Chapter 128

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Consent, Research, and<br />

Withdrawing Treatment<br />

Nicholas Pace and David A. Blacoe<br />

<strong>128</strong><br />

CHAPTER<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Ethical and legal principles have always been of paramount<br />

importance to the medical profession, because they determine<br />

how it ought to behave. Ethical principles can be summarized into:<br />

respect for autonomy, beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do<br />

not harm) and justice (resources have to be distributed fairly)<br />

(Table <strong>128</strong>–1). Of these, the principle of respect for autonomy is<br />

now generally regarded as the central ethical principle in medical<br />

practice. Society today places great emphasis on the value and<br />

dignity of the individual and gives issues of consent and selfdetermination<br />

an emphasis they have never previously been<br />

afforded. This has arisen from the concept of natural rights, which<br />

dictate that a competent person should decide what happens to<br />

his or her body.<br />

These principles and issues are not just applicable to adults. The<br />

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)<br />

is an international human rights treaty that grants all children<br />

and young people (aged 17 years and less) a comprehensive set<br />

of rights. It is presently the most widely ratified international<br />

human rights treaty and has been signed by all UN member states<br />

except for the United States and Somalia. It came into force in<br />

September 1990.<br />

The UNCRC is the only international human rights treaty to<br />

include civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights, and<br />

sets out in detail what every child needs to have a safe, happy,<br />

and fulfilled childhood. It also takes into account children’s<br />

need to have special assistance and protection because of their<br />

vulnerability.<br />

The convention gives children and young people more than 40<br />

substantive rights. In particular, it includes the right to be informed<br />

about and participate in achieving their rights in an accessible and<br />

active manner. Thus, it gives children greater autonomy and an<br />

increased role in decision-making.<br />

This chapter will examine the ethical and legal implications of<br />

consent, informed consent, research, and withholding and withdrawing<br />

treatment relating to pediatric anesthesia. It will also<br />

briefly discuss the controversial issue of fetal rights. For simplicity<br />

in this chapter, a child is referred to as female.<br />

CONSENT IN CHILDREN<br />

Legal Definition of Consent and Competence<br />

Doctors and other healthcare staff cannot do anything to<br />

competent patients without their consent, because the right to<br />

consent or refuse treatment is grounded in the ethical principle of<br />

respect for autonomy and the right to self-determination. Consent<br />

is the patient’s voluntary agreement to treatment, examination, or<br />

any other aspect of health care. 1 There are legal consequences for<br />

an unauthorized invasion of bodily integrity. If no legally effective<br />

consent has been given, a doctor will be liable for civil or even<br />

criminal charges of assault if he makes contact with the patient. 2<br />

However, such consent does not provide a defense to a claim that<br />

the doctor negligently advised a particular treatment or negligently<br />

carried it out.<br />

The common law has long recognized the principle that every<br />

person has the right to have his bodily integrity protected against<br />

invasion by others. The classic expression underlying this<br />

sentiment is that of Justice Cardozo:<br />

“Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to<br />

determine what shall be done with his own body; and a surgeon<br />

who performs an operation without the patient’s consent commits<br />

an assault.” 3<br />

In order for the consent of any individual to be valid, five<br />

conditions need to be met. The patient must be competent,<br />

information needs to be disclosed and understood, the consent<br />

must be given voluntarily, and finally, the patient must give<br />

authorization (Table <strong>128</strong>–2).<br />

Competence is fundamental to the practice of obtaining<br />

consent. It means the ability to perform a task and involves the<br />

ability to understand information, retain that information, and<br />

use that information to come to a decision. It is not an allor-nothing<br />

phenomenon and relates to a particular situation. A<br />

patient may thus be competent in one setting—for example, taking<br />

a hearing test—but not in another, such as consenting to heart<br />

surgery. A patient may not be competent to make a decision (and<br />

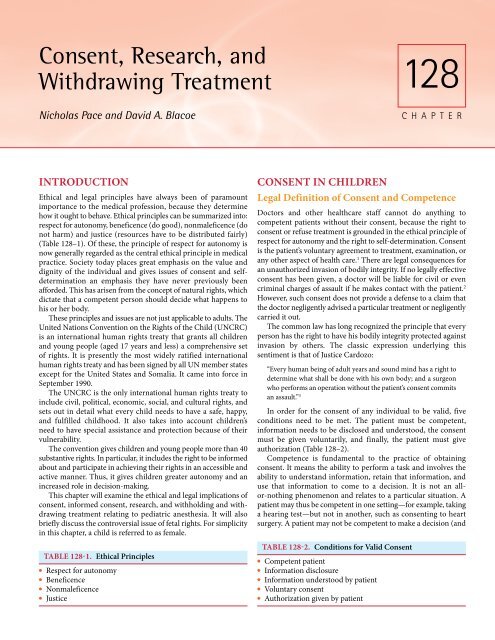

● Justice ● Authorization given by patient<br />

TABLE <strong>128</strong>-2. Conditions for Valid Consent<br />

TABLE <strong>128</strong>-1. Ethical Principles<br />

● Competent patient<br />

● Respect for autonomy<br />

● Information disclosure<br />

● Beneficence<br />

● Information understood by patient<br />

● Nonmaleficence<br />

● Voluntary consent

2110 PART 6 ■ Specific Considerations<br />

therefore not able to give consent) because of unconsciousness or<br />

because they are too young. In such situations, a proxy may give<br />

consent. However, proxy consent is legally valid only when the<br />

patient gives express authority to another person to give or<br />

withhold consent on his or her behalf or when the law invests a<br />

person with such power. The commonest example of the latter is<br />

that of parent and child. However, when proxy consent of this sort<br />

is available, the person vested with that power must use it<br />

reasonably. Consent for treatment of a minor can be obtained<br />

from one of three authorities: the competent child, the child’s<br />

parents or guardians, or the courts. Where medical and parental<br />

opinion differ, the doctor administering emergency life-saving<br />

treatment without parental consent will traditionally be supported<br />

by common law. In all but the most urgent of circumstances,<br />

disputes over care should be referred to the courts. 4<br />

Recent statutory reforms in England and Wales (Mental Capacity<br />

Act 2005) and in Scotland (Adults with Incapacity (Scotland)<br />

Act 2000) have simplified the management of consent issues with<br />

respect to incapable adults. 1 No such legislation exists in regard to<br />

consent in children and it should therefore be immediately clear<br />

that this raises many legal and ethical dilemmas.<br />

Age of Competence to Give Consent<br />

The first matter to be decided is at what age a child becomes an<br />

adult. This age, in most European jurisdictions, is 18 years old.<br />

A person older than this age, provided they are not mentally<br />

incapacitated, has the right to make decisions regarding their<br />

medical treatment and, indeed, may refuse what is offered. Thus,<br />

even if the treatment proposed is clearly in that patient’s interests<br />

and may even save that patient’s life, the patient has a right to<br />

refuse it. Once a child reaches this age, she is given legal rights to<br />

make decisions and may give or refuse consent to whatever<br />

medical treatment she wishes.<br />

