Space Acquisition - Air Force Space Command

Space Acquisition - Air Force Space Command

Space Acquisition - Air Force Space Command

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

difference: public policy created the space industrial<br />

base and strongly influences its development. But it<br />

cannot make all the difference that was desired, and evidently<br />

it made some differences that were not desired.<br />

As reported by the Young panel in 2003, space acquisition<br />

suffered from systemic pathologies:<br />

• “Cost has replaced mission success as the primary<br />

driver in management acquisition processes,<br />

resulting in excessive technical and schedule<br />

risk.”<br />

• “The space acquisition system is strongly biased<br />

to produce unrealistically low cost estimates<br />

throughout the acquisition process. These estimates<br />

lead to unrealistic budgets and unexecutable<br />

programs.”<br />

• “Government capabilities to lead and manage the acquisition<br />

process have seriously eroded.”<br />

• “While the space industrial base is adequate to support<br />

current programs, long-term concerns exist. A continuous<br />

flow of new programs—cautiously selected—is required<br />

to maintain a robust space industry. Without such a flow,<br />

we risk not only our workforce, but also critical national<br />

capabilities in the payload and sensor areas.” 5<br />

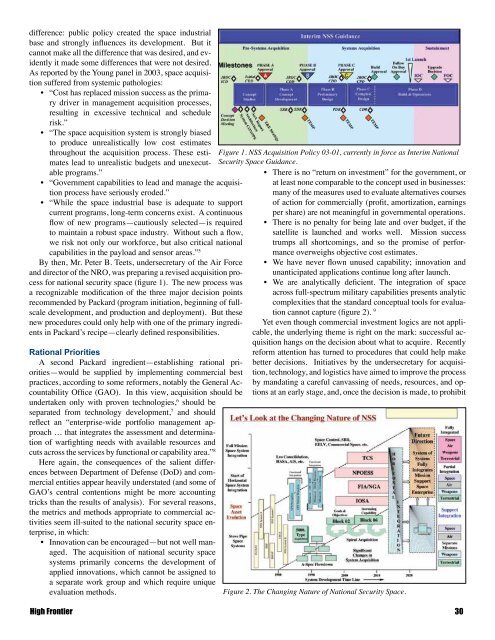

By then, Mr. Peter B. Teets, undersecretary of the <strong>Air</strong> <strong>Force</strong><br />

and director of the NRO, was preparing a revised acquisition process<br />

for national security space (figure 1). The new process was<br />

a recognizable modification of the three major decision points<br />

recommended by Packard (program initiation, beginning of fullscale<br />

development, and production and deployment). But these<br />

new procedures could only help with one of the primary ingredients<br />

in Packard’s recipe—clearly defined responsibilities.<br />

Rational Priorities<br />

A second Packard ingredient—establishing rational priorities—would<br />

be supplied by implementing commercial best<br />

practices, according to some reformers, notably the General Accountability<br />

Office (GAO). In this view, acquisition should be<br />

undertaken only with proven technologies, 6 should be<br />

separated from technology development, 7 and should<br />

reflect an “enterprise-wide portfolio management approach<br />

… that integrates the assessment and determination<br />

of warfighting needs with available resources and<br />

cuts across the services by functional or capability area.” 8<br />

Here again, the consequences of the salient differences<br />

between Department of Defense (DoD) and commercial<br />

entities appear heavily understated (and some of<br />

GAO’s central contentions might be more accounting<br />

tricks than the results of analysis). For several reasons,<br />

the metrics and methods appropriate to commercial activities<br />

seem ill-suited to the national security space enterprise,<br />

in which:<br />

• Innovation can be encouraged—but not well managed.<br />

The acquisition of national security space<br />

systems primarily concerns the development of<br />

applied innovations, which cannot be assigned to<br />

a separate work group and which require unique<br />

evaluation methods.<br />

Figure 1. NSS <strong>Acquisition</strong> Policy 03-01, currently in force as Interim National<br />

Security <strong>Space</strong> Guidance.<br />

• There is no “return on investment” for the government, or<br />

at least none comparable to the concept used in businesses:<br />

many of the measures used to evaluate alternatives courses<br />

of action for commercially (profit, amortization, earnings<br />

per share) are not meaningful in governmental operations.<br />

• There is no penalty for being late and over budget, if the<br />

satellite is launched and works well. Mission success<br />

trumps all shortcomings, and so the promise of performance<br />

overweighs objective cost estimates.<br />

• We have never flown unused capability; innovation and<br />

unanticipated applications continue long after launch.<br />

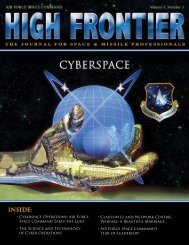

• We are analytically deficient. The integration of space<br />

across full-spectrum military capabilities presents analytic<br />

complexities that the standard conceptual tools for evaluation<br />

cannot capture (figure 2). 9<br />

Yet even though commercial investment logics are not applicable,<br />

the underlying theme is right on the mark: successful acquisition<br />

hangs on the decision about what to acquire. Recently<br />

reform attention has turned to procedures that could help make<br />

better decisions. Initiatives by the undersecretary for acquisition,<br />

technology, and logistics have aimed to improve the process<br />

by mandating a careful canvassing of needs, resources, and options<br />

at an early stage, and, once the decision is made, to prohibit<br />

Figure 2. The Changing Nature of National Security <strong>Space</strong>.<br />

High Frontier 30