- Page 1 and 2:

Acerca de este libro Esta es una co

- Page 3 and 4:

Adictionary of Greek and Roman anti

- Page 5 and 6:

p p

- Page 7:

DICTIONARY GREEK AND ROMAN ANTIQUIT

- Page 11:

LIST OF WRITERS. INITIALS. NAMES. A

- Page 14 and 15:

viii PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

- Page 16 and 17:

X TKEFACK TO THE FIRST EDITION. us

- Page 18 and 19:

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. " lit

- Page 20 and 21:

2 ABORTIO. ACCEPTILATIO. (Cic Verr.

- Page 22 and 23:

4 ACIIA1CUM FOEDUS. ACHAICUM FOEDUS

- Page 24 and 25:

6 ACINACES. ACROTERIUM. close union

- Page 26 and 27:

adventures, with the names of the p

- Page 28 and 29:

10 ACTIO. ACTIO. That body of law w

- Page 30 and 31:

12 ACTIO. ACTIO. might afterwards g

- Page 32 and 33:

11 ADLECTI ADOPTIO. taken from orig

- Page 34 and 35:

10 ADORATIO. ADULTERIUM. of very do

- Page 36 and 37:

18 AEDILES. AEDILES. of property. (

- Page 38 and 39:

Tiberius (Tacit. Ann. iv. 35.) The

- Page 40 and 41:

22 AENUM. AERARII. AEINAUTAE (aeiMt

- Page 42 and 43:

24 AERARIUM. AERARIUM. that it was

- Page 44 and 45:

26 AES EQUESTRE. AES UXORIUM. bronz

- Page 46 and 47:

28 AFFINES, AFF1NITAS. AGELA. of th

- Page 48 and 49:

30 AGER AGER they were called Subru

- Page 50 and 51:

■:.-2 AGORA. AGORA. The etymology

- Page 52 and 53:

24 AGORA. AGORA. also used as a tre

- Page 54 and 55:

36 AGORA. AORAPHIOU GRAPIIE. in the

- Page 56 and 57:

311 AGRARIAE LEGES. AGRARIAE LEGES.

- Page 58 and 59:

40 AGRARIAE LEGES. AGRARIAE LEGES.

- Page 60 and 61:

4 "J AG1URIAE LEGE& AGRARIAE LEGES.

- Page 62 and 63:

44 AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURA. was a

- Page 64 and 65:

46 AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURA. turn),

- Page 66 and 67:

48 AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURA. circum

- Page 68 and 69:

*© AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURA. oan

- Page 70 and 71:

52 AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURA. leu in

- Page 72 and 73:

54 AGRICULTURAL AGR1CULTURA. reeds

- Page 74 and 75:

S6 AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURA. for ma

- Page 76 and 77:

58 AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURA. having

- Page 78 and 79:

CO AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURA. horses

- Page 80 and 81:

62 AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURE tiroes

- Page 82 and 83:

the boves domestici. The common num

- Page 84 and 85:

66 AGRICULTURA. AORICULTURA. duce,

- Page 86 and 87:

C8 AGIUCULTURA. a sort of endive. I

- Page 88 and 89:

70 AGRICULTURA. AGRICULTURA. with u

- Page 90 and 91:

72 AGRIONIA AGROTERAS THUS1A. The A

- Page 92 and 93:

7i ALAUDA. A LEA. 4. Lastly, under

- Page 94 and 95:

7fi ALLUVIO. AMBITUS. African sand,

- Page 96 and 97:

78 AMBITUS. aMICTUS. in whole or in

- Page 98 and 99:

I AMPHICTYONES. 149; Dionys. iv. 25

- Page 100 and 101:

82 AMPHICTYONS. AMPHITHEATRUM. with

- Page 102 and 103:

84 AMPHITHEATRUM. AMPHITHEATRUM. si

- Page 104 and 105:

86 AMPH1THEATRUM. AMPHITHEATRUM. Th

- Page 106 and 107:

88 AMPHITHEATRUM. AMPHITHEATRUM. b.

- Page 108 and 109:

