A prolific painter of portraits before and after the French Revolution ...

A prolific painter of portraits before and after the French Revolution ...

A prolific painter of portraits before and after the French Revolution ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 302<br />

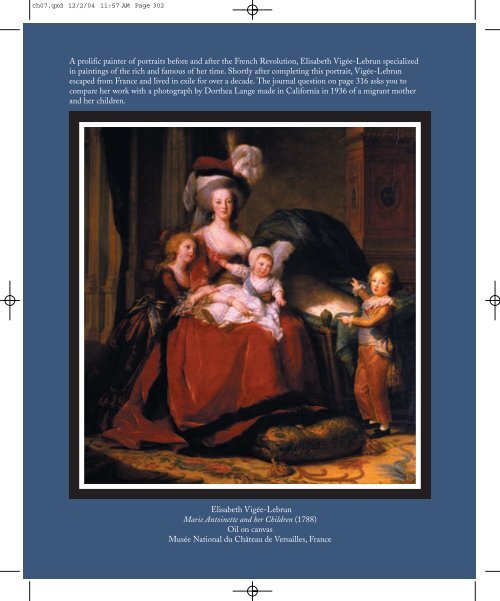

A <strong>prolific</strong> <strong>painter</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>portraits</strong> <strong>before</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>after</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>French</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong>, Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun specialized<br />

in paintings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rich <strong>and</strong> famous <strong>of</strong> her time. Shortly <strong>after</strong> completing this portrait, Vigée-Lebrun<br />

escaped from France <strong>and</strong> lived in exile for over a decade. The journal question on page 316 asks you to<br />

compare her work with a photograph by Dor<strong>the</strong>a Lange made in California in 1936 <strong>of</strong> a migrant mo<strong>the</strong>r<br />

<strong>and</strong> her children.<br />

Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun<br />

Marie Antoinette <strong>and</strong> her Children (1788)<br />

Oil on canvas<br />

Musée National du Château de Versailles, France

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 303<br />

chapter<br />

Explaining<br />

ou have decided to quit your present job, so you write a note to your boss<br />

giving thirty days’ notice. During your last few weeks at work, your<br />

boss asks you to write a three-page job description to help orient <strong>the</strong><br />

person who will replace you. The job description should include a list <strong>of</strong> your current<br />

duties as well as advice to your replacement on how to execute <strong>the</strong>m most efficiently.<br />

To write <strong>the</strong> description, you record your daily activities, look back through<br />

your calendar, comb through your records, <strong>and</strong> brainstorm a list <strong>of</strong> everything you<br />

do. As you write up <strong>the</strong> description, you include specific examples <strong>and</strong> illustrations<br />

<strong>of</strong> your typical responsibilities.<br />

s a gymnast <strong>and</strong> dancer, you gradually become obsessed with losing<br />

weight. You start skipping meals, purging <strong>the</strong> little food you do eat,<br />

<strong>and</strong> lying about your eating habits to your parents. Before long, you<br />

weigh less than seventy pounds, <strong>and</strong> your physician diagnoses your condition:<br />

anorexia nervosa. With advice from your physician <strong>and</strong> counseling from a psychologist,<br />

you gradually begin to control your disorder. To explain to o<strong>the</strong>rs what<br />

anorexia is, how it is caused, <strong>and</strong> what its effects<br />

are, you write an essay in which you explain your<br />

ordeal, alerting o<strong>the</strong>r readers to <strong>the</strong> potential<br />

dangers <strong>of</strong> uncontrolled dieting.<br />

‘‘<br />

Become aware <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> two-sided nature<br />

<strong>of</strong> your mental<br />

make-up: one<br />

thinks in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

he connectedness <strong>of</strong><br />

things, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

thinks in terms <strong>of</strong><br />

parts <strong>and</strong><br />

sequences.<br />

’’<br />

— GABRIELE LUSSER<br />

‘‘<br />

RICO,<br />

AUTHOR OF WRITING<br />

THE NATURAL WAY<br />

What [a writer]<br />

knows is almost<br />

always a matter <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> relationships he<br />

establishes, between<br />

example <strong>and</strong><br />

generalization,<br />

between one part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

narrative <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

next, between <strong>the</strong><br />

idea <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

counter idea that<br />

<strong>the</strong> writer sees is<br />

also relevant.<br />

’’<br />

— ROGER SALE,<br />

AUTHOR OF<br />

ON WRITING<br />

303

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 304<br />

304<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

XPLAINING AND DEMONSTRATING RELATIONSHIPS IS A FREQUENT PURPOSE<br />

BACKGROUND ON<br />

EXPLAINING<br />

This chapter assumes that<br />

expository writing <strong>of</strong>ten includes<br />

some mixture <strong>of</strong><br />

definition, process analysis,<br />

<strong>and</strong> causal analysis. Although<br />

a completed essay<br />

may use just one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se as<br />

a primary strategy, a writer<br />

needs a choice <strong>of</strong> expository<br />

strategies for <strong>the</strong><br />

thinking, learning, <strong>and</strong><br />

composing process.<br />

ESL TEACHING TIP<br />

Academic writing in <strong>the</strong><br />

United States is primarily<br />

expository writing, <strong>and</strong> it is<br />

culturally bound. Your ESL<br />

students may have very different<br />

expectations about<br />

<strong>the</strong> purpose, form, <strong>and</strong> style<br />

<strong>of</strong> academic writing. Discussing<br />

Robert Kaplan’s<br />

ideas about contrastive<br />

rhetoric—in class or in a<br />

conference—will allow your<br />

ESL students to underst<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> seemingly strange<br />

<strong>and</strong> arbitrary conventions<br />

<strong>of</strong> U.S. academic writing.<br />

FOR WRITING. EXPLAINING GOES BEYOND INVESTIGATING THE FACTS AND<br />

REPORTING INFORMATION; IT ANALYZES THE COMPONENT PARTS OF A SUBject<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n shows how <strong>the</strong> parts fit in relation to one ano<strong>the</strong>r. Its goal is to<br />

clarify for a particular group <strong>of</strong> readers what something is, how it happened<br />

or should happen, <strong>and</strong>/or why it happens.<br />

Explaining begins with assessing <strong>the</strong> rhetorical situation: <strong>the</strong> writer, <strong>the</strong> occasion,<br />

<strong>the</strong> intended purpose <strong>and</strong> audience, <strong>the</strong> genre, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> cultural context. As you<br />

begin thinking about a subject, topic, or issue to explain, keep in mind your own interests,<br />

<strong>the</strong> expectations <strong>of</strong> your audience, <strong>the</strong> possible genre you might choose to help<br />

achieve your purpose (essay, article, pamphlet, multigenre essay, Web site), <strong>and</strong> finally<br />

<strong>the</strong> cultural or social context in which you are writing or in which your writing might<br />

be read.<br />

Explaining any idea, concept, process, or effect requires analysis. Analysis starts<br />

with dividing a thing or phenomenon into its various parts. Then, once you explain<br />

<strong>the</strong> various parts, you put <strong>the</strong>m back toge<strong>the</strong>r (syn<strong>the</strong>sis) to explain <strong>the</strong>ir relationship<br />

or how <strong>the</strong>y work toge<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Explaining how to learn to play <strong>the</strong> piano, for example, begins with an analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> learning process: playing scales, learning chords, getting instruction<br />

from a teacher, sight reading, <strong>and</strong> performing in recitals. Explaining why two<br />

automobiles collided at an intersection begins with an analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> contributing<br />

factors: <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> intersection, <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> cars involved, <strong>the</strong> condition <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> drivers, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> condition <strong>of</strong> each vehicle. Then you bring <strong>the</strong> parts toge<strong>the</strong>r<br />

<strong>and</strong> show <strong>the</strong>ir relationships: you show how practicing scales on <strong>the</strong> piano fits into<br />

<strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> learning to play <strong>the</strong> piano; you demonstrate why one small factor—<br />

such as a faulty turn signal—combined with o<strong>the</strong>r factors to cause an automobile accident.<br />

