EXPLAINING SOCIAL EXCLUSION - Institut für Soziologie

EXPLAINING SOCIAL EXCLUSION - Institut für Soziologie

EXPLAINING SOCIAL EXCLUSION - Institut für Soziologie

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Other Journals from Barmarick Publications<br />

Equal Opportunities International<br />

Managerial Law<br />

Management Research News<br />

Managerial Finance<br />

International Journal of Wine Marketing<br />

Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics<br />

Cross Cultural Management<br />

Humanomics<br />

Review of Accounting and Finance<br />

<strong>EXPLAINING</strong><br />

<strong>SOCIAL</strong> <strong>EXCLUSION</strong><br />

Edited by Jenny Jarman<br />

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy Vol. 21 No. 4/5/6 2001<br />

Copyright © 2001 Barmarick Publications.<br />

Authors reserve all rights.<br />

Enhoimes Hall, Patrington, Hüll, East Riding of Yorkshire,<br />

England, HUI2 OPR.<br />

ISSN 0144-333X

Editor:<br />

Review Editor:<br />

Associate Editorst<br />

Barric O. Pettman,<br />

International <strong>Institut</strong>e of Social Economics<br />

Jill Manthorpe,<br />

University of Hüll,<br />

Department of Social Work,<br />

Hüll HU6 7RX<br />

Erik Allardt, University of Helsinki<br />

Simon Bekkcr, The Urban Foundation, Johannesburg<br />

Berch Berberoglu, University of Navada<br />

Robert Bierstedt, University of Virginia<br />

Tom Bottomore, University of Sussex<br />

Sally Bould, University of delaware<br />

Benjamin P. Bowser, California Säte University, Hayward<br />

Otar Brox, University of Tromso<br />

Jose Cazaria, University of Granada<br />

Mohamed Cherkaoui, University of Paris - Sorbonne<br />

John Cross.Vassar College<br />

Y. D. Dam'ie, University of Poona<br />

K. Dobbelaere, Catholic University of Leuven<br />

Tim Dowd, Emory University<br />

John Eldridge, University of Glasgow<br />

Maria-Pilar Garcia, Universidad Simon Bolivar<br />

Anthony Giddens, University of Cambridge<br />

Gergory Gizelis, Academy of Athens<br />

Björn Gustaven, Oslo Work Research <strong>Institut</strong>es<br />

Leonard M. Henny, State University of Utrech<br />

H. J. Hoffman-Nowotny, University of Zürich<br />

Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao, <strong>Institut</strong>e of Ethonology, Taiwan<br />

Ronald N. Jacobs, University at Albany<br />

Mette Jensen, Roskilde Universitetcenter<br />

Ken Judge, University of Kent, Canterbury<br />

David Karen, Bryn Mawr College<br />

Lisa A. Keister, The Ohio State University<br />

Hiroshi Komai, University of Tsukaba<br />

Cheng-shu Kao, Tunghal University, Taiwan<br />

Kilma'n Kulsclr, Hungarian Academy of Sciences<br />

Jolanta Kulspinka, University of Lodz<br />

David Macarov, University of Jerusalem<br />

Donald Mac-Rae, London School of Economics<br />

Zdravko Minar, University of Ljubljana<br />

Alfonso Morales, University of Texas at El Paso<br />

Guiseppe Morosini, Universita delgi stud di Torino<br />

Anna Olszewska, Instyut Filozofii i Socjologii, Warsaw<br />

Eise 0yen, University of Bergen<br />

David N. Pellow, Universiry of Colorado at Boulder<br />

Glanfranco Poggi, Iniversity of Edinburgh<br />

A. G. Schutte, University of Wirwatersrand<br />

Duncan Timms, University of Stirling<br />

Renato Treves, University of Milan<br />

Joji Watanuki, Sophia University<br />

Peter Weingart, University of Bielefeid<br />

Wlodzimierz Wesolowski. Polish Academy<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001<br />

Contents<br />

Explaining Social Exclusion<br />

by Jenny Jarman<br />

Page<br />

Social exclusion and public policy: the relationship between<br />

local school admission arrangements and segregation<br />

by poverty"<br />

by Stephen Gorard, Chris Taylor and John Fitz 10<br />

Young People's Explanations and Experiences of Social<br />

Exclusion: Retrieving Bourdieu's Concept of Social Capital<br />

by Virginia Morrow 37<br />

A Story of "Difference", A Different Story: Young Homeless<br />

Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual People<br />

by Shirley Prendergast, Gillian A. Dünne, David Telford 64<br />

Unemployment and Social Mobility in East German<br />

by Reinhold Sackmann, Michael Windzio and<br />

Matthias Wingens 92<br />

Unemployment without Social Exclusion: Evidence from<br />

Young People In Eastern Europe<br />

by Ken Roberts \<br />

New Fatherhood in Practice? Parental Leave in the UK<br />

by Esther Dermott 145<br />

An International Comparative Analysis of Marriage<br />

Patterns and Social Stratification<br />

by Ken Prandy and Frank L. Jones 165<br />

Inclusion or Exclusion? Reflections on the Evidence of<br />

declining racial disadvantage in the British labour market<br />

by Paul Iganski, GeoffPayne and Judy Roberts \4<br />

Risk of Social Exclusion in Later Life: How well do the<br />

pension Systems of Britain and the US accommodate<br />

women's paid and unpaid work<br />

by Jay Ginn 212<br />

3<br />

j

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 92<br />

Unemployment and social mobility in East Germany<br />

by Reinhold Sackmann, Professor, EMPAS, University of Bremen,<br />

Michael Windzio, PD, EMPAS, University of Bremen and Matthias<br />

Wingens, PD, University of Bremen<br />

High unemployment rates are still a major problem faced by many<br />

European societies; the Situation is especially grave during the transition<br />

process from a communist to a market economy. We know that unemployment<br />

has effects on the psychological well-being of persons<br />

affected (Kieselbach 2000) and on the functioning of communities hit<br />

by a high concentration of unemployment (Jahoda, Lazarsfeld and<br />

Zeisel 1971). However, our knowledge with regard to the long-term effects<br />

of unemployment on careers is rather limited. Some authors conclude<br />

that unemployment is only a transition phase in the life course<br />

and has a limited effect on long-term careers (Mutz et al. 1995). In contrast,<br />

