Factors Influencing Visitor's Choices of Urban Destinations in North ...

Factors Influencing Visitor's Choices of Urban Destinations in North ...

Factors Influencing Visitor's Choices of Urban Destinations in North ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Table <strong>of</strong> ContentsI. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................. 1Highlights................................................................................................................................ 1Study Summary........................................................................................................................ 1Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 2Next Steps................................................................................................................................ 3II. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 4III. STUDY OBJECTIVE....................................................................................................... 4IV. METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................... 5A. LITERATURE REVIEW........................................................................................................... 6Introduction............................................................................................................................. 6Key F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs ........................................................................................................................... 7B. SELECTION OF NORTH AMERICAN CITIES ............................................................................ 7C. DEVELOPING AN ATTRACTIONS MATRIX ............................................................................. 8D. ECONOMETRIC APPROACH................................................................................................... 9E. DATA COLLECTION............................................................................................................ 10Visitations Data .................................................................................................................... 10Attractions Data.................................................................................................................... 10Non-Attraction Variables...................................................................................................... 12F. TRAVEL PUBLICATIONS ..................................................................................................... 14Michel<strong>in</strong> ................................................................................................................................ 14Frommer's............................................................................................................................. 15Fodor’s.................................................................................................................................. 15G. MEASURES OF ATTRACTION COUNT .................................................................................. 15Number <strong>of</strong> Attractions...........................................................................................................16Normalized Attractions ......................................................................................................... 16Normalized Share <strong>of</strong> Attractions........................................................................................... 16H. DISCUSSION OF RESULTS ................................................................................................... 17Key F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs ......................................................................................................................... 17I. INTERPRETATION OF REGRESSION RESULTS....................................................................... 21Regression-Specific Conclusions.......................................................................................... 22J. ANALYSIS OF MODEL RESIDUALS...................................................................................... 27K. IMPACT OF ATTRACTION TYPE ON VISITATIONS ................................................................ 30Attraction Elasticities for Ottawa and Toronto .................................................................... 31Market<strong>in</strong>g Budgets Elasticities ............................................................................................. 32

V. OUR RECOMMENDATIONS.......................................................................................... 33VI. NEXT STEPS .................................................................................................................. 34VII. TECHNICAL APPENDIX............................................................................................. 35A. ATTRACTIONS MATRIX EXAMPLES.................................................................................... 35Arts and Culture.................................................................................................................... 35Environment and Built Form ................................................................................................ 35Enterta<strong>in</strong>ment........................................................................................................................ 36Accommodation and Food .................................................................................................... 37B. REGRESSION RESULTS ....................................................................................................... 38C. LITERATURE REVIEW......................................................................................................... 42Tourism Attractiveness Literature ........................................................................................ 42Dest<strong>in</strong>ation Competitiveness Literature ............................................................................... 45<strong>Urban</strong> Tourism Market<strong>in</strong>g Literature................................................................................... 48Tourism Demand/Econometric Modell<strong>in</strong>g Literature .......................................................... 53Bibliography: ........................................................................................................................ 58D. VISITATIONS DATA ............................................................................................................ 60E. STATISTICAL CONCEPTS .................................................................................................... 64

I. Executive SummaryHighlightsThe recent decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> both tourist visits and tourism spend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Ontario has sparked an<strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> evaluat<strong>in</strong>g Ontario's tourist attractions base <strong>of</strong> its major centres, namelyToronto and Ottawa. This <strong>in</strong>cludes assess<strong>in</strong>g the gaps <strong>of</strong> each city's product <strong>of</strong>fer<strong>in</strong>grelative to other <strong>North</strong> American tourist centres. To help understand this issue, theOntario M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Tourism and Recreation (the M<strong>in</strong>istry) <strong>in</strong> partnership with CanadianTourism Commission, Canadian Heritage, and Parks Canada commissioned GlobalInsight to develop an econometric study to quantify the relative importance <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong>factors that <strong>in</strong>fluence tourists’ decisions to visit a particular dest<strong>in</strong>ation with<strong>in</strong> <strong>North</strong>America.The ma<strong>in</strong> objective <strong>of</strong> this study was to estimate the impact <strong>of</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g additionalattractions on <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g tourist visitations to selected <strong>North</strong> American cities and, <strong>in</strong>particular, to Toronto and Ottawa. This study did not consider visitor spend<strong>in</strong>g or length<strong>of</strong> stay. The study objective was achieved by establish<strong>in</strong>g a database <strong>of</strong> the attractions<strong>of</strong>fered to tourists visit<strong>in</strong>g the selected <strong>North</strong> American cities and the number <strong>of</strong> leisurevisitors to each city. Utiliz<strong>in</strong>g this database, Global Insight built a series <strong>of</strong> crosssectionaleconometric models to exam<strong>in</strong>e the deviation among leisure visitation amongthese cities. The estimated coefficients from these models provided an assessment <strong>of</strong> therelative importance <strong>of</strong> various attractions <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the number <strong>of</strong> tourist visitations.Global Insight's major f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong>clude:• Popular enterta<strong>in</strong>ment attractions are the most consistent draw.• Attractions complement and supplement each other.• Rated attractions perform significantly better than non-rated attractions.• A number <strong>of</strong> smaller, mostly Canadian cities receive fewer visitors than theirattractions’ portfolio would warrant.• Cities have the most to ga<strong>in</strong> by diversify<strong>in</strong>g their attraction base.Study SummaryThe first step <strong>in</strong> Global Insight's approach was to conduct a literature review to becomefamiliar with the most recent research regard<strong>in</strong>g the appropriate attractiveness <strong>in</strong>dicatorsto be utilized, the schemes to quantify them for modell<strong>in</strong>g purposes, and the type <strong>of</strong> datathat were used.An attractions matrix was developed to classify the attractions <strong>in</strong>to four <strong>of</strong> the mostobvious categories that are known to draw tourists and are consistent across cities. Thepurpose <strong>of</strong> design<strong>in</strong>g an attractions matrix was to <strong>in</strong>clude a wide range <strong>of</strong> attractions thatare generally believed to stimulate tourist visitations. Us<strong>in</strong>g this attraction matrix, theappropriate attractions data were collected for each city. The total tourist visitations andrelevant non-attractions data were also assembled.1

Global Insight selected a cross-sectional approach to econometric modell<strong>in</strong>g. Thisapproach allowed Global Insight to use a multi-city modell<strong>in</strong>g methodology to exploiteconomies <strong>of</strong> scale by pool<strong>in</strong>g data across 50 cities and estimat<strong>in</strong>g one equation for eachstructural relationship. F<strong>in</strong>ally, Global Insight developed five robust econometric modelswith unique characteristics.The assembled attractions database and five econometric models (via the estimatedcoefficients) provided a wealth <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation concern<strong>in</strong>g the importance <strong>of</strong> each type <strong>of</strong>attraction <strong>in</strong> generat<strong>in</strong>g tourist visits to selected <strong>North</strong> American cities.However, these coefficients were estimated based on a sample <strong>of</strong> 50 cities and providedan average estimate across all cities <strong>in</strong> the sample. Therefore, additional analysis us<strong>in</strong>gthe elasticity concept calculated the implied impacts on Toronto and Ottawa.RecommendationsThe results <strong>of</strong> our study suggest that Toronto and Ottawa would both ga<strong>in</strong> the largestnumber <strong>of</strong> additional visitors by concentrat<strong>in</strong>g their future attractions portfoliodevelopment on the follow<strong>in</strong>g types <strong>of</strong> quality attractions:• Three-star rated amusement parks.• Three-star and one-star shopp<strong>in</strong>g areas.• Three-star-specific structures (i.e. CN Tower or Sky Dome).• They would also benefit from the construction <strong>of</strong> one- and two-star-ratedattractions from a popular enterta<strong>in</strong>ment category (amusement and theme parks,and from cas<strong>in</strong>os).Furthermore, this tourism strategy should also stress the follow<strong>in</strong>g aspects:• Increas<strong>in</strong>g market<strong>in</strong>g budgets <strong>in</strong> both cities. It was found that <strong>in</strong>formationavailable to the traveller prior to departure, as well as the presentation <strong>of</strong> this<strong>in</strong>formation, is important <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the dest<strong>in</strong>ation for many travellers.Furthermore, based on experience <strong>of</strong> several other Canadian cities, Toronto andOttawa could receive substantial returns from <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g their market<strong>in</strong>g budgets.• New attractions need to be added with careful consideration to the support<strong>in</strong>gtourist <strong>in</strong>frastructure needs, such as public transportation and hotels rooms, tomaximize tourists’ overall experience with the new attraction.• The high U.S. population density is a plus <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g visitors to U.S. cities. Thisis another argument for <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the promotion to U.S. markets and adopt<strong>in</strong>gschemes to encourage U.S. visitors to travel north. Jo<strong>in</strong>t air travel/hotel staypackages for U.S. visitors that feature <strong>in</strong>centives, such as reduced attractionadmission fees or food and beverage vouchers, could be utilized <strong>in</strong> this regard.• Complementarity or <strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>of</strong> multiple sites at the dest<strong>in</strong>ation is crucial. Bothcities should be careful to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a balance among a variety <strong>of</strong> attraction typeswhen add<strong>in</strong>g new attractions.2

