Noun, verb and adjective are not categories of ... - grandionline.net

Noun, verb and adjective are not categories of ... - grandionline.net

Noun, verb and adjective are not categories of ... - grandionline.net

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

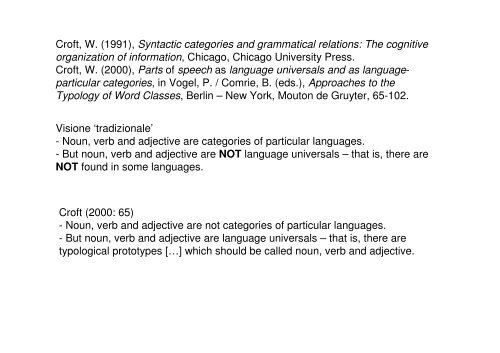

Cr<strong>of</strong>t, W. (1991), Syntactic <strong>categories</strong> <strong>and</strong> grammatical relations: The cognitiveorganization <strong>of</strong> information, Chicago, Chicago University Press.Cr<strong>of</strong>t, W. (2000), Parts <strong>of</strong> speech as language universals <strong>and</strong> as languageparticular<strong>categories</strong>, in Vogel, P. / Comrie, B. (eds.), Approaches to theTypology <strong>of</strong> Word Classes, Berlin – New York, Mouton de Gruyter, 65-102.Visione ‘tradizionale’- <strong>Noun</strong>, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>categories</strong> <strong>of</strong> particular languages.- But noun, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> <strong>are</strong> NOT language universals – that is, there <strong>are</strong>NOT found in some languages.Cr<strong>of</strong>t (2000: 65)- <strong>Noun</strong>, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>not</strong> <strong>categories</strong> <strong>of</strong> particular languages.- But noun, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> <strong>are</strong> language universals – that is, there <strong>are</strong>typological prototypes […] which should be called noun, <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong>.

A proper theory <strong>of</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> speech that applies to all languages must satisfy thefollowing three conditions in order to be successful.First, there must be a criterion for distinguishing parts <strong>of</strong> speech from othermorphosyntactically defined subclasses.Second, there must be a cross-linguistically valid <strong>and</strong> uniform set <strong>of</strong> formalgrammatical criteria for evaluating the universality <strong>of</strong> the parts-<strong>of</strong>-speechdistinctions.Third there must be a clear distinction between language universals <strong>and</strong> particularlanguage facts.

The universal-typological theory <strong>of</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> speech embraces constructions with<strong>and</strong> without function-indicating morphosyntax. Function-indicating morphosyntaxovertly encodes the functions <strong>of</strong> reference, predication <strong>and</strong> modification forvarious classes <strong>of</strong> lexical items. As such, function-indicating morphosyntax fallsunder the structural coding criterion <strong>of</strong> the theory <strong>of</strong> typological markedness. Thetheory <strong>of</strong> typological markedness […] is a general theory <strong>of</strong> the relationshipbetween form <strong>and</strong> meaning across languages

The theory defines universal prototypes for the three major parts <strong>of</strong> speech, butdoes <strong>not</strong> define boundaries for these <strong>categories</strong>. Boundaries <strong>are</strong> aspects <strong>of</strong>language-particular grammatical <strong>categories</strong>, determined by distributionalanalysis”The typological universals do <strong>not</strong> predict the exact behaviour <strong>of</strong> individuallanguages; rather, they predict that a language will fit somewhere in the pattern <strong>of</strong>variation allowed by typological marking theoryThe behavioural potential criterion specifies that the unmarked memberdisplays at least as wide a range <strong>of</strong> grammatical behaviour as the markedmember. The behavioural potential criterion is again formulated as animplicational universal. It allows for the possibility <strong>of</strong> marked members […] tohave the same inflectional possibilities as unmarked members […] in somelanguage. It excludes the possibility <strong>of</strong> marked members having moreinflectional possibilities than unmarked members.The behavioural potential criterion also allows for the limited or “defective”behaviour <strong>of</strong> the marked member <strong>of</strong> a category […] without having to committo the marked member being “in” or “<strong>not</strong> in” the category in a universaltypologicalsense.