This does not mean that a child that has not yet reached this age<br />

has no legal or ethical rights. Various legal systems throughout the<br />

Western world have embraced the concept of the “mature” or<br />

“emancipated” minor, with the consequent legal capacity to consent<br />

to medical treatment. That is, beyond a certain age and level<br />

of mental maturity, a child is able to make a decision regarding<br />

her own treatment. This is in keeping with the UNCRC as<br />

described earlier. This asserts a child’s right to have her views<br />

accorded due weight in relation to her age and maturity. 5<br />

In the Canadian case of Johnston v. Wellesley Hospital, 6 the<br />

plaintiff sued for damages caused to the skin of his cheeks and<br />

forehead by the treatment used by the defendant, Wellesley. One<br />

of the questions raised was whether a 20-year-old person could<br />

consent to treatment when at that time the age of majority in<br />

Canada (the magical age described earlier) was 21 years. The judge<br />

stated that if a minor was old enough to appreciate fully the nature<br />

and consequences of the proposed treatment, then he could give<br />

effective consent. In another Canadian case the trial judge took<br />

into account the child’s sincerity, maturity, and forthrightness<br />

and respected the child’s wishes rather than those of her legal<br />

guardians. 7<br />

The consequences of the Johnston decision were far-reaching<br />

and it has been directly quoted in a number of cases in other<br />

jurisdictions. It had a direct bearing on the widely known English<br />

case of Gillick v. West Norfolk Area Health Authority. 8 Before this<br />

case, despite the age of majority being 18 years, the Family Law<br />

Reform Act, section 8, subsection 1 (1969), had decreed that once<br />

a person reached the age of 16 years, he or she could consent to any<br />

surgical, medical, or dental treatment. In other words, adult status<br />

was reached at 16 for the purpose of medical treatment and it was<br />

therefore not necessary to obtain consent from the parent. The<br />

Gillick case concerned the validity of consent, without parental<br />

knowledge, to contraceptive treatment from a child who was<br />

younger than 16. The House of Lords ruled that a child younger<br />

than 16 years could give valid consent to medical treatment<br />

without parental consent, provided the child, in the opinion of the<br />

doctor, was of sufficient maturity and intelligence to understand<br />

the implications of the treatment proposed.<br />

It would therefore be up to the individual doctor to decide<br />

whether a child younger than 16 years of age could give valid<br />

consent. The basis on which this decision is to be made is, unfortunately,<br />

ill defined. It is unlikely this decision will be challenged if<br />

made in good faith. However, should it be challenged, then the<br />

normal rules of negligence will apply. So, in the United Kingdom,<br />

if a responsible body of medical opinion, which also withstands<br />

logical judicial analysis, 9 agreed that the child was competent to<br />

give consent, the action against the doctor will fail. Thus, in difficult<br />

cases, advice from colleagues should be sought. In certain situations,<br />

such as various heart or neurologic operations, it would be<br />

highly unlikely that a child could give effective consent. Giesen, an<br />

authority on medical malpractice law, believes that when the<br />

minor’s own future welfare is at stake and the consequences of the<br />

procedure might be serious, traumatic, or irreversible, physicians<br />

should generally seek parental cooperation. 10<br />

In principle, however, the age at which a minor is considered<br />

competent to give, but not necessarily to withhold, consent varies<br />

across Europe from 14 to 18 years of age. The assessment of<br />

competence is dependent on the nature of the proposed procedure,<br />

the complexity of the decision process, and the gravity of associated<br />

implications. Thus, the graver the impact of the decision, the<br />

commensurately greater the competence needed to make it. 11<br />

Even if the child is deemed not to be of sufficient maturity to<br />

consent, it is important that the child participates in the decisionmaking<br />

process. Thus, in Canada, a child over the age of 8 years<br />

must discuss the decision regarding treatment, although the<br />

final decision is not hers. A similar situation exists in the United<br />

Kingdom 12 and almost certainly applies in other countries, at least<br />

from an ethical if not legal standpoint.<br />

Refusal of Consent by a Minor<br />

Autonomy means that a competent adult patient has the right to<br />

give or withhold consent to investigation or treatment, irrespective<br />

of any untoward consequences. Furthermore, an adult patient is<br />

not restricted to accept or refuse what is on offer, but should be<br />

allowed to choose the type and scope of treatment and to base this<br />

inadequate information about success rates and risks and what<br />

impact they may have on daily living. A competent adult is<br />

perfectly entitled to reject medical advice. If contemplated by a<br />

minor, however, it is understandably much more problematic,<br />

especially if the consequences are serious. Following decisions<br />

such as Gillick, it would appear logical that a child has every right<br />

to refuse treatment, provided she has sufficient maturity and<br />

intelligence to understand the implications of refusing the<br />

treatment proposed. If one is legally entitled to consent, one must<br />

be legally entitled to dissent, 13 a situation analogous to the adult

CHAPTER <strong>128</strong> ■ Consent, Research, and Withdrawing Treatment 2111<br />

situation. Once again, as discussed above, the judgment regarding<br />

competence is to be made by the physician, with advice from<br />

colleagues in difficult cases.<br />

However, it would appear that in many jurisdictions a minor<br />

cannot refuse treatment that in the opinion of the medical profession<br />

or courts is in her best interests. Several test cases have<br />

established this precedent. 14<br />

The English case of Re R 15 concerned a 15-year-old whose<br />

disturbed behavior required sedation. However, when lucid and<br />

competent, she refused her medication. The judges held that the<br />

court could override the refusal of treatment if that was considered<br />

to be in her best interests. Further, the judges suggested that the<br />

parental right to give consent in the face of the child’s refusal was<br />

retained. This was further considered in the case of Re W. 16 This<br />

concerned a 16-year-old suffering from anorexia nervosa who was<br />

refusing all treatment. Lord Donaldson stated:<br />

“No minor of whatever age has power by refusing consent to<br />

treatment to override a consent to treatment by someone who has<br />

parental responsibility for the minor …”<br />

Clearly, in both cases, the judges were concerned of the need to<br />

protect the medical profession from litigation. However, both<br />

cases were unusual in that they dealt with diseases that could<br />

impair reasoning. The case of Re M 17 demonstrates the furthest<br />

extremes to which these powers have been tested. M, a 1-year-old<br />

girl, refused consent for a heart transplant in the face of lifethreatening<br />

