Feeding hunger and insecurity

Feeding hunger and insecurity

Feeding hunger and insecurity

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

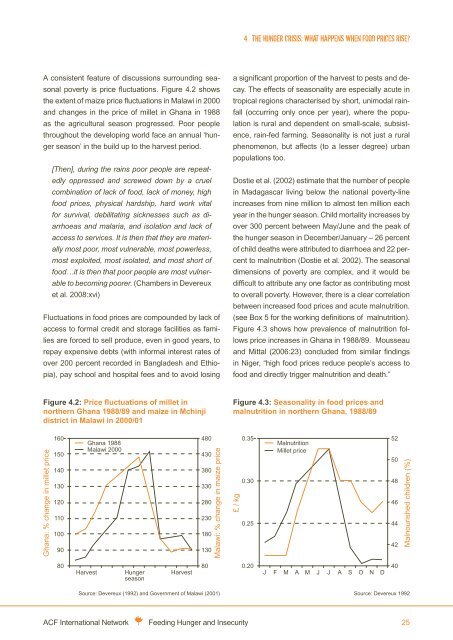

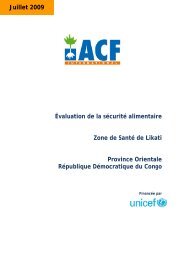

4. the <strong>hunger</strong> crisis: what happens when food prices rise?A consistent feature of discussions surrounding seasonalpoverty is price fluctuations. Figure 4.2 showsthe extent of maize price fluctuations in Malawi in 2000<strong>and</strong> changes in the price of millet in Ghana in 1988as the agricultural season progressed. Poor peoplethroughout the developing world face an annual ‘<strong>hunger</strong>season’ in the build up to the harvest period.[Then], during the rains poor people are repeatedlyoppressed <strong>and</strong> screwed down by a cruelcombination of lack of food, lack of money, highfood prices, physical hardship, hard work vitalfor survival, debilitating sicknesses such as diarrhoeas<strong>and</strong> malaria, <strong>and</strong> isolation <strong>and</strong> lack ofaccess to services. It is then that they are materiallymost poor, most vulnerable, most powerless,most exploited, most isolated, <strong>and</strong> most short offood…it is then that poor people are most vulnerableto becoming poorer. (Chambers in Devereuxet al. 2008:xvi)Fluctuations in food prices are compounded by lack ofaccess to formal credit <strong>and</strong> storage facilities as familiesare forced to sell produce, even in good years, torepay expensive debts (with informal interest rates ofover 200 percent recorded in Bangladesh <strong>and</strong> Ethiopia),pay school <strong>and</strong> hospital fees <strong>and</strong> to avoid losinga significant proportion of the harvest to pests <strong>and</strong> decay.The effects of seasonality are especially acute intropical regions characterised by short, unimodal rainfall(occurring only once per year), where the populationis rural <strong>and</strong> dependent on small-scale, subsistence,rain-fed farming. Seasonality is not just a ruralphenomenon, but affects (to a lesser degree) urbanpopulations too.Dostie et al. (2002) estimate that the number of peoplein Madagascar living below the national poverty-lineincreases from nine million to almost ten million eachyear in the <strong>hunger</strong> season. Child mortality increases byover 300 percent between May/June <strong>and</strong> the peak ofthe <strong>hunger</strong> season in December/January – 26 percentof child deaths were attributed to diarrhoea <strong>and</strong> 22 percentto malnutrition (Dostie et al. 2002). The seasonaldimensions of poverty are complex, <strong>and</strong> it would bedifficult to attribute any one factor as contributing mostto overall poverty. However, there is a clear correlationbetween increased food prices <strong>and</strong> acute malnutrition.(see Box 5 for the working definitions of malnutrition).Figure 4.3 shows how prevalence of malnutrition followsprice increases in Ghana in 1988/89. Mousseau<strong>and</strong> Mittal (2006:23) concluded from similar findingsin Niger, “high food prices reduce people’s access tofood <strong>and</strong> directly trigger malnutrition <strong>and</strong> death.”Figure 4.2: Price fluctuations of millet innorthern Ghana 1988/89 <strong>and</strong> maize in Mchinjidistrict in Malawi in 2000/01Figure 4.3: Seasonality in food prices <strong>and</strong>malnutrition in northern Ghana, 1988/89Ghana: % change in millet price16015014013012011010090Ghana 1988Malawi 2000480430380330280230180130Malawi: % change in maize price£ / kg0.350.300.25MalnutritionMillet price525048464442Malnourished children (%)80HarvestHungerseasonHarvest800.20JFM A M J J A S O N D40Source: Devereux (1992) <strong>and</strong> Government of Malawi (2001)Source: Devereux 1992ACF International Network <strong>Feeding</strong> Hunger <strong>and</strong> Insecurity 25