Moreover, the terms <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>adjective</strong> do <strong>not</strong> describe language-particulargrammatical <strong>categories</strong> anyway. They describe cross-linguistic patterns <strong>of</strong> variation.In particular they describe a prototype. A prototype describes the core <strong>of</strong> a category;it does <strong>not</strong> say anything about the boundary <strong>of</strong> a category […]. In fact, the universaltypological theory <strong>of</strong> parts <strong>of</strong> speech defines only prototypes for the parts <strong>of</strong> speech;it does <strong>not</strong> define boundaries. Boundaries <strong>are</strong> features <strong>of</strong> language-particular<strong>categories</strong>.<strong>Noun</strong> > reference to an objectAdjective > modification by a propertyVerb > predication <strong>of</strong> an action

In such a theoretical framework, we can<strong>not</strong> exclude cases <strong>of</strong> multiple classmembership <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> sporadic occurrence <strong>of</strong> linguistic constructions in atypicalroles.Cr<strong>of</strong>t (2000: 96)“it is quite common cross-linguistically to find a lexical item used in more thanone pragmatic function without overt derivation but with a significant <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>tensystematic semantic shift […]. The relevant cross-linguistic universal is thatthese shifts <strong>are</strong> always towards the semantic class prototypically associated withthe pragmatic function”

Lingue senza aggettivi?Mark Post (2008), Adjectives in Thai: Implicationsfor a functionalist typology od word classes,Linguistic Typology, 12:3, 339-381Lingue del Sud Est asiatico: senza aggettivi?No, se si assume l’idea che le parti del discorsosiano universalmente definite essenzialmente inbase alla condivisione di funzioni pragmatiche

Adjective classes <strong>are</strong> nowadays routinely identified as prototypicallycontaining words de<strong>not</strong>ing property concepts (p. 341)concetti graduabili: aggettiviconcetti non graduabili: nomi e <strong>verb</strong>iFundamentally, the semantic property <strong>of</strong> gradability would seem to lend<strong>adjective</strong>s an aptness for degree modification (more / less, a lot / little,the most / least), for lexicalization as points on a property scale (tiny,small, big, huge,…), as well as for comparison in terms <strong>of</strong> the relativedegree <strong>of</strong> properties exhibited by two referents (p. 341)

Dixon, R. M. W. (1977), Where have all the <strong>adjective</strong>s gone?, “Studies inLanguage”, 1, 19–80Dixon, R. M. W. / Aikhenvald, A. Y. (eds.) (2004), Adjective Classes. A Cross-Linguistic Typology, Oxford, Oxford University PressCORE:Dimension (big, small…)Age (new, old…)Value (good, bad…)Colour (black, white…)PERIPHERY:Physical property (hard, s<strong>of</strong>t…)Human propensity (happy, sad…)Speed (fast, slow…)Functionally, <strong>adjective</strong>s prototipically attribute features to a referent

Adjectives <strong>are</strong> <strong>of</strong>ten viewed as inherently mono-relational, in the semantic sensethat their de<strong>not</strong>ation may be viewed as incomplete without simultaneous construal<strong>of</strong> some entity or set which exhibits the stated property (e.g. a man who is tall), <strong>and</strong>in the syntactic sense that they either project (as predicate), cooccur with (ascopula complement), or depend on (a modifier) one <strong>and</strong> only one referringexpression.ThaiTerms de<strong>not</strong>ing properties <strong>are</strong> primarily divisible into-Verblike forms (the vast majority)- <strong>Noun</strong>like forms

Verblike properties include terms from all <strong>of</strong> the core <strong>and</strong> peripheral semantis fields:dii ‘good’jεεÎ ‘bad’rO´On ‘hot’naÍaw ‘cold’<strong>Noun</strong>like property concepts mainly correspond to the fields <strong>of</strong> PHYSICAL PROPERTY,HUMAN PROPENSITY, <strong>and</strong> COLOUR:thammachaÎat ‘natural(ness)’sùantua ‘private/privacy’saniÍm ‘rust(y)’

Proprietà distribuzionaliVerblike property concepts occur as intransitive predicate <strong>and</strong> do <strong>not</strong> occur ascopula complementKhon níi dəənCLF:person PRX walk‘This person walks’ (active <strong>verb</strong>, intransitive predicate)*Khon níi pen dəənCLF:person PRX ACOP walk‘This person walks’ (active <strong>verb</strong>, intransitive predicate)Khon níi diiCLF:person PRX good‘This person is good’ (<strong>verb</strong>like property term, intransitive predicate)*Khon níi pen diiCLF:person PRX ACOP good‘This person is good’ (<strong>verb</strong>like property term, intransitive predicate)PRX = proximate demonstrativeACOP = attributive copula

