ISSUE 125 : Jul/Aug - 1997 - Australian Defence Force Journal

ISSUE 125 : Jul/Aug - 1997 - Australian Defence Force Journal

ISSUE 125 : Jul/Aug - 1997 - Australian Defence Force Journal

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

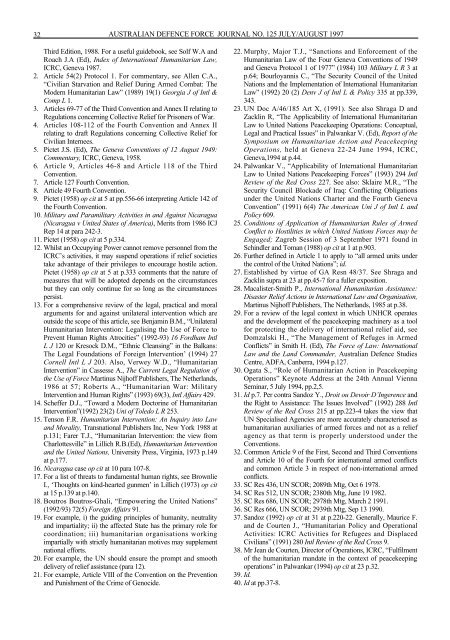

32AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE JOURNAL NO. <strong>125</strong> JULY/AUGUST <strong>1997</strong>Third Edition, 1988. For a useful guidebook, see Solf W.A andRoach J.A (Ed), Index of International Humanitarian Law,ICRC, Geneva 1987.2. Article 54(2) Protocol 1. For commentary, see Allen C.A.,“Civilian Starvation and Relief During Armed Combat: TheModern Humanitarian Law” (1989) 19(1) Georgia J of Intl &Comp L 1.3. Articles 69-77 of the Third Convention and Annex II relating toRegulations concerning Collective Relief for Prisoners of War.4. Articles 108-112 of the Fourth Convention and Annex IIrelating to draft Regulations concerning Collective Relief forCivilian Internees.5. Pictet J.S. (Ed), The Geneva Conventions of 12 <strong>Aug</strong>ust 1949:Commentary, ICRC, Geneva, 1958.6. Article 9, Articles 46-8 and Article 118 of the ThirdConvention.7. Article 127 Fourth Convention.8. Article 49 Fourth Convention.9. Pictet (1958) op cit at 5 at pp.556-66 interpreting Article 142 ofthe Fourth Convention.10. Military and Paramilitary Activities in and Against Nicaragua(Nicaragua v United States of America), Merits from 1986 ICJRep 14 at para 242-3.11. Pictet (1958) op cit at 5 p.334.12. Whilst an Occupying Power cannot remove personnel from theICRC’s activities, it may suspend operations if relief societiestake advantage of their privileges to encourage hostile action.Pictet (1958) op cit at 5 at p.333 comments that the nature ofmeasures that will be adopted depends on the circumstancesbut they can only continue for so long as the circumstancespersist.13. For a comprehensive review of the legal, practical and moralarguments for and against unilateral intervention which areoutside the scope of this article, see Benjamin B.M., “UnilateralHumanitarian Intervention: Legalising the Use of <strong>Force</strong> toPrevent Human Rights Atrocities” (1992-93) 16 Fordham IntlL J 120 or Kresock D.M., “Ethnic Cleansing” in the Balkans:The Legal Foundations of Foreign Intervention’ (1994) 27Cornell Intl L J 203. Also, Verwey W.D., “HumanitarianIntervention” in Cassesse A., The Current Legal Regulation ofthe Use of <strong>Force</strong> Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, The Netherlands,1986 at 57; Roberts A., “Humanitarian War: MilitaryIntervention and Human Rights” (1993) 69(3), Intl Affairs 429.14. Scheffer D.J., “Toward a Modern Doctorine of HumanitarianIntervention”(1992) 23(2) Uni of Toledo L R 253.15. Tenson F.R. Humanitarian Intervention: An Inquiry into Lawand Morality, Transnational Publishers Inc, New York 1988 atp.131; Farer T.J., “Humanitarian Intervention: the view fromCharlottesville” in Lillich R.B.(Ed), Humanitarian Interventionand the United Nations, University Press, Virginia, 1973 p.149at p.177.16. Nicaragua case op cit at 10 para 107-8.17. For a list of threats to fundamental human rights, see BrownlieI., ‘Thoughts on kind-hearted gunmen’ in Lillich (1973) op citat 15 p.139 at p.140.18. Boutros Boutros-Ghali, “Empowering the United Nations”(1992/93) 72(5) Foreign Affairs 91.19. For example, i) the guiding principles of humanity, neutralityand impartiality; ii) the affected State has the primary role forcoordination; iii) humanitarian organisations workingimpartially with strictly humanitarian motives may supplementnational efforts.20. For example, the UN should ensure the prompt and smoothdelivery