Urban Design Guide - Section 2 Enhance and ... - Islington Council

Urban Design Guide - Section 2 Enhance and ... - Islington Council

Urban Design Guide - Section 2 Enhance and ... - Islington Council

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

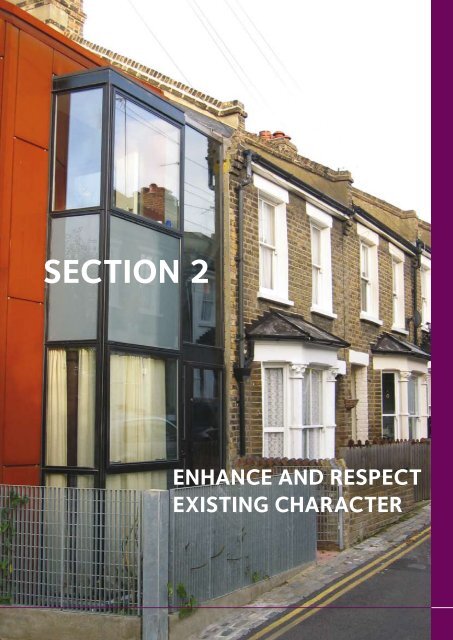

SECTION 2<br />

ENHANCE AND RESPECT<br />

EXISTING CHARACTER

2.1 CONTEXT AND LOCAL DISTINCTIVENESS<br />

Highbury Place – new houses have been<br />

adjoined to the grade 2 listed Georgian<br />

terrace <strong>and</strong> created compositional unity by<br />

careful replication of the proportions <strong>and</strong><br />

details of the existing buildings.<br />

On the right is a fine example of a<br />

contemporary terrace that fits harmoniously<br />

opposite an Edwardian terrace of similar scale<br />

<strong>and</strong> proportions.<br />

2.1 Context And Local<br />

Distinctiveness<br />

Much of <strong>Islington</strong> benefits from a rich streetbased<br />

urban fabric both inside <strong>and</strong> outside<br />

conservation areas. New buildings should<br />

reinforce this character by creating an<br />

appropriate <strong>and</strong> durable fit that harmonise<br />

with their setting. They should create a scale<br />

<strong>and</strong> form of development that is appropriate<br />

in relation to the existing built form so that it<br />

provides a consistent / coherent setting for<br />

the space or street that it defines or encloses,<br />

while also enhancing <strong>and</strong> complementing the<br />

local identity of an area.<br />

The nature of the existing street frontage will<br />

therefore normally determine the extent of<br />

potential development.<br />

“The character of townscape depends<br />

on how individual buildings contribute to<br />

a harmonious whole, through relating to<br />

the scale of their neighbours <strong>and</strong> creating<br />

a continuous urban form”. (DETR - ‘By<br />

<strong>Design</strong>’, p21)<br />

Within this context, high quality<br />

contemporary designs will be supported,<br />

except in uniform terraces where exact<br />

replication may be required for the sake of<br />

compositional unity. Contemporary designs<br />

can be used in historically sensitive areas<br />

– nevertheless extra care needs to be taken:<br />

the scheme should be of an extremely<br />

high st<strong>and</strong>ard <strong>and</strong> designed from a strong<br />

underst<strong>and</strong>ing of the surrounding context.<br />

Pastiche design that is a poor copy of the<br />

original design will generally be resisted.<br />

“New <strong>and</strong> old buildings can coexist happily<br />

without disguising one as the other, if the<br />

design of the new is a response to urban<br />

design objectives”. (DETR - ‘By <strong>Design</strong>’,<br />

p19)<br />

All new buildings will need to respond<br />

appropriately to the existing frontage <strong>and</strong><br />

normally follow the established building line<br />

18 <strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

(refer to section 3.2 – Building Lines). In areas<br />

that have lost their original street pattern <strong>and</strong><br />

character, street based redevelopment will<br />

often be required to knit the area back with<br />

the surrounding street pattern.<br />

Buildings that st<strong>and</strong> out because they fail to<br />

conform with these st<strong>and</strong>ards will only be<br />

acceptable in exceptional circumstances (refer<br />

to 1.1.2, 2.2.3 <strong>and</strong> 3.2.5).<br />

“A building should only st<strong>and</strong> out from<br />

the background of buildings if it<br />

contributes positively to views <strong>and</strong><br />

vistas as a l<strong>and</strong>mark. Buildings which<br />

have functions of civic importance are<br />

one example”. (DETR - ‘By <strong>Design</strong>’, p21)<br />

Further detailed guidance <strong>and</strong> policy on<br />

buildings within conservation areas is<br />

provided by Conservation Area <strong>Design</strong><br />

<strong>Guide</strong>lines <strong>and</strong> section 12.3 of the UDP.<br />

Compton Rd - a Victorian terrace (left) sits<br />

opposite a weak pastiche. (right)<br />

2.1 CONTEXT AND LOCAL DISTINCTIVENESS<br />

A pastiche design that has none of the<br />

refinement of the adjacent late Victorian<br />

terrace.<br />

This infill (on the right)is not entirely faithful to<br />

the existing building but it nevertheless<br />

re-establishes the lost half of a Victorian semi<br />

detached house.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

19

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

Union Chapel soars above Compton Terrace - an<br />

important <strong>and</strong> appropriate local l<strong>and</strong>mark.<br />

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

2.2.1 Background<br />

During the post-war period, parts of<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> like many other places in Britain<br />

suffered from unsympathetic<br />

redevelopment. The harmony, character <strong>and</strong><br />

order of the street-based environment, was<br />

undermined by uneven <strong>and</strong> comprehensive<br />

development. Nevertheless, subtle variation<br />

in height <strong>and</strong> form can sometimes add<br />

interest, particularly where it has evolved<br />

over a number of years. Before 1939 where<br />

bigger variations occurred, this appropriately<br />

reflected the relative public importance of<br />

buildings such as a church or town hall. Today,<br />

sharp differences between the scale of small<br />

buildings <strong>and</strong> large, out-of-scale monoliths<br />

have broken down the old building hierarchy,<br />

undermined the character of many areas<br />

<strong>and</strong> their sense of order. Where there is an<br />

opportunity to address this they should be<br />

corrected. The Building Heights Advice Note,<br />

nevertheless defines specific areas within<br />

the borough where buildings that exceed 30<br />

metres can be located subject to a number of<br />

criteria.<br />

2.2.2 Overall Criteria<br />

Street frontages with a consistent roofline<br />

<strong>and</strong> facades are generally sensitive to<br />

alteration <strong>and</strong> there will normally be a<br />

presumption against change (refer to section<br />

2.4). There is usually more scope for change<br />

in the roofline <strong>and</strong> facades within streets<br />

with a variety of frontages / building heights,<br />

particularly where the height of frontages is<br />

relatively low in proportion to the width of<br />

the street.<br />

This tower block has no respect for the original<br />

height, scale or street line.<br />

20<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

This building was seamlessly extended from two to<br />

three storeys <strong>and</strong> now responds better to the scale<br />

of its immediate neighbours.<br />

An opportunity for significantly extending the<br />

height of a street frontage - a more consistent<br />

building line <strong>and</strong> the extra enclosure would help<br />

define the street.<br />

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

Upper Street - the subtle variation in height is given underlying order by its narrow plot widths - any change<br />

to the roofline might undermine its harmony <strong>and</strong> human scale. The N1 shopping centre (foreground) has been<br />

successfully inserted by respecting this arrangement.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