The emphasis you give to <strong>the</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> object or phenomenon <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

time you spend explaining relationships <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> parts depends on your purpose, subject,<br />

<strong>and</strong> audience. If you want to explain how a flower reproduces, for example, you<br />

may begin by identifying <strong>the</strong> important parts, such as <strong>the</strong> pistil <strong>and</strong> stamen, that<br />

most readers need to know about <strong>before</strong> <strong>the</strong>y can underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> reproductive<br />

process. However, if you are explaining <strong>the</strong> process to a botany major who already<br />

knows <strong>the</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> a flower, you might spend more time discussing <strong>the</strong> key operations<br />

in pollination or <strong>the</strong> reasons why some flowers cross-pollinate <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs do<br />

not. In any effective explanation, analyzing parts <strong>and</strong> showing relationships must<br />

work toge<strong>the</strong>r for that particular group <strong>of</strong> readers.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 305<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

305<br />

Because its purpose is to teach <strong>the</strong> reader, expository writing, or writing to explain,<br />

should be as clear as possible. Explanations, however, are more than organized<br />

pieces <strong>of</strong> information. Expository writing contains information that is focused by your<br />

point <strong>of</strong> view, by your experience, <strong>and</strong> by your reasoning powers. Thus, your explanation<br />

<strong>of</strong> a thing or phenomenon makes a point or has a <strong>the</strong>sis: This is <strong>the</strong> right way<br />

to define happiness. This is how one should bake lasagne or do a calculus problem.<br />

These are <strong>the</strong> most important reasons why <strong>the</strong> senator from New York was elected.<br />

To make your explanation clear, you show what you mean by using specific support:<br />

facts, data, examples, illustrations, statistics, comparisons, analogies, <strong>and</strong> images.<br />

Your <strong>the</strong>sis is a general assertion about <strong>the</strong> relationships <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> specific parts. The support<br />

helps your reader identify <strong>the</strong> parts <strong>and</strong> see <strong>the</strong> relationships. Expository writing<br />

teaches <strong>the</strong> reader by alternating between generalizations <strong>and</strong> specific examples.<br />

Techniques for Explaining<br />

Explaining requires first that you assess your rhetorical situation. Your purpose must<br />

work for a particular audience, genre, <strong>and</strong> context. You may revise some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se aspects<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rhetorical situation as you draw on your own observations <strong>and</strong> memories<br />

about your topic. As you research your topic, conduct an interview, or do a survey,<br />

keep thinking about issues <strong>of</strong> audience, genre, <strong>and</strong> context. Below are techniques for<br />

writing clear explanations.<br />

‘‘<br />

The main thing<br />

I try to do is write as<br />

clearly as I can.<br />

’’<br />

— E . B . WHITE,<br />

JOURNALIST AND<br />

COAUTHOR OF<br />

ELEMENTS OF STYLE<br />

• Considering (<strong>and</strong> reconsidering) your purpose, audience, genre, <strong>and</strong> social<br />

context. As you change your audience or your genre, for example, you<br />

must change how you explain something as well as how much <strong>and</strong> what<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> evidence <strong>and</strong> support you use.<br />

• Getting <strong>the</strong> reader’s attention <strong>and</strong> stating <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>sis. Devise an accurate<br />

but interesting title. Use an attention-getting lead-in. State <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>sis<br />

clearly.<br />

• Defining key terms <strong>and</strong> describing what something is. Analyze <strong>and</strong> define<br />

by describing, comparing, classifying, <strong>and</strong> giving examples.<br />

• Identifying <strong>the</strong> steps in a process <strong>and</strong> showing how each step relates to<br />

<strong>the</strong> overall process. Describe how something should be done or how<br />

something typically happens.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 306<br />

306<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

CRITICAL THINKING<br />

Students sometimes think<br />

that “critical thinking” is<br />

something that only teachers<br />

or expert writers do. Be<br />

sure to explain to students<br />

that <strong>the</strong> focus <strong>of</strong> this chapter<br />

is on analysis, which is<br />

at <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> critical<br />

thinking. Defining key<br />

terms, explaining <strong>the</strong> steps<br />

in a process, <strong>and</strong> analyzing<br />

causes <strong>and</strong> effects are essential<br />

to thinking critically<br />

<strong>and</strong> productively about any<br />

topic.<br />

Explaining what: Definition<br />

example<br />

Explaining why: Effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> projection<br />

Explaining how: <strong>the</strong><br />

process <strong>of</strong> freeing ourselves<br />

from dependency<br />

• Describing causes <strong>and</strong> effects <strong>and</strong> showing why certain causes lead to<br />

specific effects. Analyze how several causes lead to a single effect, or show<br />

how a single cause leads to multiple effects.<br />

• Supporting explanations with specific evidence. Use descriptions, examples,<br />

comparisons, analogies, images, facts, data, or statistics to show what,<br />

how, or why.<br />

In Spirit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Valley: Androgyny <strong>and</strong> Chinese Thought, psychologist Sukie Colgrave<br />

illustrates many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se techniques as she explains an important concept from<br />

psychology: <strong>the</strong> phenomenon <strong>of</strong> projection. Colgrave explains how we “project” attributes<br />

missing in our own personality onto ano<strong>the</strong>r person—especially someone we<br />

love:<br />

A one-sided development <strong>of</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> masculine or feminine principles has<br />

[an] unfortunate consequence for our psychological <strong>and</strong> intellectual health:<br />

it encourages <strong>the</strong> phenomenon termed “projection.” This is <strong>the</strong> process by<br />

which we project onto o<strong>the</strong>r people, things, or ideologies, those aspects <strong>of</strong><br />

ourselves which we have not, for whatever reason, acknowledged or developed.<br />

The most familiar example <strong>of</strong> this is <strong>the</strong> obsession which usually accompanies<br />

being “in love.” A person whose feminine side is unrealised will<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten “fall in love” with <strong>the</strong> feminine which she or he “sees” in ano<strong>the</strong>r person,<br />

<strong>and</strong> similarly with <strong>the</strong> masculine. The experience <strong>of</strong> being “in love” is<br />

one <strong>of</strong> powerful dependency. As long as <strong>the</strong> projection appears to fit its object<br />

nothing awakens <strong>the</strong> person to <strong>the</strong> reality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> projection. But sooner<br />

or later <strong>the</strong> lover usually becomes aware <strong>of</strong> certain discrepancies between her<br />

or his desires <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> person chosen to satisfy <strong>the</strong>m. Resentment, disappointment,<br />

anger <strong>and</strong> rejection rapidly follow, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>the</strong> relationship disintegrates....But<br />

if we can explore our own psyches we may discover what<br />

it is we were dem<strong>and</strong>ing from our lover <strong>and</strong> start to develop it in ourselves.<br />

The moment this happens we begin to see o<strong>the</strong>r people a little more clearly.<br />

We are freed from some <strong>of</strong> our needs to make o<strong>the</strong>rs what we want <strong>the</strong>m<br />

to be, <strong>and</strong> can begin to love <strong>the</strong>m more for what <strong>the</strong>y are.<br />

EXPLAINING WHAT<br />

Explaining what something is or means requires showing <strong>the</strong> relationship between<br />

it <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> class <strong>of</strong> beings, objects, or concepts to which it belongs. Formal definition,<br />

which is <strong>of</strong>ten essential in explaining, has three parts: <strong>the</strong> thing or term to be defined,<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 307<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

307<br />

<strong>the</strong> class, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> distinguishing characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> thing or term. The thing being<br />

defined can be concrete, such as a turkey, or abstract, such as democracy.<br />

THING OR TERM CLASS DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS<br />

A turkey is a bird that has brownish plumage <strong>and</strong> a bare,<br />

wattled head <strong>and</strong> neck; it is widely<br />

domesticated for food.<br />

Democracy is government by <strong>the</strong> people, exercised directly or<br />

through elected representatives.<br />

Frequently, writers use extended definitions when <strong>the</strong>y need to give more than a<br />

mere formal definition. An extended definition may explain <strong>the</strong> word’s etymology<br />

or historical roots, describe sensory characteristics <strong>of</strong> something (how it looks, feels,<br />

sounds, tastes, smells), identify its parts, indicate how something is used, explain<br />

what it is not, provide an example <strong>of</strong> it, <strong>and</strong>/or note similarities or differences between<br />

this term <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r words or things.<br />