Next StepsThis project has surfaced a good deal <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation about the types <strong>of</strong> attractions that aresuccessful <strong>in</strong> attract<strong>in</strong>g visitors to <strong>North</strong> American cities. However, by design, it hasfocused solely on the number <strong>of</strong> additional leisure visitors that could be enticed with anew attraction <strong>in</strong> Toronto or Ottawa. Notably, it has not considered visitor spend orlength <strong>of</strong> stay. Nor has it shed light on the behaviour <strong>of</strong> local residents to the addition <strong>of</strong>new attractions. It has ignored <strong>in</strong>dividuals visit<strong>in</strong>g friends and relatives and bus<strong>in</strong>esstravellers who <strong>in</strong>dulge <strong>in</strong> non-bus<strong>in</strong>ess activities dur<strong>in</strong>g their stay. Consequently, there isa range <strong>of</strong> potential follow-on analysis that could be considered as the M<strong>in</strong>istryformulates future plans to br<strong>in</strong>g more visitors to Ontario. Some <strong>of</strong> the possible extensionsto this project <strong>in</strong>clude:• Address<strong>in</strong>g behavioural differences among visitor segments such as bus<strong>in</strong>esstravellers, travellers visit<strong>in</strong>g friends and relatives, and the <strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>of</strong>convention and bus<strong>in</strong>ess travellers with non-bus<strong>in</strong>ess attractions.• Separat<strong>in</strong>g the tourist visitations data to look at the preferences <strong>of</strong> visitors fromdifferent orig<strong>in</strong>s (Europe, <strong>North</strong> America, Lat<strong>in</strong> America or Asia).• Exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g visitor spend<strong>in</strong>g patters and how this affects overall tourist revenue.• Study<strong>in</strong>g the length <strong>of</strong> visits and the impact on the tourist visitations.• Exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the actual experience <strong>of</strong> cities that have added the attraction types thatmight be considered by Toronto and Ottawa.3

II.IntroductionTourism is a vital element <strong>of</strong> Ontario’s highly diversified and dynamic economy. Thetourism sector accounts for roughly 4.5% <strong>of</strong> Ontario's GDP and employment. However,recent external shocks have thrown this sector <strong>in</strong>to a sharp decl<strong>in</strong>e. The l<strong>in</strong>ger<strong>in</strong>g impact<strong>of</strong> 9/11, the recent U.S. recession, appreciation <strong>of</strong> the Canadian dollar, military<strong>in</strong>tervention <strong>in</strong> Iraq, and SARS have all contributed to a sharp fall <strong>in</strong> visitors to Ontario’smajor metropolitan centres <strong>in</strong> 2003. Global Insight estimates that both visitor arrivals toOntario and total visitor spend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Ontario decl<strong>in</strong>ed by 10% <strong>in</strong> 2003 1 .Fortunately, Ontario’s major urban centres <strong>of</strong>fer a remarkably broad range <strong>of</strong> featuresthat will help <strong>of</strong>fset these negative shocks and rebuilt tourism to the region.Unfortunately, the significance <strong>of</strong> any particular feature or comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> features ontravel demand is not well understood. Consequently, tourism promotion strategies anddecisions related to the development <strong>of</strong> the attraction portfolio <strong>in</strong> Ontario are made withonly a partial understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the impact these decisions may have on prospectivevisitors.The Ontario M<strong>in</strong>istry <strong>of</strong> Tourism and Recreation (the M<strong>in</strong>istry) <strong>in</strong> partnership with theCanadian Tourism Commission, Canadian Heritage, and Parks Canada commissionedGlobal Insight to develop an econometric model to quantify the relative importance <strong>of</strong> therange <strong>of</strong> attractions that <strong>in</strong>fluence tourists’ decisions to visit a particular dest<strong>in</strong>ationwith<strong>in</strong> <strong>North</strong> America. This model will be used to better understand the attractiveness <strong>of</strong>Toronto and Ottawa as visitor dest<strong>in</strong>ations relative to compet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>North</strong> Americandest<strong>in</strong>ations and to facilitate the decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g process <strong>of</strong> the M<strong>in</strong>istry as it developsguidel<strong>in</strong>es to encourage visitors to come to Ontario.In particular, the econometric model or models will help to:• Assess gaps <strong>in</strong> the product <strong>of</strong>fer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> particular tourism centres;• Quantify the potential returns from proposed product development;• Identify synergies between particular mixes <strong>of</strong> features; and• Establish objective criteria for product development priorities.III.Study ObjectiveThe ma<strong>in</strong> objective <strong>of</strong> this study was to estimate the impact <strong>of</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g additionalattractions on <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g tourist visitations to the selected <strong>North</strong> American cities. Thisstudy did not consider visitor spend or length <strong>of</strong> stay. The objective was achieved by:• Establish<strong>in</strong>g a database <strong>of</strong> the attractions <strong>of</strong>fered to tourists visit<strong>in</strong>g the selected<strong>North</strong> American cities and the number <strong>of</strong> leisure visitors to each city.• Utiliz<strong>in</strong>g this database to build a series <strong>of</strong> cross-sectional econometric models toexam<strong>in</strong>e the deviation among leisure visitation among these cities. The estimated1 Global Insight estimates that <strong>in</strong> 2004, visitor arrivals to Ontario will see a significant growth <strong>of</strong> 13%,while the total visitor spend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Ontario will experience a modest growth <strong>of</strong> 5%.4

IV.coefficients from these models provided an assessment <strong>of</strong> the relative importance<strong>of</strong> various attractions <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the number <strong>of</strong> tourist visitations.MethodologyGlobal Insight's approach to this project was to <strong>in</strong>itially conduct a literature review tobecome familiar with the most recent research regard<strong>in</strong>g the appropriate attractiveness<strong>in</strong>dicators to be utilized, the schemes to quantify them for modell<strong>in</strong>g purposes, and thetype <strong>of</strong> data that were used.Subsequently, Global Insight selected a sample <strong>of</strong> 50 major metropolitan areas <strong>in</strong> <strong>North</strong>America with the population size <strong>of</strong> 500,000 or more to be covered <strong>in</strong> the attractionsdatabase. Ten <strong>of</strong> these cities were <strong>in</strong> Canada, while 40 were <strong>in</strong> the United States. Thesecities were those that <strong>of</strong>fered a broad range <strong>of</strong> attractions by themselves. Global Insightdid not <strong>in</strong>clude cities that developed a large visitation count by virtue <strong>of</strong> one ma<strong>in</strong> type <strong>of</strong>attraction or that relied on attractions that were close to, but not a part <strong>of</strong>, themetropolitan area itself.Then, Global Insight developed an attractions matrix to classify the attractions <strong>in</strong>to fourcategories that are recognized to draw tourists and consistent across cities. Us<strong>in</strong>g thisattraction matrix, the appropriate attractions data were collected for each city. The totalleisure tourist visitations and additional non-attractions data were also assembled.Travel reviews published by Michel<strong>in</strong>, Frommer's, and Fodor's were selected <strong>in</strong> order topopulate the attractions matrix with relevant data for each city. These publicationsprovided Global Insight with the wealth <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation about various types <strong>of</strong> attractionsand their quality rat<strong>in</strong>gs across the 50 <strong>North</strong> American cities.Because city attraction portfolios change slowly over time, Global Insight selected across-sectional approach to econometric modell<strong>in</strong>g. This approach allowed Global Insightto pool data across the 50 cities and estimate one equation for each structural relationship.The methodology section <strong>of</strong> the report will review tasks one through seven. Tasks eightand n<strong>in</strong>e will be discussed <strong>in</strong> the third section <strong>of</strong> the report “Discussion <strong>of</strong> Results.”Table 1: Required TasksTask # Description1 Literature Review2 Select <strong>North</strong> American Cities3 Implement an Attraction Classification Scheme4 Choose an Econometric Approach5 For Each City, Collect Travel Visitation Data,Attraction Data, and Non-attraction Data6 Select Travel Publications7 Select Measures <strong>of</strong> Attraction Count8 Construct Economic Model or Models9 Identify High-Return AttractionsSource: Global Insight, Inc.5