21

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

A sensitive intervention that marginally rises<br />

above its neighbours at a bend in the road.<br />

Example of uneven development - this<br />

block has no respect for the height, scale<br />

or proportions of the uniform terrace or the<br />

topography.<br />

However, variations in building heights, do<br />

not in itself provide a justification for height<br />

increases. An alteration or extension to the<br />

existing roofline may still be unacceptable in<br />

the following circumstances:<br />

• Where the existing street frontages <strong>and</strong><br />

roof profile have historical <strong>and</strong> / or<br />

architectural importance <strong>and</strong> / or<br />

contribute to an area’s individual<br />

character. This will include listed buildings,<br />

conservation areas <strong>and</strong> sometimes other<br />

buildings that do not have this status.<br />

• Where the alteration to a façade or<br />

roofline impacts adversely upon the<br />

architectural integrity <strong>and</strong> quality of the<br />

existing or neighbouring buildings.<br />

• Where a change to the roofline or façade<br />

would be out of scale with its neighbours,<br />

especially if it starts to inappropriately<br />

dominate the street, <strong>and</strong> undermines the<br />

rhythm of the street frontage.<br />

• Where change adversely impacts on views<br />

<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong>marks.<br />

• Where it impacts adversely on the<br />

topography of the street.<br />

• Where it causes a canyon effect <strong>and</strong> / or<br />

unduly overshadows the street.<br />

• Where it impacts adversely on the<br />

character of an open space or the public<br />

realm.<br />

• Where it creates an imbalance in height<br />

between opposite sides of the street. This<br />

may not be relevant where there is<br />

potential future scope for the<br />

redevelopment of the opposite side too,<br />

or on wide streets.<br />

The two sides of the street are unbalanced.<br />

22<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

2.2.3 Views <strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong>marks<br />

General Principles<br />

The scope for high buildings including<br />

buildings that rise above 30 metres <strong>and</strong> larger<br />

street frontages are covered in the Building<br />

Heights Advice Note. The IUDG deals with<br />

general principles <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ards.<br />

As set out in section 12.2 of the UDP, the<br />

<strong>Council</strong> will protect <strong>and</strong> enhance strategic <strong>and</strong><br />

local views of strategic <strong>and</strong> local l<strong>and</strong>marks.<br />

Any building which blocks or detracts from<br />

important or potentially important views, will<br />

be resisted.<br />

Notwithst<strong>and</strong>ing the above, a building<br />

that st<strong>and</strong>s out can sometimes contribute<br />

positively to the urban environment by:<br />

• Becoming a focal point.<br />

• Providing an element of surprise or<br />

contrast.<br />

• Reinforcing a sense of place.<br />

• Highlighting the importance of a public<br />

building.<br />

This may provide a justification for a building<br />

that, contrasts with its neighbours or, more<br />

occasionally, rises above its neighbours.<br />

It will nevertheless need to be a special<br />

building that is suitably located <strong>and</strong> designed<br />

to an exceptional st<strong>and</strong>ard that embodies<br />

an integrity that is carried through all its<br />

elevations. It must also respond to its<br />

surrounding threshold (refer to section 3).<br />

The Union Chapel’s dominance is undermined<br />

by a nearby residential tower block.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong>’s most recent major l<strong>and</strong>mark.<br />

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

St James Church carefully framed by the<br />

buildings that front Clerkenwell Green.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

23

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

The verticality of a corner can be exaggerated<br />

without reliance on extra height.<br />

Great care needs to be taken with the design<br />

of corners. The impact of a poorly designed<br />

or detailed elevation becomes magnified on<br />

corners particularly if it is designed to be<br />

emphasised.<br />

Buildings do not have to be big to st<strong>and</strong> out.<br />

Corners are often best addressed by<br />

creative articulation rather than any<br />

height increase.<br />

24<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

Emphasising Junctions<br />

It is sometimes appropriate to have a focal<br />

point that announces or reinforces a place<br />

or closes a view. Closing a view at the<br />

junction of streets can heighten the role of<br />

architecture in giving character to space <strong>and</strong><br />

provide an element of anticipation.<br />

It is often appropriate to emphasise a corner,<br />

particularly at an important junction. This is<br />

usually best achieved by exaggerating the<br />

vertical proportions of a façade through<br />

clever articulating devices, for example by:<br />

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

• Curving the frontage.<br />

• Wrapping the fenestration around the<br />

corner.<br />

• Terminating the roof differently.<br />

It is sometimes appropriate to provide<br />

further punctuation by raising the height of<br />

the corner marginally above the prevailing<br />

height to reinforce the importance of a<br />

junction. Where extra height is proposed it<br />

should be contained so that it does not spill<br />

further down the street frontage, otherwise<br />

the punctuation will become diluted <strong>and</strong><br />

the coherence of the rest of the frontage<br />

undermined; in other words the punctuation<br />

of the junction should be a ‘full stop’ <strong>and</strong> not<br />

‘part of the sentence’.<br />

1 City Road occupies a prominent corner.<br />

As well as closing the view, it also lines up<br />

with the centre line of Moorgate for which it<br />

provides a defining l<strong>and</strong>mark.<br />

© Crown copyright. All rights reserved. London Borough of <strong>Islington</strong> LA100021551 2007.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

25

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

Consistent height <strong>and</strong> building form <strong>and</strong><br />

height on both sides of a new street<br />

provides balance <strong>and</strong> a good consistent<br />

backdrop that gives the street coherence<br />

<strong>and</strong> an appropriate sense of enclosure.<br />

2.2.4 Comprehensive<br />

Redevelopment<br />

On a large site where there is an opportunity<br />

for comprehensive redevelopment with<br />

new streets <strong>and</strong> spaces created, there may<br />

be scope to incorporate street frontages,<br />

within the centre of the development that<br />

are marginally higher than the existing area.<br />

Where the new development meets existing<br />

streets or street frontages it will still normally<br />

need to conform with the height of the<br />

neighbouring or adjoining terrace <strong>and</strong> will<br />

therefore need to be considered in terms of<br />

the above criteria in section 2.2.<br />

New schemes often work most satisfactorily<br />

where the height <strong>and</strong> building form is<br />

consistent along each new street frontage,<br />

so that they read in terms of the rhythm<br />

of the frontage <strong>and</strong> as a backdrop to the<br />

space or street they define, <strong>and</strong> do not draw<br />

too much attention. A variation of building<br />

height can contribute towards a fragmented<br />

environment. Most notably when individual<br />

buildings inappropriately dominate, or are<br />

too monolithic in appearance, such as that<br />

occurred in many 1960’s developments.<br />

(Refer also to 3.2.4 Practical Application of<br />

the Perimeter Block Layout).<br />

Parts of <strong>Islington</strong> have suffered from<br />

uneven <strong>and</strong> fragmented development that<br />

undermines the coherence of the spaces<br />

between buildings.<br />

A variation of buildings<br />

can contribute towards a<br />

fragmented environment,<br />

particularly when individual<br />

buildings inappropriately<br />

dominate or are too<br />

monolithic in appearance,<br />

such as occurred in many<br />

1960’s developments.<br />

26<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

2.2.5 Height to Width Ratios<br />

General Principles<br />

Building height also needs to be considered in<br />

terms of its proportion in relation to the size<br />

of the space it defines / encloses. The height<br />

of a street frontage should provide sufficient<br />

sense of enclosure, natural surveillance <strong>and</strong><br />

maximise the potential development<br />

opportunity of a site.<br />

Most of <strong>Islington</strong>’s Victorian residential<br />

terraced streets have a height-to-width ratio<br />

of between 0.5 to 1 <strong>and</strong> 0.7 to 1. Streets<br />

with a ratio of between 0.5 to 1 <strong>and</strong> 1 to 1<br />

normally provide a well proportioned street<br />

frontage which provides a good sense of<br />

enclosure.<br />

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

Streets with Frontages that Exceed their<br />

Width<br />

Schemes where the height exceeds the<br />

width of the street will not normally be<br />

acceptable if they cause a canyon effect<br />

<strong>and</strong> inhibit sufficient light <strong>and</strong> air reaching<br />