The following extended definition <strong>of</strong> democracy, written for an audience <strong>of</strong> college<br />

students to appear in a textbook, begins with <strong>the</strong> etymology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> word <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n<br />

explains—using analysis, comparison, example, <strong>and</strong> description—what democracy is<br />

<strong>and</strong> what it is not:<br />

TEACHING TIP<br />

Ask students to annotate<br />

<strong>the</strong> various techniques for<br />

extended definition illustrated<br />

in this paragraph on<br />

democracy. Their marginal<br />

notes might be as follows:<br />

Since democracy is government <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people, by <strong>the</strong> people, <strong>and</strong> for <strong>the</strong><br />

people, a democratic form <strong>of</strong> government is not fixed or static. Democracy<br />

is dynamic; it adapts to <strong>the</strong> wishes <strong>and</strong> needs <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people. The term<br />

democracy derives from <strong>the</strong> Greek word demos, meaning “<strong>the</strong> common people,”<br />

<strong>and</strong> -kratia, meaning “strength or power” used to govern or rule.<br />

Democracy is based on <strong>the</strong> notion that a majority <strong>of</strong> people creates laws <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>n everyone agrees to abide by those laws in <strong>the</strong> interest <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> common<br />

good. In a democracy, people are not ruled by a king, a dictator, or a small<br />

group <strong>of</strong> powerful individuals. Instead, people elect <strong>of</strong>ficials who use <strong>the</strong><br />

power temporarily granted to <strong>the</strong>m to govern <strong>the</strong> society. For example, <strong>the</strong><br />

people may agree that <strong>the</strong>ir government should raise money for defense, so<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficials levy taxes to support an army. If enough people decide, however,<br />

that taxes for defense are too high, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>y request that <strong>the</strong>ir elected<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficials change <strong>the</strong> laws or <strong>the</strong>y elect new <strong>of</strong>ficials. The essence <strong>of</strong> democracy<br />

lies in its responsiveness: Democracy is a form <strong>of</strong> government in which<br />

laws <strong>and</strong> lawmakers change as <strong>the</strong> will <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> majority changes.<br />

Formal definition<br />

Description: What<br />

democracy is<br />

Etymology: Analysis <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> word’s roots<br />

Comparison: What<br />

democracy is not<br />

Example<br />

Formal definition<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 308<br />

308<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

Figurative expressions—vivid word pictures using similes, metaphors, or analogies—can<br />

also explain what something is. During World War II, for example, <strong>the</strong><br />

Writer’s War Board asked E. B. White (author <strong>of</strong> Charlotte’s Web <strong>and</strong> many New<br />

Yorker magazine essays, as well as o<strong>the</strong>r works) to provide an explanation <strong>of</strong> democracy.<br />

Instead <strong>of</strong> giving a formal definition or etymology, White responded with a<br />

series <strong>of</strong> imaginative comparisons showing <strong>the</strong> relationship between various parts <strong>of</strong><br />

American culture <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> concept <strong>of</strong> democracy:<br />

Surely <strong>the</strong> Board knows what democracy is. It is <strong>the</strong> line that forms on <strong>the</strong><br />

right. It is <strong>the</strong> don’t in Don’t Shove. It is <strong>the</strong> hole in <strong>the</strong> stuffed shirt through<br />

which <strong>the</strong> sawdust slowly trickles; it is <strong>the</strong> dent in <strong>the</strong> high hat. Democracy<br />

is <strong>the</strong> recurrent suspicion that more than half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people are right more<br />

than half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> time. It is <strong>the</strong> feeling <strong>of</strong> privacy in <strong>the</strong> voting booths, <strong>the</strong><br />

feeling <strong>of</strong> communion in <strong>the</strong> libraries, <strong>the</strong> feeling <strong>of</strong> vitality everywhere.<br />

Democracy is <strong>the</strong> score at <strong>the</strong> beginning <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ninth. It is an idea which<br />

hasn’t been disproved yet, a song <strong>the</strong> words <strong>of</strong> which have not gone bad. It’s<br />

<strong>the</strong> mustard on <strong>the</strong> hot dog <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> cream in <strong>the</strong> rationed c<strong>of</strong>fee. Democracy<br />

is a request from a War Board, in <strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> a morning in <strong>the</strong> middle<br />

<strong>of</strong> a war, wanting to know what democracy is.<br />

Often, we think that explanations <strong>of</strong> technical subjects must be academic <strong>and</strong> complex,<br />

but sometimes writers about technical subjects use images <strong>and</strong> metaphors to get<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir point across. In <strong>the</strong> following definition <strong>of</strong> Web robots—so-called “bots,” Andrew<br />

Leonard, writing for a contemporary audience in Wired magazine, enlivens his<br />

explanation by personifying <strong>the</strong>se s<strong>of</strong>tware programs:<br />

Web robots—spiders, w<strong>and</strong>erers, <strong>and</strong> worms. Cancelbots, Lazarus, <strong>and</strong> Automoose.<br />

Chatterbots, s<strong>of</strong>t bots, userbots, taskbots, knowbots, <strong>and</strong> mailbots.<br />

. . . In current online parlance, <strong>the</strong> word “bot” pops up everywhere,<br />

flung around carelessly to describe just about any kind <strong>of</strong> computer program—a<br />

logon script, a spellchecker—that performs a task on a network.<br />

Strictly speaking, all bots are “autonomous”—able to react to <strong>the</strong>ir environments<br />

<strong>and</strong> make decisions without prompting from <strong>the</strong>ir creators; while<br />

<strong>the</strong> master or mistress is brewing c<strong>of</strong>fee, <strong>the</strong> bot is <strong>of</strong>f retrieving Web documents,<br />

exploring a MUD, or combatting Usenet spam. ...Even more<br />

important than function is behavior—bona fide bots are programs with<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 309<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

309<br />

personality. Real bots talk, make jokes, have feelings—even if those feelings<br />

are nothing more than cleverly conceived algorithms.<br />

EXPLAINING HOW<br />

Explaining how something should be done or how something happens is usually<br />

called process analysis. One kind <strong>of</strong> process analysis is <strong>the</strong> “how-to” explanation: how<br />

to cook a turkey, how to tune an engine, how to get a job. Such recipes or directions<br />

are prescriptive: You typically explain how something should be done. In a second<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> process analysis, you explain how something happens or is typically done—<br />

without being directive or prescriptive. In a descriptive process analysis, you explain<br />

how some natural or social process typically happens: how cells split during mitosis,<br />

how hailstones form in a cloud, how students react to <strong>the</strong> pressure <strong>of</strong> examinations,<br />

or how political c<strong>and</strong>idates create <strong>the</strong>ir public images. In both prescriptive <strong>and</strong><br />

descriptive explanations, however, you are analyzing a process—dividing <strong>the</strong> sequence<br />

into its parts or steps—<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n showing how <strong>the</strong> parts contribute to <strong>the</strong> whole<br />

process.<br />

Cookbooks, automobile-repair manuals, instructions for assembling toys or appliances,<br />

<strong>and</strong> self-improvement books are all examples <strong>of</strong> prescriptive process analysis.<br />

Writers <strong>of</strong> recipes, for example, begin with analyses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ingredients <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

steps in preparing <strong>the</strong> food. Then <strong>the</strong>y carefully explain how <strong>the</strong> steps are related, how<br />

to avoid problems, <strong>and</strong> how to serve mouth-watering concoctions. Farley Mowat, naturalist<br />

<strong>and</strong> author <strong>of</strong> Never Cry Wolf, gives his readers <strong>the</strong> following detailed—<strong>and</strong><br />

humorous—recipe for creamed mouse. Mowat became interested in this recipe when<br />

he decided to test <strong>the</strong> nutritional content <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wolf ’s diet. “In <strong>the</strong> event that any<br />

