Following Odysseus Not the end of the world Amarna city of light ...

Following Odysseus Not the end of the world Amarna city of light ...

Following Odysseus Not the end of the world Amarna city of light ...

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

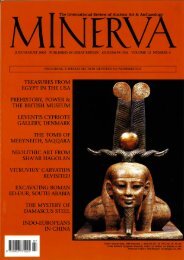

in<strong>the</strong>newsLost Roman town resurfacesHaving lain dormant for 1,500 years, <strong>the</strong>town <strong>of</strong> Interamna Lirenas, 50 miles south<strong>of</strong> Rome, has been rediscovered and ischanging scholars’ view <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong>Roman colonial settlements.Long known about from <strong>the</strong> writings <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Roman historian Livy and <strong>the</strong> Greekgeographer Strabo, Interamna Lirenas hadalways been seen as a quiet town <strong>of</strong> littleconsequence, which followed <strong>the</strong> standardtemplate <strong>of</strong> urban development. But <strong>the</strong>recent work <strong>of</strong> a collaborative projectinvolving Cambridge University, <strong>the</strong> BritishSchool at Rome, <strong>the</strong> British Academy and<strong>the</strong> Italian State Archaeological Service hasshed more <strong>light</strong> on this supposed backwater.The exact location <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> town, in <strong>the</strong>Liri Valley in Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Lazio, was gleanedfrom ancient sources. The fact that it wasstill unexcavated, and was thought tohave developed relatively little during <strong>the</strong>Imperial Roman era, made <strong>the</strong> town anideal candidate to accurately reflectoriginal colonial settlement features.Led by Martin Millett, LaurencePr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Classical Archaeology atCambridge and Fellow <strong>of</strong> FitzwilliamCollege, and Dr Alessandro Launaro,Postdoctoral Fellow at <strong>the</strong> British Academyand Fellow <strong>of</strong> Darwin College, <strong>the</strong> teamknew that a full-scale excavation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>site, which covers more than 25 hectares,would be impractical, so <strong>the</strong>y started withgeophysical mapping.By using a combination <strong>of</strong> scientifictechniques – ground-penetrating radar andmagnetometry – <strong>the</strong> team began to buildup a picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> original street plan, andspecific features came to <strong>the</strong> fore.The greatest surprise was <strong>the</strong> appearance<strong>of</strong> a building with radially arranged wallsand tiered seats within, which soonrevealed itself to be a Roman <strong>the</strong>atre.This suddenly changed <strong>the</strong> perception<strong>of</strong> this town as a small settlement.With its dominant temple and forum,Interamna Lirenas distinguishes itselfconsiderably from nearby Fregellae,which is also on <strong>the</strong> Via Latina – <strong>the</strong>principal road leading south-east out <strong>of</strong>Rome – and which was previously thoughtto be a comparable colonial town.Millett explained <strong>the</strong> significance <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>find: it challenges <strong>the</strong> formerly held viewthat Rome projected a certain image <strong>of</strong>itself by building all colonial towns to apattern, and hence organising what <strong>the</strong>communities’ priorities would be, a viewthis discovery now challenges.There are hopes that excavation maybegin again in earnest in summer 2013,starting with <strong>the</strong> nor<strong>the</strong>rn corner, whichincorporates <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre and <strong>the</strong> forum,this would hopefully allow <strong>the</strong> precisedating <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se structures. The local mayorhopes to turn what is know an unassumingstretch <strong>of</strong> farmland into an archaeologicalpark in <strong>the</strong> future.Ge<strong>of</strong>f LowsleyDental detritus reveals useful factsThe idea <strong>of</strong> picking throughsomeone else’s dental detrituswould fill most <strong>of</strong> us withhorror, but it is by doing exactlythis that Christina Warriner,<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Centre for EvolutionaryMedicine at <strong>the</strong> University<strong>of</strong> Zurich, is gleaning valuableinformation about <strong>the</strong> lives<strong>of</strong> Iranian miners who died2,000 years ago.Archaeological geneticistsstudy some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> more unusualelements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> material remains<strong>of</strong> our ancestors to gain aninsight into <strong>the</strong> past. Fromanimal, plant and bacterialremains to human tissue, boneand teeth, all <strong>the</strong> biomoleculesleft in what was once livingcan pass down a vast amount<strong>of</strong> information about <strong>the</strong>surrounding environment.Warriner explained howmillions <strong>of</strong> threads <strong>of</strong> DNAbelonging to bacteria thatinhabited <strong>the</strong> mouth and throatare captured in dental calculus(commonly called plaque).Extracting and examining<strong>the</strong>se DNA threads should‘allow us to investigate <strong>the</strong>long-term evolutionary history<strong>of</strong> human health and disease,right down to <strong>the</strong> genetic code<strong>of</strong> individual pathogens, and itshould allow us to reconstruct adetailed picture <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dynamicinterplay between diet, infectionand immunity that occurredthousands <strong>of</strong> years ago’.Her particular area <strong>of</strong> interestis <strong>the</strong> mummies <strong>of</strong> miners from<strong>the</strong> salt mines <strong>of</strong> Chehr Abad,in north-west Iran, dating from<strong>the</strong> 4th century BC to <strong>the</strong> 4thcentury AD. The bodies <strong>of</strong> menwere naturally preserved bydesiccation when <strong>the</strong> salt minescollapsed. Unlike Egyptianmummies, <strong>the</strong>y did not have<strong>the</strong>ir organs removed and,incredibly, some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tissueis still intact.The aim <strong>of</strong> her project is t<strong>of</strong>ind evidence for an inheritedgenetic trait, a deficiency in<strong>the</strong> enzyme G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase),which causes anaemia, aparticularly common conditionin modern-day Iran.It has been postulated thatmany <strong>of</strong> today’s digestivedisorders may be precipitatedby modern food-productiontechniques causing an imbalancein <strong>the</strong> bacteria within <strong>the</strong> gut.It is possible that identifying <strong>the</strong>bacteria carried by our ancestorscould help to determine what isa healthy balance.This type <strong>of</strong> study need not belimited to digestive conditions,however. Warriner explains:‘Diseases and disorders such asperiodontitis, heart disease,allergies and diabetes all have anevolutionary component relatedto <strong>the</strong> fact that we live in adifferent environment to <strong>the</strong> onein which our bodies evolved.’So we may also learn valuablelessons that can help in modernmedical treatment.While dentists tell us to brushour teeth regularly, we arefortunate that those before uswere not schooled in dentalhygiene, as we now have thisinvaluable archaeologicalrecord written in <strong>the</strong>ir plaque.Ge<strong>of</strong>f LowsleyChristina Warriner examines amandible showing dental calculusand ante-mortem tooth loss in aDNA clean labcourtesy <strong>of</strong> Christina Warinner4