Migrant Smuggling in Asia - United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

Migrant Smuggling in Asia - United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

Migrant Smuggling in Asia - United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

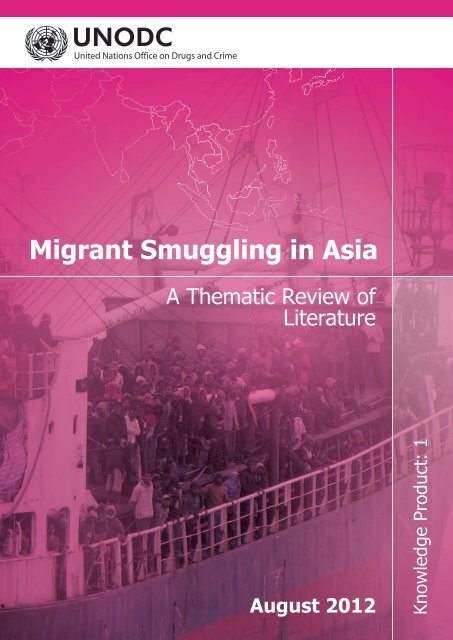

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

A Thematic Review of<br />

Literature<br />

August 2012<br />

Knowledge Product: 1

!"#$%&'()!*##+"&#("&(%)"%<br />

A �ematic Review of Literature

Pr<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ted: Bangkok, August 2012<br />

Authorship: <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> O�ce <strong>on</strong> <strong>Drugs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Crime</strong> (UNODC)<br />

Copyright © 2012, UNODC<br />

e-ISBN: 978-974-680-331-1<br />

�is publicati<strong>on</strong> may be reproduced <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> whole or <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> part <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> any form for educati<strong>on</strong>al or n<strong>on</strong>-pro�t<br />

purposes without special permissi<strong>on</strong> from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is<br />

made. UNODC would appreciate receiv<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g a copy of any publicati<strong>on</strong> that uses this publicati<strong>on</strong> as a source.<br />

No use of this publicati<strong>on</strong> may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior<br />

permissi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> writ<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g from the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> O�ce <strong>on</strong> <strong>Drugs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Crime</strong>. Applicati<strong>on</strong>s for such permissi<strong>on</strong>,<br />

with a statement of purpose <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>tent of the reproducti<strong>on</strong>, should be addressed to UNODC, Regi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Centre for East <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> the Paci�c.<br />

Cover photo: Courtesy of CBSA. �e photo shows a ship that was used <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> a migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g operati<strong>on</strong><br />

from <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> to North America.<br />

Product Feedback:<br />

Comments <strong>on</strong> the report are welcome <strong>and</strong> can be sent to:<br />

Coord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Analysis Unit (CAU)<br />

Regi<strong>on</strong>al Centre for East <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> the Paci�c<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> Build<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g, 3 rd Floor<br />

Rajdamnern Nok Avenue<br />

Bangkok 10200, �ail<strong>and</strong><br />

Fax: +66 2 281 2129<br />

E-mail: fo.thail<strong>and</strong>@unodc.org<br />

Website: www.unodc.org/eastasia<strong>and</strong>paci�c/<br />

UNODC gratefully acknowledges the �nancial c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong> of the Government of Australia that enabled the<br />

research for <strong>and</strong> the producti<strong>on</strong> of this publicati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Disclaimers:<br />

�is report has not been formally edited. �e c<strong>on</strong>tents of this publicati<strong>on</strong> do not necessarily re�ect the views<br />

or policies of UNODC <strong>and</strong> neither do they imply any endorsement. �e designati<strong>on</strong>s employed <strong>and</strong> the<br />

presentati<strong>on</strong> of material <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> this publicati<strong>on</strong> do not imply the expressi<strong>on</strong> of any op<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>i<strong>on</strong> whatsoever <strong>on</strong> the part<br />

of UNODC c<strong>on</strong>cern<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or c<strong>on</strong>cern<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the<br />

delimitati<strong>on</strong> of its fr<strong>on</strong>tiers or boundaries.

!,-./01()23--4,0-(,0(%5,/<br />

A �ematic Review of Literature<br />

A publicati<strong>on</strong> of the Coord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Analysis Unit<br />

of the Regi<strong>on</strong>al Centre for East <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> the Paci�c<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> O�ce <strong>on</strong> <strong>Drugs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Crime</strong>

'/647(89(:8017015(<br />

Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. 1<br />

Abbreviati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> acr<strong>on</strong>yms ................................................................................................................ 2<br />

List of diagrams <strong>and</strong> tables ................................................................................................................... 5<br />

Executive summary ............................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Policy recommendati<strong>on</strong>s for improv<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g evidence-based knowledge .................................................... 11<br />

Country situati<strong>on</strong> overview ................................................................................................................. 12<br />

Introduc<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the research methodology ............................................................................................... 24<br />

Chapter One: Cross-country �nd<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gs by thematic issues .................................................................... 31<br />

Introducti<strong>on</strong> .................................................................................................................................. 31<br />

How are migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> pers<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>ceptualized <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the literature? .............. 32<br />

What methodologies are be<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g used <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> research <strong>on</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> irregular migrati<strong>on</strong>? .. 34<br />

What <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> is available about stocks <strong>and</strong> �ows of irregular <strong>and</strong> smuggled migrants? .......... 37<br />

What are the major routes <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>volved <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g? ..................... 41<br />

What is known about the pro�les <strong>and</strong> motives of migrant smugglers? ........................................... 41<br />