<strong>Noun</strong>like property concepts behave more like concrete <strong>and</strong> abstract nouns inoccurring as complement <strong>of</strong> an attributive copulaKhan níi pen sanǐmCLF:VEHICLE PRX ACOP rust(y)‘This vehicle is rusty’ (nounlike property term, copula complement)*Khan níi sanǐmCLF:VEHICLE PRX rust(y)Khon níi pen phará?CLF:PERSON PRX ACOP monk‘This man is a monk’ (concrete noun, copula complement)*Khon níi phará?CLF:PERSON PRX monk

Verblike property terms take direct <strong>verb</strong>al predicate negation in mâj ‘NEG’ whereasnounlike property terms, like nouns, again usually require support <strong>of</strong> a copula orother predicative functor.Ma c’è una costruzione in cui possano occorrere solo i cosiddetti <strong>verb</strong>like propertyterms o i cosiddetti nounlike property terms? Solo in questo caso potremmoconsiderarli una classe autonoma…All <strong>and</strong> only <strong>verb</strong>like property terms may uncontroversially occupy the positionprovisionally marked “x” in the b<strong>are</strong> comparative <strong>of</strong> a discrepancy construction;stative <strong>and</strong> active <strong>verb</strong>s can<strong>not</strong> usually occur in this position[NP1] [X] [COMP] [NP2]

Khon níi sǔuN kwàa khon nân[CLF:PERSON PRX] NP1[tall] X[more] COMP[CLF:PERSON DST] NP2‘This person is taller than that person’ (<strong>verb</strong>like property term)*khon níi khít/dəən kwàa khon[CLF:PERSON PRX] NP1[think/walk] X[more] COMP[CLF:PERSONnânDST] NP2‘This person thinks/walks more than that person (does)’ (stative/active <strong>verb</strong>s)DST = Distal demonstrativeSuch distributional differences [can be used] as evidence forthe coalescence <strong>of</strong> a distinct class <strong>of</strong> lexemes whose semanticcore is made up <strong>of</strong> property terms.

Khon níi sǔuN thâw khon nân[CLF:PERSON PRX] NP1[tall] Xequal [CLF:PERSON DST] NP2‘This person is tall as that person (is)’ (<strong>verb</strong>like property term)*khon níi khít thâw khon nân[CLF:PERSON PRX] NP1[think] Xequal [CLF:PERSON DST] NP2‘This person thinks/ as much as that person’ (stative/active <strong>verb</strong>s)DST = Distal demonstrative

Una parte del discorso non può essere chiusa: se esiste una classe di aggettivi,deve esistere anche il modo per form<strong>are</strong> nuovi aggettivi.nâa- “<strong>of</strong> an entity, have/be <strong>of</strong> a quality such that it seems like it would be nice toexperience interaction with in terms <strong>of</strong> VERB”thanǒn sên nân nâa-dəən kwàa sên níiroad CLF:LINE DST AZR-walk more CLF:LINE PRX‘That road looks more walkable (better or more suitable to walk on) than this one’châan- “having the characteristic <strong>of</strong> doing”khîi- “having the negative characteristic <strong>of</strong> doing”

“In terms <strong>of</strong> discourse funcionality, it is important to <strong>not</strong>e that adjectivaladnominal modification <strong>and</strong> /or attributive clause mentions most <strong>of</strong>ten occurredin the context <strong>of</strong> referent-introduction <strong>and</strong>/or description […], while <strong>verb</strong>aladnominal modifications <strong>and</strong>/or relative clause mentions most <strong>of</strong>ten occurredin the context <strong>of</strong> referent re-introduction <strong>and</strong>/or disambiguation […]. This wouldseem to relate to the facts that <strong>adjective</strong>s <strong>and</strong> attributive clauses bothprototypically refer to INHERENT PROPERTIES <strong>of</strong> entities – which could beexpected to occur in contexts <strong>of</strong> reference-fixing in initial mentions – while<strong>verb</strong>s <strong>and</strong> relative clauses both refer prototypically to SPECIFIC EVENTS inwhich entities participate, in contrast with other possible referents”

