REGINE Regularisations in Europe Final Report - European ...

REGINE Regularisations in Europe Final Report - European ...

REGINE Regularisations in Europe Final Report - European ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

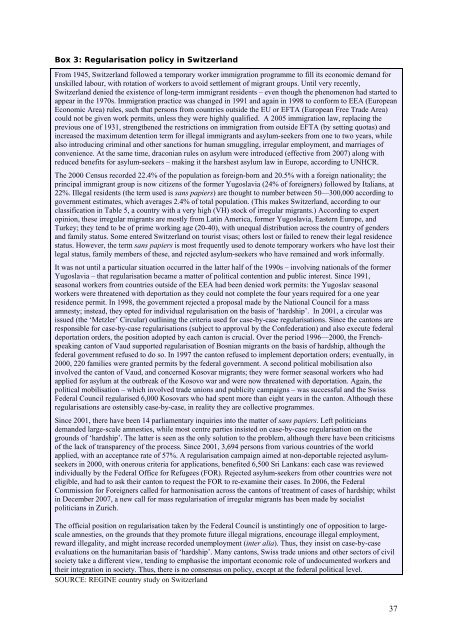

Box 3: Regularisation policy <strong>in</strong> Switzerland<br />

From 1945, Switzerland followed a temporary worker immigration programme to fill its economic demand for<br />

unskilled labour, with rotation of workers to avoid settlement of migrant groups. Until very recently,<br />

Switzerland denied the existence of long-term immigrant residents – even though the phenomenon had started to<br />

appear <strong>in</strong> the 1970s. Immigration practice was changed <strong>in</strong> 1991 and aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> 1998 to conform to EEA (<strong>Europe</strong>an<br />

Economic Area) rules, such that persons from countries outside the EU or EFTA (<strong>Europe</strong>an Free Trade Area)<br />

could not be given work permits, unless they were highly qualified. A 2005 immigration law, replac<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

previous one of 1931, strengthened the restrictions on immigration from outside EFTA (by sett<strong>in</strong>g quotas) and<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased the maximum detention term for illegal immigrants and asylum-seekers from one to two years, while<br />

also <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g crim<strong>in</strong>al and other sanctions for human smuggl<strong>in</strong>g, irregular employment, and marriages of<br />

convenience. At the same time, draconian rules on asylum were <strong>in</strong>troduced (effective from 2007) along with<br />

reduced benefits for asylum-seekers – mak<strong>in</strong>g it the harshest asylum law <strong>in</strong> <strong>Europe</strong>, accord<strong>in</strong>g to UNHCR.<br />

The 2000 Census recorded 22.4% of the population as foreign-born and 20.5% with a foreign nationality; the<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>cipal immigrant group is now citizens of the former Yugoslavia (24% of foreigners) followed by Italians, at<br />

22%. Illegal residents (the term used is sans papiers) are thought to number between 50—300,000 accord<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

government estimates, which averages 2.4% of total population. (This makes Switzerland, accord<strong>in</strong>g to our<br />

classification <strong>in</strong> Table 5, a country with a very high (VH) stock of irregular migrants.) Accord<strong>in</strong>g to expert<br />

op<strong>in</strong>ion, these irregular migrants are mostly from Lat<strong>in</strong> America, former Yugoslavia, Eastern <strong>Europe</strong>, and<br />

Turkey; they tend to be of prime work<strong>in</strong>g age (20-40), with unequal distribution across the country of genders<br />

and family status. Some entered Switzerland on tourist visas; others lost or failed to renew their legal residence<br />

status. However, the term sans papiers is most frequently used to denote temporary workers who have lost their<br />

legal status, family members of these, and rejected asylum-seekers who have rema<strong>in</strong>ed and work <strong>in</strong>formally.<br />

It was not until a particular situation occurred <strong>in</strong> the latter half of the 1990s – <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g nationals of the former<br />

Yugoslavia – that regularisation became a matter of political contention and public <strong>in</strong>terest. S<strong>in</strong>ce 1991,<br />

seasonal workers from countries outside of the EEA had been denied work permits: the Yugoslav seasonal<br />

workers were threatened with deportation as they could not complete the four years required for a one year<br />

residence permit. In 1998, the government rejected a proposal made by the National Council for a mass<br />

amnesty; <strong>in</strong>stead, they opted for <strong>in</strong>dividual regularisation on the basis of ‘hardship’. In 2001, a circular was<br />

issued (the ‘Metzler’ Circular) outl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the criteria used for case-by-case regularisations. S<strong>in</strong>ce the cantons are<br />

responsible for case-by-case regularisations (subject to approval by the Confederation) and also execute federal<br />

deportation orders, the position adopted by each canton is crucial. Over the period 1996—2000, the Frenchspeak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

canton of Vaud supported regularisation of Bosnian migrants on the basis of hardship, although the<br />

federal government refused to do so. In 1997 the canton refused to implement deportation orders; eventually, <strong>in</strong><br />

2000, 220 families were granted permits by the federal government. A second political mobilisation also<br />

<strong>in</strong>volved the canton of Vaud, and concerned Kosovar migrants; they were former seasonal workers who had<br />

applied for asylum at the outbreak of the Kosovo war and were now threatened with deportation. Aga<strong>in</strong>, the<br />

political mobilisation – which <strong>in</strong>volved trade unions and publicity campaigns – was successful and the Swiss<br />

Federal Council regularised 6,000 Kosovars who had spent more than eight years <strong>in</strong> the canton. Although these<br />

regularisations are ostensibly case-by-case, <strong>in</strong> reality they are collective programmes.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce 2001, there have been 14 parliamentary <strong>in</strong>quiries <strong>in</strong>to the matter of sans papiers. Left politicians<br />

demanded large-scale amnesties, while most centre parties <strong>in</strong>sisted on case-by-case regularisation on the<br />

grounds of ‘hardship’. The latter is seen as the only solution to the problem, although there have been criticisms<br />

of the lack of transparency of the process. S<strong>in</strong>ce 2001, 3,694 persons from various countries of the world<br />

applied, with an acceptance rate of 57%. A regularisation campaign aimed at non-deportable rejected asylumseekers<br />

<strong>in</strong> 2000, with onerous criteria for applications, benefited 6,500 Sri Lankans: each case was reviewed<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividually by the Federal Office for Refugees (FOR). Rejected asylum-seekers from other countries were not<br />

eligible, and had to ask their canton to request the FOR to re-exam<strong>in</strong>e their cases. In 2006, the Federal<br />

Commission for Foreigners called for harmonisation across the cantons of treatment of cases of hardship; whilst<br />

<strong>in</strong> December 2007, a new call for mass regularisation of irregular migrants has been made by socialist<br />

politicians <strong>in</strong> Zurich.<br />

The official position on regularisation taken by the Federal Council is unst<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gly one of opposition to largescale<br />

amnesties, on the grounds that they promote future illegal migrations, encourage illegal employment,<br />

reward illegality, and might <strong>in</strong>crease recorded unemployment (<strong>in</strong>ter alia). Thus, they <strong>in</strong>sist on case-by-case<br />

evaluations on the humanitarian basis of ‘hardship’. Many cantons, Swiss trade unions and other sectors of civil<br />

society take a different view, tend<strong>in</strong>g to emphasise the important economic role of undocumented workers and<br />

their <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>in</strong> society. Thus, there is no consensus on policy, except at the federal political level.<br />

SOURCE: <strong>REGINE</strong> country study on Switzerland<br />

37