the buildings <strong>and</strong> street below, unless they<br />

can be justified in terms of adding to local<br />

distinctiveness. Nevertheless there may be<br />

more scope on those streets with a north-tosouth<br />

orientation as they normally allow more<br />

sunlight to permeate than streets with an<br />

east-to-west axis.<br />

The height of street frontages should normally be in<br />

proportion to the width of the street they define<br />

(Image from ‘By <strong>Design</strong>’)<br />

The south of the borough, <strong>and</strong> some of the<br />

other older parts of <strong>Islington</strong>, were originally<br />

characterised by a dense network of streets<br />

<strong>and</strong> alleys where the heights of building<br />

frontages often exceeded the width. High<br />

sided frontages along comparatively narrow<br />

streets will therefore normally be acceptable<br />

where they contribute towards maintaining<br />

the existing character of the area.<br />

– Deep narrow street typical of 18th <strong>and</strong> 19thC<br />

in the south of the borough<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

27

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

Westbourne Rd looking south from Bride St<br />

junction - 0.7 to 1 ratio provides strong<br />

enclosure that does not undermine amenity.<br />

Westbourne Rd looking north from Bride<br />

St junction- enclosure is weakened by the<br />

wider street, squat frontages <strong>and</strong> gaps<br />

between the end on houses.<br />

Low Frontages <strong>and</strong> Wide Streets<br />

Anything less than a 0.3 to 1 height to width<br />

ratio can result in streets, which suffer from<br />

too little enclosure where the buildings appear<br />

divorced from the street. This can sometimes<br />

be justified where the immediate context is<br />

characterised by this scale of buildings, <strong>and</strong><br />

where it contributes to local distinctiveness.<br />

Additional enclosure can often be provided by<br />

trees along the kerb edge or, in front gardens.<br />

Elsewhere, low frontages may appear<br />

inappropriately suburban in scale. They also<br />

may not maximise the development potential<br />

of the site or the natural surveillance<br />

opportunities.<br />

Exaggerating <strong>and</strong> Minimising the<br />

Apparent Height<br />

Sometimes there is a need to exaggerate or<br />

minimise the apparent height of a new<br />

development so that it accords with the<br />

context of the street. There are<br />

circumstances where the scale of<br />

development proposed is too small for its<br />

context. For example, the size of the frontage<br />

can sometimes be increased by generously<br />

extending the front face of the building above<br />

the top floor.<br />

Some of <strong>Islington</strong>’s main commercial streets such as Holloway Road are considerably wider than the height of<br />

the buildings that face them which sometimes provides scope for bigger frontages.<br />

28<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

Conversely, it can be necessary to keep the<br />

scale of the frontage to a minimum, especially<br />

along roads that are already rather narrow <strong>and</strong><br />

cavernous. This can sometimes be achieved<br />

by generously setting back the upper floors<br />

behind the front roof parapet so that it is not<br />

apparent from the street. Such a solution will<br />

also need to work in terms of its impact from<br />

longer views where it may be more visible. A<br />

ziggurat, or stepping back, approach was a<br />

common 1930’s <strong>and</strong> post-war solution. This<br />

approach will not normally be acceptable in<br />

streets with a uniform frontage (refer to 2.4).<br />

The use of monopitch or semi-barrel vault<br />

roofs can be used to emphasise or minimise<br />

height at the front or rear as appropriate.<br />

The scale of this frontage has been deliberately<br />

exaggerated by continuing the façade treatment<br />

above the top floor. The top line of openings appear<br />

like the windows below but they have no glass as<br />

they serve only the open roof terrace<br />

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

Natural light is maximised into this high sided narrow<br />

street by the use of a semi barrel vaulted roof<br />

While these Victorian frontages are modest in relation to the street width, this arrangement is the defining<br />

characteristic of the area.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

29

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

Despite being considerably bigger than its<br />

immediate neighbour, this building is more in scale<br />

with the rest of the City Road surrounds.<br />

Finsbury Square <strong>and</strong> surrounds - High frontages<br />

in relation to the street widths are consistent with<br />

their central location.<br />

The apparent height of the red brick building has been kept to a minimum by stepping the top two floors <strong>and</strong><br />

using recessive materials (glass <strong>and</strong> metal) so that it harmonises with the rhythm <strong>and</strong> scale of the existing street<br />

frontage.<br />

30<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

Relationship of Building Frontages with<br />

Open Spaces<br />

Where building frontages face onto public<br />

open spaces <strong>and</strong> squares, they should<br />

normally provide sufficient sense of enclosure<br />

<strong>and</strong> suitable backdrop to define <strong>and</strong> overlook<br />

the space while not over powering it.<br />

Open spaces can feel particularly threatening<br />

if they do not have an adequate level of<br />

natural surveillance from surrounding<br />

development. Nevertheless, the height should<br />

not be so great that they unduly dominate<br />

the space. Highbury Fields is a good example<br />

where this relationship works harmoniously.<br />

In contrast, King Square suffers from a<br />

fragmented <strong>and</strong> inconsistent frontage that<br />

contributes to the poor cohesion of the space<br />

itself <strong>and</strong> creates areas that are poorly<br />

enclosed with a lack of surveillance.<br />

19 th C King Sq as it was originally designed with a<br />

consistent height <strong>and</strong> edge that defined it (above)<br />

before it was demolished <strong>and</strong> rebuilt in the 1960’s.<br />

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

King Square today suffers from a poorly<br />

defined edge with a range of building<br />

sizes that contribute to undermine the<br />

coherence of the space.<br />

Highbury Fields - Georgian terrace<br />

provides an appropriately scaled backdrop.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

