Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Marketing Animals - Antennae The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

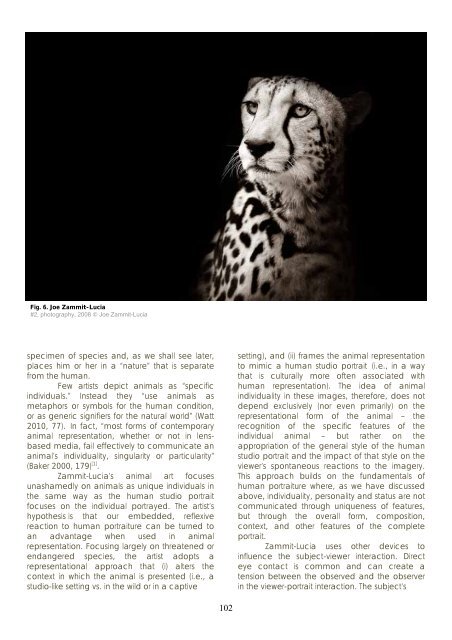

Fig. 6. Joe Zammit-Lucia<br />

#2, photography, 2008 Joe Zammit-Lucia<br />

specimen <strong>of</strong> species and, as we shall see later,<br />

places him or her <strong>in</strong> a “nature” that is separate<br />

from the human.<br />

Few artists depict animals as “specific<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuals.” Instead they “use animals as<br />

metaphors or symbols for the human condition,<br />

or as generic signifiers for the natural world” (Watt<br />

2010, 77). In fact, “most forms <strong>of</strong> contemporary<br />

animal representation, whether or not <strong>in</strong> lensbased<br />

media, fail effectively to communicate an<br />

animal’s <strong>in</strong>dividuality, s<strong>in</strong>gularity or particularity”<br />

(Baker 2000, 179) [1] .<br />

Zammit-Lucia’s animal art focuses<br />

unashamedly on animals as unique <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong><br />

the same way as the human studio portrait<br />

focuses on the <strong>in</strong>dividual portrayed. <strong>The</strong> artist’s<br />

hypothesis is that our embedded, reflexive<br />

reaction to human portraiture can be turned to<br />

an advantage when used <strong>in</strong> animal<br />

representation. Focus<strong>in</strong>g largely on threatened or<br />

endangered species, the artist adopts a<br />

representational approach that (i) alters the<br />

context <strong>in</strong> which the animal is presented (i.e., a<br />

studio-like sett<strong>in</strong>g vs. <strong>in</strong> the wild or <strong>in</strong> a captive<br />

102<br />

sett<strong>in</strong>g), and (ii) frames the animal representation<br />

to mimic a human studio portrait (i.e., <strong>in</strong> a way<br />

that is culturally more <strong>of</strong>ten associated with<br />

human representation). <strong>The</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> animal<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividuality <strong>in</strong> these images, therefore, does not<br />

depend exclusively (nor even primarily) on the<br />

representational form <strong>of</strong> the animal – the<br />

recognition <strong>of</strong> the specific features <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual animal – but rather on the<br />

appropriation <strong>of</strong> the general style <strong>of</strong> the human<br />

studio portrait and the impact <strong>of</strong> that style on the<br />

viewer’s spontaneous reactions to the imagery.<br />

This approach builds on the fundamentals <strong>of</strong><br />

human portraiture where, as we have discussed<br />

above, <strong>in</strong>dividuality, personality and status are not<br />

communicated through uniqueness <strong>of</strong> features,<br />

but through the overall form, composition,<br />

context, and other features <strong>of</strong> the complete<br />

portrait.<br />

Zammit-Lucia uses other devices to<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence the subject-viewer <strong>in</strong>teraction. Direct<br />

eye contact is common and can create a<br />

tension between the observed and the observer<br />

<strong>in</strong> the viewer-portrait <strong>in</strong>teraction. <strong>The</strong> subject’s