“There is a class <strong>of</strong> terms in Thai which closely resembles the <strong>adjective</strong> classes <strong>of</strong>many other languages in terms <strong>of</strong> semantic contents, internal structure, <strong>and</strong>distribution relative to other lexical classes, <strong>and</strong> this class should therefore bearthe label “<strong>adjective</strong>””Discovery <strong>of</strong> a linguistic universal “<strong>adjective</strong>s, properly defined, requiresestablishment <strong>of</strong> no single necessary <strong>and</strong> sufficient formal criterion such as“occurs as copula complement”; what it requires is the discovery that no languagefails to develop grammatical means <strong>of</strong> treating property concept words differentlyfrom other types <strong>of</strong> terms. The typological-oriented prediction <strong>of</strong> Dixon (2004) that<strong>adjective</strong>s (so defined) will be found in every language can be falsified throughdiscovery <strong>of</strong> a language in which property concept words <strong>are</strong> in fact NOT treatedin any way differently from a<strong>not</strong>her well-defined type <strong>of</strong> term (say, <strong>verb</strong> or noun).

Perceiving <strong>and</strong> naming actions <strong>and</strong> objectsM. Liljeström, A. Tarkiainen, T. Parviainen, J. Kujala, J. Numminen, J. Hiltunen,M. Laine, <strong>and</strong> R. SalmelinaNeuroImage 41 (2008) 1132–1141The existence <strong>of</strong> patients in whom focal brain damage is combined withselective impairments <strong>of</strong> grammatical <strong>categories</strong> has led to the suggestion thatthere <strong>are</strong> distinct cortical <strong>are</strong>as for processing <strong>verb</strong>s <strong>and</strong> nounsLesion data has implied a link between left frontal <strong>are</strong>as <strong>and</strong> <strong>verb</strong>processing, whereas noun processing seems to depend on the integrity <strong>of</strong>left temporal <strong>are</strong>as

<strong>Noun</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>verb</strong>s <strong>are</strong> distinguished in the brain on the basis <strong>of</strong> their semanticproperties, nouns typically referring to objects <strong>and</strong> <strong>verb</strong>s to actions.In the present fMRI experiment, healthy subjects were asked to silently nameactions <strong>and</strong> objects that were presented as simple line drawings. We used twosets <strong>of</strong> pictures, one depicting actions performed on/with objects <strong>and</strong> the otherdisplaying only the objects. Subjects named both actions <strong>and</strong> objects from theaction images, <strong>and</strong> objects from the object images. Actions were <strong>not</strong> namedfrom pictures with isolated objects, as this task would require the subject tomake inferences about the actions, a process <strong>not</strong> required in object naming. Thisdesign addresses the following questions:(i) Do action <strong>and</strong> object naming activate different cortical regions when thestimulus is identical?(ii) How does the content <strong>of</strong> the image (with/without action) modulate the braincorrelates <strong>of</strong> object naming?

The task was to silently name actions or objects from simple line drawings.Two sets <strong>of</strong> images were used, each with 100 scenes. Action images illustrateda simple event (e.g. to write with a pen) whereas object-only images consisted<strong>of</strong> objects from the same images when the action had been dissolved intoarbitrary lines in the background, in order to keep the visual complexity <strong>of</strong>the image unchanged.The corresponding object <strong>and</strong> action words were mostly <strong>of</strong> medium to highfrequency in the Finnish language.The <strong>verb</strong> <strong>and</strong> noun corresponding to one image always had different wordstems.

The experiment consisted <strong>of</strong> three conditions:(i) action naming from action images (Act),(ii) object naming from action images (ObjAct),(iii) object naming from object-only images (Obj).Task periods (30 s) <strong>and</strong> rest periods (21 s) alternated in a block design. Therewere two sessions, each lasting about 13 min.In order to avoid movement artifacts the participants were instructed to name theactions or objects silently. Subjects were asked to keep their eyes straight aheadduring the rest condition <strong>and</strong> <strong>not</strong> to move during the experiment.Results: A similar <strong>net</strong>work <strong>of</strong> cortical <strong>are</strong>as was activated in all three conditions,including bilateral occipitotemporal <strong>and</strong> parietal regions, <strong>and</strong> left frontal cortex.

The occipitotemporal cortex <strong>and</strong> the fusiform gyrus were activated bilaterally in allconditions. When actions or objects were named from action images (Act <strong>and</strong>ObjAct) the activation additionally encompassed the left posterior middletemporal cortex. Activation was seen in the left inferior frontal gyrus in all tasks.In both action <strong>and</strong> object naming from action images (Act <strong>and</strong> ObjAct) theactivation centered in the operculum <strong>of</strong> the inferior frontal gyrus <strong>and</strong> extendedsuperiorly to include the precentral gyrus <strong>and</strong> anteriorly to BA 47. The frontalactivation was less pronounced when objects were named from object-onlyimages (Obj), mainly encompassing the inferior frontal region.

