Weather and Climate Extremes in a Changing Climate. Regions of ...

Weather and Climate Extremes in a Changing Climate. Regions of ...

Weather and Climate Extremes in a Changing Climate. Regions of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

The U.S. <strong>Climate</strong> Change Science Program Chapter 1<br />

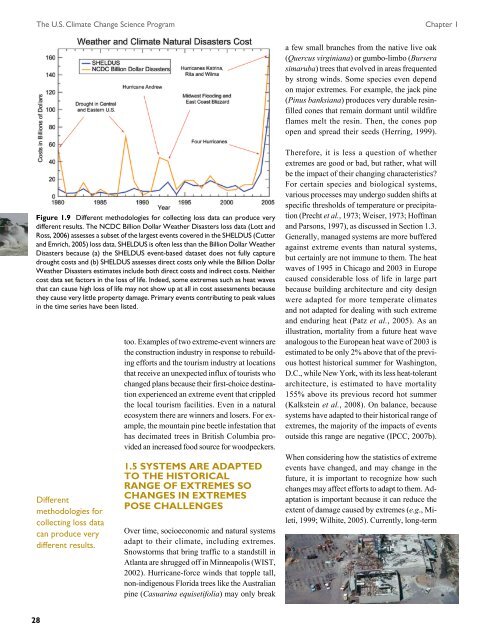

Figure 1.9 Different methodologies for collect<strong>in</strong>g loss data can produce very<br />

different results. The NCDC Billion Dollar <strong>Weather</strong> Disasters loss data (Lott <strong>and</strong><br />

Ross, 2006) assesses a subset <strong>of</strong> the largest events covered <strong>in</strong> the SHELDUS (Cutter<br />

<strong>and</strong> Emrich, 2005) loss data. SHELDUS is <strong>of</strong>ten less than the Billion Dollar <strong>Weather</strong><br />

Disasters because (a) the SHELDUS event-based dataset does not fully capture<br />

drought costs <strong>and</strong> (b) SHELDUS assesses direct costs only while the Billion Dollar<br />

<strong>Weather</strong> Disasters estimates <strong>in</strong>clude both direct costs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>direct costs. Neither<br />

cost data set factors <strong>in</strong> the loss <strong>of</strong> life. Indeed, some extremes such as heat waves<br />

that can cause high loss <strong>of</strong> life may not show up at all <strong>in</strong> cost assessments because<br />

they cause very little property damage. Primary events contribut<strong>in</strong>g to peak values<br />

<strong>in</strong> the time series have been listed.<br />

Different<br />

methodologies for<br />

collect<strong>in</strong>g loss data<br />

can produce very<br />

different results.<br />

28<br />

too. Examples <strong>of</strong> two extreme-event w<strong>in</strong>ners are<br />

the construction <strong>in</strong>dustry <strong>in</strong> response to rebuild<strong>in</strong>g<br />

efforts <strong>and</strong> the tourism <strong>in</strong>dustry at locations<br />

that receive an unexpected <strong>in</strong>flux <strong>of</strong> tourists who<br />

changed plans because their first-choice dest<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

experienced an extreme event that crippled<br />

the local tourism facilities. Even <strong>in</strong> a natural<br />

ecosystem there are w<strong>in</strong>ners <strong>and</strong> losers. For example,<br />

the mounta<strong>in</strong> p<strong>in</strong>e beetle <strong>in</strong>festation that<br />

has decimated trees <strong>in</strong> British Columbia provided<br />

an <strong>in</strong>creased food source for woodpeckers.<br />

1.5 SyStEMS ARE AdAPtEd<br />

TO ThE hISTORICAl<br />

RANGE OF EXtREMES SO<br />

ChANgES IN ExTREMES<br />

POSE CHALLENGES<br />

Over time, socioeconomic <strong>and</strong> natural systems<br />

adapt to their climate, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g extremes.<br />

Snowstorms that br<strong>in</strong>g traffic to a st<strong>and</strong>still <strong>in</strong><br />

Atlanta are shrugged <strong>of</strong>f <strong>in</strong> M<strong>in</strong>neapolis (WIST,<br />

2002). Hurricane-force w<strong>in</strong>ds that topple tall,<br />

non-<strong>in</strong>digenous Florida trees like the Australian<br />

p<strong>in</strong>e (Casuar<strong>in</strong>a equisetifolia) may only break<br />

a few small branches from the native live oak<br />

(Quercus virg<strong>in</strong>iana) or gumbo-limbo (Bursera<br />

simaruba) trees that evolved <strong>in</strong> areas frequented<br />

by strong w<strong>in</strong>ds. Some species even depend<br />

on major extremes. For example, the jack p<strong>in</strong>e<br />

(P<strong>in</strong>us banksiana) produces very durable res<strong>in</strong>filled<br />

cones that rema<strong>in</strong> dormant until wildfire<br />

flames melt the res<strong>in</strong>. Then, the cones pop<br />

open <strong>and</strong> spread their seeds (Herr<strong>in</strong>g, 1999).<br />

Therefore, it is less a question <strong>of</strong> whether<br />

extremes are good or bad, but rather, what will<br />

be the impact <strong>of</strong> their chang<strong>in</strong>g characteristics?<br />

For certa<strong>in</strong> species <strong>and</strong> biological systems,<br />

various processes may undergo sudden shifts at<br />

specific thresholds <strong>of</strong> temperature or precipitation<br />

(Precht et al., 1973; Weiser, 1973; H<strong>of</strong>fman<br />

<strong>and</strong> Parsons, 1997), as discussed <strong>in</strong> Section 1.3.<br />

Generally, managed systems are more buffered<br />

aga<strong>in</strong>st extreme events than natural systems,<br />

but certa<strong>in</strong>ly are not immune to them. The heat<br />

waves <strong>of</strong> 1995 <strong>in</strong> Chicago <strong>and</strong> 2003 <strong>in</strong> Europe<br />

caused considerable loss <strong>of</strong> life <strong>in</strong> large part<br />

because build<strong>in</strong>g architecture <strong>and</strong> city design<br />

were adapted for more temperate climates<br />

<strong>and</strong> not adapted for deal<strong>in</strong>g with such extreme<br />

<strong>and</strong> endur<strong>in</strong>g heat (Patz et al., 2005). As an<br />

illustration, mortality from a future heat wave<br />

analogous to the European heat wave <strong>of</strong> 2003 is<br />

estimated to be only 2% above that <strong>of</strong> the previous<br />

hottest historical summer for Wash<strong>in</strong>gton,<br />

D.C., while New York, with its less heat-tolerant<br />

architecture, is estimated to have mortality<br />

155% above its previous record hot summer<br />

(Kalkste<strong>in</strong> et al., 2008). On balance, because<br />

systems have adapted to their historical range <strong>of</strong><br />

extremes, the majority <strong>of</strong> the impacts <strong>of</strong> events<br />

outside this range are negative (IPCC, 2007b).<br />

When consider<strong>in</strong>g how the statistics <strong>of</strong> extreme<br />

events have changed, <strong>and</strong> may change <strong>in</strong> the<br />

future, it is important to recognize how such<br />

changes may affect efforts to adapt to them. Adaptation<br />

is important because it can reduce the<br />

extent <strong>of</strong> damage caused by extremes (e.g., Mileti,<br />

1999; Wilhite, 2005). Currently, long-term