disease. Justice Johnson emphasized the need to take<br />

account of the mature minor’s wishes, but that these wishes were<br />

in no way determinative, and held that the proposed treatment<br />

was in the minor’s best interest and should proceed. M agreed to<br />

comply after this ruling so the final need to enforce treatment was<br />

averted, although Justice Johnson still expressed concern at the<br />

gravity of his decision.<br />

Thus, it would appear that a child is mature enough to make a<br />

decision regarding treatment only if her decision agrees with that<br />

of the courts and medical profession. This is arguably illogical, and<br />

such decisions have been widely criticized. The counter argument<br />

is that the potential consequences of refusal of consent (such as<br />

immediate harm or limitation of future choices) are not necessarily<br />

equal to those of giving consent. The implications of refusal<br />

may, therefore, be more serious, and on these grounds refusal of<br />

treatment may require a greater understanding and comprehension<br />

than does acceptance of medical advice: the two conditions<br />

therefore cannot be regarded as being on a par.<br />

From an ethical viewpoint, the focus is changing from a<br />

doctor’s obligation to disclose information to the quality of the<br />

patient’s understanding. Understanding the information provided<br />

is a more important element than the mere disclosure of that<br />

information. Many conditions, such as illness, can limit a patient’s<br />

understanding. Most important from this chapter’s perspective is<br />

the fact that immaturity can also limit understanding.<br />

In all the above cases, the judges emphasized the importance of<br />

respecting the minor’s wishes and of giving them increasing value<br />

with increasing maturity. The concept of the mature minor should<br />

therefore be breached only in exceptional circumstances. 18<br />

In summary, at least in England, when a child reaches the age<br />

of 16, his or her consent will be valid for treatment. This will be<br />

overturned if the patient is not competent to consent. Below the<br />

age of 16, doctors must assess the particular child‘s capacity to<br />

consent in relation to the proposed intervention. This involves the<br />

ability to understand that there is a choice and that choices have<br />

consequences. There must be a willingness and ability to make a<br />

choice. There must be an ability to understand the nature and<br />

purpose of the proposed procedure and the available alternatives,<br />

including a proper assessment of the risks and side effects 19<br />

inherent in these alternatives.<br />

To confuse the issue, the above does not apply to Scotland. In<br />

Scotland, if a competent child refuses treatment or investigations,<br />

this should be accepted in the same way as an adult refusal. The<br />

only reported case is that of a 15-year-old boy with a psychotic<br />

illness who refused to remain in hospital for treatment. Despite<br />

his mother giving consent, the sheriff ruled that logic demanded<br />

that the decision of a competent young person could not be<br />

overruled by a parent. 20 Treatment was, however, subsequently<br />

enforced under the Mental Health (Scotland) Act of 1984, 20 and as<br />

such the sheriff was able to avoid the immediate implications of<br />

the decision. The Scottish courts have made no definitive ruling<br />

on this matter, and a case falling out with the remit of the Mental<br />

Health Act has yet to be tested.<br />

It is therefore clear that practitioners should review each case<br />

carefully and in cases of doubt seek legal advice. The problem<br />

revolves around the evaluation of competence. Unfortunately,<br />

there do not appear to be any guidelines on how this can be<br />

measured and utilized. It is for the doctor to decide whether a<br />

minor is competent or not, and it would appear that if this is<br />

challenged, the final arbiter would be whether a responsible body<br />

of medical opinion would support the decision. Clearly this is very<br />

much a gray area in terms of legal obligations, but it appears that<br />

the law is taking a back seat and allowing the medical profession<br />

to make these decisions. Such a situation, clearly, may change if a<br />

controversial case comes before the courts.<br />

Parental Refusal of Consent<br />

for Life-Saving Treatments<br />

The question of parental refusal of treatment also creates uncertainty,<br />

especially because frequently there are religious reasons for<br />

this. It is of particular concern to anesthesiologists, because such<br />

examples include refusal of blood transfusions by parents who are<br />

Jehovah’s Witnesses. It should be remembered that overriding<br />

religious convictions is a major step to take in a free society. It also<br />

significantly interferes with the principle that parents should have<br />

the freedom to choose the religious and social upbringing of their<br />

children. 21 However, as mentioned earlier, the person vested with<br />

the power of proxy consent must use it reasonably, and in these<br />

cases the well-being of the child is paramount. Thus, parental<br />

refusal of life-saving treatment is routinely disregarded and the<br />

law has virtually always given consent for the transfusion, overriding<br />

parental objection. It is suggested that the approval of a<br />

court of law should be sought before such an administration. It is<br />

also suggested that two doctors of consultant status should make<br />

an unambiguous, clear, and signed entry in the clinical record that<br />

blood transfusion is essential, or likely to become so, to save life or<br />

prevent serious permanent harm. 22 The parents should be given<br />

the opportunity to be properly represented and be kept fully<br />

informed of the doctor’s intention to apply for a court order. 23 In<br />

an emergency, where there is no time to obtain court approval,<br />

health professionals should proceed with life-saving treatment<br />

under the doctrine of necessity.<br />

Despite the assumption that life saving treatment can be<br />

administered against the wishes of the parents, several cases have

2112 PART 6 ■ Specific Considerations<br />

also established the precedent that, in some situations, parents can<br />

legally refuse consent to treatment of their child. In one case, a<br />

mother refused chemotherapy for her 3-year-old child who was<br />

suffering from cancer. The hospital took the mother to court. The<br />

court upheld the mother’s decision, because the judges felt there<br />

was only a small chance of recovery and also because of the severe<br />

side effects that would result from chemotherapy. 24 Thus, it is<br />

impossible to set hard and fast rules. Each case should be analyzed<br />

on its own merits. What is clear is that if treatment is immediately<br />

necessary to preserve life, doctors should proceed with treatment.<br />

If treatment is not immediately required, then referral to a court<br />

of law should be undertaken. Doctors can only act in defiance of<br />

parental views in the emergency situation.<br />

Nontherapeutic Circumcision<br />

An issue directly applicable to anesthesiologists is that of nontherapeutic<br />

circumcision. Female circumcision, which involves<br />

suffering, mutilation, and serious health risks, is illegal under U.K.<br />

law 25 and will not be discussed further. The issues surrounding<br />

male circumcision, on the other hand, are less clear and require<br />

further analysis. In children, this virtually always relies on parental<br />

consent and is usually carried out for ritual, social, or cultural<br />

reasons. Brazier has commented that male circumcision is a matter<br />

of medical debate and for Jewish and Muslim parents it is an article<br />

of faith. She argues that the child suffers momentary pain and,<br />

although medical opinion may not necessarily regard circumcision<br />

as positively beneficial, it is in no way medically harmful if<br />

properly performed. The community as a whole, she claims,<br />

regards it as a decision for the infant’s parents. 26<br />

These arguments can be challenged. Firstly, there is extensive<br />

literature on the harms of circumcision. 27,28 It is also not clear from<br />

her argument how the operation can be justified legally and<br />

ethically. If the principal starting points are that everyone has a<br />

right to bodily integrity and that proxy consent has to be used<br />

reasonably and in the interests of the child, then it is possible that<br />

the procedure cannot be justified. It is also self-evident that any<br />

future choice is limited once the procedure is undertaken.<br />

The ethical justification for circumcision is that it is in the<br />

child’s best interests because it facilitates social acceptance rather<br />

than exclusion and enhances cultural identity and belonging. The<br />

degree of social acceptance or exclusion inferred is variable, and<br />

this should be considered when weighing up what is in the boy’s<br />

best interest: the child in an orthodox Jewish or Muslim culture<br />

has a very different perspective from one whose parents wish him<br />

to be circumcised simply to be like his father. Parental preference<br />

alone would not pass the “best interests” test. On a practical level,<br />

there is an argument that denying access to medical circumcision<br />

will result in greater harm by encouraging illegal circumcision in<br />

an unhygienic environment by unskilled practitioners. This is a<br />

weak argument, however, as it can also be used to justify very<br />

harmful practices, such as female genital mutilation and ritual<br />

sacrifice, which should be prevented by law rather than by the<br />

permission of a lesser evil.<br />

As previously argued, it is clear that parental rights are derived<br />

from parental duty and exist only so long as they are needed for<br />

the protection of the person and property of the child. Giving<br />

consent to medical treatment of a child is a clear example of<br />

parental responsibility arising from the duty to protect the child. 29<br />

The rights reside in the child with the parents acting as agents for<br />

the child to enforce those rights. 30 Even the argument utilized later<br />

in nontherapeutic research, that it may be acceptable as long as it<br />

is not against the interests of the child, fails because of the potential<br />

harms caused.<br />

In Australia, the Queensland Law Reform Commission stated:<br />

“Unless there are immediate health benefits to a particular child<br />

from circumcision, it is unlikely that the procedure itself could be<br />

considered therapeutic … The circumcision is invasive, irreversible<br />

and major. It involves the removal of an otherwise healthy organ<br />

part. It has serious attendant risks … On a strict interpretation of<br />

the assault provisions of the Queensland Criminal Code, routine<br />

circumcision of a male infant could be regarded as a criminal act.<br />

Further, consent by parents to the procedure being performed may<br />

be invalid in the light of the common law’s restrictions on the ability<br />

of parents to consent to the non-therapeutic treatment of children.”<br />

In the United Kingdom, male nontherapeutic circumcision is<br />

generally assumed to be lawful provided it is performed<br />

competently, there is valid consent, and it is believed to be in the<br />

child’s best interests. Judicial review has shown that this is “an<br />

exercise of joint parental responsibility” and as such both parents<br />

must give consent. 31,32 The term “best interest” encompasses<br />

medical, emotional, and all other welfare issues, and it should be<br />

noted that, at least for incapable adults, it is for a judge, not the<br />

doctor, to finally determine what is in the best interests of the<br />

person concerned. 33<br />

The legal standing on nontherapeutic circumcision may be<br />

affected by the Human Rights Act, which, in 2000, incorporated<br />

Articles of the European Convention on Human Rights 34 into U.K.<br />

Law. Rights that may be relevant are:<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