31

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

The horizontal slab front does not provide<br />

windows at second floor level; it is also at odds<br />

with the vertical organisation of its neighbours.<br />

The building on the left has little consideration<br />

of the vertical proportions, strong building line<br />

or formality of its Victorian neighbour.<br />

The coloured b<strong>and</strong>ing exaggerate the<br />

horizontal proportions of the library<br />

building, that fail to pick up the rhythm of<br />

the taller narrow frontages along the street.<br />

2.2.6 Rhythm, Scale <strong>and</strong><br />

Proportions<br />

Plot Widths <strong>and</strong> Vertical Proportions<br />

The scale of a building is also determined by<br />

its bulk <strong>and</strong> width <strong>and</strong> the manner in which<br />

the façade is articulated. Historically most of<br />

<strong>Islington</strong>’s street frontages are characterised<br />

by narrow plot widths where terraces are sub<br />

divided into plots where the height is greater<br />

than the width of the building. This<br />

contributes to the vertical proportions that<br />

underlie the human scale of pre-1939<br />

residential terraces <strong>and</strong> other street<br />

frontages. The vertical proportions are<br />

expressed both in the overall dimensions <strong>and</strong><br />

the individual elements, especially the<br />

fenestration, <strong>and</strong> the manner in which they<br />

are composed within the frontage. The<br />

repeated pattern of narrow street frontages<br />

creates a rhythm that also gives many of<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> streets both harmony <strong>and</strong><br />

coherence.<br />

High quality contemporary designs will<br />

normally be sought that are skillfully<br />

interwoven into their context, by<br />

incorporating the rhythm, scale <strong>and</strong><br />

proportions of the existing street frontage.<br />

The design should echo the narrow plot<br />

widths where this is the predominant building<br />

form in the surrounding area.<br />

Breaking down a long street frontage into<br />

a series of separate bays also helps avoid<br />

buildings appearing monolithic <strong>and</strong> provides<br />

them with a more human scale. Particularly<br />

with residential schemes, where there is an<br />

opportunity to create a whole new street<br />

frontage, consideration should be given to<br />

breaking down the frontage into a series of<br />

smaller frontages. This can be achieved by<br />

incorporating a contemporary reinterpretation<br />

of a terrace with a regular rhythm. Where<br />

it conforms to the configuration of its<br />

surrounds, this approach can also assist<br />

the integration of a comprehensive<br />

redevelopment.<br />

32<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

A fine contemporary terrace incorporating<br />

narrow plot widths / vertical proportions that<br />

achieve a regular rhythm through repetition.<br />

A recent extension to an existing two bay<br />

Victorian terrace - although some of the<br />

detailing is accurate, the window<br />

arrangement fails to pick up the existing<br />

rhythm of the terrace as the gaps between<br />

the window pairing is too great. The unsightly<br />

rainwater pipes further undermines the<br />

rhythm.<br />

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

A contemporary building frontage skillfully<br />

added to the end of a terrace.<br />

A playful variation of the existing street<br />

frontage that picks up the vertical proportions<br />

<strong>and</strong> rhythm of the rest of the frontage.<br />

Another example of a contemporary terrace which achieves a regular rhythm through repetition of its<br />

vertical elements. (Drawn by George Petrides, Agenda 21 Architects)<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

33

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

Fonthill Rd - the mansard roof continues<br />

without a break over two properties<br />

undermining the rhythm of the 2 bay frontages.<br />

Diespeker Wharf - Despite its strong roof line<br />

the vertical proportions still read through.<br />

In commercial streets which are characterised<br />

by larger buildings / longer street frontages,<br />

there is often more freedom to model the<br />

street frontages, particularly where the<br />

frontage is more heterogeneous.<br />

Nevertheless, consideration should also be<br />

given to how they work within the rhythm<br />

of the wider street frontage; they can also<br />

benefit from the use of vertical proportioning<br />

devices.<br />

Relationship of the Roofline <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Elevation<br />

Rooflines should normally respond to the<br />

articulation of the rest of the façade. It should<br />

normally be possible to read the width of the<br />

plot divisions from the bottom to the top of<br />

the building. The roofline should reflect the<br />

rhythm, harmony <strong>and</strong> scale of the longer<br />

street frontage. Stepped or sculptured<br />

rooflines can appear monolithic particularly<br />

where the shape of the roof does not pick up<br />

the sub division of the façade.<br />

2.2.7 Sloping Sites<br />

Stepped Rooflines <strong>and</strong> Frontages<br />

Street frontages that run down a hill should<br />

normally have a stepped roofline frontage <strong>and</strong><br />

threshold that echoes their topography <strong>and</strong><br />

allows the ground floor to synchronise with<br />

the footway <strong>and</strong> threshold space. Large blank<br />

flank walls at the junction between buildings<br />

should be avoided. Splitting residential<br />

buildings into narrower plot widths with a<br />

smaller number of flats of self contained<br />

service cores, also allow street frontages to<br />

step down a sloping street.<br />

The vertical proportions are undermined by<br />

the roof treatment that continues largely<br />

unbroken across the roof emphasising the<br />

buildings monolithic size.<br />

34<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

Modelling Long Building Frontages<br />

All new schemes must provide level access to<br />

meet the provisions of part M of the<br />

Building Regulations. Therefore some<br />

ingenuity is required where long building<br />

frontages with large floorplates are located on<br />

a slope. On steep hills, consideration should be<br />

given to incorporating entry points /<br />

frontages at different levels (as it steps down<br />

the slope) to allow the threshold, as well as<br />

the roofline to reflect the topography. In<br />

extreme circumstances, passenger lifts that<br />

stop at half levels sometimes provide the<br />

scope to break the floorplates. Alternatively,<br />

consideration can be given to modelling the<br />

roofline <strong>and</strong> frontage on a single floorplate<br />

building to suggest a step. Care nevertheless<br />

needs to be taken to ensure this is not at the<br />

expense of architectural integrity.<br />

Sloping site not reflected at the ground floor.<br />

2.2 HEIGHT AND SCALE<br />

All new schemes must<br />

provide level access to<br />

meet the provisions of<br />

part M of the Building<br />

Regulations.<br />

The middle building is too tall. It steps up<br />

too much not allowing a further step for<br />

the furthest building.<br />

Stepped frontage that follows the slope of<br />

the hill one plot at a time.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

35

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

A typical mid Victorian street frontage of<br />

individual houses, identified as vertically<br />

grouped paired windows that repeat in a rhythm.<br />

Too many small or identical windows with no<br />

underlying proportions or grouping framework<br />

can create an uninteresting facade <strong>and</strong> fail to<br />

break down the scale of a building.<br />

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

The architects of Georgian, Victorian <strong>and</strong><br />

Edwardian buildings took care to ensure the<br />

external form of the building created a<br />

suitable backdrop to the public realm. Modern<br />

building regulations <strong>and</strong> an underst<strong>and</strong>able<br />

