WEALTH

2c0esX1

2c0esX1

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

MACRO<br />

García-Herrero has one of those CVs that make<br />

you feel you’ve wasted your life. In addition to<br />

her day job, she serves as senior research fellow<br />

at the European think tank BRUEGEL, nonresident<br />

fellow at Cornell’s emerging market<br />

research center, and is adjunct professor at<br />

City University, Hong Kong. Among her other<br />

credits, she has had stints as chief economist<br />

for Emerging Markets at Banco Bilbao Vizcaya<br />

Argentaria (BBVA), at the Bank of International<br />

Settlements (BIS), and as a member of the<br />

Counsel to the Executive Board of the European<br />

Central Bank, as well as at the International<br />

Monetary Fund.<br />

THE SKY IS NOT FALLING<br />

For her, it is inevitable – barring massive social<br />

unrest or war – that China will not only double<br />

its economy by 2020 (over 2010 and in line with<br />

Beijing’s ambitious goals), but that it will again<br />

double it by 2050. This is despite the country’s<br />

posting in 2015 its worst GDP growth (6.9%) in<br />

25 years. But then she has little time for<br />

Chicken Little hedge funds in London or New<br />

York. The simplified market equation that<br />

assesses Chinese growth of xx.x% (insert your<br />

preferred number) as resulting in either<br />

economic stability or chaos, dodges the hard<br />

work and time required to analyze the<br />

complexities of modern China.<br />

“Deeper scrutiny shows Chinese policies<br />

can preserve economic stability in the<br />

transformation to a more sustainable economic<br />

growth model,” she explains. “But that doesn’t<br />

mean it’s all rosy, because the way China<br />

has doubled its income in the past is no<br />

longer available.”<br />

The way she sees it is that 2016 will be<br />

crucial for China. The country is shifting<br />

growth away from investment to consumption,<br />

and its industrial base from basic manufacturing<br />

to a medium-high technology level. But this is<br />

occurring at a time when one of the engines of<br />

growth, urbanization, is losing strength.<br />

Over the past three decades, China<br />

witnessed the biggest movement of humanity<br />

seen in such a short period. More than 500<br />

million people left the countryside; China’s<br />

cities, now home to more than half the<br />

country’s 1.35 billion people, are still growing<br />

by the population of Belgium (11.3 million)<br />

every year. However, this movement is slowing: roughly 70% of those that<br />

will move have done so already. While 300–400 million may still shift,<br />

the structural growth provided by urbanization is weakening.<br />

“What we can expect for the next five years for China is cloudier than<br />

what we have seen in the last five,” she reflects. Growth in China will be<br />

slower, and rightly so, because that is the price that must be paid for<br />

higher consumption ratios. As policy makers try to rebalance demand,<br />

they cannot afford to reproduce the high growth rates of the past<br />

because of an aversion to inflation.<br />

OUT TO 2050<br />

On a purchasing power parity basis, China is already the world’s largest<br />

economy (at $19.92 trillion) and García-Herrero doesn’t expect this to<br />

change. By 2050, she believes China will be far richer, that it will still be<br />

the largest economy, but that it will also be extremely old. “China will<br />

age dramatically,” she notes. “The labor force will decrease rapidly from<br />

2016 onwards. From then on, more people will retire than enter the<br />

workforce. By 2040, its population is projected to be 1.4 billion and China<br />

will have 420 million over the age of 60, the majority of them retired.”<br />

Such adverse demographics (see pages 52–53) will reduce potential<br />

growth, she argues. As today’s older workers retire, and society finds too<br />

few younger ones to replace them, this will commence a vicious circle of<br />

rising wages, declining demand and deteriorating saving rates that will<br />

also bring potential growth down.<br />

Whether the economic power that China accumulates by then will<br />

be enough to fund its growing pension and healthcare costs is an open<br />

question and one that the country is scrambling now to address. With<br />

China unlikely to be still running a currency surplus, García-Herrero<br />

believes it will be forced to borrow abroad to support its dependents,<br />

which it should do easily as the renminbi will be firmly established as<br />

an international currency.<br />

But then, as she willingly concedes, pundits such as herself have<br />

been wrong in the past even on their short-term calls. China is just that<br />

sort of place.<br />

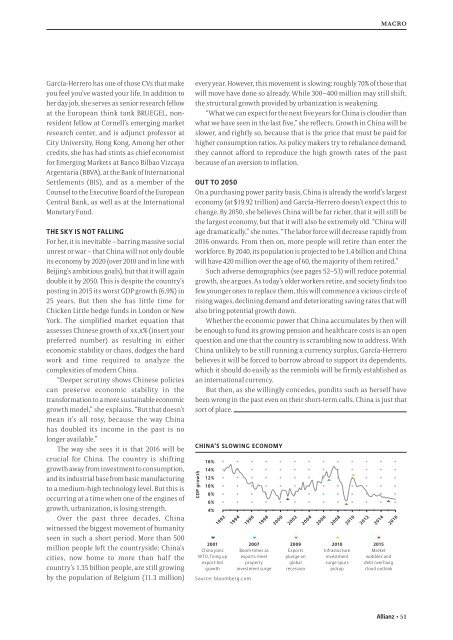

CHINA’S SLOWING ECONOMY<br />

GDP growth<br />

16%<br />

14%<br />

12%<br />

10%<br />

8%<br />

6%<br />

4%<br />

1992<br />

2001<br />

China joins<br />

WTO, firing up<br />

export-led<br />

growth<br />

1994<br />

1996<br />

Source: bloomberg.com<br />

1998<br />

2007<br />

Boom times as<br />

exports meet<br />

property<br />

investment surge<br />

20 0 0<br />

20 02<br />

2009<br />

Exports<br />

plunge on<br />

global<br />

recession<br />

20 0 4<br />

20 06<br />

20 08<br />

2010<br />

Infrastucture<br />

investment<br />

surge spurs<br />

pickup<br />

2010<br />

2012<br />

2014<br />

2015<br />

Market<br />

wobbles and<br />

debt overhang<br />

cloud outlook<br />

2016<br />

Allianz • 51