A prolific painter of portraits before and after the French Revolution ...

A prolific painter of portraits before and after the French Revolution ...

A prolific painter of portraits before and after the French Revolution ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ch07.qxd 12/2/04 11:57 AM Page 311<br />

techniques for explaining<br />

311<br />

EXPLAINING WHY<br />

“Why?” may be <strong>the</strong> question most commonly asked by human beings. We are fascinated<br />

by <strong>the</strong> reasons for everything that we experience in life. We ask questions<br />

about natural phenomena: Why is <strong>the</strong> sky blue? Why does a teakettle whistle? Why<br />

do some materials act as superconductors? We also find human attitudes <strong>and</strong> behavior<br />

intriguing: Why is chocolate so popular? Why do some people hit small<br />

lea<strong>the</strong>r balls with big sticks <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>n run around a field stomping on little white pillows?<br />

Why are America’s family farms economically depressed? Why did <strong>the</strong> United<br />

States go to war in Iraq? Why is <strong>the</strong> Internet so popular?<br />

Explaining why something occurs can be <strong>the</strong> most fascinating—<strong>and</strong> difficult—<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> expository writing. Answering <strong>the</strong> question “why” usually requires analyzing<br />

cause-<strong>and</strong>-effect relationships. The causes, however, may be too complex or<br />

intangible to identify precisely. We are on comparatively secure ground when we ask<br />

why about physical phenomena that can be weighed, measured, <strong>and</strong> replicated under<br />

laboratory conditions. Under those conditions, we can determine cause <strong>and</strong> effect<br />

with precision.<br />

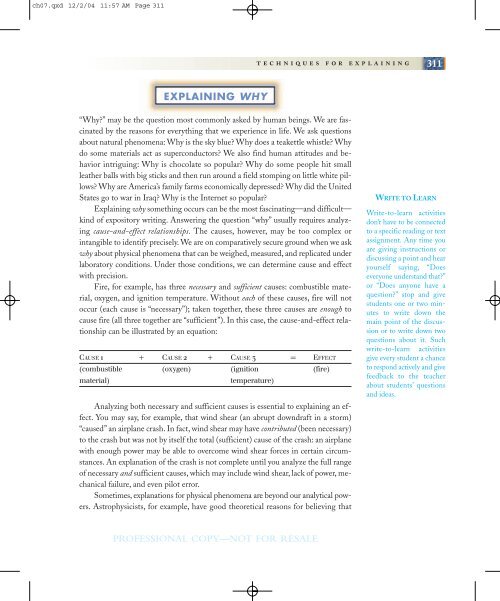

Fire, for example, has three necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes: combustible material,<br />

oxygen, <strong>and</strong> ignition temperature. Without each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se causes, fire will not<br />

occur (each cause is “necessary”); taken toge<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>se three causes are enough to<br />

cause fire (all three toge<strong>the</strong>r are “sufficient”). In this case, <strong>the</strong> cause-<strong>and</strong>-effect relationship<br />

can be illustrated by an equation:<br />

CAUSE 1 + CAUSE 2 + CAUSE 3 = EFFECT<br />

(combustible (oxygen) (ignition (fire)<br />

material)<br />

temperature)<br />

Analyzing both necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes is essential to explaining an effect.<br />

You may say, for example, that wind shear (an abrupt downdraft in a storm)<br />

“caused” an airplane crash. In fact, wind shear may have contributed (been necessary)<br />

to <strong>the</strong> crash but was not by itself <strong>the</strong> total (sufficient) cause <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> crash: an airplane<br />

with enough power may be able to overcome wind shear forces in certain circumstances.<br />

An explanation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> crash is not complete until you analyze <strong>the</strong> full range<br />

<strong>of</strong> necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient causes, which may include wind shear, lack <strong>of</strong> power, mechanical<br />

failure, <strong>and</strong> even pilot error.<br />

Sometimes, explanations for physical phenomena are beyond our analytical powers.<br />

Astrophysicists, for example, have good <strong>the</strong>oretical reasons for believing that<br />

WRITE TO LEARN<br />

Write-to-learn activities<br />

don’t have to be connected<br />

to a specific reading or text<br />

assignment. Any time you<br />

are giving instructions or<br />

discussing a point <strong>and</strong> hear<br />

yourself saying, “Does<br />

everyone underst<strong>and</strong> that?”<br />

or “Does anyone have a<br />

question?” stop <strong>and</strong> give<br />

students one or two minutes<br />

to write down <strong>the</strong><br />

main point <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> discussion<br />

or to write down two<br />

questions about it. Such<br />

write-to-learn activities<br />

give every student a chance<br />

to respond actively <strong>and</strong> give<br />

feedback to <strong>the</strong> teacher<br />

about students’ questions<br />

<strong>and</strong> ideas.<br />

PROFESSIONAL COPY—NOT FOR RESALE