Frank Thomas

Frank Thomas

Frank Thomas

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Notable Sports Figures<br />

She was actually speaking the truth [that she was the<br />

greatest]. And some people probably didn’t like it at that<br />

time because it was coming from a woman.”<br />

A skilled self-promoter, Zaharias often changed her<br />

birth date, making herself appear younger than she was.<br />

This deception was intended to make her seem even<br />

more of a star than she already was—for example, on<br />

her application for the 1932 Olympics, she wrote that<br />

she was born in 1914. As Susan E. Cayleff noted in<br />

Babe: The Life and Legend of Babe Didrikson Zaharias,<br />

“If a twenty-year-old excelling at the Olympics in 1932<br />

was heralded, then an eighteen-year-old—or better yet a<br />

seventeen-year-old—might be worshipped!” Her gravestone<br />

and her baptismal certificate corroborate the earlier<br />

1911 date.<br />

In the early 1930s, Zaharias also began playing golf.<br />

By her eleventh game, in 1932, she drove the ball 260<br />

yards from the first tee and played the second set of nine<br />

holes with a score of 43. She entered her first tournament<br />

in 1934, and won the qualifying round with a score of 77.<br />

At the Texas State Women’s Championship in April of<br />

1935, she carded a birdie on the par-5 31st hole and won<br />

the tournament two-up. In 1935, she was making<br />

$15,000 a year from endorsements and golf matches.<br />

Gender Backlash<br />

Despite her success, or because of it, a backlash<br />

against her swelled up in the press and in popular opinion,<br />

fueled by her refusal to fit typical stereotypes of<br />

womanhood. According to William O. Johnson and<br />

Nancy P. Williamson in Whatta Gal: The Babe Didrikson<br />

Story, she was “seen by many reporters and members of<br />

the public as a freak . . . an aberration . . . a living putdown<br />

to all things feminine.” Zaharias herself expressed<br />

scorn for traditionally “feminine” clothing and mannerisms,<br />

and according to a writer in Gay and Lesbian Biography,<br />

once told a reporter that “she did not wear girdles,<br />

bras, and the like because she was no ‘sissy.’”<br />

The common male response to her was summed up<br />

by Joe Williams, a contemporary reporter for the New<br />

York World-Telegram. According to Larry Schwartz in<br />

ESPN.com, Williams commented, “It would be much<br />

better if she and all her ilk stayed at home, got themselves<br />

prettied up and waited for the phone to ring.”<br />

Schwartz also noted that contemporary sportswriter<br />

Paul Gallico, who lost a golf match to Zaharias and<br />

Grantland Rice in 1932, called Zaharias a “muscle moll”<br />

in one Vanity Fair article, and commented in another<br />

Vanity Fair article that she was neither male nor female,<br />

and wrote dismissively that she was a lesbian. And according<br />

to Cayleff, it was not unusual for her to be accosted<br />

in the locker room by other female athletes who<br />

demanded to know whether she was a man or a woman.<br />

In addition to her androgynous personal style, Zaharias<br />

defied gender stereotypes of women’s need to be<br />

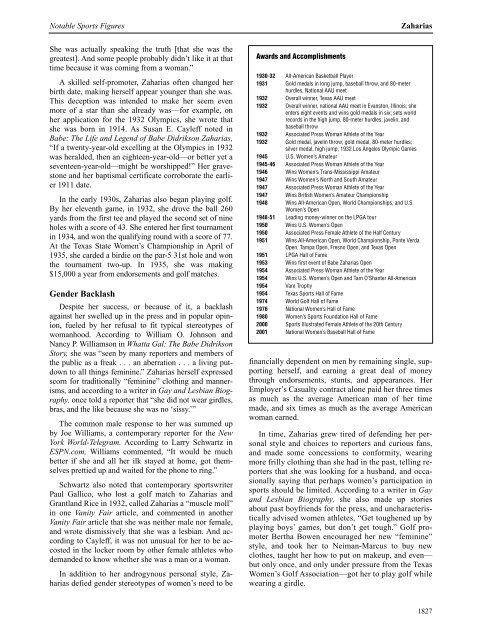

Awards and Accomplishments<br />

Zaharias<br />

1930-32 All-American Basketball Player<br />

1931 Gold medals in long jump, baseball throw, and 80-meter<br />

hurdles, National AAU meet<br />

1932 Overall winner, Texas AAU meet<br />

1932 Overall winner, national AAU meet in Evanston, Illinois; she<br />

enters eight events and wins gold medals in six; sets world<br />

records in the high jump, 80-meter hurdles, javelin, and<br />

baseball throw<br />

1932 Associated Press Woman Athlete of the Year<br />

1932 Gold medal, javelin throw; gold medal, 80-meter hurdles;<br />

silver medal, high jump, 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games<br />

1945 U.S. Women’s Amateur<br />

1945-46 Associated Press Woman Athlete of the Year<br />

1946 Wins Women’s Trans-Mississippi Amateur<br />

1947 Wins Women’s North and South Amateur<br />

1947 Associated Press Woman Athlete of the Year<br />

1947 Wins British Women’s Amateur Championship<br />

1948 Wins All-American Open, World Championships, and U.S.<br />

Women’s Open<br />

1948-51 Leading money-winner on the LPGA tour<br />

1950 Wins U.S. Women’s Open<br />

1950 Associated Press Female Athlete of the Half Century<br />

1951 Wins All-American Open, World Championship, Ponte Verda<br />

Open, Tampa Open, Fresno Open, and Texas Open<br />

1951 LPGA Hall of Fame<br />

1953 Wins first event of Babe Zaharias Open<br />

1954 Associated Press Woman Athlete of the Year<br />

1954 Wins U.S. Women’s Open and Tam O’Shanter All-American<br />

1954 Vare Trophy<br />

1954 Texas Sports Hall of Fame<br />

1974 World Golf Hall of Fame<br />

1976 National Women’s Hall of Fame<br />

1980 Women’s Sports Foundation Hall of Fame<br />

2000 Sports Illustrated Female Athlete of the 20th Century<br />

2001 National Women’s Baseball Hall of Fame<br />

financially dependent on men by remaining single, supporting<br />

herself, and earning a great deal of money<br />

through endorsements, stunts, and appearances. Her<br />

Employer’s Casualty contract alone paid her three times<br />

as much as the average American man of her time<br />

made, and six times as much as the average American<br />

woman earned.<br />

In time, Zaharias grew tired of defending her personal<br />

style and choices to reporters and curious fans,<br />

and made some concessions to conformity, wearing<br />

more frilly clothing than she had in the past, telling reporters<br />

that she was looking for a husband, and occasionally<br />

saying that perhaps women’s participation in<br />

sports should be limited. According to a writer in Gay<br />

and Lesbian Biography, she also made up stories<br />

about past boyfriends for the press, and uncharacteristically<br />

advised women athletes, “Get toughened up by<br />

playing boys’ games, but don’t get tough.” Golf promoter<br />

Bertha Bowen encouraged her new “feminine”<br />

style, and took her to Neiman-Marcus to buy new<br />

clothes, taught her how to put on makeup, and even—<br />

but only once, and only under pressure from the Texas<br />

Women’s Golf Association—got her to play golf while<br />

wearing a girdle.<br />

1827