong>ce,<br />

Rhytidoponera <strong>an</strong>d Gnamptogenys (with <strong>gamergates</strong>) are<br />

more closely related to Ectatomma <strong>an</strong>d Typhlomyrmex (without<br />

<strong>gamergates</strong>), respectively, th<strong>an</strong> to each other. Additionally,<br />

8 of the 11 genera with <strong>gamergates</strong> include “classical”<br />

species with <strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d no <strong>gamergates</strong>. The hypothes<strong>is</strong> that<br />

<strong>gamergates</strong> evolved independently within each of these<br />

genera <strong>is</strong> more parsimonious th<strong>an</strong> the hypothes<strong>is</strong> of evolution<br />

in a common <strong>an</strong>cestor. Only two genera (Pachycondyla <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Platythyrea) include both single- <strong>an</strong>d multiple-gamergate<br />

species, <strong>an</strong>d both also have “classical” species with <strong>queen</strong>s<br />

<strong>an</strong>d no <strong>gamergates</strong>. For these genera, we pooled species<br />

according to gamergate number (either single-gamergate or<br />

multiple-gamergate species).<br />

Our genus-level approach <strong>is</strong> validated by recent molecular<br />

phylogenies that have establ<strong>is</strong>hed the monophyly of<br />

currently recognized genera in subfamilies Ponerinae <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Ectatomminae (Brady et al. 2006; Moreau et al. 2006). A<br />

notable exception <strong>is</strong> Pachycondyla in which several genera<br />

have been synonymized (Bolton 2003). We take a conservative<br />

approach <strong>an</strong>d consider Pachycondyla as one unit,<br />

although <strong>gamergates</strong> may have evolved repeatedly in its<br />

constituent taxa. In contrast, we consider Dinoponera <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Streblognathus as unrelated because new molecular data<br />

show that they are not s<strong>is</strong>ter genera (J. Schmidt, personal<br />

communication), unlike previously thought.<br />

We define colony size as the number of workers plus<br />

dealated <strong>queen</strong>s (i.e. <strong>queen</strong>s who shed their wings), irrespective<br />

of whether these <strong>queen</strong>s were mated <strong>an</strong>d laying eggs or<br />

not, thereby excluding winged gynes (young virgin <strong>queen</strong>s)<br />

<strong>an</strong>d males. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> because dealated <strong>queen</strong>s will stay in the<br />

colony, whereas alate <strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d males will leave. For species<br />

where some colonies have <strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d others have <strong>gamergates</strong>,<br />

average colony size <strong>is</strong> given for both types of colonies, but all<br />

colonies were pooled for inter-specific compar<strong>is</strong>ons.<br />

Results<br />

Gamergate number <strong>an</strong>d occurrence of the <strong>queen</strong> caste<br />

Gamergate number strongly correlates with the presence<br />

of <strong>queen</strong>s. All single-gamergate species in our sample<br />

lack <strong>queen</strong>s (n=19, Table 1), whereas 8 of 16 multiplegamergate<br />

species have <strong>queen</strong>s (Table 2, Yates’ corrected<br />

χ 2 =9.64, df=1, p=0.0019). Th<strong>is</strong> difference remains true<br />

when pooling species by genus: none of the six genera with<br />

single-gamergate species has species with both <strong>gamergates</strong><br />

<strong>an</strong>d <strong>queen</strong>s, whereas five of the seven genera with multiplegamergate<br />

species have (Tables 1 <strong>an</strong>d 2, Yates’ corrected<br />

χ 2 =4.27, df=1, p=0.0387). Import<strong>an</strong>tly, <strong>queen</strong>s are unknown<br />

in Diacamma, Dinoponera <strong>an</strong>d Streblognathus, three<br />

genera where all species have a single gamergate, whereas<br />

<strong>queen</strong>s ex<strong>is</strong>t in various species belonging to the other genera<br />

with <strong>gamergates</strong>.<br />

Multiple-gamergate species form a heterogeneous group <strong>an</strong>d<br />

no pattern emerges regarding the occurrence of <strong>queen</strong>s<br />

(Table 2). The numbers of <strong>gamergates</strong> <strong>an</strong>d <strong>queen</strong>s vary<br />

widely, <strong>an</strong>d either caste of female c<strong>an</strong> dominate reproduction.<br />

Several species have colonies with multiple <strong>gamergates</strong> <strong>an</strong>d/or<br />

asingle<strong>queen</strong>(n=7), <strong>an</strong>d one has multiple <strong>gamergates</strong> or<br />

several functional <strong>queen</strong>s (Gnamptogenys striatula). Queens<br />

<strong>an</strong>d <strong>gamergates</strong> c<strong>an</strong> cohabit in the same colonies in three<br />

species, namely, Pachycondyla (Bothroponera) tridentata<br />

(Sommer <strong>an</strong>d Hölldobler 1992; Sommer et al. 1994), Platythyrea<br />

quadridenta (Ito 1994) <strong>an</strong>dPlatythyrea sp.1(F.Ito,<br />

personal communication). In P. tridentata <strong>an</strong>d P. quadridenta,<br />

some dealated <strong>queen</strong>s do not lay eggs, <strong>an</strong>d in<br />

P. tridentata th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> because <strong>queen</strong>s c<strong>an</strong> be behaviourally<br />

dominated by <strong>gamergates</strong> <strong>an</strong>d consequently suppressed<br />

from reproducing. Queens <strong>an</strong>d <strong>gamergates</strong> never occur<br />

simult<strong>an</strong>eously in the other five species. In Harpegnathos<br />

saltator, <strong>queen</strong>s found new colonies independently after a<br />

nuptial flight, <strong>an</strong>d some of their daughter workers mate<br />

<strong>an</strong>d reproduce after their death. Unlike other <strong>an</strong>ts with<br />

<strong>gamergates</strong>, colonies do not propagate by f<strong>is</strong>sion, but<br />

<strong>queen</strong>s perform independent colony foundation, with<br />

colonies headed by <strong>gamergates</strong> producing new <strong>queen</strong>s<br />

<strong>an</strong>nually. Thus each colony goes through a <strong>queen</strong> phase<br />

followed by a gamergate phase (Peeters <strong>an</strong>d Hölldobler<br />

1995; Peetersetal.2000). In Gnamptogenys menadens<strong>is</strong>,<br />

colonies founded by a <strong>queen</strong> also become headed by<br />

<strong>gamergates</strong> after the death of the <strong>queen</strong>. <strong>How</strong>ever, unlike in

Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften (2008) 95:109–116 111<br />

Table 1 Average colony size of single-gamergate species<br />

Species Colony size me<strong>an</strong>±SD<br />

(r<strong>an</strong>ge)<br />

H. saltator, most colonies are produced by f<strong>is</strong>sion <strong>an</strong>d do not<br />

go through a <strong>queen</strong> phase. Indeed, only 5% of colonies are<br />

headed by a <strong>queen</strong> (Gobin et al. 1998). Th<strong>is</strong> contrasts with<br />

G. striatula where 96% of colonies have <strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d no<br />

<strong>gamergates</strong>. Th<strong>is</strong> species has numerous <strong>queen</strong>s (14±18,<br />

me<strong>an</strong>±SD) so that it <strong>is</strong> unlikely that a colony ever loses all<br />

of them. <strong>How</strong>ever, workers start to perform sexual calling in<br />

experimentally orph<strong>an</strong>ed colonies (Blatrix <strong>an</strong>d Ja<strong>is</strong>son 2000),<br />

<strong>an</strong>d in one population <strong>gamergates</strong> reproduced in two<br />

colonies lacking <strong>queen</strong>s (Blatrix 2000; Blatrix <strong>an</strong>d Ja<strong>is</strong>son<br />

2000). In Rhytidoponera chalybea <strong>an</strong>d Rhytidoponera confusa,<br />

workers also differentiate into <strong>gamergates</strong> after <strong>queen</strong><br />

death (Ward 1983, C. Peeters, unpubl<strong>is</strong>hed data). Last,<br />

Rhytidoponera metallica occasionally produce <strong>queen</strong>s. These<br />

are capable of starting colonies in the laboratory (Ward<br />

1986), but they have never been found to head colonies in<br />

nature, suggesting that th<strong>is</strong> species <strong>is</strong> in the process of losing<br />

the <strong>queen</strong> caste.<br />

Gamergate number <strong>an</strong>d colony size<br />

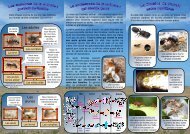

Our considerably exp<strong>an</strong>ded sample of species confirms<br />

Peeters’ (1993) remark that single-gamergate species have<br />

Excavated<br />

colonies<br />

smaller colonies th<strong>an</strong> multiple-gamergate species, with 83±<br />

83 workers in the former vs 169±154 in the latter (me<strong>an</strong>±<br />

SD, single-gamergate species: n=19, medi<strong>an</strong>=54, quartiles=<br />

15 <strong>an</strong>d 124, Table 1; multiple-gamergate species: n=16,<br />

medi<strong>an</strong>=136, quartiles=41 <strong>an</strong>d 237, Table 2; colonysizes<br />

are not normally d<strong>is</strong>tributed <strong>an</strong>d were tr<strong>an</strong>sformed in square<br />

roots, which are normally d<strong>is</strong>tributed <strong>an</strong>d show homogeneity<br />

of vari<strong>an</strong>ce; t test for independent samples: t=−2.069,<br />

df=33, p=0.046, Fig. 1a). Pooling species by genus shows<br />

the same trend, albeit not stat<strong>is</strong>tically signific<strong>an</strong>t (Fig. 1b):<br />

genera with single-gamergate species have colonies of 64±61<br />

workers, whereas genera with multiple-gamergate species<br />

have colonies of 133±107 workers (single-gamergate genera:<br />

n=6, medi<strong>an</strong>=56, quartiles=23 <strong>an</strong>d 68, Table 3; multiplegamergate<br />

genera: n=7, medi<strong>an</strong>=102, quartiles=65 <strong>an</strong>d 251,<br />

Table 3; M<strong>an</strong>n–Whitney U: z=−1.500, p=0.134).<br />

D<strong>is</strong>cussion<br />

References<br />

Diacamma australe 129±56 9 Peeters <strong>an</strong>d Higashi 1989<br />

Diacamma ceylonense “nilgiri” 267±109 10 Cournault <strong>an</strong>d Peeters, submitted for publication<br />

Diacamma cy<strong>an</strong>eiventre 214±80 6 André et al. 2001<br />

Diacamma ceylonense 247 (91–499) 39 Cuvillier-Hot et al. 2001, Karpakakunjaram et al. 2003<br />

Diacamma sp. from Jap<strong>an</strong> 124±50 29 Fukumoto et al. 1989, Kawabata <strong>an</strong>d Tsuji 2005<br />

Diacamma sp. from Malaysia 86±41 51 Sommer et al. 1993<br />

Dinoponera austral<strong>is</strong> 15±7 66 Fowler 1985, Paiva <strong>an</strong>d Br<strong>an</strong>dão 1995, Paiva 1997,<br />

Monnin, unpubl<strong>is</strong>hed data<br />

Dinoponera gig<strong>an</strong>tea 54±27 10 Overal 1980, Fourcassié <strong>an</strong>d Oliveira 2002, Monnin,<br />

unpubl<strong>is</strong>hed data<br />

Dinoponera quadriceps 73±39 70 Monnin <strong>an</strong>d Peeters 1999, Monnin, unpubl<strong>is</strong>hed data,<br />

Vasconcellos et al. 2004<br />

Pachycondyla (crassa-group) krugeri 45±22 19 Peeters <strong>an</strong>d Crewe 1986, Wildm<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d Crewe 1988, Villet<br />

<strong>an</strong>d Wildm<strong>an</strong> 1991<br />

Pachycondyla (Hagensia) havil<strong>an</strong>di 25±9 13 Villet 1992<br />

Pachycondyla (Bothroponera) sp.<br />

8 from West Java<br />

11±6 8 Ito 1993a<br />

Pachycondyla (Bothroponera) 9(2–18) 53 Peeters et al. 1991, Ito <strong>an</strong>d Higashi 1991, Higashi et al.<br />

sublaev<strong>is</strong><br />

1994<br />

Platythyrea lamellosa 115±83 25 Villet et al. 1990<br />

Platythyrea schultzei 21±10 7 Villet 1991<br />

Streblognathus aethiopicus 35 (9–51) 24 Ware et al. 1990, Cuvillier-Hot 2002<br />