What is known about the pro�le of irregular <strong>and</strong> smuggled migrants? .......................................... 44<br />

What is known about the nature or characteristics of relati<strong>on</strong>ships between migrant smugglers<br />

<strong>and</strong> smuggled migrants? ................................................................................................................. 45<br />

What is known about the organizati<strong>on</strong> of migrant smugglers? ...................................................... 48<br />

What is known about the modus oper<strong>and</strong>i of smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g? .............................................................. 50<br />

What is known about migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g fees <strong>and</strong> their mobilizati<strong>on</strong>? .......................................... 56<br />

What is known about the human <strong>and</strong> social costs of migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g? ...................................... 59<br />

Factors that fuel irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g ........................................................ 62<br />

C<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> .................................................................................................................................... 63<br />

Chapter Two: Afghanistan .................................................................................................................. 69<br />

Chapter �ree: Cambodia ................................................................................................................... 83<br />

Chapter Four: Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a ........................................................................................................................... 93<br />

Chapter Five: India ........................................................................................................................... 115<br />

Chapter Six: Ind<strong>on</strong>esia ...................................................................................................................... 131<br />

Chapter Seven: Lao People’s Democratic Republic ........................................................................... 143<br />

Chapter Eight: Malaysia ................................................................................................................... 153<br />

Chapter N<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>e: Maldives .................................................................................................................... 163<br />

Chapter Ten: Myanmar ..................................................................................................................... 167<br />

Chapter Eleven: Pakistan .................................................................................................................. 177<br />

Chapter Twelve: S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore ................................................................................................................ 191<br />

Chapter �irteen: Sri Lanka ............................................................................................................. 197<br />

Chapter Fourteen: �ail<strong>and</strong> .............................................................................................................. 203<br />

Chapter Fifteen: Viet Nam ................................................................................................................ 215<br />

Annexes ............................................................................................................................................. 223<br />

Annex A: Complete list of databases, catalogues <strong>and</strong> websites searched ....................................... 225<br />

Annex B: Table of criteria to use for <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>itial bibliographic searches ............................................... 228<br />

Annex C: Key words used <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the annotated bibliography ............................................................. 229

%;-727015<br />

!"#!""$%&%'(#)*+,*$-.&/01<br />

�is publicati<strong>on</strong> was produced by the Regi<strong>on</strong>al Centre for East <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> the Paci�c (RCEAP) of UNODC,<br />

under the supervisi<strong>on</strong> of Sebastian Baumeister, Coord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Analysis Unit (CAU, UNODC).<br />

Lead researcher:<br />

Fi<strong>on</strong>a David (c<strong>on</strong>sultant).<br />

Research c<strong>on</strong>ceptualizati<strong>on</strong>, coord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> report preparati<strong>on</strong>:<br />

Sebastian Baumeister <strong>and</strong> Fi<strong>on</strong>a David.<br />

Report written by:<br />

Introduc<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the research methodology: Fi<strong>on</strong>a David; Chapter One: Fi<strong>on</strong>a David; Chapter Two: Fi<strong>on</strong>a David,<br />

Kenneth Wright (c<strong>on</strong>sultant); Chapter �ree: Rebecca Powell (c<strong>on</strong>sultant); Chapter Four: Fi<strong>on</strong>a David, Kenneth<br />

Wright; Chapter Five: Rebecca Miller (c<strong>on</strong>sultant); Chapter Six: Kather<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>e Rogers (c<strong>on</strong>sultant); Chapter<br />

Seven: Rebecca Powell; Chapter Eight: Kather<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>e Rogers; Chapter N<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>e: Rebecca Miller; Chapter Ten: Kenneth<br />

Wright; Chapter Eleven: Rebecca Miller; Chapter Twelve: Kather<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>e Rogers; Chapter �irteen: Rebecca<br />

Miller; Chapter Fourteen: Rebecca Powell; Chapter Fifteen: Fi<strong>on</strong>a David, Chapter Fifteen: Fi<strong>on</strong>a David,<br />

Kenneth Wright; Executive summary <strong>and</strong> Country situati<strong>on</strong> overview: Sebastian Baumeister.<br />

Editorial <strong>and</strong> producti<strong>on</strong> team:<br />

Sebastian Baumeister, Julia Brown (UNODC <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>tern), Fi<strong>on</strong>a David, Karen Emm<strong>on</strong>s (c<strong>on</strong>tractor, edit<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g),<br />

Ajcharaporn Lorlamai (CAU, UNODC), Coll<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Piprell (c<strong>on</strong>tractor, edit<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g), Siraphob Ruedeeniyomvuth<br />

(c<strong>on</strong>tractor, design), <strong>and</strong> Sanya Umasa (CAU, UNODC).<br />

Particular appreciati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> gratitude for support <strong>and</strong> advice go to Julia Brown, Elzbieta Gozdziak, Shawn<br />

Kelly (UNODC), Janet Smith from the Australian Institute of Crim<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ology, Tun Nay Soe (UNODC), <strong>and</strong><br />

to the sta� from the Library at the Australian Nati<strong>on</strong>al University.<br />

�e publicati<strong>on</strong> also bene�ted from the work <strong>and</strong> expertise of UNODC sta� members around the world.<br />

1

2<br />

2*-.&"%#345--,*"-#*"#!6*&<br />

%66.7?,/1,805(/0>(%;.80@25<br />

ARCM <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g>n Research Center for Migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