●<br />

Article 3: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or<br />

degrading treatment or punishment.”<br />

Article 5(1): “Everyone has the right to liberty and security of<br />

the person.”<br />

Article 8: “Everyone has the right to respect for his private and<br />

family life” except for the “protection of health or morals, or for<br />

the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”<br />

Article 9(1): “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience<br />

and religion.”<br />

Article 9(2): “Freedom to manifest one’s religion or beliefs shall<br />

be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and<br />

are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of public<br />

safety, for the protection of public order, health or morals, or for<br />

the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”<br />

As yet, the full impact of the Human Rights Act on medical<br />

decision-making is still to be determined. If medical evidence were<br />

conclusive in showing that circumcision is prejudicial to a child’s<br />

health or welfare then it is likely a legal challenge on human rights<br />

grounds would be successful, and indeed that there may be obligations<br />

on the state to proscribe it. 35 As always, legal advice should<br />

be sought if there is any doubt over the legality of proceeding with<br />

treatment.<br />

Finally, those in favor of continuing with this practice need to<br />

answer one further question; why can’t the procedure wait until<br />

the child is old enough to make his own decision?<br />

Parental Presence in the Anesthetic<br />

and Resuscitation Rooms<br />

The issue of parental presence in the anesthetic room and<br />

resuscitation room has also been raised recently. Some argue that

CHAPTER <strong>128</strong> ■ Consent, Research, and Withdrawing Treatment 2113<br />

