Feeding hunger and insecurity

Feeding hunger and insecurity

Feeding hunger and insecurity

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

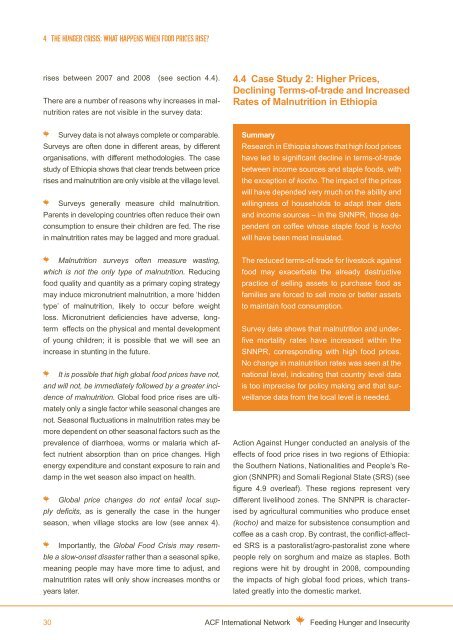

4. the <strong>hunger</strong> crisis: what happens when food prices rise?rises between 2007 <strong>and</strong> 2008 (see section 4.4).There are a number of reasons why increases in malnutritionrates are not visible in the survey data:4.4 Case Study 2: Higher Prices,Declining Terms-of-trade <strong>and</strong> IncreasedRates of Malnutrition in EthiopiaSurvey data is not always complete or comparable.Surveys are often done in different areas, by differentorganisations, with different methodologies. The casestudy of Ethiopia shows that clear trends between pricerises <strong>and</strong> malnutrition are only visible at the village level.Surveys generally measure child malnutrition.Parents in developing countries often reduce their ownconsumption to ensure their children are fed. The risein malnutrition rates may be lagged <strong>and</strong> more gradual.SummaryResearch in Ethiopia shows that high food priceshave led to significant decline in terms-of-tradebetween income sources <strong>and</strong> staple foods, withthe exception of kocho. The impact of the priceswill have depended very much on the ability <strong>and</strong>willingness of households to adapt their diets<strong>and</strong> income sources – in the SNNPR, those dependenton coffee whose staple food is kochowill have been most insulated.Malnutrition surveys often measure wasting,which is not the only type of malnutrition. Reducingfood quality <strong>and</strong> quantity as a primary coping strategymay induce micronutrient malnutrition, a more ‘hiddentype’ of malnutrition, likely to occur before weightloss. Micronutrient deficiencies have adverse, longtermeffects on the physical <strong>and</strong> mental developmentof young children; it is possible that we will see anincrease in stunting in the future.It is possible that high global food prices have not,<strong>and</strong> will not, be immediately followed by a greater incidenceof malnutrition. Global food price rises are ultimatelyonly a single factor while seasonal changes arenot. Seasonal fluctuations in malnutrition rates may bemore dependent on other seasonal factors such as theprevalence of diarrhoea, worms or malaria which affectnutrient absorption than on price changes. Highenergy expenditure <strong>and</strong> constant exposure to rain <strong>and</strong>damp in the wet season also impact on health.Global price changes do not entail local supplydeficits, as is generally the case in the <strong>hunger</strong>season, when village stocks are low (see annex 4).Importantly, the Global Food Crisis may resemblea slow-onset disaster rather than a seasonal spike,meaning people may have more time to adjust, <strong>and</strong>malnutrition rates will only show increases months oryears later.The reduced terms-of-trade for livestock againstfood may exacerbate the already destructivepractice of selling assets to purchase food asfamilies are forced to sell more or better assetsto maintain food consumption.Survey data shows that malnutrition <strong>and</strong> underfivemortality rates have increased within theSNNPR, corresponding with high food prices.No change in malnutrition rates was seen at thenational level, indicating that country level datais too imprecise for policy making <strong>and</strong> that surveillancedata from the local level is needed.Action Against Hunger conducted an analysis of theeffects of food price rises in two regions of Ethiopia:the Southern Nations, Nationalities <strong>and</strong> People’s Region(SNNPR) <strong>and</strong> Somali Regional State (SRS) (seefigure 4.9 overleaf). These regions represent verydifferent livelihood zones. The SNNPR is characterisedby agricultural communities who produce enset(kocho) <strong>and</strong> maize for subsistence consumption <strong>and</strong>coffee as a cash crop. By contrast, the conflict-affectedSRS is a pastoralist/agro-pastoralist zone wherepeople rely on sorghum <strong>and</strong> maize as staples. Bothregions were hit by drought in 2008, compoundingthe impacts of high global food prices, which translatedgreatly into the domestic market.30ACF International Network<strong>Feeding</strong> Hunger <strong>and</strong> Insecurity