ARTWAC Acti<strong>on</strong> Research <strong>on</strong> Tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Women <strong>and</strong> Children<br />

ASEAN Associati<strong>on</strong> of Southeast <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g>n <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

BBC British Broadcast<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g Corporati<strong>on</strong><br />

BEFARE Basic Educati<strong>on</strong> for Awareness Reforms <strong>and</strong> Empowerment<br />

BEOE Bureau of Emigrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Overseas Employment<br />

CASS Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese Academy of Social Sciences<br />

CAU Coord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Analysis Unit of RCEAP, UNODC<br />

CECC C<strong>on</strong>gressi<strong>on</strong>al-Executive Commissi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a<br />

CIA Central Intelligence Agency<br />

CIAO Columbia Internati<strong>on</strong>al A�airs Onl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>e<br />

CIS Comm<strong>on</strong>wealth of Independent States<br />

COMCAD Center <strong>on</strong> Migrati<strong>on</strong>, Citizenship <strong>and</strong> Development<br />

CNY Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese Renm<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>bi<br />

CRS C<strong>on</strong>gressi<strong>on</strong>al Research Service<br />

CTV Canadian Televisi<strong>on</strong> Network<br />

DGSN Directi<strong>on</strong> Générale de la Sûreté Nati<strong>on</strong>ale (the Moroccan nati<strong>on</strong>al security service)<br />

EBDM Enterprise for Bus<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ess & Development Management<br />

ERTV Ec<strong>on</strong>omic Rehabilitati<strong>on</strong> of Tra�cked Victims<br />

EU European Uni<strong>on</strong><br />

EUR Euro<br />

FATA Federally Adm<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>istered Tribal Areas<br />

FDI Foreign Direct Investment<br />

FIA Federal Investigati<strong>on</strong> Agency<br />

FSA Foreign Service Agreements<br />

GBP <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom Pound<br />

GDP Gross Domestic Product<br />

GMS Greater Mek<strong>on</strong>g Subregi<strong>on</strong><br />

HIV/AIDS Human Immunode�ciency Virus/Acquired Immunode�ciency Syndrome<br />

HRCP Human Rights Commissi<strong>on</strong> of Pakistan<br />

IBSS Internati<strong>on</strong>al Bibliography of the Social Sciences

IDPs Internally Displaced Pers<strong>on</strong>s<br />

IIED Internati<strong>on</strong>al Institute for Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <strong>and</strong> Development<br />

ILO Internati<strong>on</strong>al Labour Organizati<strong>on</strong><br />

IMISCOE Internati<strong>on</strong>al Migrati<strong>on</strong>, Integrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Social Cohesi<strong>on</strong><br />

INGO Internati<strong>on</strong>al N<strong>on</strong>governmental Organizati<strong>on</strong><br />

IOM Internati<strong>on</strong>al Organizati<strong>on</strong> for Migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

IPSR Institute for Populati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> Social Research<br />

ISS Institute of Social Sciences<br />

IVTS Informal Value Transfer Systems<br />

KWAT Kach<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Women’s Associati<strong>on</strong> �ail<strong>and</strong><br />

Lao PDR Lao People’s Democratic Republic<br />

LTTE Liberati<strong>on</strong> Tigers of Tamil Eelam<br />

MAIS Multicultural Aust. & Immigrati<strong>on</strong> Studies<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Protocol<br />

MMK Myanmar Kyat<br />

MNA M<strong>on</strong> News Agency<br />

MYR Malaysia R<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ggit<br />

!#70'4&%*8#9':*';#$

4<br />

2*-.&"%#345--,*"-#*"#!6*&<br />

SAARC South <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g>n Associati<strong>on</strong> for Regi<strong>on</strong>al Cooperati<strong>on</strong><br />

SEPOM Self-Empowerment Program for <str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g> Women<br />

SGD S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore Dollar<br />

SIEV Suspected Illegal Entry Vessel<br />

THB �ai Baht<br />

TiP Tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pers<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Pers<strong>on</strong>s Protocol<br />

UAE <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> Arab Emirates<br />

UK <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom<br />

UN <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Protocol to Prevent, Suppress <strong>and</strong> Punish Tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pers<strong>on</strong>s, especially Women<br />

<strong>and</strong> Children, supplement<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the UN C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> Aga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>st Transnati<strong>on</strong>al Organized<br />

<strong>Crime</strong><br />

UNAIDS <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> Programme <strong>on</strong> HIV/AIDS<br />

UNDP <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> Development Programme<br />

UNESCAP <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ec<strong>on</strong>omic <strong>and</strong> Social Commissi<strong>on</strong> for <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> the Paci�c<br />

UNFPA <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> Populati<strong>on</strong> Fund<br />

UN.GIFT <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> Global Initiative to Fight Human Tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

UNHCR <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> High Commissi<strong>on</strong>er for Refugees<br />

UNICEF <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> Children’s Fund<br />

UNIAP <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> Inter-Agency Project <strong>on</strong> Human Tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

UNIFEM <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> Development Fund for Women<br />

UNODC <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> O�ce <strong>on</strong> <strong>Drugs</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Crime</strong><br />

UNTOC <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> aga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>st Transnati<strong>on</strong>al Organized <strong>Crime</strong><br />

USD <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> States Dollar<br />

USSR Uni<strong>on</strong> of Soviet Socialist Republics<br />

WVFT World Visi<strong>on</strong> Foundati<strong>on</strong> of �ail<strong>and</strong><br />

