Artist's Book Yearbook 2003-2005 - Book Arts - University of the ...

Artist's Book Yearbook 2003-2005 - Book Arts - University of the ...

Artist's Book Yearbook 2003-2005 - Book Arts - University of the ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Size Matters<br />

Dr Stephen Bury<br />

One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> curiosities <strong>of</strong> 2002 publishing was<br />

The Smallest <strong>Book</strong> in <strong>the</strong> World (Leipzig: Gestalten<br />

Verlag) by <strong>the</strong> German typographer, Josua<br />

Reichert – a 2.4 x 2.6 mm red lea<strong>the</strong>r bound<br />

book <strong>of</strong> 26 pages <strong>of</strong> alphabetical exercises,<br />

complete with wooden box and magnifying<br />

glass. It connotes <strong>the</strong> masterworks <strong>of</strong> medieval<br />

guild apprentices, those miniature stairs<br />

leading nowhere, tongue-and-grooved with<br />

minute precision, all form and no function,<br />

obsessive even. Why, for example, have a<br />

lea<strong>the</strong>r cover at all when it could not possibly<br />

protect <strong>the</strong> contents? Contrast this with Irene<br />

Chan’s The <strong>Book</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World (Ch’An Press,<br />

2000). At 1” by 1” it is not as small as Reichert’s.<br />

Nor does it claim <strong>the</strong> title <strong>of</strong> ‘smallest’: in fact,<br />

<strong>the</strong> contrast <strong>of</strong> titles is suggestive – Reichert’s<br />

book is <strong>the</strong> smallest in <strong>the</strong> world (at least for<br />

<strong>the</strong> moment), whilst Chan’s book is ‘<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

world’ i.e. <strong>the</strong> whole world is contained in <strong>the</strong><br />

book. Chan’s point <strong>of</strong> departure is John<br />

Dalton’s metaphor in his book on atomic<br />

<strong>the</strong>ory, A New System <strong>of</strong> Chemical Philosophy<br />

(1808), in which he compares molecules and<br />

atoms to words and letters. The <strong>Book</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> World<br />

extends this comparison, both <strong>the</strong> 26 letters <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Roman alphabet and <strong>the</strong> 90 atoms are<br />

combinable to make words and molecules, but<br />

not all combinations are permitted. A silver<br />

leperello structure holds <strong>the</strong> text, which<br />

surmounts images on transparent paper <strong>of</strong><br />

Dalton’s ‘elastic fluid’ and gas. Both are<br />

contained in a ‘bug box’, <strong>the</strong> naturalist’s small<br />

clear container for samples – ants, moths,<br />

beetles etc. – with <strong>the</strong> lid’s convex lens acting as<br />

an inbuilt magnifying glass. This is multum in<br />

parvo, <strong>the</strong> world in a grain <strong>of</strong> sand. The natural<br />

world and <strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> imagination (where<br />

<strong>the</strong> reader can forget him/herself in <strong>the</strong><br />

world/s created by <strong>the</strong> author toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong><br />

reader) are continuously substituted one for<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r. The simplicity in idea and execution<br />

<strong>of</strong> Chan’s project stands in stark contrast to <strong>the</strong><br />

literally overwrought graphic design <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

so-called smallest book in <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

Paradoxically, larger books are smaller. This<br />

may require some explanation. When I taught<br />

47<br />

an artists’ books workshop at Chelsea School <strong>of</strong><br />

Art, I used to suggest that most things in <strong>the</strong><br />

seminar room could be made into a book – <strong>the</strong><br />

Venetian blinds, <strong>the</strong> doors etc. The Fluxus artist<br />

and who was also closely involved with Dick<br />

Higgins’s Something Else Press, Alison Knowles<br />

constructed The Big <strong>Book</strong> (1966-8). This had 7<br />

pages (including a fold-out one), a spine, a<br />

copyright notice etc. - some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> defining<br />

qualities <strong>of</strong> ‘a book’. But it was 8 feet tall, had a<br />

table, telephone line and a grass tunnel to<br />

sleep in, and it was meant to be a functional<br />

living space. Our expectations <strong>of</strong> intimacy and<br />

privacy from <strong>the</strong> bedroom or home are<br />

undermined, subverted in this public,<br />

transparent and collapsible (it literally did so<br />

on tour in California) space/book.<br />

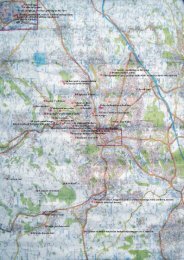

O<strong>the</strong>rs have attempted an (almost) one-to-one<br />

scale matching <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> book to <strong>the</strong> world, or <strong>the</strong><br />

world to <strong>the</strong> book . Herr Mein in Lewis<br />

Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno concluded, first<br />

published in 1893 boasts <strong>of</strong> his map on <strong>the</strong><br />

scale <strong>of</strong> a mile to a mile: “It has never been<br />

spread out, yet. The farmers objected: <strong>the</strong>y said<br />

it would cover <strong>the</strong> whole country, and shut out<br />

<strong>the</strong> sunlight! So we now use <strong>the</strong> country itself,<br />

as its own map…it does nearly as well.” I am<br />

also reminded <strong>of</strong> John Ruskin’s Examples, a<br />

separately published illustrated appendix to<br />

The Stones <strong>of</strong> Venice, double elephant folio sized<br />

etchings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ‘details’ <strong>of</strong> columns and facades<br />

<strong>of</strong> Venetian palazzi and churches – in fact<br />

‘details’ is probably <strong>the</strong> wrong word, as <strong>the</strong>y are<br />

life-size, <strong>the</strong> transference <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Venetian<br />

city-scape, one by one, into a doomed book<br />

project.<br />

This literal translation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> world into book<br />

underlies <strong>the</strong> 1966 project by Anthony<br />

Earnshaw, Patrick Hughes, Swift and Page. The<br />

450 ‘leaves’ <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> book, The Sycamore Tree, in an<br />

edition <strong>of</strong> four, consist <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> impressions <strong>of</strong><br />

leaves from a specific sycamore tree in Leeds,<br />

10-14 August 1966. Similarly, Herman de Vries<br />

16m_: an essay (Bern: Lydia Megert, 1979), in<br />

an edition <strong>of</strong> 50, takes that area <strong>of</strong> ground and<br />

maps <strong>the</strong> findings and samples from different<br />

spots. All <strong>the</strong>se projects suggest that this<br />

attempt to equate in a literal one to one way<br />

<strong>the</strong> world and <strong>the</strong> book can only ever be<br />

fragmentary: this type <strong>of</strong> ‘big book’ <strong>the</strong>refore<br />

being potentially smaller than <strong>the</strong> little book.