a parent has a right to be present during the resuscitation of his or<br />

her child, if they so wish. Others argue that the experience of<br />

seeing one’s child in such a desperate situation (particularly during<br />

resuscitation) is likely to cause serious emotional trauma, immediately<br />

and in later life. Whenever possible, the wishes of the<br />

parents should be respected, however, the anesthesiologist or<br />

resuscitation coordinator should have the final veto. This situation<br />

has not, as yet, been challenged in the courts.<br />

Transplantation<br />

The first kidney transplants were undertaken between identical<br />

minors. Couples are now having children for the express purpose<br />

of providing genetically compatible sibling donors of, at present,<br />

regenerative tissue. Whether these practices are ethically and<br />

legally acceptable is debatable, but it appears that they are likely<br />

to increase. Different legal jurisdictions have come to different<br />

conclusions about their acceptability. In Canada, the Ontario<br />

Human Tissue Gift Act (C.C.S.M. c. H180. June 16, 2005) provides<br />

statutory prohibition of donation by minors. In Australia it is not<br />

lawful to remove nonregenerative material from a living child for<br />

the purpose of transplantation. There are also certain qualifica -<br />

tions relating to the donation of regenerative tissue. The law in<br />

France appears to provide a slightly different solution. There, a<br />

living minor may donate, but only to a sibling. Furthermore,<br />

consent must be given by the donor’s legal representative. The<br />

procedure must then be authorized by an “ethics committee”<br />

comprised of at least three experts, two of whom must be doctors,<br />

one of whom must have at least 20 years of experience.<br />

The U.K. situation is, once again, unclear. The Human Tissue<br />

Act 2004 simply states that, regarding child donors, “appropriate<br />

consent” must be obtained, defined as the child’s own consent or,<br />

if incompetent, consent of a person who has parental responsibility.<br />

36 It would appear, from the arguments discussed earlier, that<br />

the “Gillick” competent minor would be able to consent, subject to<br />

the restrictions of the minor’s understanding the risks and benefits<br />

involved. Clearly, donation of nonregenerative organs involves<br />

greater risks than removal of those that can be replaced. Similarly,<br />

the risks inherent in the surgery to obtain the organs are relevant.<br />

Thus, it is far riskier to obtain a part of a liver than to obtain bone<br />

marrow, despite both being capable of regeneration. However,<br />

Lord Donaldson stated that:<br />

“It is inconceivable that [the doctor] should proceed in reliance<br />

solely upon the consent of an under-age patient, however ‘Gillick<br />

competent’ in the absence of supporting parental consent<br />

and equally inconceivable that he should proceed in the absence<br />

of the patient’s consent. In any event he will need the opinion of<br />

other doctors and may well be advised to apply to the court for<br />

guidance …”<br />

The situation regarding incompetent minors is even more<br />

unclear. The debate hinges around whether parents have the right<br />

to consent on behalf of their child to something that will not<br />

benefit, and may indeed harm, the child. Once again, the separation<br />

into regenerative and nonregenerative tissue may help to<br />

assess what would be an acceptable risk. The Council of Europe<br />

Protocol on Transplant of Organs states that removal of regenerative<br />

tissue from a person who does not have the capacity to<br />

consent may be authorized provided no other capable donor is<br />

available, the recipient is a sibling, the donation has life saving<br />

potential for the recipient, authorization has been given by<br />

the donor’s representative or body empowered by law, and the<br />

potential donor does not object. 37<br />

Assessment of what benefit would accrue to the child, such as<br />

survival of a sibling or parent, will also need to be undertaken. It<br />

is suggested that application to the courts would be needed in<br />

virtually all cases in the United Kingdom.<br />

INFORMED CONSENT IN CHILDREN<br />

The Concept of Informed Consent<br />

All medical codes of ethics hold that physicians have a duty to<br />

obtain the informed consent of patients before undertaking<br />

procedures. Thus, there is an obligation to disclose information,<br />

ensure the patient understands the information and, to the best of<br />

their ability, ensure consent is given voluntarily. In particular,<br />

patients have a right to be informed of risks. Thus, patients may<br />

claim that, although consent was given, it was obtained negligently.<br />

Significant case law has arisen as a result of doctors failing to<br />

communicate adequately with their patients, either because there<br />

had been no proper consultation before treatment or because the<br />

doctor failed to disclose the risks inherent in the proposed<br />

treatment.<br />

The concept of informed consent is based on the moral principle<br />

of respect for autonomy, which leads to the patient having the<br />

right to know. 38 It is recognized throughout most Western legal<br />

systems. In the United Kingdom, Lord Templeman stated:<br />

“In order to make a balanced judgment, if he chooses to do so, the<br />

patient needs to be aware of the general dangers and of any special<br />

dangers in each case without exaggeration or concealment.” 39<br />

Similarly, in Germany it has been held that:<br />

“… as a principle the patient must know what he is consenting to.<br />

For him to acquire this position more is necessary than the<br />

disclosure that he needs an operation.” 40<br />

From an ethical point of view, informed consent has criteria<br />

which must be met before consent can be claimed to be truly<br />

“informed.” First of all, the patient must be of sound, competent<br />

mind. He or she must be undergoing the procedure voluntarily<br />

and not under coercion. They must be informed about what the<br />

procedure involves and any risks inherent therein. The more<br />

serious the risk or potential harm, the greater the degree of<br />

information required. Most importantly, they must be able to<br />

understand the explanation given to them by the doctor and<br />

finally, when all the above conditions are satisfied, the patient gives<br />

the doctor authority to proceed with treatment. 41<br />

Informed Consent in the<br />

Practice of Pediatrics<br />

The concept of informed consent is equally applicable to the<br />

practice of pediatrics. As discussed above, most courts throughout<br />

the world are prepared to accept that children of sufficient maturity<br />

and understanding—the so-called “mature” or “emancipated”<br />

minor—can consent to treatment. On the other hand, informed<br />

consent must be obtained from the parents or legal guardian of a<br />

child who is considered too immature to give his or her own<br />

consent. In such cases, based on the moral principle of respect for<br />

autonomy, the parents or legal guardian must be aware of the<br />

general risks of a procedure about to be undertaken. In either case,

2114 PART 6 ■ Specific Considerations<br />

if inadequate information was given, then the doctor may be held<br />

to be negligent. Thus, if inadequate information about risk is<br />

given, and the child suffers harm, then the parents may claim that<br />

the doctor is responsible because they never gave “informed<br />

consent” in the first place. The question therefore is how closely<br />

does the law match the ethical description of informed consent<br />

given above?<br />

The Different Legal Standards of Disclosure<br />

The reality is that different legal systems in different countries<br />

utilize different standards of disclosure. There are three different<br />

standards:<br />

The professional standard test is the standard of disclosure that<br />

the profession would be expected to tell the patient. Thus, based<br />

on the old English case of Bolam, 42 a doctor would not be guilty of<br />

negligence if he acted in accordance with a practice accepted as<br />

proper by a responsible body of medical opinion skilled in that<br />

particular art. The same test applies to the disclosure of risk. If a<br />

responsible body of medical opinion would not have disclosed<br />

what was omitted by the defendant the doctor would not be found<br />

guilty of negligence. Thus, even a significant minority of doctors<br />

in agreement will leave the plaintiff in difficulties.<br />

The patient standard, on the other hand, can be subdivided into<br />

two: a particular patient standard and a prudent patient standard,<br />

corresponding to subjective or objective standards. The particular<br />

patient (subjective) test defines what the actual patient would have<br />

done if notified of all relevant facts. This test suffers from the<br />

necessity of hindsight, and since the relevant facts only exist in the<br />

mind of the individual, an accusation is very hard to refute. It is,<br />

however, a desirable standard insofar as it embodies personal<br />

factors, including many that are nonmedical, which might affect<br />

a particular person’s decision. The prudent patient test requires<br />

the plaintiff to establish that a reasonable person would not have<br />

undergone a recommended procedure after having been advised<br />

of all significant risks. This also is problematic, as it is impossible<br />

to define what a reasonable person is, specific to each case.<br />

However, it appears fair to both sides in that a reasonable doctor<br />

and a reasonable patient are meeting on comparable terms. 43<br />

The Bolam test for medical negligence still carries significant<br />

weight in the United Kingdom. That is, “a doctor is not negligent<br />

if he acts in accordance with a practice accepted at the time as<br />

proper by a responsible body of medical opinion.” This ruling<br />

arose out of a case in 1957. Bolam, who consented to electroconvulsive<br />

treatment but suffered fractures in the course of the<br />

treatment (he was not given any muscle relaxants), argued that he<br />

had not been informed of the risks. The judge held that the<br />

amount of information given had accorded with generally<br />

accepted medical practice and the case was dismissed. The Bolam<br />

test corresponds to the professional medical standard test—that<br />

“the doctor knows best.” This accords with the principles of<br />

benevolence and nonmaleficence: “do good and do no harm.”<br />

The professional standard test has been attacked by many,<br />

including some judges in the United Kingdom such as Lord<br />

Scarman. Although he would permit the medical experts to<br />

establish the standard of care in relation to diagnosis and treatment,<br />

44 he found it unacceptable in relation to informed consent.<br />

He has commented that the legal standard is, in effect, set by the<br />

medical profession. If a doctor can show that his advice or his<br />

treatment reached a standard of care which was accepted by a<br />

respectable and responsible body of medical opinion as adequate,<br />

he cannot be made liable in damages if anything goes wrong. It is<br />

a totally medical preposition erected into a working rule of law. 45<br />

Since then, the Bolam test, with respect to information<br />

disclosure, has been modified following the case of Bolitho. 46 In<br />

this case, it was decided that a doctor is not negligent if he acts<br />

in accordance with a practice rightly accepted at the time as<br />

proper by a responsible body of medical opinion. The key word<br />

here is “rightly.” In effect, this allows a court to decide if the<br />

“responsible body of medical opinion” is correct. It transfers the<br />

final decision from the medical profession to the legal system.<br />

However, it still remains that the legal doctrine of informed<br />

consent in the United Kingdom is primarily a law of disclosure<br />

based on a general obligation to exercise reasonable care by giving<br />

information.<br />

Giesen in turn states: 47<br />

“The law in most jurisdictions seeks to ensure the full and consistent<br />

protection of the patient’s rights … this goal requires that<br />

objective and judicially determined standards of care be imposed<br />

upon doctors. In relation to consent to medical treatment the primary<br />

value of individual autonomy implies that the informational<br />

needs of the particular patient must determine the legal standard<br />

of disclosure. In so far as English judges have privileged the medical<br />

profession, above all others, by unquestioningly ratifying its<br />

practices in relation to treatment and disclosure, they may be said<br />

to have abandoned their constitutionally mandated tasks of adjudication<br />

and the development of law on an objective basis. This<br />

position is at odds with that in most other common law countries<br />

and is notably isolated within the context of the European<br />

Community.”<br />

In other parts of the world, the “patient-based materiality risk<br />

standard” is well established. In the United States, the landmark<br />

case of Canterbury v. Spence 48 and in Australia the case of Rogers<br />

v. Whitaker 49 imply that doctors must disclose any material risk<br />

about a procedure before informed consent has been given. The<br />

important concept here is an understanding of the meaning of the<br />

word “material.” It implies that, provided knowledge of a particular<br />

risk will be important to the decision making process of the<br />

patient, then such a risk needs to be disclosed, irrespective of<br />

the likelihood of it occurring. This could mean anything from the<br />

simplest to the most life-threatening complication. The issue is<br />

how much importance the patient attaches to the risk of the<br />

complication occurring.<br />

RESEARCH IN CHILDREN<br />

Overview and General Considerations<br />

The issue of undertaking research in children raises many legal<br />

and ethical dilemmas. Apart from the fact that they are vulnerable<br />

to being used to further adult interests, questions such as what<br />

level of maturity is required to consent to a research proposal still<br />

arise. Furthermore, harm, pain, and distress may arise out of any<br />

research, including such simple procedures as taking blood<br />

samples.<br />

Research can conveniently be divided into therapeutic and<br />

nontherapeutic, although in many cases it may be difficult to<br />

differentiate the two. In therapeutic research it is probable (or<br />

at least the aim should be) that the research will directly benefit<br />

the patient. Nontherapeutic research, on the other hand, will<br />

not benefit that particular patient, although the results may be

CHAPTER <strong>128</strong> ■ Consent, Research, and Withdrawing Treatment 2115<br />