YCOWA Yaung Chi Oo Workers’ Associati<strong>on</strong>

+,51(89(>,/-./25(/0>(1/6475(<br />

!#70'4&%*8#9':*';#$

6<br />

2*-.&"%#345--,*"-#*"#!6*&<br />

AB7;31,?7()322/.@<br />

Objective <strong>and</strong> methodology<br />

�e <str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g>: A �ematic Review of<br />

Literature <strong>and</strong> the accompany<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g annotated bibliography<br />

o�er a c<strong>on</strong>solidati<strong>on</strong> of �nd<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gs c<strong>on</strong>ta<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ed <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

research literature that analyses migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> either directly or <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>directly. �e review of<br />

the available body of empirical knowledge aimed<br />

to create an <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> base <strong>and</strong> identify the<br />

gaps <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> what is known about the smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g of migrants<br />

around <strong>and</strong> out of the regi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

By c<strong>on</strong>solidat<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> currently accessible<br />

<strong>on</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g, the �ematic Review of<br />

Literature looks to stimulate <strong>and</strong> guide further research<br />

that will c<strong>on</strong>tribute to <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>form<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g evidencebased<br />

policies to prevent <strong>and</strong> combat the smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

of migrants while uphold<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> protect<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the<br />

rights of those who are smuggled.<br />

�e <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> O�ce <strong>on</strong> <strong>Drugs</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>Crime</strong> (UNODC) c<strong>on</strong>ducted the research <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> support<br />

of the Bali Process, which is a regi<strong>on</strong>al, multilateral<br />

process to improve cooperati<strong>on</strong> aga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>st migrant<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g, tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> pers<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> related forms<br />

of transnati<strong>on</strong>al crime.<br />

�e systematic search for research literature <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

English, French <strong>and</strong> German covered an eight-year<br />

period (1 January 2004 to 31 March 2011) <strong>and</strong> 14<br />

countries (Afghanistan, Cambodia, Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a, India, Ind<strong>on</strong>esia,<br />

Lao PDR, Malaysia, Maldives, Myanmar, Pakistan,<br />

S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore, Sri Lanka, �ail<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Viet Nam).<br />

Primary research, such as the collecti<strong>on</strong> of statistics<br />

from nati<strong>on</strong>al authorities, was not part of the project.<br />

�e project began with a search of 44 databases, <strong>on</strong>e<br />

meta-library catalogue, three <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>stituti<strong>on</strong>-speci�c library<br />

catalogues <strong>and</strong> 39 websites of <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>stituti<strong>on</strong>s that<br />

work <strong>on</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g. �is resulted <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> 845 documents<br />

that were then closely reviewed aga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>st a set of<br />

further elaborated criteria. Ultimately, 154 documents<br />

were critically reviewed <strong>and</strong> formed the basis of this<br />

report. Abstracts of those documents are provided <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g>: An Annotated Bibliography.<br />

�e systematic search also <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>cluded literature regard<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> human tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g �ows<br />

not <strong>on</strong>ly because migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g takes place<br />

with<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> but to learn more about<br />

the relati<strong>on</strong>ship between migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g, irregular<br />

migrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> human tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g.<br />

A highly fragmented <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> base: Knowledge<br />

gaps prevail<br />

Of the 154 documents reviewed, 75 of them provided<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> about migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g, 117<br />

provided <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> about irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

66 provided <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> about human tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g.<br />

Keep<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>d that some countries with<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the<br />

research scope are major sources of migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> irregular migrati<strong>on</strong>, these �gures illustrate<br />

that migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g has not attracted a critical<br />

amount of attenti<strong>on</strong> with<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the research community.<br />

Accurate data <strong>on</strong> the extent of migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

either rarely exists or could not be accessed by researchers.<br />

�e reviewed literature re�ects the paucity<br />

of <strong>and</strong>/or shortcom<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gs <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> o�cial quantitative<br />

data <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> many countries <strong>and</strong> the di�culties <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> access<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

data that would allow a better grasp of both the<br />

extent of irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> to what extent irregular<br />

migrati<strong>on</strong> is facilitated by migrant smugglers.<br />

�e available research literature <strong>on</strong> irregular migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

c<strong>on</strong>tributes <strong>on</strong>ly <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> a limited way to <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>creas<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

the underst<strong>and</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g of migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

due to a lack of clarity with the term<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ology. Comm<strong>on</strong><br />

is the use of terms that are not further de�ned,<br />

such as “illegal migrant”, “broker”, “agent” <strong>and</strong> “recruiter”.<br />

�is ambiguity signi�cantly has limited the<br />

capacity of the literature <strong>on</strong> irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> to<br />

clarify to what extent migrant smugglers facilitate<br />

irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> how.<br />

�e available research <strong>on</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>on</strong>ly<br />

focuses <strong>on</strong> a few types of �ows or <strong>on</strong> a few thematic<br />

issues. �ere is some dedicated research <strong>on</strong> migrant<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g from Afghanistan <strong>and</strong> Pakistan (ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ly<br />

to Europe <strong>and</strong> speci�cally the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom), <strong>on</strong><br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g from India (to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom), <strong>on</strong><br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g from Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> States <strong>and</strong>, to

a lesser extent, to Europe; <strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong> the organizati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

forms of smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g. Yet amaz<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gly, there is very limited<br />

research <strong>on</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g: from Sri Lanka;<br />

to the Maldives; to S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore; to <strong>and</strong> through Ind<strong>on</strong>esia<br />