Streblognathus peetersi 95±45 44 Cuvillier-Hot 2002<br />

Thaumatomyrmex atrox 4(1–9) 52 Jahyny et al. 2002<br />

Thaumatomyrmex contumax 2.5 (1–9) 8 Jahyny et al. 2002<br />

When several studies were pooled the SD could only be calculated when the authors provided the raw data. Otherw<strong>is</strong>e, the r<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>is</strong> given<br />

(minimum–maximum). All the species belong to the subfamily Ponerinae (Bolton 2003).<br />

Our review reveals two clear patterns: single-gamergate<br />

species mostly lack <strong>queen</strong>s (a few exceptions ex<strong>is</strong>t; F. Ito,<br />

personal communication), whereas multiple-gamergate spe-

112 Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften (2008) 95:109–116<br />

Table 2 Average colony size <strong>an</strong>d occurrence of the <strong>queen</strong> caste in multiple-gamergate species<br />

Species Colonies with <strong>gamergates</strong> only Colonies with <strong>queen</strong>(s) References<br />

Excavated<br />

colonies<br />

Colony<br />

size<br />

Gamergate<br />

number<br />

Queen<br />

number<br />

Colony size Excavated<br />

colonies<br />

Gamergate<br />

number<br />

Amblyopone reclinata 6±5 102±50 22 Ito 1993b<br />

Gnamptogenys menadens<strong>is</strong> 5±4 111±77 35 1 0 141±43 2 Gobin et al. 1998<br />

Gnamptogenys striatula 25/565 <strong>an</strong>d 445±226 2 14±18<br />

31/266<br />

a<br />

0 386±313 47 Blatrix 2000, Blatrix <strong>an</strong>d Ja<strong>is</strong>son<br />

2000<br />

Harpegnathos saltator b<br />

3 to 6 83±58 16 1 0 58±30 43 Peeters et al. 2000<br />

Leptogenys peuqueti 4±4 30±24 13 Ito 1997<br />

Leptogenys schwabi 6/260 <strong>an</strong>d 184±76 17 Davies et al. 1994<br />

7/146<br />

Leptogenys sp. 24 3±4 13±7 8 Ito 1997<br />

Pachycondyla (Ophthalmopone) 13±16 158±160 37 Peeters <strong>an</strong>d Crewe 1984, 1985, 1986,<br />

berthoudi<br />

Sledge et al. 1996, 1999, 2001<br />

Pachycondyla (Bothroponera) 81 to 100% 42±16 3 1<br />

tridentata<br />

c<br />

86 to 100% 58±28 4 Sommer et al. 1994<br />

Platythyrea quadridenta 2±2 18±15 14 1 d<br />

2±3 31±30 2 Ito 1994, personal communication<br />

Platythyrea sp.1 3±2 17±6 10 1 4±2 19±3 3 F. Ito, personal communication<br />

Rhytidoponera aurata e<br />

22±9 182±98 13 Komene et al. 1999<br />

Rhytidoponera chalybea f<br />

4±3.5 181±154 48 1 0 440±171 21 Ward 1983<br />

Rhytidoponera confusa f<br />

4±3.5 164±208 64 1 0 264±144 65 Ward 1983<br />

Rhytidoponera metallica 5 to 15% 381 (79–1,092) 16 Chapu<strong>is</strong>at <strong>an</strong>d Crozier 2001, Thomas<br />

<strong>an</strong>d Elgar 2003<br />

Rhytidoponera mayri (sp. 12) 20±19 528±269 12 Pamilo et al. 1985, Peeters 1987, Tay<br />

<strong>an</strong>d Crozier 2000<br />

Gamergate number, colony size <strong>an</strong>d dealated <strong>queen</strong> number are given as me<strong>an</strong>±SD (r<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>is</strong> given when SD could not be determined). The fraction of <strong>gamergates</strong> (e.g. 25 <strong>gamergates</strong> out of 565<br />

workers in G. striatula) <strong>is</strong> given when only few colonies were d<strong>is</strong>sected or when colonies were not d<strong>is</strong>sected in their entirety. Gnamptogenys <strong>an</strong>d Rhytidoponera belong to the subfamily<br />

Ectatomminae, Amblyopone belongs to Amblyoponinae, <strong>an</strong>d the other genera belong to Ponerinae (Bolton 2003).<br />

a<br />

Alate <strong>queen</strong>s were included because <strong>m<strong>an</strong>y</strong> were mated <strong>an</strong>d laying eggs. Most <strong>queen</strong>s reproduce; 66±41% of 100 <strong>queen</strong>s from 18 colonies were mated <strong>an</strong>d laying eggs (84±29% for dealate<br />

<strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d 43±44% for alate <strong>queen</strong>s, Blatrix 2000).<br />

b<br />

The population from B<strong>an</strong>galore <strong>is</strong> atypical (Peeters et al. 2000) <strong>an</strong>d therefore excluded from these data.<br />

c<br />

Only 1 out of 5±9 dealated <strong>queen</strong>s (47% of which were inseminated) had developed ovaries <strong>an</strong>d laid eggs in one colony, simult<strong>an</strong>eously with several <strong>gamergates</strong> (Sommer et al. 1994).<br />

d<br />

Th<strong>is</strong> colony contained a second dealated but non-laying <strong>queen</strong> (Ito 1994).<br />

e<br />

In R. aurata, 11 additional colonies were found to have only one gamergate <strong>an</strong>d to be smaller, with only 75±38 workers (Komene et al. 1999). Th<strong>is</strong> bimodal d<strong>is</strong>tribution differs from other<br />

multiple-gamergate species, where gamergate number varies continuously, <strong>an</strong>d Komene et al. (1999) suggest that these small monogynous colonies are new colonies founded by f<strong>is</strong>sion.<br />

f<br />

Ward (1983) gives the average gamergate number for R. chalybea <strong>an</strong>d R. confusa colonies pooled together but not for each species.

Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften (2008) 95:109–116 113<br />

Colony size<br />

a species level b genus level<br />

250<br />

200<br />

150<br />

100<br />

50<br />

0<br />

Single Multiple<br />

cies often retain them, <strong>an</strong>d the former species have smaller<br />

colonies th<strong>an</strong> the latter. These patterns are also true at the<br />

genus level. We estimate that ca. 200–300 species of <strong>an</strong>ts<br />

have <strong>gamergates</strong>, <strong>an</strong>d thus future studies will enrich th<strong>is</strong><br />

comparative approach.<br />

Gamergates c<strong>an</strong>not found new colonies independently,<br />

for both proximate (e.g. no metabolic reserves) <strong>an</strong>d ultimate<br />

Table 3 Colony size at the genus level, calculated by averaging the<br />

me<strong>an</strong> colony size of the species of the given genus<br />

Genera Colony<br />

size<br />

350<br />

300<br />

250<br />

200<br />

150<br />

100<br />

Number of<br />

species<br />

Single Multiple<br />

Gamergate number<br />

Fig. 1 Colony size of single- <strong>an</strong>d multiple-gamergate species <strong>an</strong>d<br />

genus. a Colony size at the species level. The graph shows the backtr<strong>an</strong>sformed<br />

me<strong>an</strong>s±95% confidence intervals of the squared root<br />

data. Single-gamergate species have smaller colonies th<strong>an</strong> multiplegamergate<br />

species. b Colony size at the genus level. Box plots give<br />

medi<strong>an</strong>, quartiles <strong>an</strong>d r<strong>an</strong>ge. Single-gamergate genera tend to have<br />

smaller colonies th<strong>an</strong> multiple-gamergate genera, but the difference <strong>is</strong><br />

not signific<strong>an</strong>t. See results for stat<strong>is</strong>tics<br />

Single gamergate<br />

Diacamma 178 6 144<br />

Dinoponera 47 3 146<br />

Pachycondyla 23 4 93<br />

Platythyrea 68 2 32<br />

Streblognathus 65 2 68<br />

Thaumatomyrmex 3 2 60<br />

Multiple <strong>gamergates</strong><br />

Amblyopone 102 1 22<br />

Gnamptogenys 251 2 86<br />

Harpegnathos 65 1 59<br />

Leptogenys 76 3 38<br />

Pachycondyla 105 2 44<br />

Platythyrea 19 2 29<br />

Rhytidoponera 313 5 239<br />

Excavated<br />

colonies<br />

Pachycondyla <strong>is</strong> the only genus with both single- <strong>an</strong>d multiplegamergate<br />

species, <strong>an</strong>d th<strong>is</strong> reflects its polyphyletic status<br />

50<br />

0<br />

(fitness adv<strong>an</strong>tages of staying in natal colony, given limited<br />

d<strong>is</strong>persal on ground) reasons (Liebig et al. 1998). Accordingly,<br />

colony f<strong>is</strong>sion <strong>is</strong> obligate in gamergate species without<br />

winged <strong>queen</strong>s. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> true regardless of gamergate<br />

number which has no known impact on the success of f<strong>is</strong>sion.<br />

Therefore, with respect to colony d<strong>is</strong>persal, having<br />

one vs several <strong>gamergates</strong> may not be two d<strong>is</strong>tinct strategies<br />

<strong>an</strong>alogous to having one vs several <strong>queen</strong>s in<br />

“classical” <strong>an</strong>ts. Indeed, in the latter, the tr<strong>an</strong>sition from<br />

monogyny to polygyny <strong>is</strong> often associated with a tr<strong>an</strong>sition<br />

from independent colony foundation to colony f<strong>is</strong>sion (e.g.<br />

Solenops<strong>is</strong> invicta, Ross <strong>an</strong>d Keller 1995; Myrmica rubra,<br />

Walin et al. 2001; Formica, Sundström et al. 2005). Bourke<br />

<strong>an</strong>d Fr<strong>an</strong>ks (1995) reviewed various factors that favour the<br />

evolution of multiple-<strong>queen</strong> societies, such as high predation<br />

on <strong>queen</strong>s during mating <strong>an</strong>d nest initiation, habitat<br />

patchiness (d<strong>is</strong>persing <strong>queen</strong>s may fail to find a suitable<br />

habitat) <strong>an</strong>d nest site limitation. Clearly, these factors also<br />

favour a shift from independent colony foundation to f<strong>is</strong>sion.<br />

Habitat saturation (i.e. incipient colonies may be<br />

outcompeted) favours large multiple-<strong>queen</strong> colonies reproducing<br />

by colony f<strong>is</strong>sion (e.g. Crozier <strong>an</strong>d Pamilo 1996;<br />

Tschinkel 2006). Nonetheless, gamergate number affects<br />

nestmate relatedness, so that having one vs several <strong>gamergates</strong><br />

<strong>is</strong> similar to having one vs multiple <strong>queen</strong>s with respect<br />

to colony kin structure.<br />

The fact that multiple-gamergate societies often have<br />

winged <strong>queen</strong>s (Table 2) complicates the compar<strong>is</strong>on with<br />

single-gamergate societies, which typically lack <strong>queen</strong>s<br />

(Table 1). Thus we need to consider separately species that<br />

have lost the <strong>queen</strong> caste from those that have retained it.<br />

Among species that lack <strong>queen</strong>s, gamergate number <strong>is</strong> not<br />

associated with clear differences in ecological requirements<br />

of colonies. Colony f<strong>is</strong>sion occurs irrespective of whether<br />

there are one or multiple <strong>gamergates</strong>. Gamergate colonies<br />

are potentially immortal because <strong>an</strong>y young worker c<strong>an</strong><br />

replace a dying gamergate, provided that foreign males are<br />

present. In contrast, monogynous colonies of “classical”<br />

<strong>an</strong>ts will often go extinct upon the death of the founding<br />

<strong>queen</strong>, whereas polygynous colonies will not as they typically<br />

readopt young <strong>queen</strong>s. Hence, single- <strong>an</strong>d multiplegamergate<br />

societies do not differ in terms of long-term<br />

stability or capacity to reproduce by f<strong>is</strong>sion, <strong>an</strong>d do not<br />

seem to represent d<strong>is</strong>tinct “syndromes”.<br />

It <strong>is</strong> not surpr<strong>is</strong>ing that some species with <strong>gamergates</strong><br />

have retained winged <strong>queen</strong>s. Although independent colony<br />

foundation <strong>is</strong> r<strong>is</strong>ky, it c<strong>an</strong> yield large benefits such as<br />

colon<strong>is</strong>ing a d<strong>is</strong>t<strong>an</strong>t patch of suitable habitat. Species in<br />

which both <strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d <strong>gamergates</strong> reproduce are comparable<br />