other authors argue that unemployment is a first step towards<br />

processes of social exclusion, featuring unemployment äs a major<br />

mechanism of disintegrating certain groups from Society (Kronauer,<br />

Vogel and Gerlach 1993). Major social policy interventions fostering<br />

workfare instead of welfare äs well äs programs focussing on employability<br />

build on this kind of social diagnosis.<br />

The effects of youth unemployment on careers may be even<br />

more crucial. Youth unemployment in transition societies is seen äs a<br />

critical life event, because long-term effects of unemployment may not<br />

only leave a "scar" on the careers of the individuals (OECD 1998) but<br />

can also be a cause of major social problems in transition societies, e.g.<br />

criminal behaviour and, or racist behaviour, destabilising the fragile<br />

equilibrium of accelerated social change in transition societies.<br />

Thus, there is a need for empirical research on the long-term effects<br />

of unemployment. Methodologically, longitudinal analysis, especially<br />

event history analysis, was a major improvement for the study of<br />

the connection of life courses and social change. The aim of this article<br />

is to look into the long-term effects of unemployment on social mobility,<br />

using longitudinal data on young East Germans during the transition<br />

period. In order to simultaneously pursue transitions and<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 93<br />

trajectories, two methods are used: event-history and optimalmatching<br />

analysis.<br />

Data set<br />

For the empirical analysis of the East German Career Study, a longitudinal<br />

data set of young East German labour market entry cohorts is<br />

used, which was set up at the Special Collaborative Centre 186. The<br />

data set (Weymann, Sackmann and Wingens 1999) consists of 3776<br />

young skilled workers who participated in an apprenticeship and<br />

young university graduates, all taking exams in 1985 (before the transformation),<br />

in 1990 (the reunification year) and 1995. The data set is<br />

not representative for all young people in East Germany, but only for<br />

the two most numerous qualification levels: young skilled workers and<br />

Professionals. Thus we restrict generalisations of our results to these<br />

groups. For questions of exclusion, you have to take into account that<br />

the "unqualified" are not part of the sample. However, the "unqualified"<br />

make up a very small group in East Germany, äs they only account<br />

for 3% of the cohort of young people.<br />

Theoretically, we take a dynamic approach to the phenomenon<br />

of exclusion. Cross-sectional data on unemployment can be misleading,<br />

äs they suggest that uniform levels of unemployment refer to a<br />

constant group of the unemployed. Longitudinal studies that use life<br />

event analysis have improved the dynamic analysis of unemployment.<br />

Studies usually focus on processes that cause the selectivity of becoming<br />

unemployed and processes causing exit from unemployment. Research<br />

results from this method suggest that unemployment is a<br />

transient position (Mutz et al. 1995). While results gained with this<br />

method fürthered unemployment research, it also has some blind<br />

spots. If one only looks at single transitions of unemployment, one can<br />

miss its long-term effects. The starting point of our analysis is to look<br />

into the long-term effects of unemployment for careers. To get an answer<br />

to this question, we use two methods: a) we use event-history<br />

analysis to see how unemployment (äs a time-dependent variable) influences<br />

processes of social mobility; b) we use the relatively new<br />

method of optimal matching analysis to find patterns of careers.

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 94<br />

Since the 1980s, the new method called optimal matching analysis<br />

enables fmding patterns of sequences of states (Abbott 1995).<br />

Originally this method was used in DNA-analysis in genetics, but recently<br />

there is a growing literature of applications in life-course research<br />

(Abbott and Hrycack 1990; Han and Moen 1999; Halpin and<br />

Chan 1998; Scherer 1998). The optimal matching analysis uses algorithms<br />

that compute the similarity of sequences of states. In a second<br />

step the results of the similarity values are usually grouped by cluster<br />

analysis. The aim of this method is to find types of careers using the information<br />

of whole careers.<br />

Long-term effects of Unemployment spells on social mobility:<br />

Some hypotheses<br />

Research on the long-term effects of Unemployment spells on social<br />

mobility has not been conclusive. There is a set of competing theories<br />

resulting in contradictory hypotheses, which - to a certain extent - can<br />

be tested in empirical research. If one wants to model the effect of unemployment<br />

on mobility in the context of a transformation of a society,<br />

one has to specify what could be meant by the effects of unemployment<br />

on the one band and by the effects of structural transformation on<br />

the other.<br />

For the effects of Unemployment, existing labour market theories<br />

suggest four types of possible effects for the individual. One concerns<br />

the direction of social mobility influenced by a single spell of<br />

Unemployment. Theories of exclusion conclude a spiralling unemployment<br />

effect; unemployment is seen äs a decisive element for<br />

downward mobility (c.f. Kronauer et al. 1993). This view contrasts<br />

with theories of the transitory nature of unemployment, which conclude<br />

that unemployment simply indicates a switch in one's career,<br />

whatever direction this mobility process may take (c.f. Mutz et al.<br />

1995). Hypothesis one is: unemployment only influencesprocesses of<br />

downward social mobility.<br />

The second hypothesis refers to cumulative processes of unemployment.<br />

Exclusion theories argue that unemployment spells are not<br />

evenly distributed among cases. Unemployment may be characterised<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 95<br />

äs a cumulative process. Some people become unemployed repeatedly.<br />

Signalling theory (Spence 1973) suggests similar effects: the longer<br />

the overall length of unemployment in a person's career, the less likely<br />

that an employer entrusts a rise in position to this person (Inkmann,<br />

Klotz and Pohlmeier 1998). Hypothesis two is: the higher the cumulative<br />

duration of all unemployment spells, the less likely upward social<br />

mobility.<br />

The third hypothesis refers to human capital and coping mechanisms<br />

for unemployment. Human capital theory suggests that the<br />

longer a single unemployment spell, the more likely a loss of human<br />

capital thereafter (Mincer and Ofek 1993). One would conclude that<br />

long spells of unemployment lead to downward social mobility. Contrary<br />

to this is the Suggestion of coping theory: People become more<br />

risk-averse after a spell of long-term unemployment. Therefore, mobility<br />

is reduced after long unemployment spells. In the USA, young<br />

people affected by a deprivation of their parental home caused by unemployment<br />

during the 1930s, were more risk-averse during their<br />

work-history than people who did not have this experience during their<br />

youth (Eider 1974). Similar coping-effects might be the resultof an experience<br />

of unemployment during adulthood. Hypothesis three is: the<br />

longer an unemployment spell, the less likely is it that there will be social<br />

mobility afterwards.<br />

The fourth hypothesis refers to processes of downwardspiralling<br />

mobility. Downward-spiralling suggests that downward mobility<br />

to qualification-inadequate positions is irreversible. Contrary to<br />

this, one might suppose that positions below one's level of qualification<br />

produce a kind of personal tension äs people feel they have more<br />

Potential than their current position suggests. Therefore, they try to rebalance<br />