<strong>and</strong> Malaysia; from Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a to dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong>s other<br />

than the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> States <strong>and</strong> European countries; from<br />

Viet Nam to countries other than the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom;<br />

<strong>and</strong> <strong>on</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g with<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Greater<br />

Mek<strong>on</strong>g Subregi<strong>on</strong>. �ere is very limited research <strong>on</strong><br />

thematic aspects, such as to what extent does migrant<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g fuel human tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> irregular migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

or who are the migrant smugglers. Most of<br />

the thematic research questi<strong>on</strong>s that guided this literature<br />

review could <strong>on</strong>ly be answered partially or an<br />

answer was based up<strong>on</strong> a th<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> body of <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

�e good news: High-quality research <strong>on</strong> migrant<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g is feasible<br />

A number of research studies signi�cantly c<strong>on</strong>tribute<br />

to <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>creas<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the knowledge about migrant<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g. �ose studies used qualitative research<br />

methods, such as semi-structured <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>terviews, observati<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tent analysis of documents. Other<br />

research drew <strong>on</strong> quantitative data that was already<br />

available or was generated for the purpose of the<br />

research, such as through household surveys (structured<br />

questi<strong>on</strong>naires). �e research drew up<strong>on</strong> a variety<br />

of sources: smuggled migrants, migrant smugglers<br />

or experts were <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>terviewed; regularizati<strong>on</strong> statistics,<br />

deportati<strong>on</strong> statistics or statistics such as the number<br />

of facilitated illegal entries were analysed; data from<br />

crim<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>al justice proceed<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gs, such as �les from <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>vestigati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong> prosecuti<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>ta<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g><str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>terrogati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

<strong>and</strong>/or teleph<strong>on</strong>e <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>tercepti<strong>on</strong>s, were exam<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ed.<br />

F<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>d<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gs by country<br />

Aga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>st this backdrop of an uneven, sketchy <strong>and</strong><br />

limited <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> base, the follow<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g part summarizes<br />

the ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> �nd<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gs about migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

with regard to the 14 reviewed countries:<br />

South-West <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Afghanistan<br />

Irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> of Afghan citizens is largely organized<br />

by Pakistani <strong>and</strong> Afghan smugglers, while<br />

the actual smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g services are carried out by citi-<br />

!#70'4&%*8#9':*';#$

8<br />

2*-.&"%#345--,*"-#*"#!6*&<br />

half of the 2000s, migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g fees for a direct<br />

�ight to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom were between USD<br />

13,000 <strong>and</strong> USD 14,000. More recent research <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>dicates<br />

fees of between USD 18,000 <strong>and</strong> USD 26,000<br />

for <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>direct �ights to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> States via Bangkok.<br />

West <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

India<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g> smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g from the states of Tamil Nadu <strong>and</strong><br />

Punjab is extensive. It has also spread <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>to the neighbour<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

states of Haryana, Himachal Pradesh <strong>and</strong><br />

Jammu <strong>and</strong> Kashmir. From the southern state of Tamil<br />

Nadu, irregular migrants leave ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ly for the Middle<br />

East <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong>, to a lesser extent (around 25 per<br />

cent), to Europe. More than an estimated 20,000 migrants<br />

irregularly leave Punjab each year. Almost half<br />

of the annual departures of Punjab migrants allegedly<br />

head to Europe, <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> particular the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom.<br />

�is re�ects that irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> largely mirrors<br />

patterns of regular migrati<strong>on</strong> �ows. Other dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong><br />

countries <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>clude Australia, Canada, Japan, Malaysia,<br />

Republic of Korea, S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore, South Africa, �ail<strong>and</strong>,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> Arab Emirates <strong>and</strong> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> States. Smugglers<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Tamil Nadu <strong>and</strong> Punjab often operate under<br />

the guise of travel or recruitment agencies. Indian<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g networks are highly professi<strong>on</strong>al <strong>and</strong> realize<br />

substantial pro�ts. �ey organize complex travel<br />

through various countries, obta<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> high-quality fraudulent<br />

documents, <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>clud<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g genu<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>e documents obta<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ed<br />

<strong>on</strong> fraudulent grounds, <strong>and</strong> o�er m<strong>on</strong>ey-back<br />

guarantees. Often legally resid<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> transit countries,<br />

Indian smugglers ensure the overall coord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong> of the<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g process <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> cooperati<strong>on</strong> with n<strong>on</strong>-Indians<br />

who facilitate the actual smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g work <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the transit<br />

countries. Reported fees range from USD 1,700 for<br />

dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Middle East to USD 13,000 for<br />

Europe <strong>and</strong> even higher for North America.<br />

Maldives <strong>and</strong> Sri Lanka<br />

Empirically based research <strong>on</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

regard<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the Maldives <strong>and</strong> Sri Lanka is completely<br />

lack<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g. Accord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g to <strong>on</strong>e source, there are some<br />

30,000 irregular migrants <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Maldives (an estimated<br />

37.5 percent of all work<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g migrants); another<br />

source reported that an estimated half of the<br />

35,000 Bangladeshis who entered the Maldives did<br />

so without authorizati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g>s from Sri Lanka resort to various, often<br />

complex <strong>and</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g routes to their dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong>s. Tam-<br />

ils, for example, are smuggled via India to countries<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Europe. In additi<strong>on</strong> to Greece, France, Italy <strong>and</strong><br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom, Canada is a comm<strong>on</strong> dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Only media sources provide <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> about<br />

migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g via boat to Australia <strong>and</strong> Canada.<br />

