New Scientist – June 10 2017

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

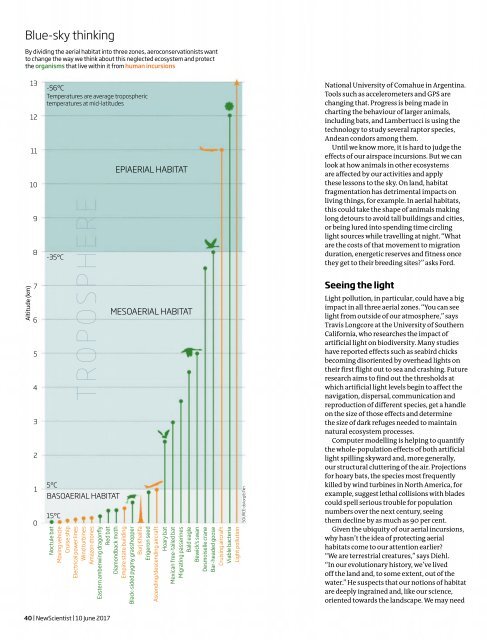

Blue-sky thinking<br />

By dividing the aerial habitat into three zones, aeroconservationists want<br />

to change the way we think about this neglected ecosystem and protect<br />

the organisms that live within it from human incursions<br />

Altitude (km)<br />

13<br />

12<br />

11<br />

<strong>10</strong><br />

9<br />

8<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

-56°C<br />

Temperatures are average tropospheric<br />

temperatures at mid-latitudes<br />

-35°C<br />

5°C<br />

BASOAERIAL HABITAT<br />

15°C<br />

TROPOSPH<br />

EPIAERIAL HABITAT<br />

MESOAERIAL HABITAT<br />

Noctule bat<br />

Moving vehicle<br />

Cruise ship<br />

Electrical power lines<br />

Wind turbines<br />

Amazon drones<br />

Eastern amberwing dragonly<br />

Red bat<br />

Diamondback moth<br />

Empire state building<br />

Black-sided pygmy grasshopper<br />

Burj Khalifa<br />

Erigeron seed<br />

Ascending/descending aircraft<br />

Hoary bat<br />

Mexican free-tailed bat<br />

Migrating passerines<br />

Bald eagle<br />

Bewick’s swan<br />

Desmoiselle crane<br />

Bar-headed goose<br />

Cruising aircraft<br />

Viable bacteria<br />

Light pollution<br />

SOURCE: doi.org/b7xn<br />

National University of Comahue in Argentina.<br />

Tools such as accelerometers and GPS are<br />

changing that. Progress is being made in<br />

charting the behaviour of larger animals,<br />

including bats, and Lambertucci is using the<br />

technology to study several raptor species,<br />

Andean condors among them.<br />

Until we know more, it is hard to judge the<br />

effects of our airspace incursions. But we can<br />

look at how animals in other ecosystems<br />

are affected by our activities and apply<br />

these lessons to the sky. On land, habitat<br />

fragmentation has detrimental impacts on<br />

living things, for example. In aerial habitats,<br />

this could take the shape of animals making<br />

long detours to avoid tall buildings and cities,<br />

or being lured into spending time circling<br />

light sources while travelling at night. “What<br />

are the costs of that movement to migration<br />

duration, energetic reserves and fitness once<br />

they get to their breeding sites?” asks Ford.<br />

Seeing the light<br />

Light pollution, in particular, could have a big<br />

impact in all three aerial zones. “You can see<br />

light from outside of our atmosphere,” says<br />

Travis Longcore at the University of Southern<br />

California, who researches the impact of<br />

artificial light on biodiversity. Many studies<br />

have reported effects such as seabird chicks<br />

becoming disoriented by overhead lights on<br />

their first flight out to sea and crashing. Future<br />

research aims to find out the thresholds at<br />

which artificial light levels begin to affect the<br />

navigation, dispersal, communication and<br />

reproduction of different species, get a handle<br />

on the size of those effects and determine<br />

the size of dark refuges needed to maintain<br />

natural ecosystem processes.<br />

Computer modelling is helping to quantify<br />

the whole-population effects of both artificial<br />

light spilling skyward and, more generally,<br />

our structural cluttering of the air. Projections<br />

for hoary bats, the species most frequently<br />

killed by wind turbines in North America, for<br />

example, suggest lethal collisions with blades<br />

could spell serious trouble for population<br />

numbers over the next century, seeing<br />

them decline by as much as 90 per cent.<br />

Given the ubiquity of our aerial incursions,<br />

why hasn’t the idea of protecting aerial<br />

habitats come to our attention earlier?<br />

“We are terrestrial creatures,” says Diehl.<br />

“In our evolutionary history, we’ve lived<br />

off the land and, to some extent, out of the<br />

water.” He suspects that our notions of habitat<br />

are deeply ingrained and, like our science,<br />

oriented towards the landscape. We may need<br />

40 | <strong>New</strong><strong>Scientist</strong> | <strong>10</strong> <strong>June</strong> <strong>2017</strong>