Feeding hunger and insecurity

Feeding hunger and insecurity

Feeding hunger and insecurity

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

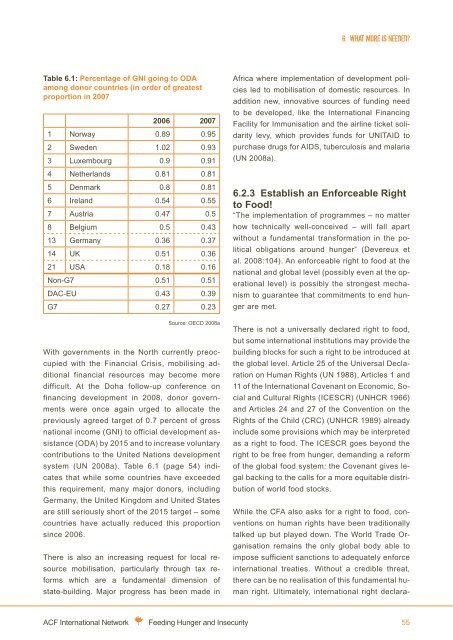

6. what more is needed?Table 6.1: Percentage of GNI going to ODAamong donor countries (in order of greatestproportion in 20072006 20071 Norway 0.89 0.952 Sweden 1.02 0.933 Luxembourg 0.9 0.914 Netherl<strong>and</strong>s 0.81 0.815 Denmark 0.8 0.816 Irel<strong>and</strong> 0.54 0.557 Austria 0.47 0.58 Belgium 0.5 0.4313 Germany 0.36 0.3714 UK 0.51 0.3621 USA 0.18 0.16Non-G7 0.51 0.51DAC-EU 0.43 0.39G7 0.27 0.23Source: OECD 2008aWith governments in the North currently preoccupiedwith the Financial Crisis, mobilising additionalfinancial resources may become moredifficult. At the Doha follow-up conference onfinancing development in 2008, donor governmentswere once again urged to allocate thepreviously agreed target of 0.7 percent of grossnational income (GNI) to official development assistance(ODA) by 2015 <strong>and</strong> to increase voluntarycontributions to the United Nations developmentsystem (UN 2008a). Table 6.1 (page 54) indicatesthat while some countries have exceededthis requirement, many major donors, includingGermany, the United Kingdom <strong>and</strong> United Statesare still seriously short of the 2015 target – somecountries have actually reduced this proportionsince 2006.There is also an increasing request for local resourcemobilisation, particularly through tax reformswhich are a fundamental dimension ofstate-building. Major progress has been made inAfrica where implementation of development policiesled to mobilisation of domestic resources. Inaddition new, innovative sources of funding needto be developed, like the International FinancingFacility for Immunisation <strong>and</strong> the airline ticket solidaritylevy, which provides funds for UNITAID topurchase drugs for AIDS, tuberculosis <strong>and</strong> malaria(UN 2008a).6.2.3 Establish an Enforceable Rightto Food!“The implementation of programmes – no matterhow technically well-conceived – will fall apartwithout a fundamental transformation in the politicalobligations around <strong>hunger</strong>” (Devereux etal. 2008:104). An enforceable right to food at thenational <strong>and</strong> global level (possibly even at the operationallevel) is possibly the strongest mechanismto guarantee that commitments to end <strong>hunger</strong>are met.There is not a universally declared right to food,but some international institutions may provide thebuilding blocks for such a right to be introduced atthe global level. Article 25 of the Universal Declarationon Human Rights (UN 1988), Articles 1 <strong>and</strong>11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social<strong>and</strong> Cultural Rights (ICESCR) (UNHCR 1966)<strong>and</strong> Articles 24 <strong>and</strong> 27 of the Convention on theRights of the Child (CRC) (UNHCR 1989) alreadyinclude some provisions which may be interpretedas a right to food. The ICESCR goes beyond theright to be free from <strong>hunger</strong>, dem<strong>and</strong>ing a reformof the global food system; the Covenant gives legalbacking to the calls for a more equitable distributionof world food stocks.While the CFA also asks for a right to food, conventionson human rights have been traditionallytalked up but played down. The World Trade Organisationremains the only global body able toimpose sufficient sanctions to adequately enforceinternational treaties. Without a credible threat,there can be no realisation of this fundamental humanright. Ultimately, international right declara-ACF International Network <strong>Feeding</strong> Hunger <strong>and</strong> Insecurity 55