A. Literature ReviewIntroductionGlobal Insight conducted a literature review <strong>in</strong> order to complement Global Insight'sunderstand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> past efforts to evaluate the attractiveness characteristics <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualcities. The literature review focuses on identify<strong>in</strong>g key articles <strong>in</strong> the tourism literatureand describ<strong>in</strong>g the ma<strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from these articles. Many <strong>of</strong> the articles Global Insightreviewed were survey articles that summarized the range <strong>of</strong> current and past researchreported. In this way, Global Insight reviewed key elements <strong>of</strong> the extensive set <strong>of</strong>literature published on tourism attraction over the past decades. Information gleaned fromthis review <strong>in</strong>fluenced the structure <strong>of</strong> our empirical modell<strong>in</strong>g work <strong>in</strong> that portion <strong>of</strong> theproject. Global Insight's research <strong>in</strong>cluded articles from the follow<strong>in</strong>g four categories <strong>of</strong>tourism-related research:• Tourism Attractiveness Literature;• Dest<strong>in</strong>ation Competitiveness Literature;• <strong>Urban</strong> Tourism Market<strong>in</strong>g Literature;• Tourism Demand/Econometric Modell<strong>in</strong>g Literature.Tourism Attractiveness Literature focuses on a discussion <strong>of</strong> factors that <strong>in</strong>fluence theattractiveness <strong>of</strong> the dest<strong>in</strong>ation such as culture, <strong>in</strong>frastructure, price levels, and attitudestowards tourists. More recently, some articles def<strong>in</strong>e “tourist attraction systems” thatconsider how these factors <strong>in</strong>fluence tourists through market<strong>in</strong>g and promotion <strong>of</strong> thesite.Dest<strong>in</strong>ation Competitiveness Literature describes key foundations for develop<strong>in</strong>g acomprehensive tourism model. Not only the core resources and attractors <strong>of</strong> thedest<strong>in</strong>ation are important, but also elements such as dest<strong>in</strong>ation management, dest<strong>in</strong>ationpolicy, and contribut<strong>in</strong>g macro and microenvironment factors. “Competitiveness <strong>in</strong> thetourism sector is def<strong>in</strong>ed as the ability <strong>of</strong> the tourism market environment and conditions,tourism resources, tourism human resources, and tourism <strong>in</strong>frastructure <strong>in</strong> a country tocreate an added value and <strong>in</strong>crease national wealth. That is to say, the competitiveness <strong>in</strong>the tourism sector is not only a measure <strong>of</strong> potential ability, but also an evaluation <strong>of</strong>present ability and tourism performance.” 2<strong>Urban</strong> Tourism Market<strong>in</strong>g Literature exam<strong>in</strong>es the market<strong>in</strong>g strategies undertaken byurban authorities and tourism marketers. “A dest<strong>in</strong>ation that has a tourism vision, sharesthis vision among all stakeholders, understands both its strengths and its weaknesses,develops an appropriate market<strong>in</strong>g strategy, and implements it successfully may be morecompetitive than one which has never exam<strong>in</strong>ed the role that tourism is expected to play3<strong>in</strong> its economic and social development.”Tourism Demand/Econometric Modell<strong>in</strong>g Literature uses econometric techniques andmodels to forecast tourism demand. Econometric techniques range from statistical time2 Kim (2000).3 Dwyer and Kim (2001).6

series, simple autoregressive and “no change” models, to more complicated errorcorrectionmodels.Key F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsThe most common, recurr<strong>in</strong>g themes evident <strong>in</strong> the literature review are identified <strong>in</strong> thefollow<strong>in</strong>g summary po<strong>in</strong>ts 4 . The key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs highlight the importance <strong>of</strong>:Promotion: Information available to the traveller prior to his departure, and thepresentation <strong>of</strong> this <strong>in</strong>formation, is important <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the dest<strong>in</strong>ation for manytravellers.Quality: The tourist is search<strong>in</strong>g for a high-quality travel experience. Quality is shapedby all elements affect<strong>in</strong>g the tourist at the site, and it is primarily by <strong>of</strong>fer<strong>in</strong>g a highqualityexperience that dest<strong>in</strong>ations compete.Enterta<strong>in</strong>ment: The “enterta<strong>in</strong>ment value” <strong>of</strong> a dest<strong>in</strong>ation is important to manytourists—even at museums and other “cultural” sites.Shopp<strong>in</strong>g Atmosphere: Shopp<strong>in</strong>g is an important element to a tourist, but it must help todeliver the “atmosphere” <strong>of</strong> the dest<strong>in</strong>ation to the visitor.Tourism Infrastructure: The dest<strong>in</strong>ation’s tourism <strong>in</strong>frastructure (generally speak<strong>in</strong>g,elements that ease the tourists access to the dest<strong>in</strong>ation—hotels, transportation, attitudes<strong>of</strong> locals towards tourists, etc.) is a very important contributor to the tourist’s overallexperience.Multiple Attractions: Complementary or <strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>of</strong> multiple sites at the dest<strong>in</strong>ationis important.B. Selection <strong>of</strong> <strong>North</strong> American CitiesFor the purpose <strong>of</strong> this study, Global Insight selected the sample <strong>of</strong> 50 majormetropolitan areas 5 (MSA), <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g 40 U.S. and 10 Canadian cities. The selected citieseach <strong>of</strong>fer a broad range <strong>of</strong> attractions by themselves, and do not rely on attractions nearthat are not a part <strong>of</strong> the metropolitan area. All 50 cities have a population <strong>of</strong> 500,000 ormore. Global Insight did not consider a number <strong>of</strong> cities that develop a significantamount <strong>of</strong> leisure visitation by virtue <strong>of</strong> one ma<strong>in</strong> type <strong>of</strong> attraction.4 Please refer to the Technical Appendix for a full coverage <strong>of</strong> Literature Review.5 In Canada, these areas are called census metropolitan areas (CMA).7

Canada (10)TorontoMontrealVancouverOttawa-HullCalgaryEdmontonQuebecW<strong>in</strong>nipegVictoriaHalifaxTable 2: List <strong>of</strong> Selected <strong>North</strong> American CitiesUnited States (40)OrlandoLos AngelesMilwaukeeLas VegasSeattleTampaAust<strong>in</strong>New York CityPortlandBostonSan DiegoIndianapolisColumbusChicagoHoustonDetroitSan AntonioDallasSt. LouisWash<strong>in</strong>gtonPhiladelphiaAtlantaNew OrleansMiamiKansas CitySalt Lake CityBaltimoreSan FranciscoNashvilleC<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>natiFort LauderaleOklahoma CityM<strong>in</strong>neapolisClevelandSacramentoDenverPittsburghCharlottePhoenixMemphisC. Develop<strong>in</strong>g an Attractions MatrixThe purpose <strong>of</strong> this study was to quantify the relative importance <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> factorsthat <strong>in</strong>fluence tourists' decisions to visit a particular dest<strong>in</strong>ation with<strong>in</strong> <strong>North</strong> America. Inorder to achieve this goal, Global Insight developed an empirical scheme describ<strong>in</strong>g theattractions <strong>of</strong>fered by each city. Global Insight's scheme also <strong>in</strong>corporated a comb<strong>in</strong>ation<strong>of</strong> the quantity <strong>of</strong> attraction (i.e. number <strong>of</strong> amusement parks) and the quality <strong>of</strong> theattraction (i.e. rat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> an amusement park). Global Insight collected the city attractiondata <strong>in</strong> concordance with the structure <strong>of</strong> the attractions matrix.The attractions base can be def<strong>in</strong>ed as broadly as possible. The purpose <strong>of</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g anattractions matrix is to <strong>in</strong>clude a wide range <strong>of</strong> attractions that are generally believed tostimulate tourist visitations. Therefore, a tourist attractions matrix was constructed for thefour most obvious categories that are known to draw tourists and are consistent acrosscities: Arts and Culture; Environment and Built Form; Enterta<strong>in</strong>ment; andAccommodation and Food. Each attraction category <strong>in</strong>cluded several sub-categories,which were subsequently broken down to specific types <strong>of</strong> attractions. Once aga<strong>in</strong>, thesesub-categories and specific types <strong>of</strong> attractions are consistent across cities.8