<strong>of</strong> my readers may be interested in personally exploiting this hi<strong>the</strong>rto overlooked<br />

source <strong>of</strong> excellent animal protein,” Mowat writes, “I give <strong>the</strong> recipe in full”:<br />

TEACHING TIP<br />

Explain that process analysis<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten contains two kinds<br />

<strong>of</strong> analyses: analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

ingredients, parts, or items<br />

used in <strong>the</strong> process <strong>and</strong><br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> chronology.<br />

In a recipe, for example, <strong>the</strong><br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> parts occurs in<br />

<strong>the</strong> list <strong>of</strong> ingredients; <strong>the</strong><br />

chronology is <strong>the</strong> instructions.<br />

Ask students to read<br />

<strong>the</strong> Mowat <strong>and</strong> Thomas<br />

excerpts for both kinds <strong>of</strong><br />

analyses. Then ask <strong>the</strong>m to<br />

apply both kinds <strong>of</strong> analyses,<br />

if appropriate, to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

own topics or drafts.<br />

INGREDIENTS:<br />

Souris à la Crème<br />

One dozen fat mice Salt <strong>and</strong> pepper One cup white flour<br />

Cloves One piece sowbelly Ethyl alcohol<br />

Skin <strong>and</strong> gut <strong>the</strong> mice, but do not remove <strong>the</strong> heads; wash, <strong>the</strong>n place in a<br />

pot with enough alcohol to cover <strong>the</strong> carcasses. Allow to marinate for about<br />

two hours. Cut sowbelly into small cubes <strong>and</strong> fry slowly until most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

fat has been rendered. Now remove <strong>the</strong> carcasses from <strong>the</strong> alcohol <strong>and</strong> roll<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 310<br />

310<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

<strong>the</strong>m in a mixture <strong>of</strong> salt, pepper <strong>and</strong> flour; <strong>the</strong>n place in frying pan <strong>and</strong><br />

sauté for about five minutes (being careful not to allow <strong>the</strong> pan to get too<br />

hot, or <strong>the</strong> delicate meat will dry out <strong>and</strong> become tough <strong>and</strong> stringy). Now<br />

add a cup <strong>of</strong> alcohol <strong>and</strong> six or eight cloves. Cover <strong>the</strong> pan <strong>and</strong> allow to<br />

simmer slowly for fifteen minutes. The cream sauce can be made according<br />

to any st<strong>and</strong>ard recipe. When <strong>the</strong> sauce is ready, drench <strong>the</strong> carcasses<br />

with it, cover <strong>and</strong> allow to rest in a warm place for ten minutes <strong>before</strong><br />

serving.<br />

CRITICAL READING<br />

Show students how writers<br />

use multiple strategies by<br />

asking <strong>the</strong>m to identify<br />

rhetorical strategies that<br />

Thomas uses in this excerpt.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> margins, have<br />

students identify at least<br />

one example to illustrate<br />

definition, process, <strong>and</strong><br />

causal strategies. If possible,<br />

connect this exercise to<br />

<strong>the</strong> students’ own writing.<br />

Model identification <strong>of</strong><br />

strategies with your own<br />

draft or with a sample piece<br />

<strong>of</strong> student writing. Then<br />

have students trade drafts<br />

or notes <strong>and</strong> have peer<br />

readers suggest how <strong>the</strong><br />

writer may combine several<br />

explaining strategies.<br />

Explaining how something happens or is typically done involves a descriptive<br />

process analysis. It requires showing <strong>the</strong> chronological relationship between one<br />

idea, event, or phenomenon <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> next—<strong>and</strong> it depends on close observation. In<br />

The Lives <strong>of</strong> a Cell, biologist <strong>and</strong> physician Lewis Thomas explains that ants are like<br />

humans: while <strong>the</strong>y are individuals, <strong>the</strong>y can also act toge<strong>the</strong>r to create a social organism.<br />

Although exactly how ants communicate remains a mystery,Thomas explains<br />

how <strong>the</strong>y combine to form a thinking, working organism:<br />

[Ants] seem to live two kinds <strong>of</strong> lives: <strong>the</strong>y are individuals, going about <strong>the</strong><br />

day’s business without much evidence <strong>of</strong> thought for tomorrow, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>y<br />

are at <strong>the</strong> same time component parts, cellular elements, in <strong>the</strong> huge,<br />

writhing, ruminating organism <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill, <strong>the</strong> nest, <strong>the</strong> hive. . . .<br />

A solitary ant, afield, cannot be considered to have much <strong>of</strong> anything<br />

on his mind; indeed, with only a few neurons strung toge<strong>the</strong>r by fibers,<br />

he can’t be imagined to have a mind at all, much less a thought. He is<br />

more like a ganglion on legs. Four ants toge<strong>the</strong>r, or ten, encircling a<br />

dead moth on a path, begin to look more like an idea. They fumble <strong>and</strong><br />

shove, gradually moving <strong>the</strong> food toward <strong>the</strong> Hill, but as though by blind<br />

chance. It is only when you watch <strong>the</strong> dense mass <strong>of</strong> thous<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> ants,<br />

crowded toge<strong>the</strong>r around <strong>the</strong> Hill, blackening <strong>the</strong> ground, that you begin<br />

to see <strong>the</strong> whole beast, <strong>and</strong> now you observe it thinking, planning, calculating.<br />

It is an intelligence, a kind <strong>of</strong> live computer, with crawling bits for<br />

its wits.<br />

At a stage in <strong>the</strong> construction, twigs <strong>of</strong> a certain size are needed, <strong>and</strong><br />

all <strong>the</strong> members forage obsessively for twigs <strong>of</strong> just this size. Later, when<br />

outer walls are to be finished, thatched, <strong>the</strong> size must change, <strong>and</strong> as though<br />

given new orders by telephone, all <strong>the</strong> workers shift <strong>the</strong> search to <strong>the</strong> new<br />

twigs. If you disturb <strong>the</strong> arrangement <strong>of</strong> a part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Hill, hundreds <strong>of</strong> ants<br />

will set it vibrating, shifting, until it is put right again. Distant sources <strong>of</strong><br />

food are somehow sensed, <strong>and</strong> long lines, like tentacles, reach out over <strong>the</strong><br />

ground, up over walls, behind boulders, to fetch it in.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 311<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

311<br />

EXPLAINING WHY<br />

“Why?” may be <strong>the</strong> question most commonly asked by human beings. We are fascinated<br />

by <strong>the</strong> reasons for everything that we experience in life. We ask questions<br />

about natural phenomena: Why is <strong>the</strong> sky blue? Why does a teakettle whistle? Why<br />

do some materials act as superconductors? We also find human attitudes <strong>and</strong> behavior<br />

intriguing: Why is chocolate so popular? Why do some people hit small<br />

lea<strong>the</strong>r balls with big sticks <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n run around a field stomping on little white pillows?<br />

Why are America’s family farms economically depressed? Why did <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States go to war in Iraq? Why is <strong>the</strong> Internet so popular?<br />

Explaining why something occurs can be <strong>the</strong> most fascinating—<strong>and</strong> difficult—<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> expository writing. Answering <strong>the</strong> question “why” usually requires analyzing<br />

cause-<strong>and</strong>-effect relationships. The causes, however, may be too complex or<br />

intangible to identify precisely. We are on comparatively secure ground when we ask<br />

why about physical phenomena that can be weighed, measured, <strong>and</strong> replicated under<br />

laboratory conditions. Under those conditions, we can determine cause <strong>and</strong> effect<br />

with precision.<br />

Fire, for example, has three necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes: combustible material,<br />

oxygen, <strong>and</strong> ignition temperature. Without each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se causes, fire will not<br />

occur (each cause is “necessary”); taken toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>se three causes are enough to<br />

cause fire (all three toge<strong>the</strong>r are “sufficient”). In this case, <strong>the</strong> cause-<strong>and</strong>-effect relationship<br />

can be illustrated by an equation:<br />

CAUSE 1 + CAUSE 2 + CAUSE 3 = EFFECT<br />

(combustible (oxygen) (ignition (fire)<br />

material)<br />

temperature)<br />

Analyzing both necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes is essential to explaining an effect.<br />

