Adventure Magazine

Issue #236 Xmas 2022

Issue #236

Xmas 2022

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

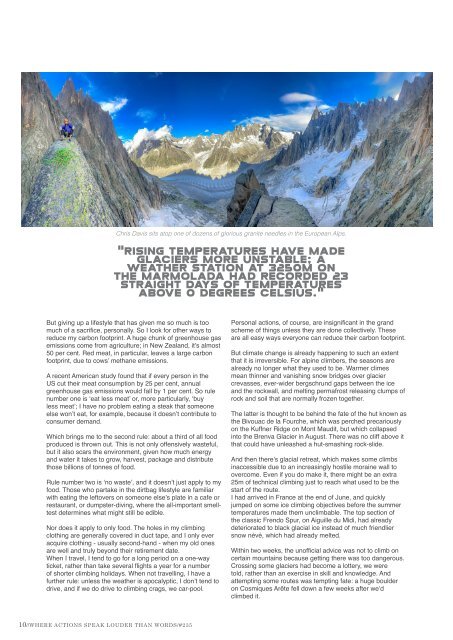

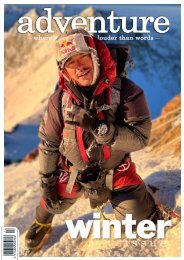

Chris Davis sits atop one of dozens of glorious granite needles in the European Alps.<br />

"rising temperatures have made<br />

glaciers more unstable; a<br />

weather station at 3250m on<br />

the Marmolada had recorded 23<br />

straight days of temperatures<br />

above 0 degrees Celsius."<br />

But giving up a lifestyle that has given me so much is too<br />

much of a sacrifice, personally. So I look for other ways to<br />

reduce my carbon footprint. A huge chunk of greenhouse gas<br />

emissions come from agriculture; in New Zealand, it’s almost<br />

50 per cent. Red meat, in particular, leaves a large carbon<br />

footprint, due to cows’ methane emissions.<br />

A recent American study found that if every person in the<br />

US cut their meat consumption by 25 per cent, annual<br />

greenhouse gas emissions would fall by 1 per cent. So rule<br />

number one is ‘eat less meat’ or, more particularly, ‘buy<br />

less meat’; I have no problem eating a steak that someone<br />

else won’t eat, for example, because it doesn’t contribute to<br />

consumer demand.<br />

Which brings me to the second rule: about a third of all food<br />

produced is thrown out. This is not only offensively wasteful,<br />

but it also scars the environment, given how much energy<br />

and water it takes to grow, harvest, package and distribute<br />

those billions of tonnes of food.<br />

Rule number two is ‘no waste’, and it doesn’t just apply to my<br />

food. Those who partake in the dirtbag lifestyle are familiar<br />

with eating the leftovers on someone else’s plate in a cafe or<br />

restaurant, or dumpster-diving, where the all-important smelltest<br />

determines what might still be edible.<br />

Nor does it apply to only food. The holes in my climbing<br />

clothing are generally covered in duct tape, and I only ever<br />

acquire clothing - usually second-hand - when my old ones<br />

are well and truly beyond their retirement date.<br />

When I travel, I tend to go for a long period on a one-way<br />

ticket, rather than take several flights a year for a number<br />

of shorter climbing holidays. When not travelling, I have a<br />

further rule: unless the weather is apocalyptic, I don’t tend to<br />

drive, and if we do drive to climbing crags, we car-pool.<br />

Personal actions, of course, are insignificant in the grand<br />

scheme of things unless they are done collectively. These<br />

are all easy ways everyone can reduce their carbon footprint.<br />

But climate change is already happening to such an extent<br />

that it is irreversible. For alpine climbers, the seasons are<br />

already no longer what they used to be. Warmer climes<br />

mean thinner and vanishing snow bridges over glacier<br />

crevasses, ever-wider bergschrund gaps between the ice<br />

and the rockwall, and melting permafrost releasing clumps of<br />

rock and soil that are normally frozen together.<br />

The latter is thought to be behind the fate of the hut known as<br />

the Bivouac de la Fourche, which was perched precariously<br />

on the Kuffner Ridge on Mont Maudit, but which collapsed<br />

into the Brenva Glacier in August. There was no cliff above it<br />

that could have unleashed a hut-smashing rock-slide.<br />

And then there’s glacial retreat, which makes some climbs<br />

inaccessible due to an increasingly hostile moraine wall to<br />

overcome. Even if you do make it, there might be an extra<br />

25m of technical climbing just to reach what used to be the<br />

start of the route.<br />

I had arrived in France at the end of June, and quickly<br />

jumped on some ice climbing objectives before the summer<br />

temperatures made them unclimbable. The top section of<br />

the classic Frendo Spur, on Aiguille du Midi, had already<br />

deteriorated to black glacial ice instead of much friendlier<br />

snow névé, which had already melted.<br />

Within two weeks, the unofficial advice was not to climb on<br />

certain mountains because getting there was too dangerous.<br />

Crossing some glaciers had become a lottery, we were<br />

told, rather than an exercise in skill and knowledge. And<br />

attempting some routes was tempting fate: a huge boulder<br />

on Cosmiques Arête fell down a few weeks after we’d<br />

climbed it.<br />

10//WHERE ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS/#235