individual resources and positions by moves of individual<br />

counter-mobility (Tuma 1985; Becker and Zimmermann 1995). Hypothesis<br />

four is that people in a position below their level ofqualification<br />

will be more likely to make transitions of upward mobility.<br />

Sociologically inspired labour market theory underlined the importance<br />

of structural components for the explanation of processes of

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 96<br />

mobility in individual careers (Kalleberg and S0rensen 1979). Processes<br />

of individual careers are embedded in a structural process of social<br />

change. An understanding of the macro-social transformation is<br />

important for the explanation of individual mobility. This especially<br />

holds true in the case of accelerated social change e.g. in countries of<br />

transition from a communist economy to a market economy. One advantage<br />

of event-history analysis is that it allows a dynamic analysis of<br />

macro-social processes and individual processes, thus differentiating<br />

micro- and macro-level causation (Biossfeld and Rohwer 1995).<br />

Three possible effects of the structural components of the transition<br />

process on individual mobility are important. A first thesis is on<br />

the general direction of structural change of mobility due to the transition<br />

process. Some theoreticians of the transition suggested a general<br />

trend of downward mobility in East Germany. Like the Mezzogiorno<br />

in Italy, peripheral East Germany loses its own economic potential;<br />

general downward mobility therefore prevails. Contrary to this, modernisation<br />

theory suggests a modernisation vis a vis the backwardness<br />

of the communist economic structure. Especially the modemising<br />

trend towards more employment in the tertiary sector is supposed to be<br />

accompanied by more upward mobility (Zapf 1994; Biossfeld 1989).<br />

Hypothesis five is: a general rise of employment in the tertiary sector<br />

causes more individual upward mobility.<br />

A further thesis refers to the effect of the general level of unemployment<br />

on mobility. One could argue that during periods of recession<br />

the number of involuntary exits rises, forcing people to leave Jobs.<br />

Thus higher unemployment levels would lead to higher mobility levels.<br />

Contrary to this, one Suggestion is that a rise of the general level of<br />

unemployment causes a higher risk in mobility moves (Schettkat<br />

1992; DiPrete and Nonnemaker 1997). Therefore, the overall level of<br />

mobility is lower in times of high unemployment than in times of labour<br />

shortage, when there is more incentive and less risk to move between<br />

Jobs. Hypothesis six is: a general rise of unemployment reduces<br />

individual mobility.<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 97<br />

A last thesis refers to the connection between structural and organisational<br />

change. As evolutionary Organisation theory suggests<br />

(Hannan and Carroll 1992), social mobility is more likely after new<br />

companies have been formed and old companies have been closed than<br />

after the enlargement and shrinkage of established companies. Haveman<br />

and Cohen (1994) showed that in the banking sector of California<br />

a growing number of Company formations, mergers and closures<br />

caused a higher rate of social mobility of employees. Especially the<br />

quick privatisation policy (Pickel and Wiesenthal 1997) of the East<br />

German transformation (with high rates of firm formations and firm<br />

closures) could have caused more social mobility during this period.<br />

Hypothesis seven is: a general rise offormation of companies raises<br />

the likelihood of upward mobility, whereas a general rise ofclosure of<br />

companies raises the likelihood of downward mobility.<br />

The following event-history analysis focusses on these seven<br />

hypotheses. To reduce the risk of a maladjusted model, we controlled<br />

for a number of variables: labour force experience; occupational prestige<br />

of current Job; gender; children; employment in the public sector;<br />

entry-cohort; number of preceding employment history spells; and rriigration<br />

to West Germany. We will not comment on the results of these<br />

control-variables, which were discussed in other publications (Weymann,<br />

Sackmann and Wingens 1999).<br />

Results of the event history analysis<br />

The aim of our event-history analysis is to find out what the effect of<br />

unemployment on social mobility career transitions is. Young East<br />

Germans, who took their exams in 1985 and 1990, were observed until<br />

the middle of 1997. As unemployment did not exist in GDR the period<br />

"at risk" started in November 1989. As we did know the length of the<br />

employment spells before 1989, this information was used in the<br />

model thus avoiding "left censoring" (Guo 1993). A highly flexible<br />

piecewise constant exponential model with competing risks was used.<br />

The central idea of such a piecewise constant model is to split the process<br />

time axis into intervals and to allow a Variation of the constant between<br />

the intervals. The model allows to control approximately for the

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 98<br />

time dependence of the process without a previous decision about the<br />

shape of the function. Time intervals of twelve months were used. An<br />

upward mobility transition was defmed äs a transition between two<br />

Jobs whereby the second Job has an at least 5% higher level of occupational<br />

prestige on the Treiman-Ganzeboom prestige index from 1996.<br />

Downward mobility is defmed likewise with the second Job having an<br />

at least 5% lower level of prestige on the Treiman-Ganzeboom index.<br />

Lateral mobility transitions are defmed äs all other Job changes.<br />

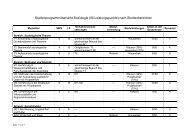

Table l (overleaf) shows the results of the event history analysis.<br />

Numbers in the table show the percentage-effect that can easily be interpreted<br />

(Blossfeld and Rohwer 1995). For example: The risk of a<br />

downward social mobility transition is 1068% higher after an unemployment<br />

spell.<br />

One major result is that spells of unemployment can precede all<br />

kinds of social mobility. Unemployment raises the chance of upward,<br />

downward and lateral social mobility. After an unemployment spell<br />

lateral mobility is more likely than downward mobility, which is more<br />

likely than upward mobility. As all three directions of mobility are<br />

considerably increased, one can conclude that spells of unemployment<br />

mdicate a rather neutral switch in mobility paths. They not only precede<br />

a single direction towards downward mobility and they are not<br />

necessanly the antecedent of a downward Spiral äs suggested by some<br />

versions of exclusion theory.<br />

What are the consequences of cumulative unemployment? Is the<br />

effect of the cumulated length of unemployment spells more singledirectional<br />

than an occasional unemployment spell? The numbers in<br />

Table l give a differentiated answer to this question: Upward mobility<br />

is less likely (-4%) for persons that are characterised by a long record<br />

of unemployment during their career. Employers may use this Information<br />

äs a signal to evaluate that these individuals are less competent<br />

for a higher position. However, it is not necessarily a predictor for a<br />

downward directed career path äs there is no significant effect of cumulative<br />

unemployment on downward mobility. A record of long un-<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 99<br />