of relief assistance (para 12).21. For example, Article VIII of the Convention on the Preventionand Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.22. Murphy, Major T.J., “Sanctions and Enforcement of theHumanitarian Law of the Four Geneva Conventions of 1949and Geneva Protocol 1 of 1977” (1984) 103 Military L R 3 atp.64; Bourloyannis C., “The Security Council of the UnitedNations and the Implementation of International HumanitarianLaw” (1992) 20 (2) Denv J of Intl L & Policy 335 at pp.339,343.23. UN Doc A/46/185 Art X, (1991). See also Shraga D andZacklin R, “The Applicability of International HumanitarianLaw to United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Conceptual,Legal and Practical Issues” in Palwankar V. (Ed), Report of theSymposium on Humanitarian Action and PeacekeepingOperations, held at Geneva 22-24 June 1994, ICRC,Geneva,1994 at p.44.24. Palwankar V., “Applicability of International HumanitarianLaw to United Nations Peacekeeping <strong>Force</strong>s” (1993) 294 IntlReview of the Red Cross 227. See also: Sklaire M.R., “TheSecurity Council Blockade of Iraq: Conflicting Obligationsunder the United Nations Charter and the Fourth GenevaConvention” (1991) 6(4) The American Uni J of Intl L andPolicy 609.25. Conditions of Application of Humanitarian Rules of ArmedConflict to Hostilities in which United Nations <strong>Force</strong>s may beEngaged; Zagreb Session of 3 September 1971 found inSchindler and Toman (1988) op cit at 1 at p.903.26. Further defined in Article 1 to apply to “all armed units underthe control of the United Nations”; id.27. Established by virtue of GA Resn 48/37. See Shraga andZacklin supra at 23 at pp.45-7 for a fuller exposition.28. Macalister-Smith P., International Humanitarian Assistance:Disaster Relief Actions in International Law and Organisation,Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, The Netherlands, 1985 at p.38.29. For a review of the legal context in which UNHCR operatesand the development of the peacekeeping machinery as a toolfor protecting the delivery of international relief aid, seeDomzalski H., “The Management of Refuges in ArmedConflicts” in Smith H. (Ed), The <strong>Force</strong> of Law: InternationalLaw and the Land Commander, <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> StudiesCentre, ADFA, Canberra, 1994 p.127.30. Ogata S., “Role of Humanitarian Action in PeacekeepingOperations” Keynote Address at the 24th Annual ViennaSeminar, 5 <strong>Jul</strong>y 1994, pp.2,5.31. Id p.7. Per contra Sandoz Y., Droit ou Devoir D’Ingerence andthe Right to Assistance: The Issues Involved” (1992) 288 IntlReview of the Red Cross 215 at pp.223-4 takes the view thatUN Specialised Agencies are more accurately characterised ashumanitarian auxiliaries of armed forces and not as a reliefagency as that term is properly understood under theConventions.32. Common Article 9 of the First, Second and Third Conventionsand Article 10 of the Fourth for international armed conflictsand common Article 3 in respect of non-international armedconflicts.33. SC Res 436, UN SCOR; 2089th Mtg, Oct 6 1978.34. SC Res 512, UN SCOR; 2380th Mtg, June 19 1982.35. SC Res 686, UN SCOR; 2978th Mtg, March 2 1991.36. SC Res 666, UN SCOR; 2939th Mtg, Sep 13 1990.37. Sandoz (1992) op cit at 31 at p.220-22. Generally, Maurice F.and de Courten J., “Humanitarian Policy and OperationalActivities: ICRC Activities for Refugees and DisplacedCivilians” (1991) 280 Intl Review of the Red Cross 9.38. Mr Jean de Courten, Director of Operations, ICRC, “Fulfilmentof the humanitarian mandate in the context of peacekeepingoperations” in Palwankar (1994) op cit at 23 p.32.39. Id.40. Id at pp.37-8.