Naming objects from the images with action context comp<strong>are</strong>d to naming the sameobjects from object-only images (ObjActNObj, Fig. 3B) resulted in significantlystronger activation in a large mostly left-lateralized <strong>net</strong>work, including the precentralgyrus (BA 6/9), the inferior frontal gyrus (pars opercularis <strong>and</strong> triangularis), theinferior <strong>and</strong> superior parietal lobules (BA 7/40), <strong>and</strong> the posterior middle temporalgyrus. Naming actions comp<strong>are</strong>d to naming objects from object-only images(ActNObj, Fig. 3C) revealed enhanced activation in the left supramarginal gyrus(parieto-temporal junction; BA 40), left <strong>and</strong> right posterior middle temporal cortex,left precentral gyrus <strong>and</strong> superior medial frontal gyrus.Our results indicate that action <strong>and</strong> object naming engage a common cortical<strong>net</strong>work, but that the provided input (action pictures, object-only pictures) <strong>and</strong> therequested output (<strong>verb</strong>, noun) influence the level <strong>of</strong> activation in a subset <strong>of</strong><strong>are</strong>as within that <strong>net</strong>work.The stronger activation in naming objects from pictures with action context,relative both to naming actions from the same images <strong>and</strong> to naming objectsfrom object-only pictures, suggests involvement <strong>of</strong> additional task-specificprocesses.

We found no regions specific to nouns as a grammatical category. Our resultsagree with a recent study showing that when naming events either as <strong>verb</strong>s ornouns from identical images, no differences were found between <strong>verb</strong>s or nounsas grammatical <strong>categories</strong>.Our results converge with previous evidence showing that retrieval <strong>of</strong> <strong>verb</strong>s <strong>and</strong>nouns in the healthy human brain using identical stimuli in a picture naming taskengages a similar distributed cortical <strong>net</strong>work, as measured with BOLD fMRI.Importantly, however, the content <strong>of</strong> the image (action vs. object only) had apronounced effect on the activation in parts <strong>of</strong> that <strong>net</strong>work that have previouslybeen implicated in processing <strong>of</strong> action knowledge. Furthermore, object naming inthe context <strong>of</strong> action revealed additional activations, both in comparison to <strong>verb</strong>retrieval from the same set <strong>of</strong> images, <strong>and</strong> in comparison to noun retrieval fromimages <strong>not</strong> depicting action, suggesting that attention may be more directedtowards motor-based properties <strong>of</strong> objects when they <strong>are</strong> presented <strong>not</strong> as singleentities but as part <strong>of</strong> images that also depict the relevant action.

“The term coordination refers to syntactic constructions in which two ormore units <strong>of</strong> the same type <strong>are</strong> combined into a larger unit <strong>and</strong> stillhave the same semantic relations with other surrounding elements”Haspelmath, M. (2004), "Coordinating constructions: An overview", inHaspelmath, M. (ed.), Coordinating constructions, Amsterdam, Benjamins, 3-39.“A coordinating construction consists <strong>of</strong> two or morecoordin<strong>and</strong>s, i.e. coordinated phrases. Their coordinate status maybe indicated by coordinators, i.e. particles like <strong>and</strong>, or <strong>and</strong> but, oraffixes like Chechen –ii (e.g. shyyr-ii dik-ii ‘thick <strong>and</strong> good’ […]). Ifone ore more coordinators occur in a coordinating construction, it iscalled syndetic.”

North Caucasian, East Caucasian, Nakh, Chechen-Ingush

Asyndetic coordination consists <strong>of</strong> simple juxtaposition <strong>of</strong> the coordin<strong>and</strong>s:Lavukalevenga-bakala nga-uia tula1SG.POSS-paddle(M) 1SG.POSS-knife(F) small.SG.F'my paddle <strong>and</strong> my small knife'East Papuan, Yele-Solomons-New Britain, Yele-Solomons, CentralSolomons