desire to create comfortable living<br />

accommodation have focussed greater<br />

attention upon internal space st<strong>and</strong>ards<br />

<strong>and</strong> layout. It is important that this is not<br />

at the expense of the architectural quality<br />

of the elevations. The internal <strong>and</strong> the<br />

external requirements will always need to be<br />

reconciled. The street frontage must work in<br />

terms of its relationship to its neighbours <strong>and</strong><br />

in terms of its own architectural integrity.<br />

2.3.1 Windows<br />

The windows are a key component of the<br />

façade that help define a building’s character<br />

<strong>and</strong> provide underlying order as well as its<br />

overall proportions.<br />

Window Shape, Position <strong>and</strong> Sizes<br />

Care needs to be taken to ensure that the<br />

windows are of an appropriate scale to the<br />

façade <strong>and</strong> that each window in the façade<br />

has some relationship with each other. Key to<br />

this is identifying the appropriate shape,<br />

position <strong>and</strong> size of the windows.<br />

Some elevations can be unduly monotonous<br />

because of the number of repeated windows.<br />

The risk of this is greatest in large façades,<br />

particularly when small windows are used,<br />

where they can appear lost within the<br />

elevation.<br />

Too many different types of windows,<br />

particularly if they appear to have no<br />

apparent relationship to one another, can<br />

result in an untidy façade.<br />

Too many different types of windows <strong>and</strong><br />

treatments can create untidy <strong>and</strong> incoherent<br />

elevations.<br />

36<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

Repeated vertical grouping that defines<br />

plot width <strong>and</strong> creates underlying rhythm.<br />

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

Low floor to ceiling heights can generate<br />

squat proportions – in this case it disrupts<br />

the vertical proportions that characterise<br />

this terrace.<br />

The vertical proportions of the window<br />

openings are able to dominate because the<br />

horizontal b<strong>and</strong>ing is a subsidiary element.<br />

The continuous horizontal b<strong>and</strong>ing dominates<br />

this frontage. This <strong>and</strong> the single entrance<br />

results in a building that reads as a monolith.<br />

As well as the absence of a vertical ordering<br />

device, the lower floor-to-ceiling heights<br />

of the newer building on the right are made<br />

more obvious by the fact that the ground<br />

floor is appreciably lower than the Victorian<br />

frontage.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

37

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

Victorian <strong>and</strong> Georgian architects used symmetry,<br />

proportions <strong>and</strong> hierarchy to create a vertical<br />

window grouping.<br />

Contemporary buildings are usually characterised by<br />

lower floor to ceiling heights with little or no<br />

variation between each floor. This requires other<br />

strategies to achieve vertical articulation such as<br />

grouping windows into vertical b<strong>and</strong>s.<br />

Vertical Articulation (<strong>and</strong> addressing<br />

lower floor-to-ceiling heights)<br />

Articulating strategies should always be<br />

employed to provide street frontages with<br />

underlying order. The window arrangement is<br />

an important element in breaking down the<br />

scale of building frontages. For the reasons<br />

stated in 2.2.6, this is usually best achieved<br />

by emphasising the vertical proportions.<br />

Vertical proportions can be achieved by:<br />

• <strong>Design</strong>ing the windows so that their<br />

vertical axis is greater than the horizontal<br />

<strong>and</strong> / or dividing each window into a series<br />

of vertically proportioned glazing panels.<br />

Horizontally proportioned windows<br />

can sometimes be given more vertical<br />

emphasis by incorporating vertically<br />

proportioned glazing panels.<br />

• Grouping windows into vertical b<strong>and</strong>s<br />

that allow the fenestration to be read as a<br />

vertical grouping rather than a horizontal<br />

one. For example, Georgian <strong>and</strong> Victorian<br />

architects expressed individual terraced<br />

houses by pairing windows or grouping<br />

windows typically in a symmetrical<br />

arrangement. This usually involved<br />

employing geometric proportioning<br />

devices <strong>and</strong> a hierarchy that defined <strong>and</strong><br />

differentiated each floor by the graduation<br />

of the vertical height of the windows<br />

within an implied vertical grouping. Later<br />

Victorian <strong>and</strong> Edwardian buildings also<br />

used other devices such as the projecting<br />

bays <strong>and</strong> more elaborate decoration <strong>and</strong><br />

architraving.<br />

Lower floor-to-ceiling heights of modern<br />

houses can reduce the opportunity to<br />

graduate windows in this way, <strong>and</strong> can<br />

generate inappropriately squat or horizontally<br />

proportioned buildings <strong>and</strong> windows.<br />

38<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

The glazing bars of the UPVC replacement<br />

windows are so thick that they take up most<br />

of the window aperture.<br />

As well as the unsympathetic repainting, the<br />

metal replacement windows undermine the<br />

coherence <strong>and</strong> quality of this unusual frontage.<br />

The unsympathetic UPVC replacement windows<br />

are revealed by the outward tilt of the casement<br />

window as well as the fake glazing bars.<br />

The original crittal windows have suffered<br />

from an ad hoc replacement resulting in an<br />

incoherent mismatch.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

39

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

The balconies help to reinforce the window<br />

pairing / grouping that underlies the rhythm<br />

of this frontage.<br />

Management or lease arrangements are<br />

helpful to ensure that balconies are not<br />

undermined by clutter.<br />

Glazed balconettes that allow the vertically<br />

proportioned windows to read through.<br />

Window Types<br />

Where window replacement is sought in<br />

existing buildings, they should normally be<br />

done in the original style <strong>and</strong> materials, for<br />

example, timber sliding sash windows on<br />

Georgian, Victorian <strong>and</strong> Edwardian properties,<br />

<strong>and</strong> Crittall windows on inter <strong>and</strong> post-war<br />

