private-schools-full-report

private-schools-full-report

private-schools-full-report

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The role and impact of <strong>private</strong> <strong>schools</strong> in developing countries: a rigorous review of the evidence<br />

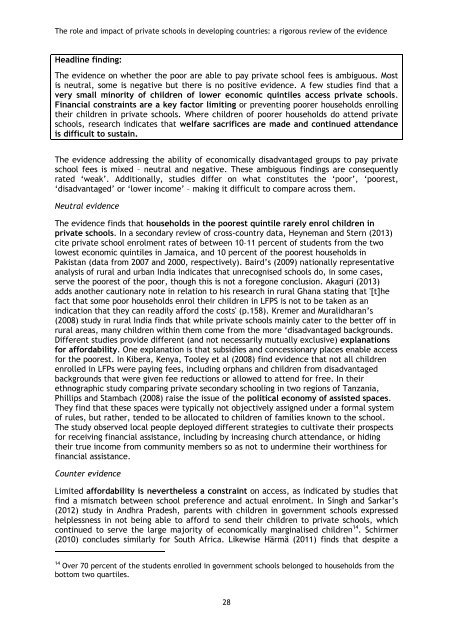

Headline finding:<br />

The evidence on whether the poor are able to pay <strong>private</strong> school fees is ambiguous. Most<br />

is neutral, some is negative but there is no positive evidence. A few studies find that a<br />

very small minority of children of lower economic quintiles access <strong>private</strong> <strong>schools</strong>.<br />

Financial constraints are a key factor limiting or preventing poorer households enrolling<br />

their children in <strong>private</strong> <strong>schools</strong>. Where children of poorer households do attend <strong>private</strong><br />

<strong>schools</strong>, research indicates that welfare sacrifices are made and continued attendance<br />

is difficult to sustain.<br />

The evidence addressing the ability of economically disadvantaged groups to pay <strong>private</strong><br />

school fees is mixed – neutral and negative. These ambiguous findings are consequently<br />

rated ‘weak’. Additionally, studies differ on what constitutes the ‘poor’, ‘poorest,<br />

‘disadvantaged’ or ‘lower income’ – making it difficult to compare across them.<br />

Neutral evidence<br />

The evidence finds that households in the poorest quintile rarely enrol children in<br />

<strong>private</strong> <strong>schools</strong>. In a secondary review of cross-country data, Heyneman and Stern (2013)<br />

cite <strong>private</strong> school enrolment rates of between 10–11 percent of students from the two<br />

lowest economic quintiles in Jamaica, and 10 percent of the poorest households in<br />

Pakistan (data from 2007 and 2000, respectively). Baird’s (2009) nationally representative<br />

analysis of rural and urban India indicates that unrecognised <strong>schools</strong> do, in some cases,<br />

serve the poorest of the poor, though this is not a foregone conclusion. Akaguri (2013)<br />

adds another cautionary note in relation to his research in rural Ghana stating that '[t]he<br />

fact that some poor households enrol their children in LFPS is not to be taken as an<br />

indication that they can readily afford the costs' (p.158). Kremer and Muralidharan’s<br />

(2008) study in rural India finds that while <strong>private</strong> <strong>schools</strong> mainly cater to the better off in<br />

rural areas, many children within them come from the more ‘disadvantaged backgrounds.<br />

Different studies provide different (and not necessarily mutually exclusive) explanations<br />

for affordability. One explanation is that subsidies and concessionary places enable access<br />

for the poorest. In Kibera, Kenya, Tooley et al (2008) find evidence that not all children<br />

enrolled in LFPs were paying fees, including orphans and children from disadvantaged<br />

backgrounds that were given fee reductions or allowed to attend for free. In their<br />

ethnographic study comparing <strong>private</strong> secondary schooling in two regions of Tanzania,<br />

Phillips and Stambach (2008) raise the issue of the political economy of assisted spaces.<br />

They find that these spaces were typically not objectively assigned under a formal system<br />

of rules, but rather, tended to be allocated to children of families known to the school.<br />

The study observed local people deployed different strategies to cultivate their prospects<br />

for receiving financial assistance, including by increasing church attendance, or hiding<br />

their true income from community members so as not to undermine their worthiness for<br />

financial assistance.<br />

Counter evidence<br />

Limited affordability is nevertheless a constraint on access, as indicated by studies that<br />

find a mismatch between school preference and actual enrolment. In Singh and Sarkar’s<br />

(2012) study in Andhra Pradesh, parents with children in government <strong>schools</strong> expressed<br />

helplessness in not being able to afford to send their children to <strong>private</strong> <strong>schools</strong>, which<br />

continued to serve the large majority of economically marginalised children 14 . Schirmer<br />

(2010) concludes similarly for South Africa. Likewise Härmä (2011) finds that despite a<br />

14 Over 70 percent of the students enrolled in government <strong>schools</strong> belonged to households from the<br />

bottom two quartiles.<br />

28