Some media reports claimed that migrant smugglers<br />

charged up to USD 5,000 for a journey to Europe,<br />

Australia or Canada. Other media reports claimed<br />

that Sri Lankans had paid as much as USD 50,000<br />

per pers<strong>on</strong> to be smuggled by boat to Canada.<br />

South-East <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Ind<strong>on</strong>esia <strong>and</strong> Malaysia<br />

Irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> from Ind<strong>on</strong>esia mirrors regular<br />

migrati<strong>on</strong> patterns, with Malaysia as the primary<br />

country of dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong>. Malaysia is also a country of<br />

dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong> for irregular migrants from other countries,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> particular Philipp<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>es. Research from 2009<br />

<strong>and</strong> 2010 <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>cludes estimates of irregular migrants <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Malaysia at between 600,000 to 1.9 milli<strong>on</strong>. Most<br />

of the irregular migrants are from Ind<strong>on</strong>esia <strong>and</strong><br />

Philipp<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>es, but they also come from Bangladesh,<br />

Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Nepal <strong>and</strong> �ail<strong>and</strong>.<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are predom<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>antly smuggled by l<strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> sea <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>to Malaysia. Between Ind<strong>on</strong>esia <strong>and</strong> Malaysia,<br />

there is a great deal of overlap between regular<br />

<strong>and</strong> irregular labour migrati<strong>on</strong>, migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> human tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g. �e volume of Ind<strong>on</strong>esian<br />

victims of human tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g found <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Malaysia illustrates<br />

that irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> irregular overstay<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

leave migrants vulnerable to exploitati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

human tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g. Even though the use of regular<br />

labour migrati<strong>on</strong> channels does not protect aga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>st<br />

abuse, exploitati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> human tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g, the reviewed<br />

literature underscores that up<strong>on</strong> arrival, irregular<br />

migrants are more vulnerable to tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

than regular migrants. Regard<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g irregular migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

from Ind<strong>on</strong>esia to Malaysia, the geographic proximity,<br />

porous borders <strong>and</strong> well-established migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

�ows are factors <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> its popularity; it is driven by<br />

shortcom<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gs <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the regular labour migrati<strong>on</strong> system<br />

<strong>and</strong> is largely facilitated by migrant smugglers.<br />

Avoid<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the relatively high costs associated with<br />

regular labour migrati<strong>on</strong> is po<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ted out as a major<br />

reas<strong>on</strong> for migrants to choose irregular channels.<br />

Ind<strong>on</strong>esia <strong>and</strong> Malaysia are also transit countries for<br />

smuggled migrants from the Middle East, South-<br />

West <strong>and</strong> West <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> want<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g to reach Australia by<br />

sea. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g>s us<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g this route claim to seek asylum

or are refugees; <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>security <strong>and</strong> better ec<strong>on</strong>omic prospects<br />

are major driv<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g factors. Other motivat<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

factors <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>clude family reuni�cati<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> the lengthy<br />

wait for resettlement of refugees. Us<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g Ind<strong>on</strong>esia as<br />

the po<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>t of embarkati<strong>on</strong>, some transit migrants enter<br />

directly by air. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are also smuggled <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>to<br />

Ind<strong>on</strong>esia from Malaysia by l<strong>and</strong>, sea <strong>and</strong> air — if<br />

direct entry <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>to Ind<strong>on</strong>esia is not an opti<strong>on</strong>. Corrupti<strong>on</strong><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> both Ind<strong>on</strong>esia <strong>and</strong> Malaysia is frequently<br />

cited as an important means to facilitate transit<br />

�ows. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g</str<strong>on</strong>g> fees vary <strong>and</strong> reach up to USD<br />

20,000. Fully pre-arranged smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g services from<br />

the Middle East <strong>and</strong> West or South <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g> through Ind<strong>on</strong>esia<br />

to Australia are less expensive than the sum<br />

of services paid for piece by piece.<br />

S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore<br />

Irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> to S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore is estimated to be<br />

not signi�cant <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> numbers. �is is due to its geographic<br />

positi<strong>on</strong> <strong>and</strong> to the enforcement of strict<br />

migrati<strong>on</strong> policies that were put <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> place before<br />

migrati<strong>on</strong> to S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore evolved. Research from the<br />

mid-2000s expla<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore was used as a<br />

transit po<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>t for migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g from Afghanistan,<br />

the Middle East <strong>and</strong> North Africa to Australia.<br />

Little <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> is provided about migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

from Malaysia to S<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gapore other than Bangladeshi,<br />

Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese, Myanmar <strong>and</strong> Nepalese nati<strong>on</strong>als are<br />

smuggled by boat.<br />

Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar <strong>and</strong> �ail<strong>and</strong><br />

�ail<strong>and</strong> is the major dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong> for irregular migrants<br />

from Cambodia, Lao PDR <strong>and</strong>, most heavily,<br />

Myanmar. Various estimates over the past decade<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>dicate a steady <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>crease of irregular migrants <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>to<br />

�ail<strong>and</strong>. Accord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g to more recent estimates, some<br />

2 milli<strong>on</strong> irregular Myanmar migrants (<strong>and</strong> around<br />

140,000 Myanmar refugees) are <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> �ail<strong>and</strong>. Poverty,<br />

the lack of ga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ful employment <strong>and</strong> the prospects<br />

of higher earn<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gs to support families back<br />

home are signi�cantly motivat<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the decisi<strong>on</strong> to<br />

irregularly migrate. Well-established social networks<br />

that facilitate the process <strong>and</strong> stories of others’ successful<br />

migrati<strong>on</strong> experiences are additi<strong>on</strong>al factors<br />

that encourage irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> from Cambodia,<br />

