Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> Human Portrait<br />

Portraiture is deeply embedded <strong>in</strong> human culture.<br />

When view<strong>in</strong>g a human portrait, we reflexively<br />

project imag<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gs <strong>of</strong> personality onto the subject<br />

portrayed. We “see” characteristics like wisdom,<br />

vulnerability, power, glamour, and so forth,<br />

depend<strong>in</strong>g on the particular portrait. <strong>The</strong> portrait<br />

has been used over the ages as a powerful<br />

propaganda tool. From the sculpted portraits <strong>of</strong><br />

Roman emperors, to the recent, and now<br />

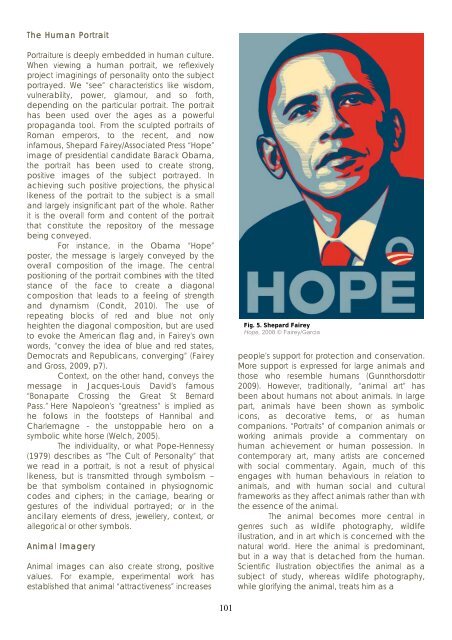

<strong>in</strong>famous, Shepard Fairey/Associated Press “Hope”<br />

image <strong>of</strong> presidential candidate Barack Obama,<br />

the portrait has been used to create strong,<br />

positive images <strong>of</strong> the subject portrayed. In<br />

achiev<strong>in</strong>g such positive projections, the physical<br />

likeness <strong>of</strong> the portrait to the subject is a small<br />

and largely <strong>in</strong>significant part <strong>of</strong> the whole. Rather<br />

it is the overall form and content <strong>of</strong> the portrait<br />

that constitute the repository <strong>of</strong> the message<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g conveyed.<br />

For <strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>in</strong> the Obama “Hope”<br />

poster, the message is largely conveyed by the<br />

overall composition <strong>of</strong> the image. <strong>The</strong> central<br />

position<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the portrait comb<strong>in</strong>es with the tilted<br />

stance <strong>of</strong> the face to create a diagonal<br />

composition that leads to a feel<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> strength<br />

and dynamism (Condit, 2010). <strong>The</strong> use <strong>of</strong><br />

repeat<strong>in</strong>g blocks <strong>of</strong> red and blue not only<br />

heighten the diagonal composition, but are used<br />

to evoke the American flag and, <strong>in</strong> Fairey’s own<br />

words, “convey the idea <strong>of</strong> blue and red states,<br />

Democrats and Republicans, converg<strong>in</strong>g” (Fairey<br />

and Gross, 2009, p7).<br />

Context, on the other hand, conveys the<br />

message <strong>in</strong> Jacques-Louis David’s famous<br />

“Bonaparte Cross<strong>in</strong>g the Great St Bernard<br />

Pass.” Here Napoleon’s “greatness” is implied as<br />

he follows <strong>in</strong> the footsteps <strong>of</strong> Hannibal and<br />

Charlemagne - the unstoppable hero on a<br />

symbolic white horse (Welch, 2005).<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuality, or what Pope-Hennessy<br />

(1979) describes as “<strong>The</strong> Cult <strong>of</strong> Personality” that<br />

we read <strong>in</strong> a portrait, is not a result <strong>of</strong> physical<br />

likeness, but is transmitted through symbolism –<br />

be that symbolism conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> physiognomic<br />

codes and ciphers; <strong>in</strong> the carriage, bear<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

gestures <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dividual portrayed; or <strong>in</strong> the<br />

ancillary elements <strong>of</strong> dress, jewellery, context, or<br />

allegorical or other symbols.<br />

Animal Imagery<br />

Animal images can also create strong, positive<br />

values. For example, experimental work has<br />

established that animal “attractiveness” <strong>in</strong>creases<br />

101<br />

Fig. 5. Shepard Fairey<br />

Hope, 2008 Fairey/Garcia<br />

people’s support for protection and conservation.<br />

More support is expressed for large animals and<br />

those who resemble humans (Gunnthorsdottir<br />

2009). However, traditionally, “animal art” has<br />

been about humans not about animals. In large<br />

part, animals have been shown as symbolic<br />

icons, as decorative items, or as human<br />

companions. “Portraits” <strong>of</strong> companion animals or<br />

work<strong>in</strong>g animals provide a commentary on<br />

human achievement or human possession. In<br />

contemporary art, many artists are concerned<br />

with social commentary. Aga<strong>in</strong>, much <strong>of</strong> this<br />

engages with human behaviours <strong>in</strong> relation to<br />

animals, and with human social and cultural<br />

frameworks as they affect animals rather than with<br />

the essence <strong>of</strong> the animal.<br />

<strong>The</strong> animal becomes more central <strong>in</strong><br />

genres such as wildlife photography, wildlife<br />

illustration, and <strong>in</strong> art which is concerned with the<br />

natural world. Here the animal is predom<strong>in</strong>ant,<br />

but <strong>in</strong> a way that is detached from the human.<br />

Scientific illustration objectifies the animal as a<br />

subject <strong>of</strong> study, whereas wildlife photography,<br />

while glorify<strong>in</strong>g the animal, treats him as a