Arts & Culture Museums Historymuseums Historic sites Other Visual Arts Art galleries Art-relatedevents &festivalsTable 3: Attractions Matrix 6Environment &Built Form Physical Sett<strong>in</strong>g Waterfronts &beaches Other geographicfeatures <strong>Urban</strong> Amenities Parks & greenspaces Shopp<strong>in</strong>g areas Bus<strong>in</strong>essdistricts Built Form General build<strong>in</strong>garchitecture Specificstructures <strong>of</strong><strong>in</strong>terestEnterta<strong>in</strong>ment PopularEnterta<strong>in</strong>ment Amusements &theme parks Spectator sports Cas<strong>in</strong>os Participationsportsopportunities Events &festivals Night clubs CulturalEnterta<strong>in</strong>ment Opera Theater Ballet OrchestraAccommodation& Food Accommodation Luxury hotelrooms Food High-endrestaurants Food-relatedevents & festivals Range <strong>of</strong>restaurantsD. Econometric ApproachBefore turn<strong>in</strong>g to the discussion <strong>of</strong> how the knowledge base represented by the databaseand model will be leveraged to provide a conceptual framework and practical guidancefor the development <strong>of</strong> a tourism strategy, it will be useful to briefly consider the basicelements <strong>of</strong> our technical approach.Because attraction portfolios tend to change slowly over time, Global Insight took theapproach to pool data across 50 <strong>North</strong> American cities and estimated a series <strong>of</strong> equationsrelat<strong>in</strong>g the city attraction portfolios to leisure visitations.In cases where there were miss<strong>in</strong>g data for certa<strong>in</strong> types <strong>of</strong> attractions, this econometricapproach allowed Global Insight to obta<strong>in</strong> robust results. More substantively, the crosssectionalsample means that the model reflects a much greater range <strong>of</strong> tourismexperience than possible <strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle-city approach. Furthermore, the methodology permitsmore credible measures <strong>of</strong> potential changes <strong>in</strong> future attractions or tourism promotional<strong>in</strong>itiatives outside the range <strong>of</strong> the historical experience <strong>in</strong> the data for a s<strong>in</strong>gle city.With the guidance from the literature review and collected attraction and non-attractiondata, a series <strong>of</strong> cross-sectional models were estimated. These models estimated thenumber <strong>of</strong> leisure tourist visitations as a function <strong>of</strong> the attractions def<strong>in</strong>ed for each <strong>of</strong> theselected <strong>North</strong> American cities <strong>in</strong> 2002. Non-attraction variables were also <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong>the model for the same period <strong>of</strong> time.The structure <strong>of</strong> the model enabled Global Insight to identify and rank the relative return<strong>of</strong>fered by each type <strong>of</strong> attraction <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> visitations it can generate.Based on these observations, Global Insight was able to identify a subset <strong>of</strong> the most6 Please refer to Appendix A for a detailed category list<strong>in</strong>g.9

easonable attraction types for Toronto and Ottawa to pursue <strong>in</strong> expand<strong>in</strong>g its attractionportfolio to enhance future visitations.E. Data CollectionThe data required for this study can be classified <strong>in</strong>to three categories: visitations data,attraction data, and non-attraction data.Visitations DataThe visitations data Global Insight analyzed focused on tourists travell<strong>in</strong>g for leisure(exclud<strong>in</strong>g trips to visit friends and relatives) and travell<strong>in</strong>g at least 50 miles from theirorig<strong>in</strong>. These visits were totalled regardless <strong>of</strong> the visitor source—whether domestic or<strong>in</strong>ternational. The data sources <strong>in</strong>cluded D.K. Shifflet, the Office <strong>of</strong> Travel and TourismIndustries, and Statistics Canada. Global Insight focused only on the most recent year <strong>of</strong>data, which was 2002. (Please see the Technical Appendix for more <strong>in</strong>formation aboutthe visitations data.)Attractions DataFor the purpose <strong>of</strong> this study, the attractions database was created for each selected <strong>North</strong>American city. The attractions data were the <strong>in</strong>dependent (or explanatory) variables <strong>in</strong>our regression analysis. The database conta<strong>in</strong>ed (1) the total count <strong>of</strong> attractions (i.e. thenumber <strong>of</strong> amusement parks); and (2) the quality-rated attractions for each category, subcategory,and type <strong>of</strong> attraction.S<strong>in</strong>ce some travel publications 7 provided consistent quality rat<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> attractions acrossthe selected <strong>North</strong> American cities, Global Insight utilized these rat<strong>in</strong>gs to rank touristattractions. The quality rat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> attractions ranged from a no-star to a three-star rat<strong>in</strong>g,with no star <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g a “worth see<strong>in</strong>g” attraction (value <strong>of</strong> zero was assigned to this type<strong>of</strong> attraction) and a three-star <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g a “highly recommended” attraction (value <strong>of</strong>three was assigned to this type <strong>of</strong> attraction). To capture the quality rat<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> touristattractions <strong>in</strong> the database, the value <strong>of</strong> three was assigned to a three-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, value <strong>of</strong>two to a two-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, value <strong>of</strong> one to a one-star rat<strong>in</strong>g and value <strong>of</strong> zero to the type <strong>of</strong>attraction that was not rated by either travel guide, but is considered worth see<strong>in</strong>g. Theattractions were totalled for each category, sub-category, and type <strong>of</strong> attraction. The totalswere calculated for the total count <strong>of</strong> attractions, three-star, two-star-, and one-star-ratedattractions. For each city, a summary sheet was also <strong>in</strong>cluded to show the total count, thetotal count <strong>of</strong> three-star, two-star, and one-star-rated attractions across all categories.Tourist visitations data was separately regressed on the attraction categories, theattraction sub-categories and the specific types <strong>of</strong> attractions. For example, the number <strong>of</strong>tourist visitations was regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> attractions <strong>in</strong> the arts and culturecategory. Secondly, the visitations data was regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> museum subcategories.F<strong>in</strong>ally, tourist arrivals were regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> history museums.7 Please see “Publications” section <strong>of</strong> the report for more <strong>in</strong>formation about these travel publication sandhow they were selected.10

The tourist visitations data was also regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> quality-rated attractions(three-, two-, or one-star rated) us<strong>in</strong>g the attractions categories, the attractions subcategories,and the specific types <strong>of</strong> attractions. For example, the number <strong>of</strong> touristvisitations was regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> three-star-rated attractions <strong>in</strong> the arts andculture category. Secondly, the visitations data was regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> three-starratedmuseums. F<strong>in</strong>ally, tourist arrivals were regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> three-star-ratedhistory museums.Table 4: City Attractiveness Database for New York (Extract)Count Arts&Culture MuseumsGeneral HistoryMuseumsHistoric SitesOtherThemedMuseumsVisualArtsArtGalleries2 1 2 12 1 2 32 0 30 0 31 3 22 0 22 0 11 0110222222Arts relatedevents andfestivalsTotal Count<strong>of</strong> Attractionsby Category 34 27 2 17 8 7 7 0Total number<strong>of</strong> attractionswith a threestarrat<strong>in</strong>g 4 1 0 0 1 3 3 0Total number<strong>of</strong> attractionswith a twostarrat<strong>in</strong>g 15 13 2 9 2 2 2 0Total number<strong>of</strong> attractionswith a onestarrat<strong>in</strong>g 8 6 0 6 0 2 2 0ExamplesThe NY HistoricalSocietyEllis IslandImmigrationmuseum;the SouthStreetSouth Street SeaportSeaport; Lower Museum;Manhattan; Lower EastDowntown and Sidethe TenementNeighborhoods; Museum;East Village; AmericanSoho; Cathedral Museum <strong>of</strong><strong>of</strong> St. John the NaturalDiv<strong>in</strong>e HistoryMuseumforAfricanArt;Museum<strong>of</strong>ModernArtSource: Global Insight, Inc.11