You may say, for example, that wind shear (an abrupt downdraft in a storm)<br />

“caused” an airplane crash. In fact, wind shear may have contributed (been necessary)<br />

to <strong>the</strong> crash but was not by itself <strong>the</strong> total (sufficient) cause <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> crash: an airplane<br />

with enough power may be able to overcome wind shear forces in certain circumstances.<br />

An explanation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> crash is not complete until you analyze <strong>the</strong> full range<br />

<strong>of</strong> necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes, which may include wind shear, lack <strong>of</strong> power, mechanical<br />

failure, <strong>and</strong> even pilot error.<br />

Sometimes, explanations for physical phenomena are beyond our analytical powers.<br />

Astrophysicists, for example, have good <strong>the</strong>oretical reasons for believing that<br />

WRITE TO LEARN<br />

Write-to-learn activities<br />

don’t have to be connected<br />

to a specific reading or text<br />

assignment. Any time you<br />

are giving instructions or<br />

discussing a point <strong>and</strong> hear<br />

yourself saying, “Does<br />

everyone underst<strong>and</strong> that?”<br />

or “Does anyone have a<br />

question?” stop <strong>and</strong> give<br />

students one or two minutes<br />

to write down <strong>the</strong><br />

main point <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> discussion<br />

or to write down two<br />

questions about it. Such<br />

write-to-learn activities<br />

give every student a chance<br />

to respond actively <strong>and</strong> give<br />

feedback to <strong>the</strong> teacher<br />

about students’ questions<br />

<strong>and</strong> ideas.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 312<br />

312<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

black holes cause gigantic gravitational whirlpools in outer space, but <strong>the</strong>y have difficulty<br />

explaining why black holes exist—or whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y exist at all.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> realm <strong>of</strong> human cause <strong>and</strong> effect, determining causes <strong>and</strong> effects can be<br />

as tricky as explaining why black holes exist. Why, for example, do some children learn<br />

math easily while o<strong>the</strong>rs fail? What effect does failing at math have on a child? What<br />

are necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes for divorce? What are <strong>the</strong> effects <strong>of</strong> divorce on parents<br />

<strong>and</strong> children? Although you may not be able to explain all <strong>the</strong> causes or effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> something, you should not be satisfied until you have considered a wide range <strong>of</strong><br />

possible causes <strong>and</strong> effects. Even <strong>the</strong>n, you need to qualify or modify your statements,<br />

using such words as might, usually, <strong>of</strong>ten, seldom, many, or most, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n giving<br />

as much support <strong>and</strong> evidence as you can.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> following paragraphs, Jonathan Kozol, a critic <strong>of</strong> America’s educational<br />

system <strong>and</strong> author <strong>of</strong> Illiterate America, explains <strong>the</strong> multiple effects <strong>of</strong> a single cause:<br />

illiteracy. Kozol supports his explanation by citing specific ways that illiteracy affects<br />

<strong>the</strong> lives <strong>of</strong> people:<br />

Illiterates cannot read <strong>the</strong> menu in a restaurant.<br />

They cannot read <strong>the</strong> cost <strong>of</strong> items on <strong>the</strong> menu in <strong>the</strong> window <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

restaurant <strong>before</strong> <strong>the</strong>y enter.<br />

Illiterates cannot read <strong>the</strong> letters that <strong>the</strong>ir children bring home from<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir teachers. They cannot study school department circulars that tell <strong>the</strong>m<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> courses that <strong>the</strong>ir children must be taking if <strong>the</strong>y hope to pass <strong>the</strong><br />

SAT exams. They cannot help with homework. They cannot write a letter<br />

to <strong>the</strong> teacher. They are afraid to visit in <strong>the</strong> classroom. They do not want<br />

to humiliate <strong>the</strong>ir child or <strong>the</strong>mselves. . . .<br />

Many illiterates cannot read <strong>the</strong> admonition on a pack <strong>of</strong> cigarettes.<br />

Nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> Surgeon General’s warning nor its reproduction on <strong>the</strong> package<br />

can alert <strong>the</strong>m to <strong>the</strong> risks. Although most people learn by word <strong>of</strong><br />

mouth that smoking is related to a number <strong>of</strong> grave physical disorders, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

do not get <strong>the</strong> chance to read <strong>the</strong> detailed stories which can document this<br />

danger with <strong>the</strong> vividness that turns concern into determination to resist.<br />

They can see <strong>the</strong> h<strong>and</strong>some cowboy or <strong>the</strong> slim Virginia lady lighting up a<br />

filter cigarette; <strong>the</strong>y cannot heed <strong>the</strong> words that tell <strong>the</strong>m that this product<br />

is (not “may be”) dangerous to <strong>the</strong>ir health. Sixty million men <strong>and</strong> women<br />

are condemned to be <strong>the</strong> unalerted, high-risk c<strong>and</strong>idates for cancer....<br />

Illiterates cannot travel freely. When <strong>the</strong>y attempt to do so, <strong>the</strong>y encounter<br />

risks that few <strong>of</strong> us can dream <strong>of</strong>. They cannot read traffic signs <strong>and</strong>,<br />

while <strong>the</strong>y <strong>of</strong>ten learn to recognize <strong>and</strong> to decipher symbols, <strong>the</strong>y cannot<br />

manage street names which <strong>the</strong>y haven’t seen <strong>before</strong>. The same is true for<br />

bus <strong>and</strong> subway stops. While ingenuity can sometimes help a man or<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 313<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

313<br />

woman to discern directions from familiar l<strong>and</strong>marks, buildings, cemeteries,<br />

churches, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> like, most illiterates are virtually immobilized. They<br />

seldom w<strong>and</strong>er past <strong>the</strong> streets <strong>and</strong> neighborhoods <strong>the</strong>y know. Geographical<br />

paralysis becomes a bitter metaphor for <strong>the</strong>ir entire existence. They are<br />

immobilized in almost every sense we can imagine. They can’t move up.<br />

They can’t move out. They cannot see beyond.<br />

Warming Up: Journal Exercises<br />

The following exercises will help you practice writing explanations. Read all <strong>of</strong><br />

t <strong>the</strong> following exercises <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n write on <strong>the</strong> three that interest you most.<br />

If ano<strong>the</strong>r idea occurs to you, write about it.<br />

1. Write a one-paragraph explanation <strong>of</strong> an idea, term, or concept that you<br />

have discussed in a class that you are currently taking. From biology, for example,<br />

you might define photosyn<strong>the</strong>sis or gene splicing. From psychology, you<br />

might define psychosis or projection. From computer studies, you might define<br />

cyberspace or morphing. First, identify someone who might need to<br />

know about this subject. Then give a definition <strong>and</strong> an illustration. Finally,<br />

describe how <strong>the</strong> term was discovered or invented, what its effects or applications<br />

are, <strong>and</strong>/or how it works.<br />

2. Imitating E. B. White’s short “definition” <strong>of</strong> democracy, use imaginative<br />

comparisons to write a short definition—serious or humorous—<strong>of</strong> one <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> following words: freedom, adolescence, ma<strong>the</strong>matics, politicians, parents,<br />

misery, higher education, luck, or a word <strong>of</strong> your own choice.<br />

3. Novelist Ernest Hemingway once defined courage as “grace under pressure.”<br />

Using this definition, explain how you or someone you know showed this<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> courage in a difficult situation.<br />

4. When asked what jazz is, Louis Armstrong replied, “Man, if you gotta ask<br />

you’ll never know.” If you know quite a bit about jazz, explain what Armstrong<br />

meant. Or choose a familiar subject to which <strong>the</strong> same remark might<br />

apply. What can be “explained” about that subject, <strong>and</strong> what cannot?<br />

