Ecology and Management of Avian Botulism on the Canadian Prairies

Ecology and Management of Avian Botulism on the Canadian Prairies

Ecology and Management of Avian Botulism on the Canadian Prairies

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

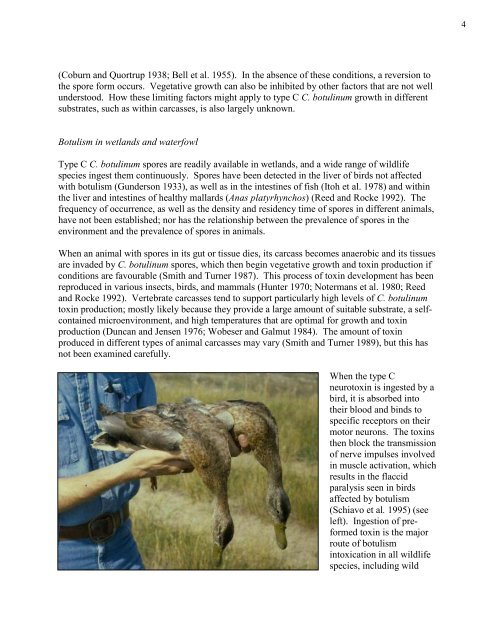

4(Coburn <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Quortrup 1938; Bell et al. 1955). In <strong>the</strong> absence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong>se c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, a reversi<strong>on</strong> to<strong>the</strong> spore form occurs. Vegetative growth can also be inhibited by o<strong>the</strong>r factors that are not wellunderstood. How <strong>the</strong>se limiting factors might apply to type C C. botulinum growth in differentsubstrates, such as within carcasses, is also largely unknown.<str<strong>on</strong>g>Botulism</str<strong>on</strong>g> in wetl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> waterfowlType C C. botulinum spores are readily available in wetl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> a wide range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> wildlifespecies ingest <strong>the</strong>m c<strong>on</strong>tinuously. Spores have been detected in <strong>the</strong> liver <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds not affectedwith botulism (Gunders<strong>on</strong> 1933), as well as in <strong>the</strong> intestines <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> fish (Itoh et al. 1978) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> within<strong>the</strong> liver <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> intestines <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> healthy mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) (Reed <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rocke 1992). Thefrequency <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> occurrence, as well as <strong>the</strong> density <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> residency time <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> spores in different animals,have not been established; nor has <strong>the</strong> relati<strong>on</strong>ship between <strong>the</strong> prevalence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> spores in <strong>the</strong>envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>the</strong> prevalence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> spores in animals.When an animal with spores in its gut or tissue dies, its carcass becomes anaerobic <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> its tissuesare invaded by C. botulinum spores, which <strong>the</strong>n begin vegetative growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> toxin producti<strong>on</strong> ifc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s are favourable (Smith <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Turner 1987). This process <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> toxin development has beenreproduced in various insects, birds, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> mammals (Hunter 1970; Notermans et al. 1980; Reed<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rocke 1992). Vertebrate carcasses tend to support particularly high levels <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> C. botulinumtoxin producti<strong>on</strong>; mostly likely because <strong>the</strong>y provide a large amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> suitable substrate, a selfc<strong>on</strong>tainedmicroenvir<strong>on</strong>ment, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> high temperatures that are optimal for growth <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> toxinproducti<strong>on</strong> (Duncan <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Jensen 1976; Wobeser <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Galmut 1984). The amount <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> toxinproduced in different types <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal carcasses may vary (Smith <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Turner 1989), but this hasnot been examined carefully.When <strong>the</strong> type Cneurotoxin is ingested by abird, it is absorbed into<strong>the</strong>ir blood <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> binds tospecific receptors <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>irmotor neur<strong>on</strong>s. The toxins<strong>the</strong>n block <strong>the</strong> transmissi<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> nerve impulses involvedin muscle activati<strong>on</strong>, whichresults in <strong>the</strong> flaccidparalysis seen in birdsaffected by botulism(Schiavo et al. 1995) (seeleft). Ingesti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> preformedtoxin is <strong>the</strong> majorroute <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> botulismintoxicati<strong>on</strong> in all wildlifespecies, including wild