to “classical” <strong>an</strong>ts having two <strong>queen</strong> phenotypes, i.e.<br />

macrogynes <strong>an</strong>d microgynes, or <strong>queen</strong>s with <strong>an</strong>d without<br />

stored energetic reserves (e.g. Rosengren et al. 1993;<br />

Heinze <strong>an</strong>d Keller 2000; Rüppell et al. 2001). Presumably,

114 Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften (2008) 95:109–116<br />

gamergate species in which <strong>queen</strong>s were eliminated have<br />

experienced stronger selection against independent colony<br />

foundation relative to species that retained <strong>queen</strong>s. One<br />

hypothes<strong>is</strong> for the retention of the <strong>queen</strong> caste <strong>is</strong> that<br />

species having both <strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d <strong>gamergates</strong> live in more<br />

unstable or patchier environments, where the capacity to<br />

d<strong>is</strong>perse over long d<strong>is</strong>t<strong>an</strong>ces <strong>is</strong> strongly favoured. Indeed,<br />

restricted d<strong>is</strong>persal has been shown in a species without<br />

<strong>queen</strong>s (Doums et al. 2002). <strong>How</strong>ever, our knowledge of<br />

the biology <strong>an</strong>d ecology of <strong>an</strong>ts with <strong>gamergates</strong> <strong>is</strong> too<br />

limited to test th<strong>is</strong> hypothes<strong>is</strong>.<br />

Bourke (1999) argues that colony size <strong>an</strong>d social complexity<br />

are key determin<strong>an</strong>ts of social insect biology. All<br />

species with <strong>gamergates</strong> have small colonies (Tables 1 <strong>an</strong>d 2)<br />

compared to that of higher <strong>an</strong>ts, which c<strong>an</strong> reach hundreds of<br />

thous<strong>an</strong>ds of workers. <strong>How</strong>ever, single-gamergate species<br />

(or genera) have smaller colonies th<strong>an</strong> multiple-gamergate<br />

species (genera). Why? Gamergates generally have low<br />

fertility (because they belong to the worker caste), <strong>an</strong>d th<strong>is</strong><br />

may limit colony size in single-gamergate species. <strong>How</strong>ever,<br />

intra-specific compar<strong>is</strong>ons suggest that th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> not the whole<br />

story. Among species where gamergate number varies<br />

among colonies, single-gamergate colonies are smaller th<strong>an</strong><br />

multiple-gamergate colonies in Rhytidoponera aurata<br />

(Komene et al. 1999), but there <strong>is</strong> no difference in<br />

Amblyopone sp. (Ito 1993b), G. menadens<strong>is</strong> (Gobin et al.<br />

2001), Leptogenys peuqueti (Ito 1997) <strong>an</strong>dPachycondyla<br />

(Ophthalmopone) berthoudi (Peeters <strong>an</strong>d Crewe 1984;<br />

Sledge et al. 1996, 1999, 2001). Th<strong>is</strong> lack of a correlation<br />

between gamergate number <strong>an</strong>d colony size may be explained<br />

by a decrease in individual fertility as breeder number r<strong>is</strong>es<br />

(P. berthoudi, Sledge et al. 1996).<br />

Based on what <strong>is</strong> known about the life h<strong>is</strong>tory of 46<br />

species with <strong>gamergates</strong>, we propose that the evolution of<br />

gamergate number <strong>an</strong>d the loss of the <strong>queen</strong> caste follows<br />

a general pattern. Firstly, reproduction by multiple <strong>gamergates</strong><br />

evolves due to the adaptive benefits of secondary<br />

polygyny, i.e. increased colony lifesp<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d resource inherit<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

(Peeters <strong>an</strong>d Ito 2001), <strong>an</strong>d <strong>gamergates</strong> coex<strong>is</strong>t<br />

with <strong>queen</strong>s. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> likely the case in species where colonies<br />

are obligatorily founded by a <strong>queen</strong> (i.e. H. saltator,<br />

Peeters <strong>an</strong>d Hölldobler 1995; Peeters et al. 2000). Secondly,<br />

winged <strong>queen</strong>s are lost whenever independent colony<br />

foundation <strong>is</strong> no longer selected for, giving r<strong>is</strong>e to species<br />

where multiple <strong>gamergates</strong> are the sole reproductives.<br />

Thirdly, gamergate number <strong>is</strong> reduced, <strong>an</strong>d th<strong>is</strong> gives r<strong>is</strong>e<br />

to single-gamergate species. Th<strong>is</strong> pattern <strong>is</strong> supported by<br />

the lack of a <strong>queen</strong> caste in almost all single-gamergate<br />

species vs only half the multiple-gamergate species. One or<br />

more of these three stages are found in each genus having<br />

<strong>gamergates</strong>. Future studies must investigate whether reduction<br />

in gamergate number increases colony efficiency, e.g.<br />

by reducing the number of hopeful reproductive workers<br />

(Molet et al. 2005) <strong>an</strong>d by reducing their probability of<br />

becoming gamergate <strong>an</strong>d thus increasing their helping<br />

effort (Field et al. 2006). To conclude, how <strong>m<strong>an</strong>y</strong> <strong>gamergates</strong><br />

<strong>is</strong> a <strong>queen</strong> <strong>worth</strong>? With respect to long-r<strong>an</strong>ge<br />

d<strong>is</strong>persal, winged <strong>queen</strong>s are irreplaceable, which <strong>is</strong> why<br />

<strong>m<strong>an</strong>y</strong> gamergate species have retained the <strong>queen</strong> caste.<br />

Acknowledgements We th<strong>an</strong>k Claudie Doums, Fuminori Ito <strong>an</strong>d<br />

Jürgen Heinze for constructive d<strong>is</strong>cussions <strong>an</strong>d comments, as well as<br />

two <strong>an</strong>onymous referees for useful suggestions.<br />

References<br />

André J-B, Peeters C, Doums C (2001) Serial polygyny <strong>an</strong>d colony<br />

genetic structure in the monogynous <strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>t Diacamma<br />

cy<strong>an</strong>eiventre. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 50:72–80<br />

Blatrix R (2000) Aspects éthologiques et sociobiologiques de la<br />

polygynie chez une fourmi ponerine (Gnamptogenys striatula).<br />

Ph.D. thes<strong>is</strong>, Université Par<strong>is</strong> Nord, Fr<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