5. Choose a skill that you’ve acquired (for example, playing a musical instrument,<br />

operating a machine, playing a sport, drawing, counseling o<strong>the</strong>rs, driving<br />

in rush-hour traffic, dieting) <strong>and</strong> explain to a novice how he or she can<br />

acquire that skill. Reread what you’ve written. Then write ano<strong>the</strong>r version<br />

addressed to an expert. What parts can you leave out? What must you add?<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 314<br />

314<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

6. Sometimes writers use st<strong>and</strong>ard definitions to explain a key term, but sometimes<br />

<strong>the</strong>y need to resist conventional definition in order to make a point.<br />

LaMer Steptoe, an eleventh-grader in West Philadelphia, was faced with a<br />

form requiring her to check her racial identity. Like many Americans <strong>of</strong> multicultural<br />

heritage, she decided not to check one box. In <strong>the</strong> following paragraphs,<br />

reprinted from National Public Radio’s All Things Considered, Ms.<br />

Steptoe explains how she decided to (re)define herself. As you read her response,<br />

consider how you might need to resist a conventional definition in<br />

your own explaining essay.<br />

Multiracialness<br />

Caucasian, African-American, Latin American, Asian-American.<br />

Check one. I look black, so I’ll pick that one. But, no, wait, if I pick<br />

that, I’ll be denying <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r sides <strong>of</strong> my family. So I’ll pick white. But<br />

I’m not white or black, I’m both, <strong>and</strong> part Native American, too. It’s<br />

confusing when you have to pick which race to identify with, especially<br />

when you have family who, on one side, ask, “Why do you talk like a<br />

white girl?” when, in <strong>the</strong> eyes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r side <strong>of</strong> your family, your<br />

behind is black.<br />

I never met my dad’s mom, my gr<strong>and</strong>mo<strong>the</strong>r, Maybelle Dawson Boyd<br />

Steptoe, <strong>and</strong> my fa<strong>the</strong>r never knew his fa<strong>the</strong>r. But my aunts or uncles<br />

or cousins all think <strong>of</strong> me as black or white. I mean, I’m not <strong>the</strong><br />

lightest-skinned person, but my cousins down South swear I’m white.<br />

It bo<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>and</strong> that bo<strong>the</strong>rs me, how people could care so much<br />

about your skin color.<br />

My mo<strong>the</strong>r’s mo<strong>the</strong>r, Sylvia Gabriel, lives in Connecticut, near where<br />

my aunt, uncle <strong>and</strong> cousins on that side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> family live. Now, <strong>the</strong>y’re<br />

white, <strong>and</strong> where my gr<strong>and</strong>ma lives, <strong>the</strong>re are very few black people<br />

or people <strong>of</strong> color. And when we visit, people look at us a lot, staring<br />

like, “What is that woman doing with those people?” It shocks <strong>the</strong><br />

heck out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m when my bro<strong>the</strong>r <strong>and</strong> I call her Gr<strong>and</strong>ma.<br />

My mo<strong>the</strong>r’s side is Italian. I really didn’t get any Italian culture except<br />

for <strong>the</strong> food. My fa<strong>the</strong>r was raised much differently from my<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r. My fa<strong>the</strong>r is superstitious; he believes that a child should<br />

know his or her place <strong>and</strong> not speak unless spoken to. My fa<strong>the</strong>r is very<br />

much into both his African-American <strong>and</strong> Native American heritage.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 315<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

315<br />

Multiracialness is a very tricky subject for my fa<strong>the</strong>r. He’ll tell people that<br />

I’m Native, African-American <strong>and</strong> Caucasian American, but at <strong>the</strong><br />

same time he’ll say things like, “Listen to jazz, listen to your cultural<br />

music.” He says,“LaMer, look in <strong>the</strong> mirror. You’re black. Ask any white<br />

person: <strong>the</strong>y’ll say you’re black.” He doesn’t get it. I really would ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

be colorless than to pick a race. I like o<strong>the</strong>r music, not just black music.<br />

The term African-American bugs me. I’m not African. I’m American<br />

as a hot dog. We should have friends who are yellow, red, blue, black,<br />

purple, gay, religious, bisexual, trilingual, whatever, so you don’t have<br />

a stereotypical view. I’ve met mean people <strong>and</strong> nice people <strong>of</strong> all different<br />

backgrounds. At my school, I grew up with all <strong>the</strong>se kids, <strong>and</strong><br />

I didn’t look at <strong>the</strong>m as white or Jewish or heterosexual; I looked at<br />

<strong>the</strong>m as, “Oh, she’s funny, he’s sweet.”<br />

I know what box I’m going to choose. I pick D for none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> above,<br />

because my race is human.<br />

Lange, Doro<strong>the</strong>a, photographer, “Migrant Agricultural Worker’s Family.” February<br />

1936. America from <strong>the</strong> Great Depression to World War II: Black-<strong>and</strong>-White Photographs<br />

from <strong>the</strong> FSA-OWI, 1935–1945, Library <strong>of</strong> Congress.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 316<br />

316<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

7. Use your explaining skills to analyze visual images. For example, <strong>the</strong> work <strong>of</strong><br />

art that opens this chapter is Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s 1788 portrait <strong>of</strong><br />

Marie Antoinette <strong>and</strong> her Children. Use your browser to search for information<br />

about Marie Antoinette, her role in <strong>the</strong> <strong>French</strong> <strong>Revolution</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

career <strong>of</strong> Vigée-Lebrun. Then study <strong>the</strong> photograph on <strong>the</strong> previous page <strong>of</strong><br />

a migrant woman <strong>and</strong> her children, taken in California in 1936. Do some<br />

Internet research on Doro<strong>the</strong>a Lange <strong>and</strong> her series <strong>of</strong> photographs <strong>of</strong> migrant<br />

workers in California. Write an essay comparing <strong>and</strong> contrasting <strong>the</strong><br />

artists (Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun <strong>and</strong> Doro<strong>the</strong>a Lange), <strong>the</strong> composition <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>se two images, <strong>and</strong>/or <strong>the</strong> social/cultural conditions surrounding each<br />

image. Assume that your audience is a group <strong>of</strong> your peers in your composition<br />

class.<br />

PROFESSIONAL WRITING<br />

Miss Clairol’s “Does She . . .<br />

Or Doesn’t She?”:<br />

How to Advertise a<br />

Dangerous Product<br />

James B. Twitchell<br />

A longtime pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> English at <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Florida, James B. Twitchell<br />

has written a dozen books on a variety <strong>of</strong> academic <strong>and</strong> cultural topics. His recent<br />

books on advertising <strong>and</strong> popular culture include Carnival Culture: The<br />

Trashing <strong>of</strong> Taste in America (1992), Adcult USA: The Triumph <strong>of</strong> Advertising<br />

in American Culture (1996), <strong>and</strong> Living It Up: Our Love Affair<br />

with Luxury (2002). In “Miss Clairol’s ‘Does She ...Or Doesn’t She?’ ” taken<br />

from Twenty Ads That Shook <strong>the</strong> World (2000), Twitchell examines <strong>the</strong> Miss<br />

Clairol advertising campaign, which was designed by Shirley Polyk<strong>of</strong>f. Twitchell<br />

explains how Polyk<strong>of</strong>f ’s ads, which ran for nearly twenty years, revolutionized<br />

<strong>the</strong> hair-coloring industry. Part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> success <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ad was in <strong>the</strong> catchy title,<br />

Twitchell notes, but equally important were <strong>the</strong> children in <strong>the</strong> ads <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> followup<br />

phrase, “Hair color so natural, only her hairdresser knows for sure.” (Before you<br />

read Twitchell’s essay, however, look at several <strong>of</strong> Polyk<strong>of</strong>f ’s Clairol ads by searching<br />

Shirley Polyk<strong>of</strong>f on Google.)<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE<br />

1

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 317<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

317<br />

Two types <strong>of</strong> product are difficult to advertise: <strong>the</strong> very common <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> very<br />

radical. Common products, called “parity products,” need contrived distinctions<br />

to set <strong>the</strong>m apart. You announce <strong>the</strong>m as “New <strong>and</strong> Improved, Bigger<br />

