View PDF Version - RePub - Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam

View PDF Version - RePub - Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam

View PDF Version - RePub - Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Future research should unravel whether a gradual overall decay of transcriptional<br />

capacity, whether or not caused by DNA lesions, underlies aspects of human aging .<br />

Cys!ein·rich matrix<br />

proteins (cuticle)<br />

Cysteln-rich malJix<br />

protelna (coI\ex)<br />

High glycineltyrO$ine !emUn<br />

Intanned/ate filament leralln<br />

Hair Skin<br />

......- Sll'atum oomeum<br />

......- Gl8l'V.J1ar 18j6I"<br />

(ioricrin, SPRR2)<br />

......- Spinous lever<br />

(K1,K10)<br />

......- Besallajer<br />

(Ks, K14)<br />

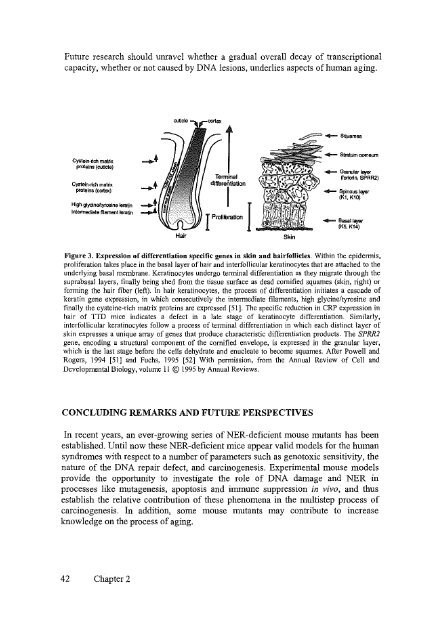

Figure 3, Expression of differentiation specific genes in skin and hairfollicles. Within the epidermis,<br />

proliferation takes place in the basal layer of hair and interfollicular keratinocytes that are attached to the<br />

underlying basal membrane. Keratinocytes undergo terminal differentiation as they migrate through the<br />

suprabasallayers, finally being shed from the tissue surface as dead cornified squarnes (skin, right) or<br />

forming the hair fiber (left). In hair keratinocytes, the process of differentiation initiates a cascade of<br />

keratin gene expression, in which consecutively the intermediate filaments, high glycine/tyrosine and<br />

finally the cysteine-rich matrix proteins are expressed [51]. The specific reduction in CRP expression in<br />

hair of TTD mice indicates a defect in a late stage of keratinocyte differentiation. Similarly,<br />

interfollicular keratinocytes follow a process of terminal differentiation in which each distinct layer of<br />

skin expresses a unique array of genes that produce characteristic differentiation products. The SPRR2<br />

gene, encoding a structural component of the cornified envelope, is expressed in the granular layer,<br />

which is the last stage before the cells dehydrate and enucleate to become squames. After Powell and<br />

Rogers, 1994 [51] and Fuchs, 1995 [52] With permission, from the Annual Review of Cel1 and<br />

Developmental Biology, volume 11 © 1995 by Annual Reviews.<br />

CONCLUDING REMARKS AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES<br />

In recent years, an ever-growing series of NER-deficient mouse mutants has been<br />

established. Until now these NER-deficient mice appear valid models for the human<br />

syndromes with respect to a number of parameters such as genotoxic sensitivity, the<br />

nature of the DNA repair defect, and carcinogenesis. Experimental mouse models<br />

provide the opportnnity to investigate the role of DNA damage and NER in<br />

processes like mutagenesis, apoptosis and immune suppression in vivo, and thus<br />

establish the relative contribution of these phenomena in the multistep process of<br />

carcinogenesis. In addition, some mouse mutants may contribute to increase<br />

knowledge on the process of aging.<br />

42 Chapter 2