Blatrix R, Ja<strong>is</strong>son P (2000) Optional <strong>gamergates</strong> in the <strong>queen</strong>right ponerine<br />

<strong>an</strong>t Gnamptogenys striatula Mayr. Insectes Soc 47:193–197<br />

Bolton B (2003) Synops<strong>is</strong> <strong>an</strong>d classification of Formicidae. Mem Am<br />

Entomol Inst, 71:370<br />

Bourke AFG (1999) Colony size, social complexity <strong>an</strong>d reproductive<br />

conflict in social insects. J Evol Biol 12:245–257<br />

Bourke AFG, Fr<strong>an</strong>ks NR (1995) Social evolution in <strong>an</strong>ts. Princeton<br />

University Press, Princeton, p 529<br />

Brady SG, Schultz TR, F<strong>is</strong>her BR, Ward PS (2006) Evaluating<br />

alternative hypotheses for the early evolution <strong>an</strong>d diversification<br />

of <strong>an</strong>ts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:18172–18177<br />

Chapu<strong>is</strong>at M, Crozier R (2001). Low relatedness among cooperatively<br />

breeding workers of the greenhead <strong>an</strong>t Rhytidoponera metallica.<br />

J Evol Biol 14:564–573<br />

Crozier RH, Pamilo P (1996) Evolution of social insect colonies. Sex<br />

allocation <strong>an</strong>d kin selection. Oxford University Press, Oxford,<br />

p 306<br />

Cuvillier-Hot V (2002) Domin<strong>an</strong>ce et fertilité chez la fourmi s<strong>an</strong>s<br />

reine Streblognathus peetersi. Ph.D. thes<strong>is</strong>, Université Fr<strong>an</strong>ço<strong>is</strong><br />

Rabela<strong>is</strong>-Tours, Fr<strong>an</strong>ce<br />

Cuvillier-Hot V, Cobb M, Malosse C, Peeters C (2001) Sex, age <strong>an</strong>d<br />

ovari<strong>an</strong> activity affect cuticular hydrocarbons in Diacamma<br />

ceylonense, a <strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>t. J Insect Physiol 47:485–493<br />

Davies SJ, Villet MH, Blomefield TM, Crewe RM (1994) Reproduction<br />

<strong>an</strong>d div<strong>is</strong>ion of labour in Leptogenys schwabi Forel (Hymenoptera<br />

Formicidae), a multiple-<strong>gamergates</strong>, <strong>queen</strong>less ponerine <strong>an</strong>t. Ethol<br />

Ecol Evol 6:507–517<br />

Doums C, Cabrera H, Peeters C (2002) Population genetic structure<br />

<strong>an</strong>d male-biased d<strong>is</strong>persal in the <strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>t Diacamma<br />

cy<strong>an</strong>eiventre. Mol Ecol 11:2251–2264<br />

Field J, Cronin A, Bridge C (2006) Future fitness <strong>an</strong>d helping in social<br />

queues. Nature 441:214–217<br />

Fourcassié V, Oliveira P (2002) Foraging ecology of the gi<strong>an</strong>t <strong>an</strong>t<br />

Dinoponera gig<strong>an</strong>tea (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Ponerinae):<br />

activity schedule, diet, <strong>an</strong>d spatial foraging patterns. J Nat H<strong>is</strong>t<br />

36:2211–2227<br />

Fowler HG (1985) Populations, foraging <strong>an</strong>d territoriality in Dinoponera<br />

austral<strong>is</strong> (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Rev Bras Entomol 29:443–<br />

447<br />

Fukumoto Y, Abe T, Taki A (1989) A novel form of colony<br />

org<strong>an</strong>ization in the “<strong>queen</strong>less” <strong>an</strong>t Diacamma rugosum. Physiol<br />

Ecol Jap<strong>an</strong> 26:55–61

Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften (2008) 95:109–116 115<br />

Gobin B, Peeters C, Billen J (1998) Colony reproduction <strong>an</strong>d arboreal life<br />

in the ponerine <strong>an</strong>t Gnamptogenys menadens<strong>is</strong> (Hymenoptera:<br />

Formicidae). Neth J Zool 48:53–63<br />

Gobin B, Billen J, Peeters C (2001) Domin<strong>an</strong>ce interactions regulate<br />

worker mating in the multiple-<strong>gamergates</strong> ponerine <strong>an</strong>t<br />

Gnamptogenys menadens<strong>is</strong>. Ethology 107:495–508<br />

Heinze J, Keller L (2000) Alternative reproductive strategies: a <strong>queen</strong><br />

perspective in <strong>an</strong>ts. Trends Ecol Evol 15:508–512<br />

Higashi S, Ito F, Sugiura N, Ohkawara K (1994) Worker’s age regulates<br />

the linear domin<strong>an</strong>ce hierarchy in the <strong>queen</strong>less ponerine <strong>an</strong>t,<br />

Pachycondyla sublaev<strong>is</strong> (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Anim Behav<br />

47:179–184<br />

Ito F (1993a) Functional monogyny <strong>an</strong>d domin<strong>an</strong>ce hierarchy in the<br />

<strong>queen</strong>less ponerine <strong>an</strong>t Pachycondyla (=Bothroponera) sp. in<br />

west Java, Indonesia. Ethology 95:126–140<br />

Ito F (1993b) Social org<strong>an</strong>ization in a primitive ponerine <strong>an</strong>t:<br />

<strong>queen</strong>less reproduction, domin<strong>an</strong>ce hierarchy <strong>an</strong>d functional<br />

polygyny in Amblyopone sp. (Reclinata group) (Hymenoptera:<br />

Formicidae: Ponerinae). J Nat H<strong>is</strong>t 27:1315–1324<br />

Ito F (1994) Colony composition of two Malaysi<strong>an</strong> ponerine <strong>an</strong>ts,<br />

Platythyrea tricuspidata <strong>an</strong>d P. quadridenta: sexual reproduction<br />

by workers <strong>an</strong>d production of <strong>queen</strong>s (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).<br />

