Frank Thomas

Frank Thomas

Frank Thomas

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Notable Sports Figures<br />

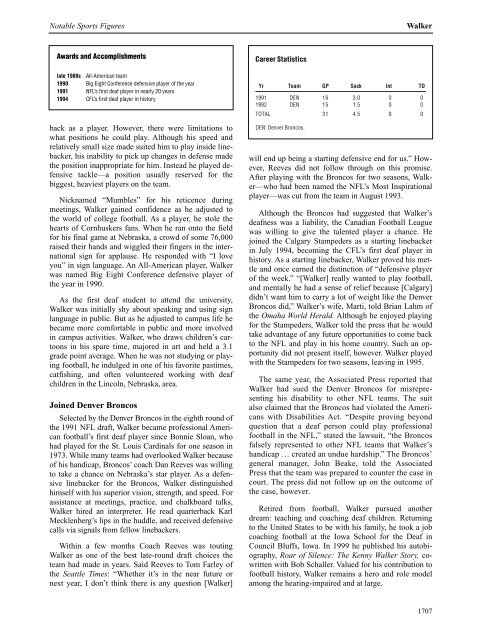

Awards and Accomplishments<br />

late 1980s All-American team<br />

1990 Big Eight Conference defensive player of the year<br />

1991 NFL’s first deaf player in nearly 20 years<br />

1994 CFL’s first deaf player in history<br />

back as a player. However, there were limitations to<br />

what positions he could play. Although his speed and<br />

relatively small size made suited him to play inside linebacker,<br />

his inability to pick up changes in defense made<br />

the position inappropriate for him. Instead he played defensive<br />

tackle—a position usually reserved for the<br />

biggest, heaviest players on the team.<br />

Nicknamed “Mumbles” for his reticence during<br />

meetings, Walker gained confidence as he adjusted to<br />

the world of college football. As a player, he stole the<br />

hearts of Cornhuskers fans. When he ran onto the field<br />

for his final game at Nebraska, a crowd of some 76,000<br />

raised their hands and wiggled their fingers in the international<br />

sign for applause. He responded with “I love<br />

you” in sign language. An All-American player, Walker<br />

was named Big Eight Conference defensive player of<br />

the year in 1990.<br />

As the first deaf student to attend the university,<br />

Walker was initially shy about speaking and using sign<br />

language in public. But as he adjusted to campus life he<br />

became more comfortable in public and more involved<br />

in campus activities. Walker, who draws children’s cartoons<br />

in his spare time, majored in art and held a 3.1<br />

grade point average. When he was not studying or playing<br />

football, he indulged in one of his favorite pastimes,<br />

catfishing, and often volunteered working with deaf<br />

children in the Lincoln, Nebraska, area.<br />

Joined Denver Broncos<br />

Selected by the Denver Broncos in the eighth round of<br />

the 1991 NFL draft, Walker became professional American<br />

football’s first deaf player since Bonnie Sloan, who<br />

had played for the St. Louis Cardinals for one season in<br />

1973. While many teams had overlooked Walker because<br />

of his handicap, Broncos’ coach Dan Reeves was willing<br />

to take a chance on Nebraska’s star player. As a defensive<br />

linebacker for the Broncos, Walker distinguished<br />

himself with his superior vision, strength, and speed. For<br />

assistance at meetings, practice, and chalkboard talks,<br />

Walker hired an interpreter. He read quarterback Karl<br />

Mecklenberg’s lips in the huddle, and received defensive<br />

calls via signals from fellow linebackers.<br />

Within a few months Coach Reeves was touting<br />

Walker as one of the best late-round draft choices the<br />

team had made in years. Said Reeves to Tom Farley of<br />

the Seattle Times: “Whether it’s in the near future or<br />

next year, I don’t think there is any question [Walker]<br />

Career Statistics<br />

Walker<br />

Yr Team GP Sack Int TD<br />

1991 DEN 16 3.0 0 0<br />

1992 DEN 15 1.5 0 0<br />

TOTAL 31 4.5 0 0<br />

DEN: Denver Broncos.<br />

will end up being a starting defensive end for us.” However,<br />

Reeves did not follow through on this promise.<br />

After playing with the Broncos for two seasons, Walker—who<br />

had been named the NFL’s Most Inspirational<br />

player—was cut from the team in August 1993.<br />

Although the Broncos had suggested that Walker’s<br />

deafness was a liability, the Canadian Football League<br />

was willing to give the talented player a chance. He<br />

joined the Calgary Stampeders as a starting linebacker<br />

in July 1994, becoming the CFL’s first deaf player in<br />

history. As a starting linebacker, Walker proved his mettle<br />

and once earned the distinction of “defensive player<br />

of the week.” “[Walker] really wanted to play football,<br />

and mentally he had a sense of relief because [Calgary]<br />

didn’t want him to carry a lot of weight like the Denver<br />

Broncos did,” Walker’s wife, Marti, told Brian Lahm of<br />

the Omaha World Herald. Although he enjoyed playing<br />

for the Stampeders, Walker told the press that he would<br />

take advantage of any future opportunities to come back<br />

to the NFL and play in his home country. Such an opportunity<br />

did not present itself, however. Walker played<br />

with the Stampeders for two seasons, leaving in 1995.<br />

The same year, the Associated Press reported that<br />

Walker had sued the Denver Broncos for misrepresenting<br />

his disability to other NFL teams. The suit<br />

also claimed that the Broncos had violated the Americans<br />

with Disabilities Act. “Despite proving beyond<br />

question that a deaf person could play professional<br />

football in the NFL,” stated the lawsuit, “the Broncos<br />

falsely represented to other NFL teams that Walker’s<br />

handicap … created an undue hardship.” The Broncos’<br />

general manager, John Beake, told the Associated<br />

Press that the team was prepared to counter the case in<br />

court. The press did not follow up on the outcome of<br />

the case, however.<br />

Retired from football, Walker pursued another<br />

dream: teaching and coaching deaf children. Returning<br />

to the United States to be with his family, he took a job<br />

coaching football at the Iowa School for the Deaf in<br />

Council Bluffs, Iowa. In 1999 he published his autobiography,<br />

Roar of Silence: The Kenny Walker Story, cowritten<br />

with Bob Schaller. Valued for his contribution to<br />

football history, Walker remains a hero and role model<br />

among the hearing-impaired and at large.<br />

1707