Lao PDR <strong>and</strong> Myanmar. Myanmar migrati<strong>on</strong> is<br />

also partially motivated by political factors <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>security.<br />

Borders <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Greater Mek<strong>on</strong>g Subregi<strong>on</strong><br />

can be crossed with ease. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g>s irregularly pass<br />

through o�cial checkpo<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ts <strong>and</strong> unauthorized border<br />

cross<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gs with or without assistance. �e use of<br />

!#70'4&%*8#9':*';#$

10<br />

2*-.&"%#345--,*"-#*"#!6*&<br />

irregular migrants were found <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the Republic of Korea.<br />

Typically, smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g routes transit Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a <strong>and</strong>/or<br />

Russia <strong>and</strong> Eastern Europe before reach<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g Central<br />

<strong>and</strong> Western Europe. Vietnamese smugglers rarely<br />

outsource smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g services to n<strong>on</strong>-Vietnamese<br />

smugglers, although the research <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>dicates that they<br />

cooperate with n<strong>on</strong>-Vietnamese smugglers, such as<br />

Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese <strong>and</strong> Czech nati<strong>on</strong>als, <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g of<br />

Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese citizens. More recent irregular migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

from Viet Nam to Europe orig<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ated <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> North Viet<br />

Nam, <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> particular <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the prov<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ces of Hai Ph<strong>on</strong>g<br />

<strong>and</strong> its neighbour Quang N<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>h. Some Vietnamese<br />

irregular migrants go to Canada or the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom<br />

to work <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> illegal cannabis cultivati<strong>on</strong> operati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

run by Vietnamese networks. However, the research<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom underscores that the<br />

smugglers did not engage <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the illegal cannabis cultivati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Smugglers o�er end-to-end services from<br />

Viet Nam to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom <strong>and</strong> frequently<br />

resort to fraudulent documents, <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>clud<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g look-alike<br />

documents. Genu<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>e documents are reportedly sold<br />

by Vietnamese migrants who have returned. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

fees to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom range from USD<br />

19,700 to USD 24,600.<br />

East <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a<br />

Irregular Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese migrants orig<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ate predom<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>antly<br />

from the southern prov<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ces of Fujian <strong>and</strong> Zhejiang,<br />

which have a history of outmigrati<strong>on</strong>. �e<br />

north-eastern prov<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ces of Lia<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g, Jil<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>and</strong> Heil<strong>on</strong>gjiang,<br />

however, have emerged more recently as<br />

send<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g regi<strong>on</strong>s also. Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese irregular migrants are<br />

ma<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ly driven by ec<strong>on</strong>omic ambiti<strong>on</strong>s but <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> comb<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong><br />

with other factors; networks, a history of<br />

migrati<strong>on</strong>, know<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g somebody who migrated <strong>and</strong><br />

the successful role models of returned migrants also<br />

motivate the decisi<strong>on</strong> to migrate. Diaspora communities<br />

functi<strong>on</strong> as a pull factor. Dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong>s of irregular<br />

Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese migrants are neighbour<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> Western<br />

countries: H<strong>on</strong>g K<strong>on</strong>g (Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a), Japan, Lao PDR,<br />

Myanmar, Republic of Korea, Taiwan Prov<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ce of<br />

Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a <strong>and</strong> Viet Nam; European countries, with the<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom as the top dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong>; Canada <strong>and</strong><br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> States; <strong>and</strong> Australia <strong>and</strong> New Zeal<strong>and</strong>.<br />

Central <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g>n <strong>and</strong> Eastern European countries serve<br />

as transit countries to Europe. Central America,<br />

Mexico <strong>and</strong> Canada are also transit countries for<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g routes <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> States. �ere are<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly a few estimates regard<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the numbers of Chi-<br />

nese irregular migrants: 250,000 irregular Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese<br />

migrants <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Moscow <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the mid-1990s, 72,000 <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the Republic of Korea <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> 2002; 30,000–40,000 entered<br />

the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> States annually from 2000 to 2005.<br />

Even though some of the researchers acknowledged<br />

the possibility of bias through the methodology<br />

chosen, the research <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>dicates that <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> general smugglers<br />

do not engage <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> crim<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>al activities other than<br />

migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g. Research carried out <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Italy,<br />

the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> K<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gdom found no<br />

evidence of Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese smugglers engaged <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> human<br />

tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g, for <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>stance. N<strong>on</strong>etheless, the research<br />

stresses that factors l<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ked to irregular migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

(fear<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g deportati<strong>on</strong>, not able to report to the police<br />

when becom<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g a victim of crime), debts <strong>and</strong> the<br />

excessive work<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g hours c<strong>on</strong>siderably raise the vulnerability<br />

of Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese migrants to abuse, harsh <strong>and</strong><br />

precarious liv<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> work<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, exploitati<strong>on</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> human tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g.<br />

Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese irregular migrants pay the highest smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

fees <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> comparis<strong>on</strong> with other populati<strong>on</strong>s of irregular<br />

migrants. Recent �gures range from USD 18,500<br />

to USD 31,300 for European dest<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> from<br />