buildings. This is most necessary on street<br />

frontages where the windows are visible from<br />

the public realm.<br />

Replacing timber or Crittall windows with<br />

modern alternatives such as UPVC windows,<br />

<strong>and</strong> to a lesser extent, powder coated<br />

aluminium windows are usually unacceptable<br />

not only because they are an unsympathetic<br />

material but also because glazing bar profiles<br />

are usually substantially bigger. The width of<br />

the opening light frame is also usually greater<br />

than the fixed pane. For these reasons they<br />

can look cumbersome. Their extra solidity can<br />

undermine the solid / void relationship of wall<br />

<strong>and</strong> window. Where it involves the<br />

replacement of Crittall windows, the extra<br />

width of the glazing bars can also reduce the<br />

amount of daylight penetration.<br />

However, some powder coated alluminium<br />

products can achieve slenderer profiles <strong>and</strong><br />

can sometimes provide acceptable<br />

replacements on post-war buildings.<br />

Where they are considered acceptable,<br />

window replacements should be applied<br />

universally across the elevation to ensure<br />

consistency.<br />

2.3.2 Balconies<br />

As well as providing useful outside space,<br />

balconies can help articulate a façade. They<br />

tend to work best within larger<br />

developments where they can contribute to<br />

creating a rhythm when they are grouped<br />

vertically across floors <strong>and</strong> horizontally<br />

spaced within regular intervals.<br />

40<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

Conversely, they can be inappropriate if they<br />

are allowed to dominate an elevation by<br />

covering the whole frontage. Continuous<br />

repetition of balconies can appear<br />

monotonous unless they are carefully grouped<br />

in a manner that contributes to the rhythm of<br />

the street frontage. Balconies that continue<br />

horizontally across the entire façade tend to<br />

inappropriately accentuate both the horizontal<br />

proportions <strong>and</strong> the overall scale of the building,<br />

unless they are offset by a strong vertical<br />

proportioning device. They also can also<br />

undermine natural surveillance by obscuring<br />

the views from the windows.<br />

Care must be taken to ensure that balconies<br />

work with the language of the rest of the<br />

façade. A vertically proportioned window can<br />

read as a horizontal one if the bottom half is<br />

obscured by the balcony balustrading. Glazed<br />

or transparent balustrading can address this<br />

<strong>and</strong> ensure natural surveillance is not<br />

impeded. Management or lease arrangements<br />

are nevertheless helpful to ensure that<br />

balconies are kept clear of clutter.<br />

Balconies must be carefully integrated, <strong>and</strong><br />

positively contribute to the order of the<br />

whole of the street frontage. They are also<br />

less likely to fit into a street if the adjacent<br />

frontages have no balconies or similar<br />

features.<br />

Balconies can provide additional sense of<br />

structural depth when they are recessed<br />

within the façade. This must not undermine<br />

the potential natural surveillance benefits;<br />

there should preferably be a window serving a<br />

living room also on the front face of the<br />

building, or the balcony should not be too<br />

deep.<br />

When balconies extend outwards from the<br />

main façade they can appear as “bolt on” after<br />

thoughts. If they project too far from the<br />

façade, they can also appear to unbalance the<br />

building.<br />

These balconies are neatly integrated into<br />

the façade, but care needs to be taken that<br />

natural surveillance is not sacrificed as a result<br />

of recessing the window too deep.<br />

Balconies should avoid looking<br />

as if they are “bolt-on” after thoughts.<br />

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

41

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

Use of different facing materials can have<br />

disastrous results.<br />

Care needs to be taken<br />

to ensure that the new<br />

material is sympathetic<br />

with the local vernacular.<br />

2.3.3 Use of Materials<br />

The use of materials needs to be considered<br />

both in terms of the relationship with the<br />

surrounding built form as well as the<br />

articulation of a façade.<br />

Blending or Contrasting with the Context<br />

Care needs to be taken to ensure that the<br />

new material is sympathetic with the local<br />

vernacular.<br />

The prevailing type of materials in the<br />

immediate surrounds will often influence the<br />

choice of main facing material. It is often<br />

desirable for a new building to blend into its<br />

surrounds by using complementary<br />

materials for the sake of consistency <strong>and</strong> to<br />

ensure that it does not inappropriately draw<br />

the eye or undermine local distinctiveness.<br />

Sometimes the quality <strong>and</strong> nature of the<br />

proposed architecture can dem<strong>and</strong> the use of<br />

contrasting materials. This is particularly the<br />

case if the character of the new building is<br />

underscored by its use of modern materials,<br />

<strong>and</strong> where traditional materials may<br />

undermine the integrity of the proposal.<br />

Where a new building is located next to an<br />

architecturally important building it may be<br />

sometimes necessary to use a material that<br />

allows the existing building to continue to<br />

be read in its own terms – the use of similar<br />

material may blur the boundary or compete<br />

between the existing <strong>and</strong> new building.<br />

The use of red brick draws the eye<br />

towards this building because it<br />

inappropriately contrast with the<br />

yellow stock of the original Victorian<br />

neighbours.<br />

42<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

One-off new buildings often work better with contrasting materials.<br />

The glazed / minimalist approach does not compete with the original buildings <strong>and</strong> allows them to be easily read.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

43

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

This elevation suffers from being too<br />

busy as a result of both the variation in<br />

the use of materials <strong>and</strong> the variety of<br />

recesses <strong>and</strong> projections.<br />

This frontage cleverly reinterprets a<br />

building within the adjacent Victorian<br />

shopping parade using contemporary<br />

materials <strong>and</strong> articulating devices.<br />

The vertical proportions are too exaggerated.<br />

The facade would benefit from some<br />

articulation at the top <strong>and</strong> bottom.<br />

Articulating a Façade<br />

Use of different materials can help to<br />

articulate <strong>and</strong> add interest to a façade. For<br />

instance, as stated above, materials can be<br />

used as a framing device to group elements<br />

such as windows. However, care needs to be<br />

taken not to overload a façade; if too many<br />

materials are used then it can appear untidy or<br />

too busy. To retain the coherence of an<br />

elevation, it is often a good idea to restrict the<br />

number of different materials <strong>and</strong> to employ<br />

the same material in different parts of the<br />

façade.<br />

Attention also needs to be given to ensuring<br />

the right contrast between different materials.<br />

The scale of a frontage can be broken down by<br />

following the rules of classicism of articulating<br />

a base, middle <strong>and</strong> top differently. This can<br />

work well on high frontages. Care needs to be<br />

taken when employing this on lower buildings,<br />

as it might have the opposite effect if it results<br />

in horizontal b<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>and</strong> undermines the<br />