Time: 0-12mths.<br />

Time: 12-24mths.<br />

Time: 24-36 mths.<br />

Time: 36-48 mths.<br />

Time: 48-60 mths.<br />

Table 1:<br />

Predictors of social mobility, pce-model, percentage-effects<br />

Time: more than 60 mths.<br />

Unemployment<br />

Cumulated duration of<br />

unemployment<br />

Duration of preceding unemployment<br />

spell<br />

Current level of prestige lower<br />

than prestige level of certificate<br />

Unemployment level<br />

Development of tertiary sector<br />

Formation of companies<br />

Ciosure of companies<br />

Occupational prestige<br />

Labour-entry cohort 1985<br />

Labour force experience<br />

Migration to West Germany<br />

Employment in public service<br />

Woman<br />

With child younger than 6 yrs.<br />

Woman * with child younger<br />

6 yrs.<br />

Upward<br />

mobility<br />

0.0003<br />

0.0004<br />

0.0004<br />

0.0002<br />

0.0004<br />

0.0005<br />

735%**<br />

-4%*<br />

n. s.<br />

4%**<br />

n. s.<br />

8.5%*<br />

1%**<br />

n.s.<br />

-4%**<br />

286%**<br />

-3%**<br />

n.s.<br />

-46%**<br />

n.s.<br />

n.s.<br />

n.s.<br />

Downward<br />

mobility<br />

0.2193<br />

0.3018<br />

0.3011<br />

0.2564<br />

0.2272<br />

0.3237<br />

1068%**<br />

n.s.<br />

-5%**<br />

-3%**<br />

n.s.<br />

-6%*<br />

n.s.<br />

0.9%**<br />

n.s.<br />

44%*<br />

-1%**<br />

n.s.<br />

-64%**<br />

n.s.<br />

n.s.<br />

-31%**<br />

Lateral<br />

mobility<br />

0.0183<br />

0.0249<br />

0.0216<br />

0.0210<br />

0.0209<br />

0.0228<br />

1307%**<br />

n.s.<br />

-7%**<br />

n.s.<br />

-4%*<br />

n.s.<br />

0.6%**<br />

0.4%*<br />

1%*<br />

-30%*<br />

n.s.<br />

23%**<br />

-24%**<br />

n.s.<br />

n.s.<br />

n.s.

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 100<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 101<br />

Table 1 (continued):<br />

Predictors of social mobility, pce-model, percentage-effects<br />

Number of preceding<br />

employment history spells<br />

Log-likelihood<br />

Spells<br />

Events<br />

Upward<br />

mobility<br />

21%**<br />

Downward<br />

mobility<br />

n.s.<br />

-13315<br />

63185<br />

Lateral<br />

mobility<br />

17%**<br />

2431 (480 upward transitions; 638 downward<br />

transitions; 1313 lateral transitions)<br />

** = significant on 1%-level; * = significant on 5%-level; n.s. = not significant<br />

Special Collaborative Centre 1 86: Hast German Career Study<br />

employment can prevent one from getting a better Job, but it is not the<br />

start of a downward slope.<br />

What happens after a long single unemployment spell in the next<br />

Job? Individuais stay longer in their next Job. The figures indicate that<br />

people behave in a more risk-averse manner after a spell of long-term<br />

unemployment: lateral (-7%) äs well äs downward mobility transitions<br />

(-5%) are reduced after single long unemployment spells.<br />

What is the effect for your further career by taking a position below<br />

the level of qualification of your certificate? Is it the start of a<br />

downward slope or can people rebalance resources and positions by<br />

moves of counter-mobility? Data suggest the latter: People with a<br />

lower level of position in relation to the level of their certificate are<br />

more likely to make an upward mobility transition (+4%). They are<br />

also less likely to make downward mobility transitions (-3%). Both results<br />

indicate a tendency of successful counter-mobility to rebalance<br />

resources and positions.<br />

Let us now look at structural influences on mobility in the transformation<br />

process. What is the effect of a rise in the general unemployment<br />

level on individual mobility? The data suggest only a weak effect<br />

of the unemployment level on mobility. There is no significant effect<br />

on vertical mobility, only lateral mobility is slightly reduced (-4%).<br />

Modemisation theory suggests a rise of upward mobility by the<br />

enlargement of the tertiary sector. Indeed data support this optimistic<br />

picture. The chance of individual upward mobility rises with more positions<br />

in the tertiary sector (+8.5%) and the risk of downward mobility<br />

is reduced (-6%). A growth of the tertiary sector in Hast Germany is<br />

connected by a better opportunity structure for individual mobility.<br />

Evolutionary Organisation theory argues that formation and closure<br />

of companies influence individual mobility more than the enlargement<br />

or shrinkage of established companies. Our data on the East<br />

German transformation, which in its initial stage was characterised by<br />

high numbers of formation and closure of companies, support these<br />

suggestions. The formation of new companies offers opportunities for<br />

upward mobility (+1%) and lateral mobility (+0.6%), whereas the closure<br />

of companies leads to a rise of downward mobility and lateral mobility.<br />

The results of the event-history analysis on the effect of unemployment<br />

for mobility with respect to exclusion theory is rather clear<br />

cut: Unemployment is a transitory element of mobility paths. Rather<br />

than determining the direction of social mobility, it is a rather neutral<br />

switch preceding mobility in all directions. The only result that would<br />

fit the usual exclusion discourse is that people with a long record of cumulative<br />

unemployment are less likely to make upward mobility transitions.<br />

In the event history analysis, we also find some hints that<br />

individuals may not simply be the victims of unfavourable conditions;<br />

they try to actively cope with their position. So, after long-term unemployment<br />

