Download - GRaBS

Download - GRaBS

Download - GRaBS

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

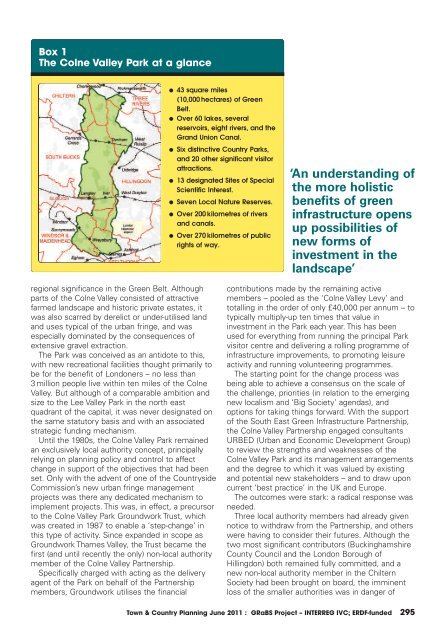

Box 1<br />

The Colne Valley Park at a glance<br />

● 43 square miles<br />

(10,000 hectares) of Green<br />

Belt.<br />

● Over 60 lakes, several<br />

reservoirs, eight rivers, and the<br />

Grand Union Canal.<br />

● Six distinctive Country Parks,<br />

and 20 other significant visitor<br />

attractions.<br />

● 13 designated Sites of Special<br />

Scientific Interest.<br />

● Seven Local Nature Reserves.<br />

● Over 200 kilometres of rivers<br />

and canals.<br />

● Over 270 kilometres of public<br />

rights of way.<br />

‘An understanding of<br />

the more holistic<br />

benefits of green<br />

infrastructure opens<br />

up possibilities of<br />

new forms of<br />

investment in the<br />

landscape’<br />

regional significance in the Green Belt. Although<br />

parts of the Colne Valley consisted of attractive<br />

farmed landscape and historic private estates, it<br />

was also scarred by derelict or under-utilised land<br />

and uses typical of the urban fringe, and was<br />

especially dominated by the consequences of<br />

extensive gravel extraction.<br />

The Park was conceived as an antidote to this,<br />

with new recreational facilities thought primarily to<br />

be for the benefit of Londoners – no less than<br />

3 million people live within ten miles of the Colne<br />

Valley. But although of a comparable ambition and<br />

size to the Lee Valley Park in the north east<br />

quadrant of the capital, it was never designated on<br />

the same statutory basis and with an associated<br />

strategic funding mechanism.<br />

Until the 1980s, the Colne Valley Park remained<br />

an exclusively local authority concept, principally<br />

relying on planning policy and control to affect<br />

change in support of the objectives that had been<br />

set. Only with the advent of one of the Countryside<br />

Commission’s new urban fringe management<br />

projects was there any dedicated mechanism to<br />

implement projects. This was, in effect, a precursor<br />

to the Colne Valley Park Groundwork Trust, which<br />

was created in 1987 to enable a ‘step-change’ in<br />

this type of activity. Since expanded in scope as<br />

Groundwork Thames Valley, the Trust became the<br />

first (and until recently the only) non-local authority<br />

member of the Colne Valley Partnership.<br />

Specifically charged with acting as the delivery<br />

agent of the Park on behalf of the Partnership<br />

members, Groundwork utilises the financial<br />

contributions made by the remaining active<br />

members – pooled as the ‘Colne Valley Levy’ and<br />

totalling in the order of only £40,000 per annum – to<br />

typically multiply-up ten times that value in<br />

investment in the Park each year. This has been<br />

used for everything from running the principal Park<br />

visitor centre and delivering a rolling programme of<br />

infrastructure improvements, to promoting leisure<br />

activity and running volunteering programmes.<br />

The starting point for the change process was<br />

being able to achieve a consensus on the scale of<br />

the challenge, priorities (in relation to the emerging<br />

new localism and ‘Big Society’ agendas), and<br />

options for taking things forward. With the support<br />

of the South East Green Infrastructure Partnership,<br />

the Colne Valley Partnership engaged consultants<br />

URBED (Urban and Economic Development Group)<br />

to review the strengths and weaknesses of the<br />

Colne Valley Park and its management arrangements<br />

and the degree to which it was valued by existing<br />

and potential new stakeholders – and to draw upon<br />

current ‘best practice’ in the UK and Europe.<br />

The outcomes were stark: a radical response was<br />

needed.<br />

Three local authority members had already given<br />

notice to withdraw from the Partnership, and others<br />

were having to consider their futures. Although the<br />

two most significant contributors (Buckinghamshire<br />

County Council and the London Borough of<br />

Hillingdon) both remained fully committed, and a<br />

new non-local authority member in the Chiltern<br />

Society had been brought on board, the imminent<br />

loss of the smaller authorities was in danger of<br />

Town & Country Planning June 2011 : <strong>GRaBS</strong> Project – INTERREG IVC; ERDF-funded 295