You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Mike is not the kind of guy I expected to meet<br />

at a heli ski operation. But then again, none<br />

of this is what I expected. When I was given<br />

the chance to go on a Heli Safari with Last Frontier<br />

Heli, located up in the far reaches of Northern<br />

BC, Canada, I had figured it would be the classic<br />

Canadian heli/lodge experience, the experience<br />

the Canadian reputation is built on. But from the<br />

moment I arrived in Stewart – the first stop on our<br />

Safari – I had to rethink all of it.<br />

Stewart is a town built to support a mining industry<br />

that no longer exists. Situated at the end of the<br />

Portland Canal, Stewart sits about a half-mile<br />

from the border. A clear-cut through the forest<br />

separates it from neighbouring Hyder, Alaska,<br />

population 87.<br />

<strong>The</strong> wheels of industry turned here for almost 100<br />

years. <strong>The</strong>re was a time when the town swelled to<br />

many tens of thousands and business was good,<br />

a time when men from all over Canada flocked<br />

to work the silver mines, drink whisky and make<br />

more of themselves. But the landscape was harsh<br />

and unyielding. Giant glacial plateaus plunged<br />

into icy ocean fjords. Avalanches engulfed teams<br />

of men working the valleys below. Man, they must<br />

have tried. <strong>The</strong>y carved tunnels through rock, they<br />

shored up massive slipping hillsides, they cut trails<br />

through deep pine and hemlock forests, and they<br />

laid tracks along the shorefront to set up a goods<br />

line down south. But this was rough country,<br />

nobody got rich, and when the mines closed<br />

down and moved to more profitable locations the<br />

workers left with them.<br />

Today the town is all but dead. But the spirit of<br />

frontier life remains in the buildings that continue<br />

to line Main Street. Some are artfully restored in<br />

Pastel timber, like the Ripley Creek Inn and the<br />

Bitter Creek Café, with their cosy kitsch interiors<br />

and bric-a-brac from the silver rush, others less so.<br />

Down the road an original ‘57 Chevrolet Bel Air in<br />

jet blue sits in an old warehouse. It looks like it’s<br />

been driven once and then just left to sit.<br />

But where most would see only history, two<br />

salty old Swiss skiers and an Englishman saw<br />

something else. Like the miners of the early 20 th<br />

century, George Rossett, Franz Fux and Mike<br />

Watling saw opportunity where others saw nothing<br />

but wilderness. For the miners it was the rich silver<br />

veins in the upper Salmon River Basin, for Rossett,<br />

Fux and Watling, it was the 9,500km 2 of available<br />

tenure, packed with expansive glaciers, steep fallline<br />

forests and epically skiable peaks, making it<br />

the biggest single heli ski operation on Earth. In<br />

the middle of this skiing Nirvana, Last Frontier<br />

Heli was born.<br />

My arrival coincided with an Arctic outflow<br />

causing sub-arctic temperatures starting at minus<br />

25 degrees. Tundra-like conditions made the first<br />

two days unbearable. It was cold, it was dry, and it<br />

was hard. But then it snowed. After being sucked<br />

into the slipstream of the outflow, this low pressure<br />

dropped 50cms of the driest snow imaginable<br />

in a single night, lighter than Utah, lighter than<br />

Hokkaido, lighter than anything. I’ve never seen<br />

anything like it. I figured being a heli operation<br />

we couldn’t fly during a storm system, and that we<br />

would have to wait for the next blue bird to go up,<br />

but that very next morning we were out there in the<br />

field. What we saw was a landscape transformed;<br />

from an empty frostbitten Yukon to a deep winter<br />

wilderness. Pow.<br />

We couldn’t believe it. None of us, not even<br />

Watling himself had ever skied snow like that.<br />

It was all there in front of you, but there just<br />

wasn’t any resistance, there was no feedback, you<br />

couldn’t feel a single flake. It was so deep and yet<br />

so fast that even making simple turns through it<br />

was strange; less like skiing and more like moving<br />

through a medium, like being a ghost.<br />

“Having good tree line skiing is so important for<br />

a heli operation,” said Watling as we waited to<br />

drop the next run, “Otherwise you just don’t get<br />

to ski days like this.” I wasn’t at all accustomed<br />

to flying around in a helicopter in the middle of a<br />

42<br />

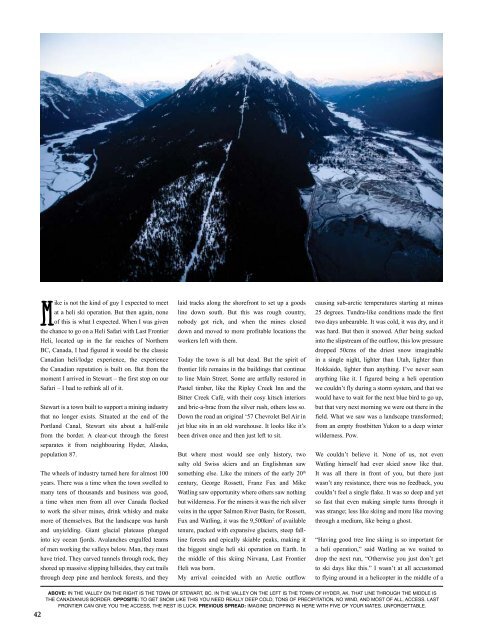

ABOVE: IN THE VALLEY ON THE RIGHT IS THE TOWN OF STEWART, BC. IN THE VALLEY ON THE LEFT IS THE TOWN OF HYDER, AK. THAT LINE THROUGH THE MIDDLE IS<br />

THE CANADIAN/US BORDER. OPPOSITE: TO GET SNOW LIKE THIS YOU NEED REALLY DEEP COLD, TONS OF PRECIPITATION, NO WIND, AND MOST OF ALL, ACCESS. LAST<br />

FRONTIER CAN GIVE YOU THE ACCESS, THE REST IS LUCK. PREVIOUS SPREAD: IMAGINE DROPPING IN HERE WITH FIVE OF YOUR MATES. UNFORGETTABLE.