spells, they try to hold on to their new Job longer than people<br />

without this experience.<br />

Results of an optimal matching analysis<br />

Before we refute exclusion theory with the empirical results of the<br />

event history analysis, let us be cautious and question the method used.<br />

Maybe there are limits to the method used that prevent us from discovering<br />

exclusionary phenomena: The focus of event-history analysis is

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 102<br />

on the causes of transitions. There are some life-course sociologists<br />

who claim that trajectories are not adequately treated by this kind of<br />

methodology (Abbott and Hrycak 1990). Knowing a lot about transitions<br />

without knowing much about trajectories is like seeing the trees<br />

but not the wood.<br />

Using optimal matching analysis we want to see whether there<br />

are types of careers that show a pattern of exclusion. The focus of this<br />

method is not on single transitions but on whole occupational sequences<br />

and their comparison. For example three sequences of different<br />

persons could look like this: CCUD; CUUD; CCCC, where C<br />

indicates the state "constant Status employment position", U refers to<br />

"unemployed" and D indicates "downward mobility". As each letter is<br />

a measurement of one month the sequence CCCC is an equivalent to<br />

four months in a constant employment position. Optimal matching refers<br />

to a distance measure that is calculated by a comparison of each<br />

sequence with any other. In our example a visual inspection shows that<br />

the sequence CCUD is more similar to the sequence CUUD than to the<br />

sequence CCCC; and CCCC is more similar to CCUD than to CUUD.<br />

With large data sets and long sequences visual inspection is not possible.<br />

Optimal matching computes a matrix of similarity values between<br />

each sequence of the data set. In a second step these distances can be<br />

used in cluster analysis in order to find groups with similar employment<br />

sequences.<br />

In our analysis, states of employment were differentiated into<br />

the following categories: constant Status positions; small downward<br />

mobility positions with a 5-10% lower occupational prestige than the<br />

certificate; large downward mobility positions with a more than 10%<br />

lower occupational prestige, and likewise defined small and large upward<br />

mobility positions. Mobility was measured by comparing the<br />

time-specific prestige score (Ganzeboom and Treiman 1996) with the<br />

prestige score of qualification (according to occupation-specific<br />

graduation or apprenticeship certificate). "Constant Status position"<br />

refers to equivalent values of these two prestige scores. Three states of<br />

non-employment were included: unemployment, studying, and other<br />

kinds of non-employment, which mainly consist of spells of retraining<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 103<br />

or housewife positions. Similarity distances won by optimal matching<br />

algorithms were clustered afterwards with the Ward algorithm. A four<br />

cluster solution was chosen, which showed distinct patterns of career.<br />

Within these four clusters two favourable and two unfavourable<br />

or ambivalent clusters can be seen. The favourable clusters were called<br />

"in constant position" and "the big winners". The unfavourable and the<br />

ambivalent clusters were labelled "the big loss" and "the risky decisions".<br />

The figures two to five show the aggregate time dependent distributions<br />

of our eight states within each cluster.<br />

100%<br />

80%<br />

60%<br />

40%<br />

20%<br />

0%<br />

Figure 2: Career types, cluster 1: In Constant Position<br />

• unemployment<br />

D non-employment<br />

ü studying<br />

• large dow nw ard mobility<br />

• small dow nw ard mobility<br />

D constant position<br />

M large upw ard mobility<br />

D small upw ard mobility<br />

Time in Months<br />

N=880 47.3%<br />

Special Collaborative Centre 186: East German Career Study<br />

The biggest cluster is "in constant position" with 47% of the<br />

sample. The main characteristic of this group is quite permanent employment<br />

without a change of Status. There are few changes in this<br />

cluster: After 10 months, more than 90% of the persons in this cluster<br />

are employed in positions with a prestige Status that is identical or very

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 104<br />

Volume 21Number4/5/62001 105<br />

100%<br />

80%<br />

60%<br />

40%<br />

20%<br />

0%<br />

Figure 3: Career types, cluster 2: The Big Winners<br />

Time in Months<br />

• unemployment<br />

Dnon-employment<br />

Gsludying<br />

large dow nw ard mobility<br />

small dow nw ard mobility<br />

Dconstant Position<br />

N=192 10.3%<br />

Special Collaborative Centre 186: East German Career Study<br />

B large upw ard mobility<br />

Q small upw ard mobility<br />

similar with the qualificational level. On average 1.9% of the persons<br />

of this cluster are unemployed.<br />

The smallest cluster is "the big winners" with 10% of the sample.<br />

Its main characteristic is positions that are considerably higher<br />

than the ones held at the start of the career. At the beginning of the sequence<br />

around 15% of this cluster are studying. These spells of study<br />

are short; after 40 months hardly any students remain in this cluster.<br />

Also "constant position", which was 12% at the beginning, disappears<br />

after 12 months. The percentage of big winners, which could add ten<br />

and more percent to the prestige of their original qualification, rises<br />

from 60% to 97% after 42 months. On average, 3% of the persons in<br />

this cluster are unemployed.<br />

The second biggest cluster is "the big loss" with 24% of the sample.<br />

They had to accept positions that were far below their qualifications<br />

with an occupational prestige level that is ten and more percent<br />

reduced in comparison to the level of their certificate. On average,<br />

people in this group stick to this position for nearly five years within a<br />

100%<br />

r- CO<br />

Figure 4: Career types, cluster 3: The Big Loss<br />

to cn o N-<br />

m

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 106 Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 107<br />

100%<br />

Figure 5: Career types, cluster 4: Risky Decisions<br />

Time in Months<br />

• unempfoyment<br />

D non-employment<br />

Dstudying<br />

• lange dow nw ard mobility<br />

• s mall dow nw ard mobility<br />

P constant position<br />

@ large upw ard mobility<br />

(Ismail upw ard mobility<br />

N=351 18.9%<br />

Special Collaborative Centre 186: East German Career Study<br />

encompassing house-wives äs well äs people in retraining. Most people<br />

in this cluster were either dissatisfied with their original occupational<br />

position or were forced to leave it. The growing proportion of<br />

students, which amounts to 20% after 30 months and keeps to this<br />

level until the end of the observed period, indicates the persons' intentions<br />

to improve the Situation by further education. The proportion of<br />

people in upward and downward mobility positions augments during<br />

the period of observation. One can conclude that not everybody is successful<br />

after leaving bis/ her original occupational position. We labelled<br />

this cluster "risky decision" because the high propensity<br />

towards qualification in this cluster indicates that many transitions are<br />

the result of a conscious decision. However a further characteristic of<br />

this cluster is the fact that the unemployment rate is at 12.6%, the highest<br />

of all clusters.<br />

Spells of unemployment are part of all four types of careers. On<br />

average the duration of unemployment within the career patterns differs<br />

from l .4 months in "the constant position" cluster to 9.5 months in<br />

"the risky decisions" cluster, where unemployment is most prominent.<br />

One cannot say that long-term unemployment is the decisive characteristic<br />

of a whole group of young adults in the transformation process<br />

in East Germany.<br />

Looking at patterns of careers reveals two specific risks for<br />

young people in the transition process: one is seen in the cluster "the<br />

big loss". It is the risk of a loss of tradable human capital, which results<br />

in being stuck in a downgrading of one's position. This is not the risk<br />

of exclusion from the labour market, but the risk of a rather permanent<br />

unfavourable inclusion in the labour market. The second risk is more<br />

ambivalent. It is seen in the cluster "risky decisions". This risk is a<br />

product of market individualisation, which äs a phenomenon was quite<br />

new to East Germans. Unfavourable structural processes force a reaction<br />

of the individual to increase chances on the labour market. In reaction<br />

to this Situation the individual can respond differently with results<br />

differentiating persons even further. As a consequence, some for example<br />

may fail and get stuck in a new spell of unemployment after retraining<br />

while others may succeed and get a much better position after<br />

studying. The cluster "the risky decisions" connects all these rather<br />

different paths; its only connecting theme is individualised risk. Exclusion<br />