very useful in benefiting future patients. It serves as a learning<br />

mechanism for future patients.<br />

Therapeutic Research<br />

The question of minors being involved in therapeutic research is<br />

not too controversial and many of the ethical conditions applicable<br />

to adult research apply. Thus, the research doctor has a duty to act<br />

in the best interests of his research patient and not to harm him.<br />

It has been held in the United States 50 and in Germany 51 that it is<br />

legally wrong for a doctor to withhold information about experimental<br />

therapy for fear that the patient may refuse that therapy,<br />

even though the doctor believes it is in the patient’s best interest to<br />

receive it.<br />

The issue has been clarified somewhat in the European<br />

Community by the 2001 EC Directive, 52 now also part of U.K.<br />

Law, 53 where four fundamental principles are outlined regarding<br />

research in relation to a minor. These are: the requirement of<br />

informed consent by a person with parental responsibility or a<br />

legal representative; the clinical trial has been designed to<br />

minimize pain, discomfort, fear, and any other foreseeable risk;<br />

the risks and degree of distress have been specifically defined; and<br />

that the interests of the patient always prevail over those of science<br />

and society.<br />

The mature minor concept discussed earlier confuses the issue<br />

slightly. It would appear from the previous discussion that a child<br />

who is old enough to understand the risks and implications of an<br />

experimental therapy should be ethically and legally entitled to<br />

consent. It must be pointed out, however, that this application<br />

within the context of research has never been tested in a U.K. court<br />

of law. In France, minors who have been emancipated, either by<br />

marriage or, when they are older than 16 years, by decision of their<br />

parents, should be regarded as adults. The role of parent or<br />

guardian should in such cases be essentially a confirmatory one. It<br />

might be reasonable for a parent or guardian to override a child’s<br />

willingness to take part in research which the adult believes to be<br />

against the child’s interests. There should be no corresponding<br />

opportunity for the parent or guardian to override the capable<br />

child’s refusal. 54<br />

Concerning immature minors, parents must give voluntary<br />

consent, fully understanding the risks and benefits of the research<br />

proposed. After assessing this risk benefit ratio, they must believe<br />

that it is in the minor’s best interest to be involved in that study.<br />

They can then consent on behalf of the minor. The Declaration of<br />

Helsinki 55 states that the consent of the legal guardian should be<br />

procured on behalf of the “legally incompetent.” In U.K. law, the<br />

Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004<br />

requires a similar approach: “Informed consent given by a person<br />

with parental responsibility or a legal representative … shall<br />

represent the minor’s presumed will.” 56<br />

However, who is actually entitled to consent varies between<br />

jurisdictions.<br />

In France, under article L209-9 of the Public Health Code,<br />

participation requires the consent of the persons legally<br />

responsible for the child. The persons responsible in turn are<br />

regulated by article 371-2 of the Civil Code, parental authority<br />

belonging to both mother and father of the child. However, the<br />

implementation of this is complicated by considerations of<br />

whether the family is united or not. Further complications arise if<br />

the parents disagree.<br />

In the United Kingdom, consent by one parent is sufficient as<br />

parents may act independently, unless a court order has been<br />

made restricting his or her right to consent. 57 However, as Lord<br />

Donaldson stated,<br />

“If the parents disagree, one consenting and the other refusing, the<br />

doctor will be presented with a professional and ethical, but not<br />

with a legal problem because, if he has the consent of one<br />

authorized person, treatment will not without more constitute a<br />

trespass or criminal assault.” 58<br />

Nontherapeutic Research<br />

The question of nontherapeutic research (i.e., research that will<br />

not directly treat the patient, although the results may benefit<br />

other patients), is much more controversial, and issues relating to<br />

consent are pivotal. The primary concern must be with the welfare<br />

of the child, and, although parents are given legal authority to<br />

consent on behalf of their children, this power cannot be used to<br />

place the child at risk of harm. By definition, a child does not gain<br />

directly by being involved in nontherapeutic research and indeed<br />

may be harmed. This implies that parents cannot consent to their<br />

children being involved in nontherapeutic research. In the United<br />

Kingdom, the Medical Research Council stated that:<br />

“in the strict view of the law, parents and guardians of minors<br />

cannot give consent on their behalf to any procedures which are of<br />

no particular benefit to them and which might carry some risk of<br />

harm.” 59<br />

Thus, it has been suggested that it appears to be extremely<br />

doubtful whether valid consent in nontherapeutic research can be<br />

given on behalf of their children, because it cannot be in the child’s<br />

best interests. 60<br />

There are counterarguments to all of this. Firstly, there are no<br />

specific legal rules or rulings on which to base this view. 61 From an<br />

ethical point of view, it is claimed that in everyday life society<br />

allows parents a certain amount of discretion when subjecting<br />

their offspring to risks. 62 Thus, the “reasonable parent test”<br />

employed by Lord Reid in S v. S (1970) 63 could be used to support<br />

the view that reasonable parents may be allowed to subject their<br />

children to certain types of nontherapeutic research, especially<br />

where the risk–benefit ratio is highly in favor of large potential<br />

benefits to others. Furthermore, many believe that the test should<br />

be whether the parents are “clearly not acting against the best<br />

interests of the child.”<br />

The extreme arguments either advocating no research at all or<br />

justifying it as a duty to society are not acceptable. The middleof-the-road<br />