<strong>and</strong> Better.” But singular products need <strong>the</strong> illusion <strong>of</strong> acceptability. They<br />

have to appear as if <strong>the</strong>y were not new <strong>and</strong> big, but old <strong>and</strong> small.<br />

So, in <strong>the</strong> 1950s, new objects like television sets were designed to look<br />

like furniture so that <strong>the</strong>y would look “at home” in your living room. Meanwhile,<br />

accepted objects like automobiles were growing massive tail fins to<br />

make <strong>the</strong>m seem bigger <strong>and</strong> better, new <strong>and</strong> improved.<br />

Although hair coloring is now very common (about half <strong>of</strong> all American<br />

women between <strong>the</strong> ages <strong>of</strong> thirteen <strong>and</strong> seventy color <strong>the</strong>ir hair, <strong>and</strong><br />

about one in eight American males between thirteen <strong>and</strong> seventy does <strong>the</strong><br />

same), such was certainly not <strong>the</strong> case generations ago. The only women<br />

who regularly dyed <strong>the</strong>ir hair were actresses like Jean Harlow, <strong>and</strong> “fast<br />

women,” most especially prostitutes. The only man who dyed his hair was<br />

Gorgeous George, <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional wrestler. He was also <strong>the</strong> only man to<br />

use perfume.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> twentieth century, prostitutes have had a central role in developing<br />

cosmetics. For <strong>the</strong>m, sexiness is an occupational necessity, <strong>and</strong> hence<br />

anything that makes <strong>the</strong>m look young, flushed, <strong>and</strong> fertile is quickly assimilated.<br />

Creating a full-lipped, big-eyed, <strong>and</strong> rosy-cheeked image is <strong>the</strong><br />

basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lipstick, eye shadow, mascara, <strong>and</strong> rouge industries. While fashion<br />

may come down from <strong>the</strong> couturiers, face paint comes up from <strong>the</strong><br />

street. Yesterday’s painted woman is today’s fashion plate.<br />

In <strong>the</strong> 1950s, just as Betty Friedan was sitting down to write The Feminine<br />

Mystique, <strong>the</strong>re were three things a lady should not do. She should not<br />

smoke in public, she should not wear long pants (unless under an overcoat),<br />

<strong>and</strong> she should not color her hair. Better she should pull out each<br />

gray str<strong>and</strong> by its root than risk association with those who bleached or,<br />

worse, dyed <strong>the</strong>ir hair.<br />

This was <strong>the</strong> cultural context into which Lawrence M. Gelb, a chemical<br />

broker <strong>and</strong> enthusiastic entrepreneur, presented his product to Foote,<br />

Cone & Belding. Gelb had purchased <strong>the</strong> rights to a <strong>French</strong> hair-coloring<br />

process called Clairol. The process was unique in that unlike o<strong>the</strong>r available<br />

hair-coloring products, which coated <strong>the</strong> hair, Clairol actually penetrated<br />

<strong>the</strong> hair shaft, producing s<strong>of</strong>ter, more natural tones. Moreover, it contained<br />

a foamy shampoo base <strong>and</strong> mild oils that cleaned <strong>and</strong> conditioned <strong>the</strong> hair.<br />

When <strong>the</strong> product was first introduced during World War II, <strong>the</strong><br />

application process took five different steps <strong>and</strong> lasted a few hours. The<br />

2<br />

3<br />

4<br />

5<br />

6<br />

7<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 318<br />

318<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

TEACHING TIP<br />

Twitchell does a good job<br />

<strong>of</strong> analyzing <strong>the</strong> historical<br />

<strong>and</strong> cultural forces at work<br />

behind <strong>the</strong> Miss Clairol<br />

ads. Have students also<br />

practice analyzing <strong>the</strong><br />

composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> visual<br />

images in <strong>the</strong> Clairol ads<br />

on <strong>the</strong> Polyk<strong>of</strong>f Web site.<br />

Specifically, how does <strong>the</strong><br />

composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> images<br />

support (or add additional<br />

information to) Twitchell’s<br />

<strong>the</strong>sis that <strong>the</strong> Polyk<strong>of</strong>f<br />

campaign successfully<br />

managed <strong>the</strong> problems <strong>of</strong> a<br />

“dangerous product” being<br />

advertised to a complex<br />

audience?<br />

users were urban <strong>and</strong> wealthy. In 1950, <strong>after</strong> seven years <strong>of</strong> research <strong>and</strong><br />

development, Gelb once again took <strong>the</strong> beauty industry by storm. He introduced<br />

<strong>the</strong> new Miss Clairol Hair Color Bath, a single-step haircoloring<br />

process.<br />

This product, unlike any haircolor previously available, lightened, darkened,<br />

or changed a woman’s natural haircolor by coloring <strong>and</strong> shampooing<br />

hair in one simple step that took only twenty minutes. Color results were<br />

more natural than anything you could find at <strong>the</strong> corner beauty parlor. It<br />

was hard to believe. Miss Clairol was so technologically advanced that<br />

demonstrations had to be done onstage at <strong>the</strong> International Beauty Show,<br />

using buckets <strong>of</strong> water, to prove to <strong>the</strong> industry that it was not a hoax. This<br />

breakthrough was almost too revolutionary to sell.<br />

In fact, within six months <strong>of</strong> Miss Clairol’s introduction, <strong>the</strong> number<br />

<strong>of</strong> women who visited <strong>the</strong> salon for permanent hair-coloring services increased<br />

by more than 500 percent! The women still didn’t think <strong>the</strong>y could<br />

do it <strong>the</strong>mselves. And Good Housekeeping magazine rejected hair-color advertising<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y too didn’t believe <strong>the</strong> product would work. The magazine<br />

waited for three years <strong>before</strong> finally reversing its decision, accepting<br />

<strong>the</strong> ads, <strong>and</strong> awarding Miss Clairol’s new product <strong>the</strong> “Good Housekeeping<br />

Seal <strong>of</strong> Approval.”<br />

FC&B passed <strong>the</strong> “Yes you can do it at home” assignment to Shirley<br />

Polyk<strong>of</strong>f, a zesty <strong>and</strong> genial first-generation American in her late twenties.<br />

She was, as she herself was <strong>the</strong> first to admit, a little unsophisticated, but<br />

her colleagues thought she understood how women would respond to abrupt<br />

change. Polyk<strong>of</strong>f understood emotion, all right, <strong>and</strong> she also knew that you<br />

could be outrageous if you did it in <strong>the</strong> right context. You can be very<br />

naughty if you are first perceived as being nice. Or, in her words, “Think it<br />

out square, say it with flair.” And it is just this reconciliation <strong>of</strong> opposites<br />

that informs her most famous ad.<br />

She knew this almost from <strong>the</strong> start. On July 9, 1955, Polyk<strong>of</strong>f wrote<br />

to <strong>the</strong> head art director that she had three campaigns for Miss Clairol Hair<br />

Color Bath. The first shows <strong>the</strong> same model in each ad, but with slightly<br />

different hair color. The second exhorts “Tear up those baby pictures! You’re<br />

a redhead now,” <strong>and</strong> plays on <strong>the</strong> American desire to refashion <strong>the</strong> self by<br />

rewriting history. These two ideas were, as she says, “knock-downs” en route<br />

to what she really wanted. In her autobiography, appropriately titled Does<br />

She ...Or Doesn’t She?: And How She Did It, Polyk<strong>of</strong>f explains <strong>the</strong> third execution,<br />

<strong>the</strong> one that will work:<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 319<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

319<br />

#3. Now here’s <strong>the</strong> one I really want. If I can get it sold to <strong>the</strong> client.<br />

Listen to this: “Does she ...or doesn’t she?” (No, I’m not kidding. Didn’t<br />

you ever hear <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> arresting question?) Followed by: “Only her mo<strong>the</strong>r<br />

knows for sure!” or “So natural, only her mo<strong>the</strong>r knows for sure!”<br />

I may not do <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r part, though as far as I’m concerned<br />

mo<strong>the</strong>r is <strong>the</strong> ultimate authority. However, if Clairol goes retail, <strong>the</strong>y<br />

may have a problem <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>fending beauty salons, where <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

presently doing all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir business. So I may change <strong>the</strong> word<br />