from the labour market is a part of the story of the careers in this<br />

cluster, but it is not the whole story, äs exclusion even in this cluster is<br />

temporary and individual reactions to counter exclusionary tendencies<br />

are part of the picture.<br />

We tried to find out which variables could be connected with the<br />

distribution of people among different career clusters. To do this, four<br />

binary logit regressions were run, using the membership of a specific<br />

cluster äs a dependent variable with the value l. The value 0 was coded<br />

for persons belonging to one of the other clusters. The profession<br />

"medical doctors" had such an extreme distribution among the clusters<br />

(none of them in the cluster "big winners", hardly any in the cluster<br />

"big loss") that stable estimations could not be reached. Therefore, this<br />

Professional group was excluded from the logit regressions.<br />

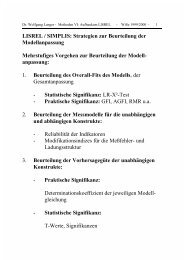

Table 6 presents the results of the logit regressions. The level<br />

and content of the Job related qualifications were the strongest predic-

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 108<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 109<br />

Table 6: Predictors of cluster-distribution (binary logit-models, unstandardized<br />

effect coefficients, without medics)<br />

(N=1616)<br />

woman (ref.: meri)<br />

coh.\990(ref.:coh.<br />

1985)<br />

Professions<br />

/ occupations<br />

social scientists<br />

teacher<br />

agronomists<br />

natural scientists<br />

Production/<br />

consumer goods<br />

construction, fitting<br />

administration<br />

other Services<br />

Constant<br />

-2LL<br />

Pseudo R2<br />

(Mc Fadden P3)<br />

X(df)<br />

Constant<br />

position<br />

(N=646)<br />

-1.461 **<br />

l.HOn.s.<br />

1.234 n. s.<br />

4.744 **<br />

-1.636*<br />

reference cat.<br />

-1.215 n. s.<br />

-1.488*<br />

-1.655*<br />

-1.538 n.s.<br />

-1.333*<br />

2006.166<br />

0.077<br />

168.68(9)**<br />

Big<br />

winners<br />

(N=192)<br />

1.188 n.s.<br />

-1.536*<br />

-1.066 n. s.<br />

1.898 n. s.<br />

-2.785 n.s.<br />

reference cat.<br />

5.082 **<br />

7.075 **<br />

13.639**<br />

6.870 **<br />

-27.77 **<br />

988.447<br />

0.152<br />

179.78(9)**<br />

** = significant on 1%-level; * = signiflcant on 5%-leveI<br />

Big<br />

loss<br />

(N=435)<br />

1.152 n.s.<br />

-1.039 n.s.<br />

-1.066 n.s.<br />

-4.504 **<br />

1.918**<br />

reference cat.<br />

-8.196**<br />

-2.127**<br />

-3.003 **<br />

-7.246 **<br />

-1.587**<br />

1691.319<br />

0.101<br />

191.14(9)**<br />

Special Collaborative Centre 186: Hast German Career Study<br />

Risky<br />

decisions<br />

(N=343)<br />

1.354 n.s.<br />

1.170 n.s.<br />

-1.248 n.s.<br />

-2.890 **<br />

-1.256 n.s.<br />

reference cat.<br />

3.671 **<br />

1.905**<br />

1.333 n.s.<br />

3.694 **<br />

-6.172**<br />

1545.895<br />

0.074<br />

124.80(9)**<br />

tor for the four clusters. Part of this association can be explained by the<br />

different vertical level of degrees held by the members of the professional<br />

and skilled occupational groups. Social scientists, teachers,<br />

agronomists and natural scientists are groups that by definition possess<br />

a university degree, while the other occupational groups are skilled<br />

workers after an apprenticeship. A ceiling effect (S0rensen 1979)<br />

causes less upward mobility for the Professionals that already hold<br />

high prestige Jobs. Therefore, there are less Professionals in the cluster<br />

"big winners" than skilled workers after an apprenticeship. A parallel<br />

logic leads to a smaller risk of apprenticeship trained skilled workers<br />

belonging to the cluster "big loss": As skilled workers already have<br />

Jobs of lower prestige, their likelihood to loose a great proportion of<br />

this prestige is lower than in the professions which have a higher prestige.<br />

Another interesting result of the logit regression is that teachers<br />

are much more likely to belong to the cluster "constant position" and<br />

their probability to be in the "risky decisions" cluster is below other<br />

groups. A similar pattern of a protection from risk holds for men<br />

against women and for professions against skilled occupations. There<br />

seems to be a trade-off between the security of "constant position" and<br />

the discontinuity of "risky decisions". While there is some plausibility<br />

in this account, one has to consider that the "explanatory value", the<br />

pseudo R2, of the clusters "risky decisions" and "constant position" is<br />

quite low.<br />

To sum up the results of the optimal matching analysis: the majority<br />

of young qualified adults in Hast Germany are not excluded from<br />

the labour market. A minority face the risk of rather permanent disqualification<br />

or having to counter temporary exclusion from the labour<br />

market. Spells of unemployment are spread over a wide variety of careers,<br />

but they are most numerous in a "risky decisions" cluster.<br />

Discussion<br />

The empirical analysis of our population of young and qualified Hast<br />

Germans strengthened the thesis of unemployment being a switch in<br />

the labour market. Two perspectives structured the empirical analysis:<br />

on the one hand, there was a focus on single transitions between positions<br />

in the labour market, which showed how social mobility is influenced<br />

by different forms of unemployment. The Status "unemployed"<br />

raises the likelihood for mobility eight to fourteen times (according to<br />

the direction of mobility) in relation to all other employment and nonemployment<br />

statuses. A spell of unemployment is usually not the start<br />

of a downward directed career. As such it is more a rather neutral

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy<br />

switch in career paths. Data analysis showed that the cumulative duration<br />

of all preceding unemployment spells reduces the likelihood of<br />

upward social mobility; however, the likelihood of downward mobility<br />

is not enlarged in this case. Contrary to the supposition of a destabilising<br />

effect of long unemployment spells for the continuity of workrelated<br />

behaviour, analysis shows apreference for risk-avoidance after<br />

unemployment. After experiencing long spells of unemployment, people<br />

tend to hold on to existing Jobs; mobility is avoided. The main result<br />

of the event history analysis is that spells of unemployment in East<br />

Germany are not the first steps of a downward spiralling mobility career.<br />

In the optimal matching analysis the patterning of sequences<br />

was studied. One could argue that there might be a group of persons<br />

with a sequence of permanent unemployment or a combined sequence<br />

of high unemployment and downward mobility. However, the highest<br />

concentration of unemployment within the different career clusters is<br />

not in the "big loss" cluster (with a characteristic of high rates of<br />

downward mobility) but in the "risky decisions" cluster, which is characterised<br />