Table 5: Summary Sheet for New YorkNEY Overall score - Conde Naste Traveller 82.70%Overall score - Michel<strong>in</strong> 3Total count <strong>of</strong> attractions 294Number <strong>of</strong> attractions with *** rat<strong>in</strong>g 61Number <strong>of</strong> attractions with ** rat<strong>in</strong>g 81Number <strong>of</strong> attractions with * rat<strong>in</strong>g 23Public Transportation/Infrastructure Overall score - Places Rated Almanac 99.43%Large hub (yes-1, no-0) 1International airport, nonstop<strong>in</strong>ternational dest<strong>in</strong>ation (yes-1, no-0) 1Number <strong>of</strong> Miss<strong>in</strong>g Attractions (tcma) 7Source: Global Insight, Inc.Non-Attraction VariablesThe number <strong>of</strong> visits was not only regressed on different types <strong>of</strong> attractions, but also ona variety <strong>of</strong> non-attraction variables. These variables were <strong>in</strong>cluded to control forvariations <strong>in</strong> other visitor <strong>in</strong>fluences from city to city; and to <strong>in</strong>clude measures <strong>of</strong> tourism<strong>in</strong>frastructure that also varied among the 50 cities. The literature review had suggestedthe importance that <strong>in</strong>frastructure plays <strong>in</strong> attract<strong>in</strong>g tourists and contribut<strong>in</strong>g to theoverall experience. Consequently, Global Insight added measures <strong>of</strong> hotel property count,hotel room count, and public transportation score to the modell<strong>in</strong>g process.A number <strong>of</strong> these variables ultimately proved useful <strong>in</strong> our analysis, while others didnot. The detailed discussion <strong>of</strong> our modell<strong>in</strong>g results will refocus on the usefulness <strong>of</strong>these non-attraction variables.Table 6: Non-Attraction VariablesType <strong>of</strong> VariableOverall City ScoreFilter Variable for a Large Hub AirportPopulation by State or Prov<strong>in</strong>ce Total Count <strong>of</strong> Miss<strong>in</strong>g AttractionsHotel Room CountPopulation DensityProperty CountProximity to Major Metro AreasPublic Transportation ScoreCity-by-city Market<strong>in</strong>g BudgetsFilter Variable for International AirportOverall City Score: The overall city score captures the quality rat<strong>in</strong>g for a particularcity. This variable was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from Michel<strong>in</strong>'s travel guide, which provided aconsistent rank<strong>in</strong>g for all 50 cities. The overall score ranges from a three-star rat<strong>in</strong>g to aone-star rat<strong>in</strong>g. Global Insight assumed that a higher overall score would <strong>in</strong>crease thenumber <strong>of</strong> tourists.Population by State or Prov<strong>in</strong>ce: Population data was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from Statistics Canadaand Global Insight databanks. The data were obta<strong>in</strong>ed for 2002.12

Hotel Room Count and Hotel Property Count: These are supply-side variables, whichmeasure the number <strong>of</strong> hotel rooms and hotel properties available <strong>in</strong> each city. Thenumber <strong>of</strong> rooms or properties is generally positively correlated with visitations.Although the data were available from 1998 to 2002, Global Insight used a five-yearaverage.Public Transportation Score: Many <strong>of</strong> the articles exam<strong>in</strong>ed by Global Insight as part<strong>of</strong> the literature review noted the importance <strong>of</strong> an efficient transportation system <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g the urban tourism experience. Us<strong>in</strong>g data published <strong>in</strong> the Places RatedAlmanac for the year 2000, Global Insight was able to <strong>in</strong>corporate the <strong>in</strong>fluence thisvariable has on urban visitations. Places Rated Almanac provides a public transportationscore for 354 <strong>North</strong> American metro areas. The score is based on three weighted factors:commute time (30%), connectivity (60%), and centrality (10%).Commute Time(30%)Table 7: Public Transportation ScoreLeaders:Connectivity(60%)Leaders:Centrality (10%)Leaders:Round-trip commut<strong>in</strong>g time + local publictransit mileage.Small and mid-sized Canadian metro areas(Edmonton, Halifax).Comb<strong>in</strong>es national highways, passenger raildepartures, and nonstop airl<strong>in</strong>e dest<strong>in</strong>ations.New York, Chicago, Toronto, and LosAngeles.Metropolitan proximity to other metro areas.Memphis, C<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>nati, and Indianapolis.Source: Places Rated Almanac, 2000.Filter Variable for International Airports: This variable was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the PlacesRated Almanac publication. If the city had an <strong>in</strong>ternational airport where non-stop<strong>in</strong>ternational flights were available, the value <strong>of</strong> “1” was assigned. If the opposite wastrue, the value <strong>of</strong> “0” was given. Our hypothesis is that cities with <strong>in</strong>ternational airportsattract more tourists than cities without these types <strong>of</strong> airports.Filter Variable for a Large Hub Airports: This variable was obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the PlacesRated Almanac publication. If the city had a large hub airport, the value <strong>of</strong> “1” wasassigned. If the opposite was true, the value <strong>of</strong> “0” was given. Places Rated Almanacdef<strong>in</strong>es large hub airports as those attract<strong>in</strong>g at least 1% <strong>of</strong> total tourist flows for thecountry. Our hypothesis is that cities with large hub airports should be positivelycorrelated with city visitations.Total Count <strong>of</strong> Miss<strong>in</strong>g Attractions: This variable was constructed us<strong>in</strong>g the data fromthe attractions database. An attraction was considered miss<strong>in</strong>g if it was not mentioned <strong>in</strong>any <strong>of</strong> the travel publications. The value “1” was assigned to miss<strong>in</strong>g attractions, and thevalue “0” was assigned to attractions that were present <strong>in</strong> the database. Our hypothesis isthat a larger number <strong>of</strong> miss<strong>in</strong>g attractions suggests a less diverse attraction portfolio <strong>in</strong> aparticular city, reduc<strong>in</strong>g the number <strong>of</strong> tourist visitations to a city.13

