WAR IN THE HELLENISTIC WORLD

WAR IN THE HELLENISTIC WORLD

WAR IN THE HELLENISTIC WORLD

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

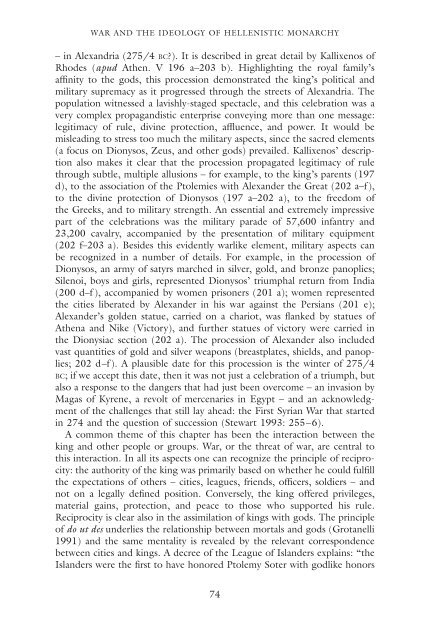

<strong>WAR</strong> AND <strong>THE</strong> IDEOLOGY OF <strong>HELLENISTIC</strong> MONARCHY<br />

– in Alexandria (275/4 BC?). It is described in great detail by Kallixenos of<br />

Rhodes (apud Athen. V 196 a–203 b). Highlighting the royal family’s<br />

affinity to the gods, this procession demonstrated the king’s political and<br />

military supremacy as it progressed through the streets of Alexandria. The<br />

population witnessed a lavishly-staged spectacle, and this celebration was a<br />

very complex propagandistic enterprise conveying more than one message:<br />

legitimacy of rule, divine protection, affluence, and power. It would be<br />

misleading to stress too much the military aspects, since the sacred elements<br />

(a focus on Dionysos, Zeus, and other gods) prevailed. Kallixenos’ description<br />

also makes it clear that the procession propagated legitimacy of rule<br />

through subtle, multiple allusions – for example, to the king’s parents (197<br />

d), to the association of the Ptolemies with Alexander the Great (202 a–f),<br />

to the divine protection of Dionysos (197 a–202 a), to the freedom of<br />

the Greeks, and to military strength. An essential and extremely impressive<br />

part of the celebrations was the military parade of 57,600 infantry and<br />

23,200 cavalry, accompanied by the presentation of military equipment<br />

(202 f–203 a). Besides this evidently warlike element, military aspects can<br />

be recognized in a number of details. For example, in the procession of<br />

Dionysos, an army of satyrs marched in silver, gold, and bronze panoplies;<br />

Silenoi, boys and girls, represented Dionysos’ triumphal return from India<br />

(200 d–f ), accompanied by women prisoners (201 a); women represented<br />

the cities liberated by Alexander in his war against the Persians (201 e);<br />

Alexander’s golden statue, carried on a chariot, was flanked by statues of<br />

Athena and Nike (Victory), and further statues of victory were carried in<br />

the Dionysiac section (202 a). The procession of Alexander also included<br />

vast quantities of gold and silver weapons (breastplates, shields, and panoplies;<br />

202 d–f). A plausible date for this procession is the winter of 275/4<br />

BC; if we accept this date, then it was not just a celebration of a triumph, but<br />

also a response to the dangers that had just been overcome – an invasion by<br />

Magas of Kyrene, a revolt of mercenaries in Egypt – and an acknowledgment<br />

of the challenges that still lay ahead: the First Syrian War that started<br />

in 274 and the question of succession (Stewart 1993: 255–6).<br />

A common theme of this chapter has been the interaction between the<br />

king and other people or groups. War, or the threat of war, are central to<br />

this interaction. In all its aspects one can recognize the principle of reciprocity:<br />

the authority of the king was primarily based on whether he could fulfill<br />

the expectations of others – cities, leagues, friends, officers, soldiers – and<br />

not on a legally defined position. Conversely, the king offered privileges,<br />

material gains, protection, and peace to those who supported his rule.<br />

Reciprocity is clear also in the assimilation of kings with gods. The principle<br />

of do ut des underlies the relationship between mortals and gods (Grotanelli<br />

1991) and the same mentality is revealed by the relevant correspondence<br />

between cities and kings. A decree of the League of Islanders explains: “the<br />

Islanders were the first to have honored Ptolemy Soter with godlike honors<br />

74