by many transitions between heterogeneous statuses. Since<br />

unemployment is often part of a "noisy" cluster with many changes, it<br />

is even in the perspective of whole trajectories more a correlation to<br />

Status transitions than a type of trajectory of its own.<br />

These results are important for conceptions of societal exclusion.<br />

From a life-course perspective, the main problem people face in<br />

high unemployment situations is not permanent exclusion, but transitory<br />

exclusion. This empirical perception is an argument against simplistic<br />

conceptions of exclusion which is often wrongly viewed äs a<br />

looming permanent fate. The transitory nature of modern forms of exclusion<br />

is also important for policy issues äs one major aim may be to<br />

structure labour markets in such a way that exclusionary positions can<br />

be left faster.<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 111<br />

is that older age groups and unqualified persons are not part of the<br />

sample. An analysis including higher age groups may find more longterm<br />

unemployment and more transitions from unemployment to<br />

non-employment. However it is not clear, whether these patterns of<br />

un- or non-employment are seen äs illegitimate forms of "exclusion",<br />

äs the meaning of unemployment in higher age groups may be very<br />

different from its meaning in young adulthood. It would also be necessary<br />

to control results for unqualified young people. However, one has<br />

to take into account that structural constraints in the GDR reduced the<br />

overall number of unqualified youngsters to low margins. This fact is<br />

in itself, although to a lesser degree, a characteristic of the schoolwork-transition<br />

in West Germany.<br />

Further research that is needed consists of systematic international<br />

comparisons in this field. Our empirical analysis on the effects<br />

of the transition process for employment careers in East Germany<br />

leads to a rather optimistic evaluation of this process. It is necessary to<br />

compare these results with other transition countries to find out, what<br />

kind of structural components are necessary components for low degrees<br />

of "scarring" after spells of unemployment in young adulthood.<br />

Our analysis showed that quick structural adaptation to new employment<br />

sectors and a high dynamic of Company formations are two<br />

structural processes that produced new opportunities of upward mobility<br />

for young East Germans, which might be a prerequisite for successful<br />

transition processes. There might be other structural components,<br />

e.g. certain combinations of education and labour market Systems such<br />

äs strong apprenticeship Systems (Shavit and Müller 1998; Sackmann<br />

1998) that are relevant factors for the degree of exclusion following<br />

waves of unemployment. As many of these structural variables are<br />

properties of societies and not attributes of individuals, only international<br />

comparisons have a high potential in specifying some of these<br />

causal effects.<br />

Before drawing such general conclusions, we have to discuss<br />

limitations of our data set. Our sample is only representative for two<br />

qualification groups and certain age groups in East Germany. Relevant

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy<br />

112<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 113<br />

Unemployment<br />

Appendix: Variables in the event-history analysis<br />

Cumulated duration of unemployment<br />

Duration of preceding unemployment<br />

spell<br />

Person is in a self-declared state of unemployment<br />

(time-dependent dummy variable).<br />

Accumulation of the length of all unemployment<br />

spells (time dependent variable;<br />

in months).<br />

Time dependent variable; in months.<br />

Ciosure of companies<br />

The number of closures of companies in<br />

the Hast German Bundesland of residence.<br />

For an adjustment to the sizevariance<br />

of the Bundesländer, the average<br />

of absolute formation numbers was<br />

set 100 for each Bundesland. The period<br />

specific variance of closure was expressed<br />

äs percentage deviation of 100. If<br />

the person's residence was outside of<br />

East Germany or if there was a missing<br />

value in the residence calendar, an average<br />

of the deviation values would be attributed.<br />

Time dependent variable.<br />

Current level of prestige lower than prestige<br />

level of certificate<br />

Unemployment level<br />

Difference between the prestige score<br />

(Ganzeboom and Treiman 1996) of<br />

qualification (according to occupationspecificgraduationorapprenticeship<br />

certificate)<br />

minus prestige score of current<br />

Job. Values on interval scale level, positive<br />

values indicating a current position<br />

below qualification, negative values<br />

showing a position above qualification.<br />

Time dependent variable.<br />

East German unemployment rate, quarterly<br />

adjusted time dependent variable.<br />

Occupational prestige<br />

Labour-entry cohort 1985<br />

Labour force experience<br />

Migration to West Germany<br />

SIOPS scores (Ganzeboom and Treiman<br />

1996); time dependent variable.<br />

Reference: entry cohort 1990.<br />

Accumulation of all employment experience;<br />

time dependent variable; in months.<br />

Residence in West Germany, other countries<br />

or not known. Reference: residence<br />

in East Germany. Time dependent<br />

dummy variable.<br />

Development of tertiary sector<br />

Percentage of employment in the East<br />

German tertiary sector, quarterly adjusted<br />

time dependent variable.<br />

Employment in public Service<br />

Reference: employment in private sector.<br />

Time dependent dummy variable.<br />

Formation of companies<br />

_<br />

Absolute number of formation of companies<br />

in East German, divided by 1000;<br />

quarterly adjusted time dependent variible.<br />

Woman<br />

With child younger than 6 yrs.<br />

Reference: man.<br />

Dependent child below age six. Time dependent<br />

dummy variable.<br />

Woman * with child younger 6 yrs.<br />

Interaction term.

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy<br />

References<br />

Abbott, Andrew. (1995) 'Sequence Analysis: New Methods for Old<br />

Ideas.' In Annual Review of Sociology 21: pp. 93-113.<br />

Abbott, Andrew and Hrycak, Alexandra. (1990) 'Measuring resemblance<br />

in sequence data: an optimal matching analysis of musicians'<br />

careers.' In American Journal of Sociology 96: pp. 144-185.<br />

Becker, Roifand Zimmermann, Ekkehard. (1995) 'Statusinkonsistenz<br />

im Lebensverlauf. Eine Längsschnittstudie über Statuslagen von Männern<br />

und Frauen in den Kohorten 1929-31, 1939-41 und 1949-51.' In<br />

Zeitschrift für <strong>Soziologie</strong> 24: pp. 358-373.<br />

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter. (1989) 'Kohortendifferenzierung und Karriereprozeß'.<br />