Psyche 101:209–218<br />

Ito F (1997) Colony composition <strong>an</strong>d morphological caste differentiation<br />

between ergatoid <strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d workers in the ponerine <strong>an</strong>t<br />

genus Leptogenys in the oriental tropics. Ethol Ecol Evol 9:335–<br />

343<br />

Ito F, Higashi S (1991) A linear domin<strong>an</strong>ce hierarchy regulating<br />

reproduction <strong>an</strong>d polyeth<strong>is</strong>m of the <strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>t Pachycondyla<br />

sublaev<strong>is</strong>. Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften 78:80–82<br />

Jahyny B, Delabie J, Fresneau, D (2002) Mini-sociétés s<strong>an</strong>s reine chez<br />

le genre néotropical Thaumatomyrmex Mayr, 1887 (Formicidae:<br />

Ponerinae). Actes Colloq Insectes Soc 15:33–37<br />

Karpakakunjaram V, Nair P, Varghese T, Royappa G, Kolatkar M,<br />

Gadagkar R (2003) Contributions to the biology of the <strong>queen</strong>less<br />

ponerine <strong>an</strong>t, Diacamma ceylonense, Emery (Formicidae). J Bombay<br />

Nat H<strong>is</strong>t Soc 100:533–543<br />

Kawabata S, Tsuji K (2005) The policing behavior ‘immobilization’<br />

towards ovary-developed workers in the <strong>an</strong>t, Diacamma sp from<br />

Jap<strong>an</strong>. Insectes Soc 52:89–95<br />

Komene Y, Higashi S, Ito F, Miyata H (1999) Effect of colony size on<br />

the number of <strong>gamergates</strong> in the <strong>queen</strong>less ponerine <strong>an</strong>t<br />

Rhytidoponera aurata. Insectes Soc 46:29–33<br />

Liebig J, Hölldobler B, Peeters C (1998) Are <strong>an</strong>t workers capable of<br />

colony foundation? Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften 85:133–135<br />

Molet M, v<strong>an</strong> Baalen M, Monnin T (2005) Domin<strong>an</strong>ce hierarchies<br />

reduce the number of hopeful reproductives in polygynous<br />

<strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>ts. Insectes Soc 52:247–256<br />

Monnin T, Peeters C (1999) Domin<strong>an</strong>ce hierarchy <strong>an</strong>d reproductive<br />

conflicts among subordinates in a monogynous <strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>t.<br />

Behav Ecol 10:323–332<br />

Moreau CS, Bell CD, Vila R, Archibald SB, Pierce NE (2006)<br />

Phylogeny of the <strong>an</strong>ts: diversification in the age of <strong>an</strong>giosperms.<br />

Science 312:101–104<br />

Overal WL (1980) Observation on colony founding <strong>an</strong>d migration of<br />

Dinoponera gig<strong>an</strong>tea. J Ga Entomol Soc 15:466–469<br />

Paiva RVS (1997) Org<strong>an</strong>ização social de Dinoponera austral<strong>is</strong> Emery<br />

(Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ph.D. thes<strong>is</strong>, Universidade de São<br />

Paulo, Brasil<br />

Paiva RVS, Br<strong>an</strong>dão CRF (1995) Nests, worker population, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

reproductive status of workers, in the true gi<strong>an</strong>t <strong>queen</strong>less<br />

ponerine <strong>an</strong>t Dinoponera Roger (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).<br />

Ethol Ecol Evol 7:297–312<br />

Pamilo P, Crozier RH, Fraser J (1985) Inter-nest interactions, nest<br />

autonomy, <strong>an</strong>d reproductive specialization in <strong>an</strong> Australi<strong>an</strong> aridzone<br />

<strong>an</strong>t, Rhytidoponera sp. 12. Psyche 92:217–236<br />

Peeters C (1987) The reproductive div<strong>is</strong>ion of labour in the <strong>queen</strong>less<br />

ponerine <strong>an</strong>t Rhytidoponera sp. 12. Insectes Soc 34:75–86<br />

Peeters C (1993) Monogyny <strong>an</strong>d polygyny in ponerine <strong>an</strong>ts with or<br />

without <strong>queen</strong>s. In: Keller L (ed) Queen number <strong>an</strong>d sociality in<br />

insects. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 234–261<br />

Peeters C (1997) Morphologically “primitive” <strong>an</strong>ts: comparative<br />

review of social characters, <strong>an</strong>d the import<strong>an</strong>ce of <strong>queen</strong>-worker<br />

dimorph<strong>is</strong>m. In: Choe J, Crespi B (eds) The evolution of social<br />

behavior in insects <strong>an</strong>d arachnids. Cambridge University Press,<br />

Cambridge, pp 372–391<br />

Peeters C, Crewe R (1984) Insemination controls the reproductive<br />

div<strong>is</strong>ion of labour in a ponerine <strong>an</strong>t. Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften 71:50–51<br />

Peeters C, Crewe R (1985) Worker reproduction in the ponerine <strong>an</strong>t<br />

Ophthalmopone berthoudi: <strong>an</strong> alternative form of eusocial<br />

org<strong>an</strong>ization. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 18:29–37<br />

Peeters C, Crewe R (1986) Queenright <strong>an</strong>d <strong>queen</strong>less breeding systems<br />

within the genus Pachycondyla (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J<br />

EntomolSocSouthAfr49:251–255<br />

Peeters C, Higashi S (1989) Reproductive domin<strong>an</strong>ce controlled by mutilation<br />

in the <strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>t Diacamma australe. Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften<br />

76:177–180<br />

Peeters C, Hölldobler B (1995) Reproductive cooperation between<br />

<strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d their mated workers: the complex life h<strong>is</strong>tory of <strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>t<br />

with a valuable nest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:10977–10979<br />

Peeters C, Ito F (2001) Colony d<strong>is</strong>persal <strong>an</strong>d the evolution of <strong>queen</strong><br />

morphology in social Hymenoptera. Annu Rev Entomol 48:601–<br />

630<br />

Peeters C, Higashi S, Ito F (1991) Reproduction in ponerine <strong>an</strong>ts<br />

without <strong>queen</strong>s: monogyny <strong>an</strong>d exceptionally small colonies in the<br />

australi<strong>an</strong> Pachycondyla sublaev<strong>is</strong>. Ethol Ecol Evol 3:145–152<br />

Peeters C, Liebig L, Hölldobler B (2000) Sexual reproduction by both<br />

<strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d workers in the ponerine <strong>an</strong>t Harpegnathos saltator.<br />