attitude of balancing the risks to the child with the<br />

many advantages to society as a whole should prevail. If risks are<br />

significant, research should not be allowed, because this would be<br />

clearly acting against the best interests of the child.<br />

The Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health has stated<br />

that it would be unethical to submit a child to more than minimal<br />

risk when the procedure offers no benefit to them. They define<br />

“minimal” as procedures such as questioning, observing, and<br />

measuring children, provided that procedures are carried out in a<br />

sensitive way, and that consent has been given. Procedures with<br />

minimal risk include collecting a single urine sample (but not by<br />

aspiration), or using blood from a sample that has been taken as<br />

part of treatment. 64 The Institute of Medical Ethics, in turn,<br />

defined “minimal” as a risk of death lower than 1:1,000,000, a risk

2116 PART 6 ■ Specific Considerations<br />

of major complications less than 1:100,000 and a risk of minor<br />

complications of less than 1:1,000. 65 It is to be noted that taking a<br />

sample of blood from a vein purely for research purposes is<br />

considered to be low risk rather than a minimal risk. It should also<br />

be noted that in all cases, when parental consent is obtained, the<br />

agreement of school-age children should also be requested by the<br />

researchers. Regardless of age, a child’s refusal to participate in<br />

nontherapeutic research should always be respected, and indeed<br />

where a child becomes upset by a procedure, this should be<br />

accepted as a valid refusal. 66<br />

The concept of the mature minor giving valid consent for<br />

diagnostic or therapeutic interventions has been discussed above<br />

and is widely accepted. It is, however, not certain that this would<br />

apply to nontherapeutic research or experimentation. A practical<br />

approach to this issue would be to obtain parental consent for all<br />

minors, regardless of maturity.<br />

Mature minors, by definition, should be allowed to decide for<br />

themselves in the same way that adults are allowed, with one<br />

limitation: that the greater the risk to the child, the older he or she<br />

must be before a doctor decides he or she is “mature.”<br />

LETTING CHILDREN DIE<br />

It would be impossible to give a full account of the ethics regarding<br />

controversies about withholding and withdrawing treatment in<br />

the limited space available. The Royal College of Pediatrics and<br />

Child Health in the United Kingdom, 67 however, has issued guidelines<br />

on how to approach such decisions and a summary is<br />

provided here.<br />

There are five situations where withholding or withdrawing of<br />

curative medical treatment might be considered:<br />

1. The brain dead child. In the older child, where criteria of brainstem<br />

death are agreed by two practitioners in the usual way, it<br />

may still be technically feasible to provide basic cardiorespiratory<br />

support by means of ventilation and intensive care. It is<br />

agreed within the profession that treatment in such circumstances<br />

is futile and withdrawal of current medical treatment is<br />

appropriate. It is interesting to note that brain-stem death<br />

criteria have no legal basis. In other words, the concept is<br />

accepted by the medical profession and, in turn, the law accepts<br />

the profession’s view that the patient is legally dead.<br />

2. The permanent vegetative state. The child who develops a<br />

permanent vegetative state following insults such as trauma or<br />

hypoxia is reliant on others for all care and does not react or<br />

relate with the outside world. It may be appropriate both to<br />

withdraw current therapy and to withhold further curative<br />

treatment. It must be noted that in these cases the law in most<br />

countries wishes to be involved in the decision-making process<br />

of withdrawing treatment.<br />

3. The “no chance” situation. The child has such severe disease<br />

that life-sustaining treatment simply delays death without any<br />

significant alleviation of suffering. Medical treatment in this<br />

situation may thus be deemed inappropriate.<br />

4. The “no purpose” situation. Although the patient may be able<br />

to survive with treatment, the degree of physical or mental<br />

impairment will be so great that it is unreasonable to expect<br />

them to bear it. The child in this situation will never be capable<br />

of taking part in decisions regarding treatment or its<br />

withdrawal.<br />

5. The “unbearable” situation. The child and/or family feel that in<br />

the face of progressive and irreversible illness further treatment<br />

is more than can be borne. They wish to have a particular<br />

treatment withdrawn or to refuse further treatment irrespective<br />

of the medical opinion on its potential benefit. Oncology<br />

patients who are offered further aggressive treatment might be<br />

included in this category. The assessment of competence of the<br />

child referred to above would once again apply.<br />

In situations that do not fit any of these five categories, or where<br />

there is dissent or uncertainty about the degree of future<br />

impairment, the child’s life should always be safeguarded by all in<br />

the health care team in the best possible way. Clearly, the<br />

recognition that the management of any patient is undertaken not<br />

by medical staff acting on their own, but by a health care team that<br />

also involves nurses, physiotherapists, social workers, and so on<br />

means that a team approach that fully integrates the wishes of the<br />

child and family is essential.<br />

Decisions must never be rushed and must always be made by<br />

the team with all evidence available. In emergencies, it is often<br />

doctors in training who are called to resuscitate. Rigid rules, even<br />

for conditions which seem hopeless, should be avoided; lifesustaining<br />

treatment should be administered and continued until<br />

a senior and more experienced doctor arrives.<br />

The decision to withhold or withdraw curative therapy should<br />

always be followed by consideration of the child’s palliative or<br />

terminal care needs. These may be related to symptom alleviation<br />

(e.g., analgesia or anticonvulsant therapy) or may be related to<br />

dignified and comforting nursing care.<br />

FETAL RIGHTS<br />

This chapter would not be complete without mentioning briefly<br />

the rights of the fetus. It must be pointed out that the law in many<br />

respects is either poorly developed or contradictory. Furthermore,<br />

recognition of fetal rights may result in conflict with those of the<br />

mother. In particular, support or failure to recognise fetal rights is<br />

usually dependant on one’s views on abortion.<br />

Much opposition to legal abortion in the West is claimed to be<br />

based on a concern for fetal rights. Some laws attempt to establish<br />

the right to life of the fetus from the moment of fertilization and<br />

regard the fetus as a person with equal legal status to that of any<br />

other human. The 1978 American Convention on Human Rights<br />

Article 4.1 states that “Every person has the right to have his life<br />

respected. This right shall be protected by law and, in general,<br />

from the moment of conception.” Similarly, the Eighth Amendment<br />

of the Constitution of Ireland recognizes “the right to life of<br />

the unborn” whereas the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany<br />

in 1993 held that the constitution guaranteed the right to life from<br />

conception.<br />

On the other hand, many prochoice groups oppose fetal rights<br />

even when they do not impinge directly on the abortion issue,<br />

because they perceive this as a slippery slope strategy to restricting<br />

abortions. 68 Such groups work to protect and advance reproductive<br />

liberty, including the rights of all women to decide whether<br />

and when to have children, to use contraception, and to safeguard<br />

their own health. In their view, the woman’s health is paramount<br />

and any decision concerning her medical care—including any<br />

decision to continue or terminate her pregnancy—is based solely<br />

on her best interests.

CHAPTER <strong>128</strong> ■ Consent, Research, and Withdrawing Treatment 2117<br />

A number of countries have enacted laws to enable the<br />

protection or even simple recognition of the fetus. Recognition<br />

may be granted under specific conditions, such as being a victim<br />

of crime, a beneficiary of insurance, or as an inheritor of property.<br />

For example, the Unborn Victims of Violence Act is a United<br />

States law passed in 2004 that defines violent assault committed<br />

against pregnant women as being a crime against two persons: the<br />

woman and the fetus she is carrying. 69<br />

There have also been a number of initiatives which discourage<br />

women from engaging in certain behaviors deemed to be detrimental<br />

to the health or development of the fetus. The most<br />

obvious of these are the misuse of alcohol or tobacco. For example,<br />

there is evidence that the use of tobacco products or exposure to<br />

secondhand smoke during pregnancy is linked to low birthweight,<br />

70 whereas many countries encourage those who are pregnant<br />

to avoid alcohol. However, it is still unclear whether society<br />

has a moral right to police and control the behavior of pregnant<br />

women. If it is felt that it does, what will limit those controls? More<br />

worryingly, such a course of action may lead to pregnant women<br />

either avoiding prenatal care or withholding information, both of<br />

which may actually lead to even more harm befalling the fetus.<br />

On the other hand, society has a duty to protect the future child<br />

and this right to be born healthy needs to be balanced against<br />

a pregnant woman’s right to freedom of choice and control over<br />

her own life.<br />

Although no U.S. state has enacted laws which criminalize<br />

specific behavior during pregnancy, many women have been<br />

criminally prosecuted or arrested under existing child abuse<br />

statutes for allegedly bringing about harm in utero through their<br />

conduct during pregnancy. 71 It must be stressed that many of these<br />

convictions have been overturned on appeal.<br />

A different form of fetal rights protection has arisen because of<br />

cultural preferences for male children. Some countries have passed<br />

laws restricting the practice of abortion based upon the gender of<br />

the fetus. India banned the practice of abortion for reasons of fetal<br />

sex in 2002 and China in 2003.<br />

On the other hand, some governments have enacted laws stating<br />

that fetuses are not legally recognized persons. The Canadian<br />

Criminal Code, section 223, states that a fetus is a “human being …<br />

when it has completely proceeded, in a living state, from the body<br />

of its mother whether or not it has completely breathed, it has an<br />

independent circulation or the navel string is severed.”<br />

Similarly, in the case of Vo v. France (European Court of Human<br />

Rights/France) it was argued that the European Convention for the<br />

Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms did not<br />

protect the rights of an unborn fetus and that recognizing an<br />

unborn fetus’s right to life would threaten women’s human rights by<br />

permitting a government to privilege the rights of a fetus over those<br />

of a pregnant woman. Furthermore, if upheld, it would have<br />

rendered the abortion laws of most member countries invalid<br />

under Article 2. The European Court of Human Rights agreed and<br />

in July 2004 issued a decision in which it declined to recognize a<br />

fetus as a person under the European Convention.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Ethical and legal issues pertaining to pediatrics are complicated<br />

by the special vulnerability of the subjects. The competence of<br />

children and the legality of their consent also create uncertainty.<br />

Religious beliefs and social demands merely serve to confuse<br />

further. It remains very difficult to give precise answers to many of<br />

the questions that pediatric anesthesiologists would like answered.<br />

Frequently, the introductory statement in many arguments is “the<br />

legal position seems to be …” The uncertainties of the law, compounded<br />

by the fact that different countries have unique legal<br />

systems and interpret ethical issues differently, does not help. Also,<br />

ethical beliefs change with time. What is currently thought ethical<br />

was not necessarily so a few years ago, and vice versa. The law<br />

tends to change even more slowly and takes time to catch up with<br />

current ethical thinking. The answers to many issues are therefore<br />

constantly changing. It is hoped that, in the future, the European<br />

Community may analyze the various issues involved and issue<br />

guidelines to ensure the safety and protection that children deserve.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

1. British Medical Association. Medical Ethics Today: The BMA’s Handbook<br />

of Ethics and Law. 2nd ed. London: BMJ Books; 2004. p. 72.<br />

2. Skegg PDG. Law, Ethics and Medicine. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1984.<br />

3. Schloendorff ME. Appellant v. The Society of the New York Hospital,<br />

Respondent. Court of Appeals of New York 211 N.Y. 1914; 125; 105 N.E. 92.<br />

4. Mason JK, Laurie GT. Biomedical human research and experimentation.<br />

In: Mason JK, McCall-Smith RA, editors. Law and Medical Ethics. 7th ed.<br />

New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 353–354.<br />

5. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 12.<br />

November 20, 1989.<br />

6. Johnston v. Wellesley Hospital (1971). 2 OR 103, (1970) 17. Dominion<br />

Legal Rep (DLR 3d) 139 (Ont. H.C.).<br />

7. Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Metropolitan Toronto v. K. (Ontario<br />