“mo<strong>the</strong>r” to “hairdresser.” This could be awfully good business—turning<br />

<strong>the</strong> hairdresser into a color expert. Besides, it reinforces <strong>the</strong> claim<br />

<strong>of</strong> naturalness, <strong>and</strong> not so incidentally, glamorizes <strong>the</strong> salon.<br />

The psychology is obvious. I know from myself. If anyone admires<br />

my hair, I’d ra<strong>the</strong>r die than admit I dye. And since I feel so<br />

strongly that <strong>the</strong> average woman is me, this great stress on naturalness<br />

is important [Polyk<strong>of</strong>f 1975, 28–29].<br />

While her headline is naughty, <strong>the</strong> picture is nice <strong>and</strong> natural. Exactly<br />

what “Does She . . . or Doesn’t She” do? To men <strong>the</strong> answer was clearly sexual,<br />

but to women it certainly was not. The male editors <strong>of</strong> Life magazine<br />

balked about running this headline until <strong>the</strong>y did a survey <strong>and</strong> found out<br />

women were not filling in <strong>the</strong> ellipsis <strong>the</strong> way <strong>the</strong>y were.<br />

Women, as Polyk<strong>of</strong>f knew, were finding different meaning because<br />

<strong>the</strong>y were actually looking at <strong>the</strong> model <strong>and</strong> her child. For <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> picture<br />

was not presexual but postsexual, not inviting male attention but expressing<br />

satisfaction with <strong>the</strong> result. Miss Clairol is a mo<strong>the</strong>r, not a love interest.<br />

If that is so, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> product must be misnamed: it should be Mrs.<br />

Clairol. Remember, this was <strong>the</strong> mid-1950s, when illegitimacy was a powerful<br />

taboo. Out-<strong>of</strong>-wedlock children were still called bastards, not love<br />

children. This ad was far more dangerous than anything Benetton or Calvin<br />

Klein has ever imagined.<br />

The naught/nice conundrum was fur<strong>the</strong>r intensified <strong>and</strong> diffused by<br />

some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ads featuring a wedding ring on <strong>the</strong> model’s left h<strong>and</strong>. Although<br />

FC&B experimented with models purporting to be secretaries,<br />

schoolteachers, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> like, <strong>the</strong> motif <strong>of</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r <strong>and</strong> child was always constant.<br />

So what was <strong>the</strong> answer to what she does or doesn’t do? To women,<br />

what she did had to do with visiting <strong>the</strong> hairdresser. Of course, men couldn’t<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

15<br />

16<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 320<br />

320<br />

Chapter 7<br />

explaining<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>. This was <strong>the</strong> world <strong>before</strong> unisex hair care. Men still went<br />

to barber shops. This was <strong>the</strong> same pre-feminist generation in which <strong>the</strong><br />

solitary headline “Modess . . . because” worked magic selling female sanitary<br />

products. The ellipsis masked a knowing implication that excluded<br />

men. That was part <strong>of</strong> its attraction. Women know, men don’t. This youjust-don’t-get-it<br />

motif was to become a central marketing strategy as <strong>the</strong><br />

women’s movement was aided <strong>and</strong> exploited by Madison Avenue<br />

nichemeisters.<br />

Polyk<strong>of</strong>f had to be ambiguous for ano<strong>the</strong>r reason. As she notes in her<br />

memo, Clairol did not want to be obvious about what <strong>the</strong>y were doing to<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir primary customer—<strong>the</strong> beauty shop. Remember that <strong>the</strong> initial product<br />

entailed five different steps performed by <strong>the</strong> hairdresser, <strong>and</strong> lasted<br />

hours. Many women were still using hairdressers for something <strong>the</strong>y could<br />

now do by <strong>the</strong>mselves. It did not take a detective to see that <strong>the</strong> company<br />

was trying to run around <strong>the</strong> beauty shop <strong>and</strong> sell to <strong>the</strong> end-user. So <strong>the</strong><br />

ad again has it both ways. The hairdresser is invoked as <strong>the</strong> expert—only<br />

he knows for sure—but <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> coloring your hair can be done without<br />

his expensive assistance.<br />

The copy block on <strong>the</strong> left <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> finished ad reasserts this intimacy,<br />

only now it is not <strong>the</strong> hairdresser speaking, but ano<strong>the</strong>r woman who has used<br />

<strong>the</strong> product. The emphasis is always on returning to young <strong>and</strong> radiant hair,<br />

hair you used to have, hair, in fact, that glistens exactly like your current<br />

companion’s—your child’s hair.<br />

The copy block on <strong>the</strong> right is all business <strong>and</strong> was never changed<br />

during <strong>the</strong> campaign. The process <strong>of</strong> coloring is always referred to as<br />

“automatic color tinting.” Automatic was to <strong>the</strong> fifties what plastic became<br />

to <strong>the</strong> sixties, <strong>and</strong> what networking is today. Just as your food was kept<br />

automatically fresh in <strong>the</strong> refrigerator, your car had an automatic transmission,<br />

your house had an automatic <strong>the</strong>rmostat, your dishes <strong>and</strong> clo<strong>the</strong>s<br />

were automatically cleaned <strong>and</strong> dried, so, too, your hair had automatic<br />

tinting.<br />

However, what is really automatic about hair coloring is that once you<br />

start, you won’t stop. Hair grows, roots show, buy more product . . . automatically.<br />

The genius <strong>of</strong> Gillette was not just that <strong>the</strong>y sold <strong>the</strong> “safety<br />

razor” (<strong>the</strong>y could give <strong>the</strong> razor away), but that <strong>the</strong>y also sold <strong>the</strong> concept<br />

<strong>of</strong> being clean-shaven. Clean-shaven means that you use <strong>the</strong>ir blade every<br />

day, so, <strong>of</strong> course, you always need more blades. Clairol made “roots showing”<br />

into what Gillette had made “five o’clock shadow.”<br />

17<br />

18<br />

19<br />

20<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:58 AM Page 321<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

321<br />

As was to become typical in hair-coloring ads, <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> model was<br />

a good ten years younger than <strong>the</strong> typical product user. The model is in her<br />

early thirties (witness <strong>the</strong> age <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> child), too young to have gray hair.<br />

This aspirational motif was picked up later for o<strong>the</strong>r Clairol products:<br />

“If I’ve only one life . . . let me live it as a blonde!” “Every woman should<br />

be a redhead . . . at least once in her life!” “What would your husb<strong>and</strong> say<br />

if suddenly you looked 10 years younger?” “Is it true blondes have more<br />

fun?” “What does he look at second?” And, <strong>of</strong> course, “The closer he gets<br />

<strong>the</strong> better you look!”<br />

But <strong>the</strong>se slogans for different br<strong>and</strong> extensions only work because<br />

Miss Clairol had done her job. She made hair coloring possible, she made<br />

hair coloring acceptable, she made at-home hair coloring—dare I say it—<br />

empowering. She made <strong>the</strong> unique into <strong>the</strong> commonplace. By <strong>the</strong> 1980s,<br />

<strong>the</strong> hairdresser problem had been long forgotten <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> follow-up lines<br />

read, “Hair color so natural, <strong>the</strong>y’ll never know for sure.”<br />

The Clairol <strong>the</strong>me propelled sales 413 percent higher in six years <strong>and</strong><br />

influenced nearly 50 percent <strong>of</strong> all adult women to tint <strong>the</strong>ir tresses. Ironically,<br />

Miss Clairol, bought out by Bristol-Myers in 1959, also politely<br />

opened <strong>the</strong> door to her competitors, L’Oreal <strong>and</strong> Revlon.<br />

Thanks to Clairol, hair coloring has become a very attractive business<br />

indeed. The key ingredients are just a few pennies’ worth <strong>of</strong> peroxide, ammonia,<br />

<strong>and</strong> pigment. In a pretty package at <strong>the</strong> drugstore it sells for four to<br />