Population Density: A higher population density should contribute to a highertourist count. The average population density for the United States is 29.4 residents persquare kilometre, while the average density for Canadian cities is only 3.1. Thepopulation density data were obta<strong>in</strong>ed from Statistics Canada.Proximity to Population Centres: This variable was constructed to measure theproximity <strong>of</strong> each city to population centres. For the eastern block <strong>of</strong> cities, the distance<strong>in</strong> miles was measured relative to New York City, and for the western block <strong>of</strong> citiesrelative to Santa Barbara. As the distance from major metro areas <strong>in</strong>creases (<strong>in</strong> our caserelative to New York City and Santa Barbara), the number <strong>of</strong> tourist visitations shoulddecl<strong>in</strong>e.City-by-city Market<strong>in</strong>g Budgets: City-by-city budgets were available from theInternational Association <strong>of</strong> Conventions and Visitor Bureaus (IACVB) survey 8 . Not all<strong>of</strong> the 50 cities responded to this survey, and this is why the sample <strong>of</strong> only 33 cities wasconsidered. The data were available for 2003. Our hypothesis is that a larger market<strong>in</strong>gbudget should <strong>in</strong>crease the number <strong>of</strong> tourist visits to a city.Table 8: List <strong>of</strong> 33 <strong>North</strong> American CitiesU.S. CitiesCanadian CitiesPhoenix, AZ Chicago, IL New York City, NY Aust<strong>in</strong>, TX Montreal, QCSan Diego, CA Indianapolis, IN Columbus, OH Salt Lake City, UT Vancouver, BCSan Francisco, CA Detroit, MI Cleveland, OH Seattle, WA Calgary, ABLos Angeles, CA M<strong>in</strong>neapolis, MN Oklahoma City, OK Milwaukee, WI Quebec, QCDenver, CO Kansas City, MN Philadelphia, PA Victoria, BCOrlando, FL St. Louis, MO Pittsburgh, PATampa, FL Charlotte, NC Nashville, TNAtlanta, GA Las Vegas, NV San Antonio, TXF. Travel PublicationsTravel publications by Michel<strong>in</strong>, Frommer's, and Fodor's were used to populate theattractions matrix with relevant data for each city. These publications provided GlobalInsight with the wealth <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation about various types <strong>of</strong> attractions and their qualityrat<strong>in</strong>gs across the 50 <strong>North</strong> American cities. Global Insight selected these publicationsbased on their extensive and consistent coverage <strong>of</strong> major metropolitan areas across<strong>North</strong> America and their high on-l<strong>in</strong>e sales rank<strong>in</strong>g. Global Insight believes that these areconsistently the most <strong>in</strong>fluential publications for the 50 cities under study.Michel<strong>in</strong>The Michel<strong>in</strong> travel publication was our ma<strong>in</strong> source <strong>of</strong> attractions and quality rat<strong>in</strong>gs.Michel<strong>in</strong> provided the overall rat<strong>in</strong>g for each city and consistently provided three-star,two-, and one-star quality rat<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> attractions. Global Insight assigned a 0-rat<strong>in</strong>g to theattractions that were not rated.8 The results <strong>of</strong> the survey were provided by the Orlando / Orange County Convention & Visitors Bureau.14

Table 9: Michel<strong>in</strong>’s Rat<strong>in</strong>gsRat<strong>in</strong>g SymbolText3-star *** Highly recommended / Worth a journey2-star ** Recommended / Worth a detour1-star * Interest<strong>in</strong>g / Interest<strong>in</strong>gSource: Michel<strong>in</strong>, 2003.Michel<strong>in</strong> conta<strong>in</strong>ed a comprehensive list <strong>of</strong> accommodations and restaurants andprovided a rat<strong>in</strong>g for these attractions.Frommer'sTable 10: Michel<strong>in</strong>’s Rat<strong>in</strong>gs for Accommodations and RestaurantsHotels Prices Hotel Rat<strong>in</strong>g Restaurants Prices Restaurant Rat<strong>in</strong>g$$$$$ over $300 3 $$$$ over $50 3$$$$ $200-$300 2 $$$ $35-$50 2$$$ $125-$200 1 $$ $20-$35 1$$ $75-$125 1 $ under $20 0$ under $75 0Source: Michel<strong>in</strong>, 2003.Frommer's was a secondary source and was used to complement Michel<strong>in</strong>'s travel guide.Frommer's conta<strong>in</strong>ed a comprehensive list <strong>of</strong> sport events, festivals, and theatre, ballet,and opera performances available <strong>in</strong> each city.Fodor’sFodor’s was used to complement the attractions data obta<strong>in</strong>ed from Michel<strong>in</strong> andFrommer's. Fodor’s conta<strong>in</strong>ed a comprehensive list <strong>of</strong> accommodations and restaurantsand ranked these attractions <strong>in</strong> a manner consistent with Michel<strong>in</strong>.Table 11: Fodor’s Rat<strong>in</strong>gs for Accommodations and RestaurantsHotels Prices Hotel Rat<strong>in</strong>g Restaurants Prices Restaurant Rat<strong>in</strong>g$$$$ over $250 3 $$$$ over $32 3, 2$$$ $170-$250 2 $$$ $22-$32 1$$ $90-$170 1 $$ $13-$21 0$ under $90 0 $ under $13 0Source: Fodor’s, 2002.G. Measures <strong>of</strong> Attraction CountThree types <strong>of</strong> attraction count were used to identify the types <strong>of</strong> attractions that wereimportant <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g tourist visitations 9 . This approach was taken because our analysiscentred on the <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> attractions (and some non-attraction type variables) <strong>in</strong>determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g city visitations. Because this project chose not to focus on economic or other<strong>in</strong>fluences <strong>of</strong> travel, Global Insight did not expect to develop an optimum model to9 To some extent, Global Insight used Richard Florida's approach to develop these three types <strong>of</strong> attractioncount.15

expla<strong>in</strong> city visitations. Consequently, Global Insight focused on a series <strong>of</strong> models thatemploy several attraction count methodologies. It was gratify<strong>in</strong>g that all three measures<strong>of</strong> attraction count yielded generally consistent results.Number <strong>of</strong> AttractionsThe first type <strong>of</strong> attraction count was a simple measure <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> attractions:Visitors city = F (# <strong>of</strong> Attractions city ) (1)This specification postulates a direct relationship between attractions and the number <strong>of</strong>visits. As the number <strong>of</strong> tourist attractions <strong>in</strong>creases, the number <strong>of</strong> visits will also<strong>in</strong>crease. This formula was used to estimate an <strong>in</strong>dividual relationship between touristvisits and each attraction category, sub-category, and types <strong>of</strong> attractions us<strong>in</strong>g theattractions matrix.Normalized AttractionsThe second type <strong>of</strong> attraction count normalized the attraction count by city population <strong>in</strong>order to reduce the <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>of</strong> a city’s size or population <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g visitor counts:Visitors city = F (# <strong>of</strong> Attractions city / Population city ) (2)The count <strong>of</strong> attractions is <strong>of</strong>ten affected by the population size <strong>of</strong> the MSA or CMA. Forexample, the total count <strong>of</strong> attractions <strong>in</strong> New York is close to 300 and the populationbase is about 9.5 million, while the attractions count <strong>in</strong> Edmonton is 60 with thepopulation size close to 1 million.To correct for the population bias, the first equation was normalized by the populationsize. In the new equation, there is a direct relationship between the attractions count percapita and the number <strong>of</strong> visits. Therefore, as the number <strong>of</strong> attractions per capita<strong>in</strong>creases, the number <strong>of</strong> visits will also <strong>in</strong>crease.Normalized Share <strong>of</strong> AttractionsThe third type <strong>of</strong> attraction count measures shares <strong>of</strong> both visitors and normalizedattractions:Visitors city / Visitors NA = F ( # <strong>of</strong> Attractions city / # <strong>of</strong> Attractions NA ) (3)(Population city / Population NA )This formula is a location quotient that measures the percentage <strong>of</strong> a total attraction count<strong>in</strong> a particular city compared to the <strong>North</strong> American (NA) total count <strong>of</strong> attractionsdivided by the percentage <strong>of</strong> total population <strong>in</strong> this city compared to the total <strong>North</strong>American population. It is important to note that the left-hand side <strong>of</strong> this equation isslightly different from two previous notations. This time the left-hand side measures thenumber <strong>of</strong> visits to a particular city compared to the total number <strong>of</strong> visits to <strong>North</strong>America.This measure is a ratio. If the value <strong>of</strong> this ratio is greater than one, this shows that aparticular city has a greater share <strong>of</strong> attractions than the <strong>North</strong> American average, while a16