USD 60,000 to USD 70,000 for an arranged marriage<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>to the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g> States. �e less a potential<br />

migrant is pers<strong>on</strong>ally c<strong>on</strong>nected to a smuggler, the<br />

higher the fee. Mutual trust is paramount. Both migrants<br />

<strong>and</strong> smugglers screen each other; smugglers<br />

want to determ<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>e if the possible migrants can pay,<br />

while migrants want to ensure that the smugglers will<br />

deliver the agreed service. Guaranteed schemes, such<br />

as <strong>on</strong>ly pay<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g for successfully completed smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

operati<strong>on</strong>s, are ways to attract migrants <strong>and</strong> build<br />

a good reputati<strong>on</strong>. �e smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g of Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese citizens<br />

is coord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ated by a cha<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> of Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese smugglers<br />

based <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>a <strong>and</strong> transit countries <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> which they<br />

legally reside. Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese smugglers might outsource<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g services to other n<strong>on</strong>-Ch<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ese groups <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

transit countries. Together, they form a small, �exible<br />

network that changes accord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g to bus<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ess opportunities.<br />

Interacti<strong>on</strong> between smugglers is mostly<br />

<strong>on</strong>e <strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>e. �ere is no s<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>gle masterm<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>d who fully<br />

c<strong>on</strong>trols the smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g process.

C84,;@(.7;82270>/1,805(98.(,2D.8?,0-(<br />

7?,>70;7E6/57>(-7<br />

1) Ensure adherence of all Bali Process member<br />

states to the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress<br />

<strong>and</strong> Punish Tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pers<strong>on</strong>s, Especially<br />

Women <strong>and</strong> Children <strong>and</strong> the Protocol<br />

aga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>st <str<strong>on</strong>g>Smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g</str<strong>on</strong>g> of <str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g>s by L<strong>and</strong>,<br />

Sea <strong>and</strong> Air, both supplement<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the <str<strong>on</strong>g>United</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Nati<strong>on</strong>s</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>venti<strong>on</strong> aga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>st Transnati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Organized <strong>Crime</strong>, <strong>and</strong> their e�ective implementati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

�ese Protocols provide the �rst<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ternati<strong>on</strong>ally accepted de�niti<strong>on</strong>s of human<br />

tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> are the<br />

primary <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ternati<strong>on</strong>al legal <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>struments address<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

these crim<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>al activities.<br />

2) Ensure that e�orts to combat migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g<br />

are comprehensive (address<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g protecti<strong>on</strong><br />

needs al<strong>on</strong>gside crim<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>al justice <strong>and</strong><br />

migrati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>trol imperatives), collaborative<br />

(ideally regi<strong>on</strong>al) <strong>and</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sistent – as noted <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

the co-chairpers<strong>on</strong>s’ statement from the Fourth<br />

Bali Process Regi<strong>on</strong>al M<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>isterial C<strong>on</strong>ference <strong>on</strong><br />

People <str<strong>on</strong>g>Smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Tra�ck<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pers<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong><br />

Related Transnati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>Crime</strong>.<br />

3) Underp<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the regi<strong>on</strong>al e�orts to combat migrant<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g with a str<strong>on</strong>g knowledge<br />

base, draw<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>on</strong> relevant <strong>and</strong> reliable <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Policy development <strong>and</strong> implementati<strong>on</strong><br />

both need to be based <strong>on</strong> evidence.<br />

4) Develop research projects that focus <strong>on</strong>:<br />

a) Identify<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> analyz<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g sub-types of migrant<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g (typologies);<br />

b) Identify<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> analyz<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g characteristics<br />

of those <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>volved <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> perpetuat<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g migrant<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g (the smugglers);<br />

c) Identify<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>and</strong> analyz<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g characteristics,<br />

motivati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>and</strong> experiences (positive<br />

<strong>and</strong> negative) of the customers of migrant<br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g (migrants);<br />

d) Clarify<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the size of irregular migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

�ows <strong>and</strong> to what extent they are facilitated<br />

<strong>and</strong> motivated by migrant smuggler;<br />

e) Assess<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g the impact <strong>and</strong> e�ectiveness of<br />

resp<strong>on</strong>ses to migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g.<br />

!#70'4&%*8#9':*';#$

12<br />

2*-.&"%#345--,*"-#*"#!6*&<br />

:8301.@(),13/1,80(F?7.?,7=<br />

Aga<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>st the backdrop of an uneven, sketchy <strong>and</strong> limited<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> base, the follow<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g part summarizes<br />

the available <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>formati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>ta<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>ed <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> the 14 country<br />

chapters:<br />

South-West <str<strong>on</strong>g>Asia</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Afghanistan<br />

�ere are <strong>on</strong>ly a few dedicated, empirically based research<br />

reports that c<strong>on</strong>tribute any underst<strong>and</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g <strong>on</strong><br />

the smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g of Afghan citizens. �e reviewed literature,<br />

however, does not <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>clude any comprehensive<br />

data <strong>on</strong> migrant smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g or irregular migrati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Accord<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g to the reviewed literature:<br />

�� Irregular migrati<strong>on</strong> of Afghan citizens is<br />

largely facilitated by migrant smugglers –<br />

with the excepti<strong>on</strong> of enter<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g Pakistan <strong>and</strong> the<br />

Islamic Republic of Iran from Afghanistan due<br />

to the porous border with those countries. <str<strong>on</strong>g>Migrant</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

smuggl<str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g>g networks are based <str<strong>on</strong>g>in</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pakistan<br />

<strong>and</strong> the Islamic Republic of Iran, which are the<br />