Two types <strong>of</strong> syndesis can be distinguished: monosyndetic coordination,which involves only a single coordinator (when <strong>not</strong> more than two coordin<strong>and</strong>s<strong>are</strong> present):Iraqwkwa/angw nee du'umaH<strong>are</strong> <strong>and</strong> leopard'the h<strong>are</strong> <strong>and</strong> the leopard'Afro-Asiatic, Cushitic, South

isyndetic coordination involves two coordinators:Upper Kuskokwim AthabaskanDineje i« midzish i«Moose with caribou with‘moose <strong>and</strong> caribou’Na-Dene, Nuclear Na-Dene, Athapaskan-Eyak, Athapaskan, Tanana-UpperKuskokwim, Upper Kuskokwim

Three different semantic types <strong>of</strong> coordination <strong>are</strong> usually distinguished:Conjunction (= conjunctive coordination, '<strong>and</strong>' coordination)Persian (Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Iranian, Western, Southwestern, Persian)tir=okæmanarrow=<strong>and</strong> bow'bow <strong>and</strong> arrow'Disjunction (=disjunctive coordination, 'or' coordination)IraqwTsíiyáhh laqáa tám laqáa tsárFour or three or two'four or three or two'Adversative coordination ('but‘ coordination)LavukaleveOina sou fale-re kini a-e-ve-meo<strong>not</strong>her.SG.M rise st<strong>and</strong>-NONFIN ACT 3SG.M.O-SBD-go-SURPtaman lake ga e-nua-ri-re...But road(N) SG.N.ART 3SG.N.O-be.amiss-CAUS-NONFIN‘He stood up, but he took the wrong path…’

The position <strong>of</strong> the coordinator(s)In monosyndetic coordination, there <strong>are</strong> four logically possible types:A <strong>and</strong> B st<strong>and</strong> for two coordin<strong>and</strong>sco st<strong>and</strong>s for the coordinator.In descending order <strong>of</strong> cross-linguistic frequencya. [A] [co B] e.g. Hausa Abdù dà Feemì 'Abdu <strong>and</strong> Femi'b. [A co] [B] e.g. Lai vòmpii=lee phètee 'a bear <strong>and</strong> a rabbit'c. [A] [B co] e.g. Latin senatus popolus-que romanus'the senate <strong>and</strong> the Roman people'd. [co A] [B]???The fourth type seems to be unattested, <strong>and</strong> the third type is very r<strong>are</strong>

Hausa: Afro-Asiatic, Chadic, West

Lai / Chin Haka: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman,Kuki-Chin-Naga, Kuki-Chin, Central

In English <strong>and</strong> other European languages, there is a single conjunctivecoordinator '<strong>and</strong>' whose use is independent <strong>of</strong> the meaning <strong>of</strong> the conjuncts orany semantic nuances <strong>of</strong> conjunction that might be conveyed. But manylanguages have different conjunctive constructions depending on semanticfactorsanimacy <strong>of</strong> the conjuncts: Takiao ai da2SG 1SG COM'you <strong>and</strong> I'Meit Kabun daM. K. COM'Meit <strong>and</strong> Kabun‘vs.mau dabel fudtaro yam banana'taro, yam <strong>and</strong> banana'

proper names <strong>and</strong> common nouns: AsmatPisím enerím WasíPisím <strong>and</strong> Wasí‘vs.onów am, ós amthatch <strong>and</strong> wood <strong>and</strong>'thatch <strong>and</strong> wood'

Takia: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Central-Eastern, Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, Oceanic, Western Oceanic, North New Guinea, Ngero-Vitiaz,Vitiaz, Bel, Nuclear Bel, NorthernAsmat: Trans-New Guinea, Main Section, Central <strong>and</strong> Western, Central <strong>and</strong> SouthNew Guinea-Kutubuan, Central <strong>and</strong> South New Guinea, Asmat-Kamoro

conceptual unit vs. separate entities.Chechen A-ii B-ii vs. A 'a B 'ashish-ii stak-ii'a bottle <strong>and</strong> a glass‘vs.waerzha mazh 'a, q'eegash shi bwaerg 'a'a black beard <strong>and</strong> two shining eyes'Cfr. anche:tight vs. loose coordinationTight coordinators <strong>are</strong> used with items that can be thought <strong>of</strong> as couples orpairs which <strong>are</strong> closely associated in the real worldLoose coordinators <strong>are</strong> used with items which <strong>are</strong> less closely associated.Lenakeltight m = nmataag m nihin 'wind <strong>and</strong> rain‘vs.loose mne = kuri mne pukas 'a dog <strong>and</strong> a pig'

Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian,Central-Eastern,Eastern Malayo-Polynesian,Oceanic,Central-Eastern Oceanic,South Vanuatu, Tanna