vertical proportions. The scale of a frontage<br />

can be further reduced by articulating the top<br />

floor as a recessive element <strong>and</strong> employing<br />

materials such as glass <strong>and</strong> steel with a<br />

lightweight appearance.<br />

Expressing the various uses of buildings in<br />

different ways can sometimes break down<br />

façades. An open glazed shopfront on the<br />

ground floor normally provides a good<br />

contrast to a solid frontage above.<br />

Materials that work best together often have<br />

a contrasting texture as well as colour; for<br />

example timber, brick, metal <strong>and</strong> render. The<br />

Edwardians were particularly successful in<br />

creating complex patterns from different<br />

colour bricks (as well as stone <strong>and</strong> terracotta).<br />

This is rarely affordable today <strong>and</strong> a reliance<br />

upon different colour brickwork to provide the<br />

necessary articulation is usually insufficient<br />

unless the grain of the bricks provides contrast.<br />

For example, yellow stock bricks <strong>and</strong> smooth<br />

dark grey engineering brick can sometimes<br />

work, particularly if one of the brick types<br />

projects or is recessed against the other.<br />

44<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

The materials have been sensibly<br />

rationalised - the same grey metal finish<br />

has been used to group <strong>and</strong> frame the<br />

windows <strong>and</strong> the roof.<br />

St<strong>and</strong>ing seams can appear crude <strong>and</strong><br />

undermine the quality of a building<br />

particularly if it is characterised by its<br />

minimal reliance on decoration.<br />

The use of different colour bricks<br />

particularly if used in the same plane with<br />

little variation in the grain rarely provides a<br />

successful articulating device.<br />

Poor brick selection can cause problems<br />

with the long term appearance of a<br />

building.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

45

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

Colour needs to be used with care.<br />

Colour that is carefully chosen <strong>and</strong> intelligently<br />

integrated within the façade can sometimes add<br />

interest.<br />

Quality, Ageing <strong>and</strong> Sustainability of<br />

Materials<br />

Good quality materials <strong>and</strong> fixings should<br />

always be used. This is especially the case<br />

with contemporary buildings, which have less<br />

decoration, <strong>and</strong> rely more on the finish of the<br />

materials.<br />

The choice of materials should be influenced<br />

by the way they age, as well as their wider<br />

environmental impact. The Green<br />

Construction Supplementary Planning<br />

Guidance provides detailed advice on the<br />

latter. Materials should normally be<br />

selected that wear well with age <strong>and</strong> last<br />

a long time, <strong>and</strong> those that are known to<br />

weather badly with age should be avoided.<br />

Consideration should be taken given to<br />

weathering properties of materials at the<br />

beginning of the design process. Care needs<br />

to be taken with finishes that require more<br />

maintenance such as some timbers. Other<br />

materials such as some cladding <strong>and</strong> render<br />

finishes can fade <strong>and</strong> appear rather dull after<br />

they have been sun bleached. Examples of<br />

how materials appear after they have been<br />

weathered should normally be sought.<br />

Use of Bright Materials<br />

Care needs to be taken with bright or<br />

colourful materials where they inappropriately<br />

draw attention to particular buildings, <strong>and</strong><br />

away from the street or adjacent spaces. This<br />

is especially the case with large or prominent<br />

buildings which already st<strong>and</strong> out where the<br />

use of neutral colours or, materials that match<br />

their context may be more appropriate. Highly<br />

reflective materials may also be problematic if<br />

they create glare.<br />

Tower block finished in neutral colours<br />

that do not shout out loudly.<br />

46<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

2.3.4 Articulation through Recess<br />

<strong>and</strong> Projection<br />

Facades can be further articulated by<br />

employing recesses <strong>and</strong> projections that can<br />

animate a façade.<br />

Emphasising Vertical Proportions<br />

Vertical proportions can also be reinforced<br />

through contrasting light <strong>and</strong> shade. These<br />

can help accentuate plot widths <strong>and</strong> / or<br />

individual houses through use of repeated<br />

elements such as projecting bay windows <strong>and</strong><br />

recessed front entrances. Where the sub<br />

division of a façade is less apparent, it is<br />

sometimes necessary to employ vertical<br />

shadow lines / niches to break it up. While<br />

downpipes on the front elevation should<br />

normally be avoided, consideration will be<br />

given where they can help to divide up the<br />

elevation into narrow plots, particularly if<br />

they can be neatly integrated within vertical<br />

niches.<br />

When projecting elements are used, care<br />

needs to be taken to ensure that they do not<br />

inappropriately dominate the main façade or<br />

create recesses that undermine the<br />

established building line / sight lines or create<br />

potential hiding places.<br />

Window Reveals<br />

Structural depth can be created by employing<br />

deep window reveals <strong>and</strong> varying the depth<br />

of facing materials. Older buildings are<br />

often characterised by deep reveals as well as<br />

decorative detailing that helps enliven their<br />

façade through contrasts of light <strong>and</strong> shade.<br />

New buildings can often feel flat <strong>and</strong> lifeless in<br />

comparison where insufficient attention has<br />

been given to creating a three dimensional<br />

façade. Unless flush windows are an<br />

intrinsic part of the building’s language,<br />

window reveals will often be sought which<br />

provide the façade with some depth.<br />

Recess <strong>and</strong> projection of the entire façade<br />

can undermine the legibility of the street<br />

or threshold space <strong>and</strong> be at odds with the<br />

building line.<br />

This frontage may be relatively well<br />

organised, but the lack of window<br />

reveals result in a flat, lifeless façade.<br />

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

47

2.3 ELEVATIONAL TREATMENT<br />

Deep window reveals provide facades with a sense of structural depth (top <strong>and</strong> below right). The<br />

flush vertically articulated planar glass is an intrinsic element of the bottom left image. The I-beams<br />

along the floor plates <strong>and</strong> the deeply recessed ground floor provides contrast <strong>and</strong> depth.<br />

48<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

2.4 UNIFORM / CONSISTENT<br />

STREET FRONTAGES<br />

2.4.1 Reinforcing Rhythm <strong>and</strong><br />

Uniformity<br />

Many of <strong>Islington</strong>’s street frontages are<br />

characterised by Georgian, Victorian <strong>and</strong><br />

Edwardian terraces or parades. Less common<br />

are streets with inter / post-war housing <strong>and</strong><br />

/ or semi-detached / detached houses. The<br />

majority of pre-1914 residential street<br />

frontages typically employ a consistent<br />

rhythm resulting from a consistent roofline<br />

<strong>and</strong> the repetition of the formal ordering<br />

of each individual house facade. This order<br />

is created by the proportioning system <strong>and</strong><br />

grouping of the fenestration, as well as<br />

decorative detailing such as the cornicing.<br />

Where these features have been lost, the<br />

rhythm <strong>and</strong> unity of the terrace / parade /<br />

row of villas is often disrupted which normally<br />

undermines the overall quality of the<br />

streetscape. For this reason, change to the<br />

consistent pattern will normally be resisted.<br />

Where features have already been lost, their<br />

restoration will be sought whenever possible.<br />

Whilst they rarely have any of the decorative<br />

interest <strong>and</strong> geometric proportions of pre-<br />

1939 frontages, many post-war frontages<br />

also employ a repeated elements that can be<br />

easily disrupted by alterations <strong>and</strong> extensions<br />

that undermine the overall rhythm.<br />

2.4.2 Protecting Unaltered<br />

Rooflines<br />

The Front Roofline<br />

An important constituent to the rhythm <strong>and</strong><br />

uniformity of a residential terrace or street is<br />

the roofline. A typical terrace or row of<br />

detached / semi-detached houses is designed<br />

with a consistent height at the front <strong>and</strong> rear.<br />

A well defined roofline throughout helps give<br />

terraces their inherent unity. It also allows the<br />

repeated articulation to provide the natural<br />

A typical Victorian terrace employing a consistent<br />

rhythm resulting from the repetition of the formal<br />

ordering of each individual house façade.<br />

A Georgian terrace with a consistent rhythm.<br />

The rhythm <strong>and</strong> unity of post-war housing can<br />

also be undermined by insensitive changes.<br />

2.4 UNIFORM / CONSISTENT STREET FRONTAGES<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

49

2.4 UNIFORM 2.5 / CONSISTENT Residential STREET Rear Extensions<br />

FRONTAGES<br />

A terrace with existing roof extensions may have the<br />

opportunity of its unity being reconciled through<br />

allowing additional roof extensions to fill the gaps.<br />

A single roof extension undermines the<br />

unity of an otherwise uniform terrace.<br />

Further extensions could nevertheless be<br />

even more ruinous <strong>and</strong> potentially create<br />

a “gap tooth” appearance.<br />

Butterfly or valley roofs are particularly<br />

important features, which reinforce a sense of<br />

rhythm normally at the rear.<br />

rhythm that underpins the frontages. An<br />

extension that projects above or alters the<br />

original roofline at the front or rear can often<br />

disrupt this rhythm / unity <strong>and</strong> introduce<br />

features that fail to respect the scale, form,<br />

<strong>and</strong> character of the street frontage. Typically<br />

a roof extension also involves raising the flank<br />

boundary parapets <strong>and</strong> chimneys that further<br />

draws attention to itself. These considerations<br />

will be especially pertinent when the<br />

roofline is unaltered or minimally altered. In<br />

these cases there will be a strong<br />

presumption against any alteration or<br />

extension beyond the existing roofline.<br />

When considering the scope for change it is<br />

necessary to consider the particular<br />

terrace / uniform street frontage in<br />

question. It is not uncommon for there to be<br />

more than one type of frontage on one side<br />

of one street. What might be acceptable in<br />

one part of the street will not necessarily<br />

apply to the next terrace even if it is<br />

physically connected <strong>and</strong> on the same side of<br />

the same street. The same is true with<br />

terraces on the opposite side of the street.<br />

Outside conservation areas, there is<br />

sometimes scope for skylights providing they<br />

follow the profile of the existing roofline <strong>and</strong><br />

conform to the st<strong>and</strong>ards set out below.<br />

The Rear Roofline<br />

While it is normally less visible from the public<br />

realm, the same principles apply to the<br />

roofline at the rear as well as the front,<br />

particularly where they are visible through<br />

gaps in the street frontage or where the<br />

roofline has a strong rhythm (such as<br />

repeated butterfly windows). Even when this<br />

is not the case, a break in a largely unaltered<br />

roofline is likely to have an adverse impact<br />

upon the quality of the private realm.<br />

Nevertheless, there will sometimes be scope<br />

for a small dormer window on pitched roofs<br />

at the rear providing it is no wider than the<br />

existing upper floor windows <strong>and</strong> conforms to<br />

the st<strong>and</strong>ards set out below.<br />

50<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

2.4.3 Rooflines with Existing<br />

Alterations / Extensions<br />

Where the original roofline has been broken,<br />

the extent <strong>and</strong> nature of the existing roof<br />

additions will determine the scope for further<br />

change. For instance, a single roof<br />

extension that pre-dates the adopted UDP<br />

on an otherwise unbroken roofline will not<br />

normally constitute a precedent for further<br />

roof additions. While there are no absolute<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ards in these circumstances, the scope<br />

for roof extensions will normally be<br />

dependent on the following criteria:<br />

• The number of existing roof extensions,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the extent to which the unity /<br />