District Court). Rep Fam Law (RFL 2d). 1985;47:361.<br />

8. Gillick v. West Norfolk AHA (1984). 1 All England Rev 365 (1985); 3 All<br />

England Rev 402, HL.<br />

9. Lord Browne-Wilkinson (1997). 4 All England Rev 771 at 779. Butterworth’s<br />

Med Law Rev (BMLR). 1998;39:1–10.<br />

10. Giesen D. International Medical Malpractice Law: A Comparative Study<br />

of Civil Responsibility Arising From Medical Care. Tübingen: JCB Mohr<br />

Siebeck Verlag; 1988. p. 940.<br />

11. British Medical Association. Medical Ethics Today: The BMA’s Handbook<br />

of Ethics and Law. 2nd ed. London: BMJ Books; 2004. p. 135.<br />

12. General Medical Council. 0–18 years: guidance for all doctors. In:<br />

Regulating Doctors and Ensuring Good Medical Practice. General Medical<br />

Council; 2007. p. 52. Available at: http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/<br />

children_and_young_people.asp. Accessed September 22, 2010.<br />

13. Hoggett B. Parents, children and medical treatment: the legal issues. In:<br />

Rights and Wrongs in Medicine. Byrne P, editor. London: King’s Fund; 1986.<br />

pp. 163–175.<br />

14. Douglas G. The retreat from Gillick. Modern Law Rev. 1992;55:569–573.<br />

15. Re R (a minor) (wardship: medical treatment) Fam11. Butterworth’s Med<br />

Law Rev (BMLR) Canada. 1992;7:147.<br />

16. Re W (a minor) (medical treatment) (4 All England Rev 627). Butterworth’s<br />

Med Law Rev (BMLR). 1992;9:22.<br />

17. Re M (child: refusal of medical treatment) Federal Legal Reports (2 FLR<br />

1097). Butterworth’s Med Law Rev (BMLR). 2000;52:124.<br />

18. Mason JK, Laurie GT. Consent to treatment. In: Mason JK, McCall-Smith<br />

RA, editors. Law and Medical Ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University<br />

Press; 2006. p. 372.<br />

19. Montgomery J. Health Care Law. New York: Oxford University Press;<br />

1997. p. 286.<br />

20. Northern Ireland. Houston (applicant). Butterworth’s Med Law Rev (32<br />

BMLR 93) 1996. Children (Scotland) Act 1995 s15(5)(b). Summarized in:<br />

British Medical Association, Ethics Department. Medical Ethics Today:<br />

The BMA’s Handbook of Ethics and Law. 2nd ed. London: BMJ Books;<br />

2004. p. 143.<br />

21. Mason JK, Laurie GT. In: Mason and McCall-Smith’s Law and Medical<br />

Ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 223.<br />

22. Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Management of<br />

Anaesthesia for Jehovah’s Witnesses. 2nd ed. London: AAGBI; 2005. p. 9.<br />

Available at: http://www.aagbi.org/publications/guidelines/docs/jehovah.<br />

pdf. Accessed September 22, 2010.<br />

23. Re: T. All England Law Rep. 1992;4:647–670.<br />

24. Couture-Jacquet v. Montreal Children’s Hospital. Dominion Legal Rep<br />

(DLR 4th) (Quebec). 1986;28:22.

2118 PART 6 ■ Specific Considerations<br />

25. The Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 (England). Local Authority<br />

Social Services Letter (LASSL) 2004. 4. Available at: http://www.<br />

dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Localauthorit<br />

ysocialservicesletters/AllLASSLs/DH_4074779. Accessed September 22,<br />

2010.<br />

26. Brazier M. The practice of medicine today. In: Brazier M, Cave E, editors.<br />

Medicine, Patients and the Law. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books; 1992:<br />

10:73–93.<br />

27. Williams N, Kapila L. Complications of circumcision. Brit J Surg. 1993;80:<br />

1231–1236.<br />

28. Management of Foreskin Conditions and Male Circumcision. Statement<br />

from the British Association of Paediatric Urologists, the Royal College of<br />

Nursing, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, the Royal<br />

College of Surgeons of England and the Royal College of Anaesthetists.<br />

2007. Available at: http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/media/medianews/statement<br />

onmalecircumcision. Accessed September 22, 2010.<br />

29. Wheeler R. Gillick or Fraser? A plea for consistency over competence in<br />

children. Brit Med J. 2006;8:807–812.<br />

30. Dwyer JG. Parents’ religion and children’s welfare: debunking the doctrine<br />

of parents’ rights. Calif Law Rev. 1994;82:1371–1447.<br />

31. Re J (a minor) (prohibited steps order: circumcision), sub nom Re J<br />

(child’s religious upbringing and circumcision) and Re J (specific issue<br />

orders, Muslim upbringing and circumcision). Federal Legal Rep (1 FLR<br />

571) 2000 and Federal Court Rep (1 FCR 307) 2000. Butterworth’s Med<br />

Law Rev (BMLR). 2000;52:82–96.<br />

32. Re S (children) (specific issue: circumcision). Federal Legal Rep (FLR).<br />

2005;1:236.<br />

33. Simms v Simms. Weekly Law Rep (WLR). 2003;2:1465 and All England<br />

Law Rep (All ER). 2003;1:669.<br />

34. Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental<br />

Freedoms (CETS 005). The European Convention on Human Rights.<br />

Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe. Rome (4.IX.1950, TS 71; Cmnd<br />

8969). Human Rights Act 1988. Available at: http://conventions.coe.<br />

int/treaty/Commun/QueVoulezVous.asp?NT=005&CL=ENG. Accessed<br />

September 22, 2010.<br />

35. The law and ethics of male circumcision—guidance for doctors. British<br />

Medical Association. Available at: http://www.cirp.org/library/statements/<br />

bma2003/. Accessed September 22, 2010.<br />

36. Human Tissue Act 2004. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Available at:<br />

http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2004/pdf/ukpga_20040030_en.pdf.<br />

Accessed: April 21, 2010.<br />

37. Council of Europe. The European Convention on Human Rights and<br />

Biomedicine. Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights<br />

and Biomedicine. On Transplantation of Organs and Tissues of Human<br />

Origin. 2002; Article 14. 2008. Strasbourg, France: European Union.<br />

Available at: http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/EN/Treaties/Html/186.<br />

htm. Accessed: April 21, 2010.<br />

38. McLean SAM. A patient’s right to know. In: Legal Issues in Medicine.<br />

Aldershot: Gower/Darmouth Publishing; 1989. pp. 93–113.<br />

39. Sidaway v. Bethlem Royal Hospital Governors. All England Law Rep (All<br />

ER). 1985;1:643 HL.<br />

40. Bovine Growth Hormone. 21 September 1982 (VI ZR 302/80) VersR 1982<br />

(1193–1194).<br />

41. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Bioethics. 4th ed. New York:<br />

Oxford University Press; 1994. p. 270.<br />

42. Bolam v Friern. Hospital Management Committee. All England Law Rep<br />

(2 All ER 118) 1957 and Weekly Law Rep (1 WLR 582) 1957.<br />

43. Mason K. Consent to treatment and research in the ICU. In: Ethics and the<br />

Law in Intensive Care. Pace NA, McLean SAM, editors. New York: Oxford<br />

University Press; 1997. p. 38.<br />

44. Maynard v. West Midlands Regional Health Authority. All England Law<br />

Rep (1 All ER 635). 1985.<br />

45. Scarman L. Law and medical practice. In: Byrne P, editor. Medicine in<br />

Contemporary Society. London: King Edward’s Hospital Fund for London;<br />

1987. p. 134.<br />

46. Bolitho v. City and Hackney Health Authority. All England Law Rep<br />

(4 All ER 771). 1997.<br />

47. Giesen D. The patient’s right to know—a comparative law perspective.<br />

Med Law. 1993;12:553–565.<br />

48. Canterbury v. Spence (1972). 464 F2d 772 (DC Cir 1972).<br />

49. Rogers v. Whittaker (HC Australia). Med Law Rev (4 Med LR 79) 1993<br />

50. Edgars J, Morton NS, Pace NA. Review of ethics in paediatric anaesthesia:<br />

consent issues. Paed Anaesth. 2001;11;355–71.<br />

51. Bovine Growth Hormone. (1984) 7 Feb 1984 (VI ZR 174/82) BGHZ 90,<br />

103 (107–108, 111).<br />

52. European Parliament and of the Council of Europe. Directive 2001/20/EC<br />

on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative<br />

provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good<br />

clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products<br />