CONTENTS DIARY OF EVENTS - The Urban Design Group

CONTENTS DIARY OF EVENTS - The Urban Design Group

CONTENTS DIARY OF EVENTS - The Urban Design Group

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

VIEWPOINTS<br />

Reinventing Road Hierarchy<br />

Stephen Marshall suggests the possibility of reinventing ‘road hierarchy’ as<br />

part of a street-based urban code<br />

<strong>The</strong> historical transformation from traditional street-grids to the<br />

Modernist system of open plan, hierarchical road layouts and back<br />

to street-grids again must be one of the most significant reversals in<br />

urban design history. As part of the urban counter-revolution, mixeduse<br />

streets are now back in vogue, while old style roads-dominated<br />

approaches to urban layout are on the back foot. Yet, while a variety of<br />

professions and design guidance documents may now be sympathetic<br />

to the street-oriented urban design agenda, many of the principles<br />

which underpin urban layout are still to a significant extent based on<br />

Modernist ideas of road hierarchies and separate land use zones.<br />

<strong>The</strong>refore, although it is possible to design neat urbanistic enclaves<br />

such as Poundbury with official approval – as illustrated in the UK<br />

design guide Places, Streets and Movement – it is not so clear what<br />

happens when we come up against the main network of ‘distributor’<br />

roads. In other words, while neo-traditional style developments such<br />

as Poundbury may internally have an urbanistic ‘hierarchy’ of streets,<br />

squares and mews, this hierarchy effectively goes no further than the<br />

nearest distributor road, where it comes up against the constraints of<br />

conventional road hierarchy.<br />

‘GOOD’ AND ‘BAD’ HIERARCHY<br />

Although modern roads layouts are sometimes criticised for being<br />

hierarchical, urban designers and planners do sometimes appreciate<br />

some kind of hierarchy, whether as part of traditional unplanned or<br />

planned settlements. <strong>Design</strong> guides sometimes call for a recognisable<br />

hierarchy of streets and spaces; this may promote diversity of street<br />

type and legibility of the layout as a whole.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Craig Plan for Edinburgh’s Georgian New Town, despite being<br />

an ‘urbanistic grid’, employs a hierarchical structure similar to modern<br />

road layouts. <strong>The</strong> difference is that in the case of the Craig Plan, all the<br />

types are streets of one sort or another (streets, lanes, mews), and they<br />

connect ‘upwards’ to the main streets – that is, to focal ‘people places’,<br />

that form the main backbone or armature of urban structure.<br />

In contrast, in modern road layouts, streets only feature at the<br />

subordinate level of the access road. <strong>The</strong>re is no strategic focus for these<br />

14 | <strong>Urban</strong> <strong>Design</strong> | Spring 2005 | Issue 94<br />

streets; they often lead or connect ‘upwards’ only to the non-place<br />

disurban realm of the distributor road. In effect, the structural logic of<br />

conventional road hierarchy leads to a discontinuous scatter of street<br />

enclaves forming oases of urbanity in a desert of distributor roads.<br />

So the problem with modern urban layouts is not that they are<br />

hierarchical as such; but that they may use the ‘wrong’ combination of<br />

hierarchical elements for today’s taste – ‘wrong’, that is, for promoting<br />

mixed-use, walkable (and bus-catchable) urban neighbourhoods, rather<br />

than mono-use, car-oriented suburbs.<br />

Accordingly, to achieve more urbanistic layouts does not necessarily<br />

mean abandoning road hierarchy, but could mean reinventing it as a<br />

component of a wider urban code.<br />

HIERARCHY AS CODE<br />

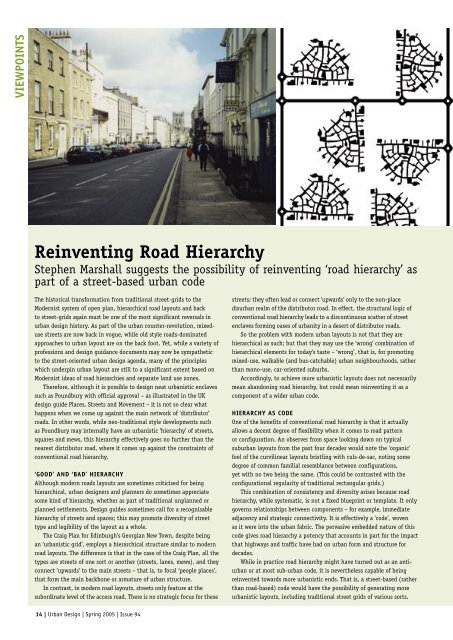

One of the benefits of conventional road hierarchy is that it actually<br />

allows a decent degree of flexibility when it comes to road pattern<br />

or configuration. An observer from space looking down on typical<br />

suburban layouts from the past four decades would note the ‘organic’<br />

feel of the curvilinear layouts bristling with culs-de-sac, noting some<br />

degree of common familial resemblance between configurations,<br />

yet with no two being the same. (This could be contrasted with the<br />

configurational regularity of traditional rectangular grids.)<br />

This combination of consistency and diversity arises because road<br />

hierarchy, while systematic, is not a fixed blueprint or template. It only<br />

governs relationships between components – for example, immediate<br />

adjacency and strategic connectivity. It is effectively a ‘code’, woven<br />

as it were into the urban fabric. <strong>The</strong> pervasive embedded nature of this<br />

code gives road hierarchy a potency that accounts in part for the impact<br />

that highways and traffic have had on urban form and structure for<br />

decades.<br />

While in practice road hierarchy might have turned out as an antiurban<br />

or at most sub-urban code, it is nevertheless capable of being<br />

reinvented towards more urbanistic ends. That is, a street-based (rather<br />

than road-based) code would have the possibility of generating more<br />

urbanistic layouts, including traditional street grids of various sorts.