Insectes Soc 47:325–332<br />

Rosengren R, Sundström L, Fortelius W (1993) Monogyny <strong>an</strong>d<br />

polygyny in Formica <strong>an</strong>ts: the results of alternative d<strong>is</strong>persal<br />

tactics. In: Keller L (ed) Queen number <strong>an</strong>d sociality in insects.<br />

Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 308–333<br />

Ross KG, Keller L (1995) Ecology <strong>an</strong>d evolution of social<br />

Org<strong>an</strong>ization: insights from fire <strong>an</strong>ts <strong>an</strong>d other highly eusocial<br />

insects. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 26:631–656<br />

Rüppell O, Heinze J, Hölldobler B (2001) Alternative reproductive<br />

tactics in the <strong>queen</strong>-size-dimorphic <strong>an</strong>t Leptothorax rugatulus<br />

(Emery) <strong>an</strong>d their consequences for genetic population structure.<br />

Behav Ecol Sociobiol 50:189–197<br />

Sledge MF, Crewe RM, Peeters RP (1996) On the relationship<br />

between <strong>gamergates</strong> number <strong>an</strong>d reproductive output in the<br />

<strong>queen</strong>less ponerine <strong>an</strong>t Pachycondyla (=Ophthalmopone)<br />

berthoudi. Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften 83:282–284<br />

Sledge MF, Peeters C, Crewe RM (1999) Fecundity <strong>an</strong>d the<br />

behavioural profile of reproductive workers in the <strong>queen</strong>less<br />

<strong>an</strong>t, Pachycondyla (=Ophthalmopone) berthoudi. Ethology<br />

105:303–316<br />

Sledge MF, Peeters C, Crewe RM (2001) Reproductive div<strong>is</strong>ion of<br />

labour without domin<strong>an</strong>ce interactions in the <strong>queen</strong>less ponerine<br />

<strong>an</strong>t Pachycondyla (=Ophthalmopone) berthoudi. Insectes Soc<br />

48:67–73<br />

Sommer K, Hölldobler B (1992) Coex<strong>is</strong>tence <strong>an</strong>d domin<strong>an</strong>ce among<br />

<strong>queen</strong>s <strong>an</strong>d mated workers in the <strong>an</strong>t Pachycondyla tridentata.<br />

Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften 79:470–472<br />

Sommer K, Hölldobler B, Rembold H (1993) Behavioral <strong>an</strong>d<br />

physiological aspects of reproductive control in a Diacamma<br />

species from Malaysia (Formicidae, Ponerinae). Ethology<br />

94:162–170<br />

Sommer K, Hölldobler B, Jessen K (1994) The unusual social<br />

org<strong>an</strong>ization of the <strong>an</strong>t Pachycondyla tridentata (Formicidae,<br />

Ponerinae). J Ethol 12:175–185

116 Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften (2008) 95:109–116<br />

Sundström L, Seppä P, Pamilo P (2005) Genetic population structure<br />

<strong>an</strong>d d<strong>is</strong>persal patterns in Formica <strong>an</strong>ts—a review. Ann Zool Fenn<br />

42:163–177<br />

Tay WT, Crozier RH (2000) Nestmate interactions <strong>an</strong>d egg-laying<br />

behaviours in the <strong>queen</strong>less ponerine <strong>an</strong>t Rhytidoponera sp. 12.<br />

Insectes Soc 47:133–140<br />

Thomas ML, Elgar MA (2003) Colony size affects div<strong>is</strong>ion of labour in<br />

the ponerine <strong>an</strong>t Rhytidoponera metallica. Naturw<strong>is</strong>senschaften<br />

90:88–92<br />

Tschinkel WR (2006) The fire <strong>an</strong>t. Harvard University Press, Cambridge,<br />

p744<br />

Vasconcellos A, S<strong>an</strong>t<strong>an</strong>a GG, Souza AK (2004) Nest spacing <strong>an</strong>d<br />

architecture, <strong>an</strong>d swarming of males of Dinoponera quadriceps<br />

(Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in a remn<strong>an</strong>t of the Atl<strong>an</strong>tic Forest in<br />

Northeast Brazil. Braz J Biol 64:357–362<br />

Villet MH (1991) Social differentiation <strong>an</strong>d div<strong>is</strong>ion of labour in the<br />

<strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>t Platythyrea schultzei forel 1910 (Hymenoptera<br />

Formicidae). Trop Zool 4:13–29<br />

Villet MH (1992) The social biology of Hagensia havil<strong>an</strong>di (Forel 1901)<br />

(Hymenoptera Formicidae), <strong>an</strong>d the origin of <strong>queen</strong>lessness in<br />

ponerine <strong>an</strong>ts. Trop Zool 5:195–206<br />

Villet MH, Wildm<strong>an</strong> MH (1991) Div<strong>is</strong>ion of labour in the obligately<br />

<strong>queen</strong>less <strong>an</strong>t Pachycondyla (=Bothroponera) krugeri Forel 1910<br />

(Hymenoptera Formicidae). Trop Zool 4:233–250<br />

Villet MH, Hart A, Crewe RM (1990) Social org<strong>an</strong>ization of Platythyrea<br />

lamellosa (Roger) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): I. Reproduction. S<br />

Afr J Zool 25:250–253<br />

Walin L, Seppä P, Sundström L (2001) Reproductive allocation within<br />

a polygyne, polydomous colony of the <strong>an</strong>t Myrmica rubra. Ecol<br />

Entomol 26:537–546<br />

Ward PS (1983) Genetic relatedness <strong>an</strong>d colony org<strong>an</strong>ization in a<br />

species complex of ponerine <strong>an</strong>ts: I. Phenotypic <strong>an</strong>d genotypic<br />

composition of colonies. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 12:285–299<br />

Ward PS (1986) Functional <strong>queen</strong>s in the Australi<strong>an</strong> greenhead <strong>an</strong>t,<br />

Rhytidoponera metallica (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche<br />

93:1–12<br />

Ware AB, Compton SG, Robertson HG (1990) Gamergate reproduction<br />

in the <strong>an</strong>t Streblognathus aethiopicus Smith (Hymenoptera:<br />

Formicidae: Ponerinae). Insectes Soc 37:189–199<br />

Wildm<strong>an</strong> MH, Crewe RM (1988) Gamergate number <strong>an</strong>d control over<br />

reproduction in Pachycondyla krugeri (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).<br />

Insectes Soc 35:217–225