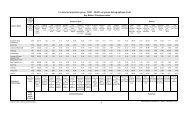

value below one suggests that the share <strong>of</strong> attractions for this city is below the <strong>North</strong>American average.H. Discussion <strong>of</strong> ResultsThe analysis proceeded <strong>in</strong> three steps to arrive to the set <strong>of</strong> five econometric models thatyielded robust results 10 . The structure <strong>of</strong> these models allowed Global Insight to identifyand rank the relative return <strong>of</strong>fered by each type <strong>of</strong> attraction <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong>visitations it can generate. Based on these models, Global Insight can identify a subset <strong>of</strong>the most important attraction types for generat<strong>in</strong>g city visits. Furthermore, Global Insightcan recommend an effective attractions development and promotional tourism strategyfor Toronto and Ottawa to enhance future visitations. It is important to emphasize that allfive models were robust and conta<strong>in</strong>ed unique characteristicsKey F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsStep 1: For this step, Global Insight used all three measures <strong>of</strong> attraction count. Leisurevisitations were regressed aga<strong>in</strong>st each <strong>of</strong> these measures <strong>of</strong> attraction count (i.e. number<strong>of</strong> attractions, normalized attractions, and normalized share <strong>of</strong> attractions) for each type<strong>of</strong> attraction, attraction category, and sub-category accord<strong>in</strong>g to the structure <strong>of</strong> theattractions matrix. Global Insight modelled total count <strong>of</strong> attractions and quality-ratedattractions (i.e. Q3, Q2, and Q1) separately. Table 12 summarizes our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. In thistable, areas highlighted with dark colour represent statistically significant results with t-statistics above 2, while areas highlighted with light colour show marg<strong>in</strong>ally significantresults with t-statistics between 1 and 2 11 . Please note that the quality count <strong>of</strong> cas<strong>in</strong>os,opera, and theatre performances was not available. Conversely, the follow<strong>in</strong>g tablesummarizes the types <strong>of</strong> attractions, attraction categories, and sub-categories that did notwork for all three types <strong>of</strong> attraction measures.Note that there is a consistent statistical significance among all three attraction countmeasures for physical sett<strong>in</strong>g, urban amenities, built form, and popular enterta<strong>in</strong>ment. Inthis step, these categories and their related subcategories seemed to be the most highlycorrelated with leisure visitation, regardless <strong>of</strong> the attraction count measure used.10 These results were robust <strong>in</strong> terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual t-statistics for different types <strong>of</strong> tourist attractions andadjusted R 2 .11 t-statistics refer to a statistical “goodness-<strong>of</strong>-fit” measure that <strong>in</strong>dicated the likelihood that the coefficientestimated for the explanatory variable is, <strong>in</strong> fact, greater than 0. Thus, very low t-statistics suggest that thereis no mean<strong>in</strong>gful causation implied between the explanatory variable (the attractions variable) and the<strong>in</strong>dependent variable (the number <strong>of</strong> visitations). t-statistics greater than 2.0 are generally regarded ashighly significant.17

Table 12: Modell<strong>in</strong>g Tourist Visitations on Individual Attractions – SignificantResultsType <strong>of</strong> AttractionCount Normalized Count Normalized ShareTC Q3 Q2 Q1 TC Q3 Q2 Q1 TC Q3 Q2 Q1Arts&CultureMuseumsGeneral History MuseumsHistoric SitesOther Themed MuseumsVisual ArtsArt GalleriesEnvironment and Built FormPhysical Sett<strong>in</strong>gWaterfronts & Beaches<strong>Urban</strong> AmenitiesParks and Green SpacesShopp<strong>in</strong>g AreasBus<strong>in</strong>ess DistrictsBuilt FormGeneral Build<strong>in</strong>g ArchitectureSpecific Structures <strong>of</strong> InterestEnterta<strong>in</strong>mentPopular Enterta<strong>in</strong>mentAmusement and Theme ParksCas<strong>in</strong>os X X X X X X X X XCultural Enterta<strong>in</strong>mentOpera X X X X X X X X XTheatre X X X X X X X X XAccommodation and FoodAccommodationLuxury Hotel RoomsFoodHigh-End RestaurantsSource: Global Insight, Inc.Conversely, the attraction categories shown <strong>in</strong> Table 13 generally did not exhibit aconsistent statistical significance <strong>in</strong> their correlation with attractions.18

Table 13: Individual Attractions That Did Not WorkArts & CultureVisual ArtsArts Related Events and FestivalsEnvironment and Built FormPhysical Sett<strong>in</strong>gGeographic FeaturesAccommodation and FoodFoodFood Related Events and FestivalsRange <strong>of</strong> RestaurantsEnterta<strong>in</strong>mentPopular Enterta<strong>in</strong>mentSpectator Sports OpportunitiesPopular Events or FestivalsNight ClubsCultural Enterta<strong>in</strong>mentBallet PASymphony Orchestra PASource: Global Insight, Inc.Step 2: From Step 1, the attractions with positive, statistically significant coefficients andrelatively high adjusted R-squared were sequentially comb<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>to a regression witheach <strong>of</strong> the other attractions. Global Insight found that this significantly <strong>in</strong>creased thevalues <strong>of</strong> the adjusted R 2 . Table 14 summarizes the equations with two types <strong>of</strong>attractions that yielded relatively high adjusted R 2 12 . Comb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g two types <strong>of</strong> attractionssignificantly improved the adjusted R 2 . Please note that at this stage, Global Insightdecided to proceed with only one measure <strong>of</strong> attraction count–Number <strong>of</strong> Attractions.When the total count <strong>of</strong> attractions was used, a wide variety <strong>of</strong> attractions turned out to besignificant. The other two measures <strong>of</strong> attraction count confirmed our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs but limitedthe range <strong>of</strong> attractions. S<strong>in</strong>ce Global Insight wanted to ascerta<strong>in</strong> the most complete list<strong>of</strong> attractions possible, only total count <strong>of</strong> attractions was selected for further analysis.Table 14: Comb<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Two Types <strong>of</strong> Attractions–Significant Results 13Type <strong>of</strong> AttractionType <strong>of</strong> Second AttractionAdj.R 2Cas<strong>in</strong>os (TC)Shopp<strong>in</strong>g Areas (TC)0.14Specific Structures (TC)Amusement Parks (TC)0.15Cas<strong>in</strong>os (TC)Built Form (TC)0.15Cas<strong>in</strong>os (TC)Specific Structures (TC)0.20Popular Enterta<strong>in</strong>ment (Q1)Waterfronts & Beaches (Q1)0.33Popular Enterta<strong>in</strong>ment (Q1)Amusement Parks (Q3)Shopp<strong>in</strong>g Areas (Q1)<strong>Urban</strong> Amenities (Q3)0.390.50Amusement Parks (Q3)Amusement Parks (Q3)Visual Art Galleries (Q3)Shopp<strong>in</strong>g Areas (Q3)0.520.52Source: Global Insight, Inc.12 The adjusted R 2 statistic <strong>in</strong>dicates the degree to which the variation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dependent variable(visitations) from its mean is expla<strong>in</strong>ed by the dependent variables used <strong>in</strong> the regression. An adjusted R 2value <strong>of</strong> 0.9 <strong>in</strong>dicates that 90% <strong>of</strong> the variation is expla<strong>in</strong>ed.13 Q3 = three-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, Q2 = two-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, Q1 = one-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, and TC = total count.19

Step 3: In Step 3, more attraction variables were tried <strong>in</strong> the equations summarized <strong>in</strong>Table 14. In addition, non-attraction variables were also exam<strong>in</strong>ed to see whether byadd<strong>in</strong>g them <strong>in</strong> these regressions the adjusted R 2 was improved.Table 15: Non-Attraction VariablesType <strong>of</strong> VariableOverall City Score (from Michel<strong>in</strong>)Population by State or Prov<strong>in</strong>ceHotel Room CountProperty CountPublic Transportation ScoreFilter Variable for International AirportFilter Variable for a Large Hub AirportTotal Count <strong>of</strong> Miss<strong>in</strong>g AttractionsPopulation DensityProximity to Major Metro AreasCity-by-city Market<strong>in</strong>g BudgetsSignificanceNoYesYesYesYesNoNoNoYesNoYesSource: Global Insight, Inc.Hav<strong>in</strong>g completed these three steps, the follow<strong>in</strong>g comb<strong>in</strong>ations <strong>of</strong> attraction and nonattractionvariables emerged. Table 16 presents five equations that proved to be the mostpromis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the variation <strong>of</strong> leisure visitors among the 50 <strong>North</strong> Americancities.20