consistency of the roofline has already<br />

been compromised.<br />

• The length of the terrace – a short<br />

terrace with existing roof extensions may<br />

have the opportunity of its unity being<br />

reconciled through allowing additional roof<br />

extensions to fill the gaps. On a long terrace<br />

with houses in separate ownership,<br />

this is less likely to occur.<br />

• The age of the extensions – an extension<br />

allowed before the current UDP st<strong>and</strong>ards<br />

<strong>and</strong> policies will not normally set a<br />

precedent for new extensions.<br />

• Listed buildings <strong>and</strong> terraces within<br />

conservation areas will also be<br />

respectively subject to the detailed<br />

individual consideration of the listed<br />

building issues <strong>and</strong> Conservation Area<br />

<strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong>lines.<br />

On semi-detached villas, one sided<br />

extensions will normally be resisted where<br />

they undermine the symmetry of the<br />

original building. Two sided extensions on<br />

semi-detached villas <strong>and</strong> extensions above<br />

detached villas will usually only be considered<br />

where they exist elsewhere in the street on<br />

identically designed buildings.<br />

This roof extension has been generously set<br />

back but is still visible from longer views.<br />

One sided extensions on semi detached<br />

buildings undermine the symmetry of the<br />

original building. Despite being on both<br />

sides of the building, roof railings are alien<br />

to Victorian residential frontages <strong>and</strong> will<br />

normally be resisted.<br />

2.4 UNIFORM / CONSISTENT STREET FRONTAGES<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

51

2.4 UNIFORM 2.5 / CONSISTENT Residential STREET Rear Extensions<br />

FRONTAGES<br />

A terrace with pitched ridged roofs with well<br />

integrated <strong>and</strong> uniformally designed dormer<br />

windows that maintain the rhythm of the terrace.<br />

A traditional mansard roof with dormer windows.<br />

Main Types of Roof Extensions<br />

Where they are acceptable, roof<br />

extensions on residential terraces or,<br />

villas must be restricted to a single storey.<br />

The profile <strong>and</strong> configuration of the existing<br />

extensions should normally be followed<br />

except in those cases where the existing<br />

design is considered out of character. The<br />

following are the most common types of roof<br />

extension:<br />

• A mansard roof is a traditional type of roof<br />

that is generally not appropriate for<br />

contemporary buildings. There are two<br />

main types. (a) Flat mansard<br />

incorporating steep front <strong>and</strong> back <strong>and</strong><br />

almost flat top. These are usually not<br />

acceptable in conservation areas.<br />

(b) Traditional mansard incorporating a<br />

steep angled front <strong>and</strong> rear <strong>and</strong> shallow<br />

angled roof up to the ridge-line. Dormer<br />

windows are best suited to both types.<br />

• Pitched ridge roofs are occasionally used<br />

for roof extensions instead of a mansard.<br />

They can accommodate dormer windows<br />

or skylights that follow the roof profile if<br />

outside a conservation area (refer to page<br />

54).<br />

• Contemporary roof extensions typically<br />

incorporate modern materials (with a<br />

lightweight appearance such as glass <strong>and</strong><br />

steel) <strong>and</strong> incorporate a vertical frontage<br />

<strong>and</strong> flat roof that is usually well set back<br />

behind the front parapet upst<strong>and</strong>. They<br />

are most appropriate on post-war or<br />

contemporary styled buildings. Sometimes<br />

there is scope for contemporary<br />

extensions on Victorian terraces where<br />

existing contemporary extensions already<br />

exist in the terrace or on corner buildings<br />

which are different / st<strong>and</strong> out from the<br />

remainder of the terrace.<br />

A glass <strong>and</strong> steel contemporary roof extension<br />

incorporating an oversailing brise soleil.<br />

52<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

72˚<br />

A flat mansard roof<br />

2.4 UNIFORM / CONSISTENT STREET FRONTAGES<br />

25˚<br />

72˚<br />

A traditional double pitch mansard roof<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

53

2.4 UNIFORM 2.5 / CONSISTENT Residential STREET Rear Extensions<br />

FRONTAGES<br />

This dormer window is inappropriately<br />

elaborate. It is too solid <strong>and</strong> large.<br />

Types of Roof Level Fenestration<br />

• Dormer windows are typically<br />

incorporated within pitched roofs <strong>and</strong><br />

mansard roofs. They generally should<br />

be designed so they do not draw the<br />

eye. Dormer windows usually work best<br />

where they are no wider overall than the<br />

windows in the façade, especially where<br />

they line up with the windows below.<br />

Larger dormers are sometimes acceptable<br />

where a precedent has already been<br />

set elsewhere in the terrace. The solid<br />

surrounds (cheeks) should be kept as<br />

unobtrusive <strong>and</strong> slender as possible – a<br />

simple lead cloaking with a double hung<br />

sash timber window is often the best<br />

solution. Except for the window frame<br />

<strong>and</strong> cloaking material, there should never<br />

be any solid face. The dormer should be<br />

positioned a clear distance below the<br />

ridge-line, <strong>and</strong> clear <strong>and</strong> proud of the<br />

boundary parapets, <strong>and</strong> above the line of<br />

the eaves.<br />

• Skylights that follow the roof profile can<br />

be appropriate where it is important to<br />

retain the profile of the roof slope. They<br />

are normally undesirable on mansard roofs<br />

or in conservation areas, where skylights<br />

appear as an intrusive / alien feature. They<br />

should also not crowd the roof – they<br />

should be limited to one or two per roof<br />

slope that are no wider than the window<br />

apertures in the main façade. The<br />

skylights should be designed with a<br />

slender profile so they do not appear to<br />

rise more than the typical depth of a<br />

window above the roof slope.<br />

This dormer window is unacceptable because:<br />

(1) it extends full width <strong>and</strong> loses the angle of<br />

the pitch roof; (2) it incorporates a solid face;<br />

(3) the vertical hung tiles are an inappropriate<br />

material; (4) it disrupts an otherwise unaltered<br />

roofline within the terrace; (5) the vertical<br />

brick built parapet boundary walls draw further<br />

attention to itself.<br />

54<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006

2.4.4 Side Extensions on the<br />

Street Frontage<br />

Along residential streets, which are<br />

organised as a series of semi-detached villas<br />

or houses, there is sometimes development<br />

pressure for front side extensions in the gaps<br />

between the houses. Normally infilling<br />

these gaps with a side extension is likely to<br />

undermine the rhythm of the street <strong>and</strong> / or<br />

the symmetry of the mirror image houses<br />

within the semi-detached formation. There<br />

may be scope for extensions where the<br />

proposal restores the symmetry <strong>and</strong> does not<br />

undermine the overall rhythm of the street<br />

frontage, or dominate the existing building(s).<br />

Side extensions often unbalance the<br />

original symmetry.<br />

2.4 UNIFORM / CONSISTENT STREET FRONTAGES<br />

Skylights should not crowd a roof slope.<br />

<strong>Islington</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> December 2006<br />

55

2.4 UNIFORM 2.5 / CONSISTENT Residential STREET Rear Extensions<br />

FRONTAGES<br />

The front boundary railings are so high they<br />

feel like security railings <strong>and</strong> undermine the<br />

relationship of the frontage with the street.<br />

2.4.5 Front Boundaries<br />

Front boundary walls are typically part of the<br />

uniform design of the residential frontage.<br />

They often incorporate dwarf walls <strong>and</strong> / or<br />

low-level railings. There will always be a<br />

presumption in favour of this arrangement. As<br />