Frankfurt/M.: Campus.<br />

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter and Rohwer, Götz. (1995) 'Techniques of event<br />

history modeling. New approaches to causal analysis.' Hillsdale: Erlbaum.<br />

Davids, Sabine. (1993) 'Junge Erwachsene ohne anerkannte Berufsausbildung<br />

in den alten und neuen Bundesländern.' In Berufsbildung<br />

in Wissenschaft und Praxis, Heft 2, 22: pp. 11-17.<br />

DiPrete, Thomas A. and Nonnemaker, K. Lynn. (1997) 'Structural<br />

change: Labor market turbulence, and labor market outcomes.' In<br />

American SociologicalReview 62: pp. 386-404.<br />

Eider, Glen H. Jr. (1974) 'Children of the Great Depression.' Chicago:<br />

University of Chicago Press.<br />

Esping-Andersen, G0sta. (ed.) (1993) Changing classes. London:<br />

Sage.<br />

Guo, Guang. (1993) 'Event-history analysis for left-truncated data.' In<br />

Sociological Methodology 23: pp. 217-242.<br />

Halpin, Brendan and Chan, Tak Wing. (1998) 'Class Careers äs Sequences:<br />

An Optimal Matching Analysis of Work-Life Histories.' In<br />

European Sociological Review 14: pp. 111-130.<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 115<br />

Han, Shin-Kap and Moen, Phyllis. (1999) 'Clocking out: Temporal<br />

patterning of retirement.' In American Journal of Sociology 105: pp.<br />

191-236.<br />

Hannan, Michael T. and Carroll, Glenn R. (1992) 'Dynamics of organizational<br />

populations.' New York: Oxford University Press.<br />

Haveman, Heather A. and Cohen, Lisa E. (1994) 'The ecological dynamics<br />

of careers: The impact of organizational founding, dissolution,<br />

and merger on Job mobility.' In American Journal of Sociology 100:<br />

pp. 104-152.<br />

Inkmann, Joachim, Klotz, Stefan and Pohlmeier, Winfried. (1998)<br />

'Permanente Narben oder temporäre Blessuren? Eine Studie über die<br />

langfristigen Folgen eines mißglückten Einstiegs in das Berufsleben<br />

auf der Grundlage von Pseudo-Panel-Daten.' In Pfeiffer, Friedhelm<br />

and Pohlmeier, Winfried (ed.) Qualifikation, Weiterbildung und Arbeitsmarkterfolg.<br />

Baden-Baden: Nomos.<br />

Jahoda, Marie, Lazarsfeld, Paul F. and Zeisel, Hans. (1971) 'Marienthal.<br />

The sociography of an unemployed Community.' Chicago:<br />

Aldine.<br />

Kalleberg, Arne L. and S0rensen, Aage B. (1979) 'The Sociology of<br />

Labor Markets.' In Annual Review of Sociology 5: pp. 351-379.<br />

Kieselbach, Thomas, (ed.) (2000) 'Youth unemployment and social<br />

exclusion: comparison of six European countries.' Opladen: Leske +<br />

Budrich.<br />

Kronauer, Martin, Vogel, Berthold and Gerlach, Frank. (1993) 'Im<br />

Schatten der Arbeitsgesellschaft: Arbeitslose und die Dynamik sozialer<br />

Ausgrenzung.' Frankfurt/M.: Campus.<br />

Mincer, Jacob and Ofek, Haim. (1993) 'Interrupted work careers: depreciation<br />

and restoration of human capital.' In Mincer, Jacob: Collected<br />

essays of Jacob Mincer. Vol. 2: Studies in labor supply.<br />

Aldershot: Elgar. pp. 140-160.

5<br />

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy<br />

Mutz, Gerd, Ludwig-Mayerhofer, Wolfgang, Kroenen, Elmar J., Eder,<br />

Klaus and Bonß, Wolfgang. (1995) Diskontinuierliche Erwerbsverläufe.<br />

Opladen: Leske + Budrich.<br />

Nickel, Hildegard M. and Hüning, Hasso. (1995) Finanzdienstleistungsbeschäftigung<br />

im Umbruch: betriebliche Strategien und individuelle<br />

Handlungsoptionen am Beispiel von Banken und<br />

Versicherungen. Halle.<br />

OECD (1998) 'Getting started, settling in. In OECD Employment Outlook.<br />

Paris: OECD. pp. 81-122.<br />

Pickel, Andreas and Wiesenthal, Helmut. (1997) The grand experiment:<br />

debating shock therapy, transition theory, and the East German<br />

experience. Boulder: Westview.<br />

Rohwer, Götz and Pötter, Ulrich. (1998) TDA Users Manual, Version<br />

l, April 1998, Bochum. Ftp://ftp.stat.ruhr-uni-bochum.de/pub/tda/<br />

tman63/<br />

Sackmann, Reinhold. (1998) Konkurrierende Generationen auf dem<br />

Arbeitsmarkt. Opladen: Westdeutscher.<br />

Scherer, Stefani. (1998) 'Early career patterns - a comparison of the<br />

United Kingdom and Germany.' In Raffe, David, van der Velden, Rolf<br />

and Werquin, Patrick (ed.) Education, the labour market and transitions<br />

in youth: Cross-national perspectives. Edinburgh. S. pp.<br />

333-355.<br />

Schettkat, Ronald. (1992). The Labor Market Dynamics ofEconomic<br />

Restructuring. The United States and Germany in Transition. New<br />

York: Praeger.<br />

Shavit, Yossi and Müller, Walter. (1998) (eds.) From school to work.<br />

Oxford: Oxford University Press.<br />

S0rensen, Aage B. (1979) 'Amodel and ametric on the analysis of the<br />

intrageneratlonal Status attainment process.' In American Journal of<br />

Sociology 85: pp. 361-384.<br />

Spence, Michael. (1973) 'Job Market Signaling.' In Quarterly Journal<br />

ofEconomics 87: pp. 355-374.<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 117<br />

Tuma, Nancy Brandon. (1985) 'Effects of labor market structure on<br />

job shift patterns.' In Heckman, James J. and Singer, Burton (eds.):<br />

longitudinal analysis of labor market dato. Cambridge: University<br />

Press, pp. 327-363.<br />

Weymann, Ansgar, Sackmann, Reinhold and Wingens, Matthias.<br />

n 999) 'Social change and the life course in East Germany.' In International<br />

Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 19: pp. 90-114.<br />

Windzio, Michael. (2001) 'Übergänge und Sequenzen.' In Sackmann,<br />

Reinhold and Wingens, Matthias (eds.) Strukturen des Lebenslaufs.<br />

München: Juventa. (in print)<br />

Zapf, Wolfgang. (1994) Modernisierung, Wohlfahrtsentwicklung und<br />

Transformation. Berlin: sigma.