Table 16: Significant Results 14Equation Type <strong>of</strong> Attraction Type <strong>of</strong> SecondAttractionAttraction and Non-Attraction VariablesAdj. R 2(1) PopularEnterta<strong>in</strong>ment (Q1)Shopp<strong>in</strong>gAreas(Q1)Room Count 0.69(2) PopularEnterta<strong>in</strong>ment (Q2)- Room Count 0.70(3) Amusement Parks(Q3)Specific Structures(Q3)Cas<strong>in</strong>os (TC),Shopp<strong>in</strong>g Areas (Q3)& Properties Count0.76(3B)Amusement Parks(Q3)Specific Structures(Q3)Cas<strong>in</strong>os (TC),Shopp<strong>in</strong>g Areas (Q3),Properties Count &Pop. Density0.84(4) Amusement Parks(Q3)Specific Structures(Q3)Cas<strong>in</strong>os (TC), PublicTransportation Score& Pop. Density0.78(5) Amusement Parks(Q3)Specific Structures(Q3)Shopp<strong>in</strong>g Areas (Q3)& Room Count0.88(5B)Amusement Parks(Q3)Specific Structures(Q3)Shopp<strong>in</strong>g Areas (Q3),Room Count & Pop.Density0.90(5C)Amusement Parks(Q3)Specific Structures(Q3)Shopp<strong>in</strong>g Areas (Q3),Room Count &Market<strong>in</strong>g Budgets0.90Source: Global Insight, Inc.I. Interpretation <strong>of</strong> Regression ResultsResults from our analysis support many <strong>of</strong> the common themes found <strong>in</strong> the literaturereview. Empirically, Global Insight was able to confirm the follow<strong>in</strong>g propositions fromthe literature review.• Tourists are look<strong>in</strong>g for a “quality” experience, not merely to visit a site.• Comb<strong>in</strong>ations <strong>of</strong> quality-rated attractions expla<strong>in</strong> more variation <strong>in</strong> visits thantotal count <strong>of</strong> these types <strong>of</strong> attractions.• Cluster<strong>in</strong>g plays an important role. Interaction <strong>of</strong> multiple sites at the dest<strong>in</strong>ationis crucial.• Comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> quality-rated attractions produces higher adjusted R 2 than thesetypes <strong>of</strong> attractions taken <strong>in</strong>dividually.• Infrastructure is important. Sufficient tourist <strong>in</strong>frastructure is necessary tomaximize tourists’ participation <strong>in</strong> and enjoyment <strong>of</strong> the dest<strong>in</strong>ation.• Hotel room and property count were statistically significant.14 Q3 = three-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, Q2 = two-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, Q1 = one-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, and TC = total count.21

• Public transportation score obta<strong>in</strong>ed from “Places Rated Almanac” publicationwas marg<strong>in</strong>ally significant.• <strong>Urban</strong> Tourism Market<strong>in</strong>g plays an important role <strong>in</strong> attract<strong>in</strong>g more tourists.Tourism market<strong>in</strong>g contributes to the <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> visits across 33 cities <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong>the sample.• Tourists want to be enterta<strong>in</strong>ed. For example, the comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> cas<strong>in</strong>os withamusement parks and specific structures (i.e. Statue <strong>of</strong> Liberty or CN Tower)supports the argument that tourist wants to be enterta<strong>in</strong>ed.• Quality shopp<strong>in</strong>g is an important part <strong>of</strong> the tourism experience. Quality-ratedshopp<strong>in</strong>g areas expla<strong>in</strong> more variation <strong>in</strong> visits than total count <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong>attractions.Regression-Specific ConclusionsIn this section, Global Insight addresses the regression-specific results for fiveeconometric models.Model 1: In Model 1, the number <strong>of</strong> visits was regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> popularenterta<strong>in</strong>ment types <strong>of</strong> attractions with the one-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, the number <strong>of</strong> shopp<strong>in</strong>g areaswith the one-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, and the number <strong>of</strong> hotel rooms. The adjusted R 2 for this model is69%. For more details about this model see Technical Appendix Section B. The ma<strong>in</strong>conclusions <strong>of</strong> this model are as follows:• On average across all cities, by build<strong>in</strong>g a one-star attraction from a popularenterta<strong>in</strong>ment category, the number <strong>of</strong> visitors will <strong>in</strong>crease by 600,000.• On average across all cities, by build<strong>in</strong>g a one-star shopp<strong>in</strong>g area, the number <strong>of</strong>visitors will <strong>in</strong>crease by 1.15 million.• On average across all cities, by <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the number <strong>of</strong> hotel rooms by 100, thenumber <strong>of</strong> visitors will <strong>in</strong>crease by 10,000.• Comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> one-star attractions from the popular enterta<strong>in</strong>ment category withone-star shopp<strong>in</strong>g areas supports the argument that tourists want to beenterta<strong>in</strong>ed.• Quality-rated shopp<strong>in</strong>g areas and attractions from the popular enterta<strong>in</strong>mentcategory expla<strong>in</strong> more variation <strong>in</strong> visits than total count <strong>of</strong> these types <strong>of</strong>attractions.• Cluster<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> attractions is important. Comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> quality-rated shopp<strong>in</strong>gareas and attractions from the popular enterta<strong>in</strong>ment category produces higheradjusted R 2 than these types <strong>of</strong> attractions taken <strong>in</strong>dividually.• Infrastructure is important <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g tourist visitations s<strong>in</strong>ce hotel roomcount was statistically significant.Model 2: In Model 2, the number <strong>of</strong> visits was regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> popularenterta<strong>in</strong>ment types <strong>of</strong> attractions with the two-star rat<strong>in</strong>g and the number <strong>of</strong> hotel rooms.22

The adjusted R 2 for this model is 70%. For more details about this model see TechnicalAppendix Section B. The ma<strong>in</strong> conclusions <strong>of</strong> this model are as follows:• On average across all cities, by build<strong>in</strong>g one, two-star attraction from a popularenterta<strong>in</strong>ment category <strong>of</strong> attractions, the number <strong>of</strong> visitors will <strong>in</strong>crease by520,000.• On average across all cities, by <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the number <strong>of</strong> hotel rooms by 100, thenumber <strong>of</strong> visitors will <strong>in</strong>crease by 10,000.• Statistical significance <strong>of</strong> two-star attractions from the popular enterta<strong>in</strong>mentcategory <strong>of</strong> tourist attractions supports the argument that tourists want to beenterta<strong>in</strong>ed.• Quality-rated attractions from the popular enterta<strong>in</strong>ment category <strong>of</strong> touristattractions expla<strong>in</strong> more variation <strong>in</strong> visits than total count <strong>of</strong> attractions <strong>in</strong> thiscategory.• Infrastructure is important <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g tourist visitations s<strong>in</strong>ce hotel roomcount was statistically significant.Model 3: In Model 3, the number <strong>of</strong> visits was regressed on the number <strong>of</strong> amusementparks with the three-star rat<strong>in</strong>g, the number <strong>of</strong> specific structures with the three-starrat<strong>in</strong>g, the total count <strong>of</strong> cas<strong>in</strong>os, the number <strong>of</strong> shopp<strong>in</strong>g areas with the three-star rat<strong>in</strong>gand the number <strong>of</strong> properties. The adjusted R 2 for this model is 76%. For more detailsabout this model see Technical Appendix Section B. The ma<strong>in</strong> conclusions <strong>of</strong> this modelare as follows:• On average across all cities, by build<strong>in</strong>g one three-star specific structure, thenumber <strong>of</strong> visitors will <strong>in</strong>crease by 1.95 million.• On average across all cities, by build<strong>in</strong>g one three-star amusement park, thenumber <strong>of</strong> visitors will <strong>in</strong>crease by 6.67 million.• On average across all cities, by build<strong>in</strong>g one cas<strong>in</strong>o, the number <strong>of</strong> visitors will<strong>in</strong>crease by 430,000.• On average across all cities, by build<strong>in</strong>g one three-star shopp<strong>in</strong>g area, the number<strong>of</strong> visitors will <strong>in</strong>crease by 810,000.• On average across all cities, by build<strong>in</strong>g one hotel, the number <strong>of</strong> visitors will<strong>in</strong>crease by 7,000.• Comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> cas<strong>in</strong>os with amusement parks, specific structures (i.e. Statue <strong>of</strong>Liberty or CN Tower) and shopp<strong>in</strong>g areas supports the argument that touristswant to be enterta<strong>in</strong>ed.• Quality-rated amusement parks, specific structures and shopp<strong>in</strong>g areas expla<strong>in</strong>more variation <strong>in</strong> visits than total count <strong>of</strong> these types <strong>of</strong> attractions.• Cluster<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> attractions is important. Comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> cas<strong>in</strong>os with amusementparks, specific structures, and shopp<strong>in</strong>g areas produces higher adjusted R 2 thanthese types <strong>of</strong> attractions taken <strong>in</strong>dividually.23