90 AMPHORA. AMPHORA. art. Aries.) B

- Page 110 and 111:

92 ANAKEIA. ANAKRISIS. describes it

- Page 112 and 113:

94 ANAXAGOREIA. ANGARIA. was differ

- Page 114 and 115:

ANNULUS. Antonius Musa, a physician

- Page 116 and 117:

98 ANTEFIXA. ANTIDOSIS. moulds, and

- Page 118 and 119:

■ 100 ANTLIA. . ANTLIA. From what

- Page 120 and 121:

102 APEX, APHRODISIA. tim was remov

- Page 122 and 123:

101 APOPHORA. APOSTOLEIS. place. Ac

- Page 124 and 125:

10« APPELLATIO. APPELLATIO. be obt

- Page 126 and 127:

103 AQUAEDUCTUS. AQUAEDUCTUS. to ci

- Page 128 and 129:

110 AQUAEDUCTUS. AQUAEDUCTUS. Its l

- Page 130 and 131:

i I 112 AQUAEDUCTUS. AQUAEDUCTUS. a

- Page 132 and 133:

114 AQUAEDUCTUS. AQUAEDUCTUS. Aqua

- Page 134 and 135:

116 AHA. ARA. land ; or by the owne

- Page 136 and 137:

118 ARATRUM. ARATRUM. (Excursion in

- Page 138 and 139:

120 AUCHITECTURA. ARCHITECTURA. gov

- Page 140 and 141:

122 ARCIION. ARCHON. after passing

- Page 142 and 143:

124 ARCIION. AKCUS. (">Spto>s yp&pa

- Page 144 and 145:

126 ARCUS. AUEIOPAGUS. specimens of

- Page 146 and 147:

128 AREIOPAGUS. AREIOPAGUS. demos.

- Page 148 and 149:

130 AROENTARII. ARGENTARII. to Home

- Page 150 and 151:

132- ARGENTUM. ARGENTUM. Sat. i. 6.

- Page 152 and 153:

134 ARISTOCRATIA. ARISTOCRATIA. ari

- Page 154 and 155:

136 AKMILLA. ARMILLA. properly bell

- Page 156 and 157:

138 ARVALES FRATRES. ARVALES FRATRE

- Page 158 and 159:

WO AS. AS. were accompanied by a re

- Page 160 and 161:

142 ASEBEIAS ORAPHE. ASILLA. a he-g

- Page 162 and 163:

,44 ASTROLOGIA. ASTROLOGIA. in the

- Page 164 and 165:

I4C ASTRONOMIA. which, as we are as

- Page 166 and 167:

ASTRONOMIA. tan in the Little Bear

- Page 168 and 169:

ISO ASTRONOMIA. ASTRONOMIA. Hclle f

- Page 170 and 171:

152 ASTROXOMIA. ASTRONOMIA. Great F

- Page 172 and 173:

154 ASTRONOMIA. ASTRONOMIA. Before

- Page 174 and 175:

156 ASTRONOMIA. ASTRONOMIA. other h

- Page 176 and 177:

ASTRONOMIA. he inculcates may be th

- Page 178 and 179:

160 ASTRONOMIA. ASTRONOMIA. month o

- Page 180 and 181:

1 02 ASTRONOMIA. ASTRONOMIA. " Orio

- Page 182 and 183:

164 ASTltONOMIA. ASTRONOMIA. Aeschy

- Page 184 and 185:

ATELEIA. § 12). ThiB constitutio o

- Page 186 and 187:

1GB ATIMIA. have been frequently co

- Page 188 and 189:

170 ATLANTE& ATRAMENTUM. Hating con

- Page 190 and 191:

172 AUCTIO. AUCTOR. above and below

- Page 192 and 193:

174 AUGUR. AUGUR. probation and con

- Page 194 and 195:

176 AUGUR. AUGUR. came the practice

- Page 196 and 197:

173 AUGUR. AUGUR nuntiafio (perhaps

- Page 198 and 199:

180 AUGUSTALES. AURUM. Gruter (316.

- Page 200 and 201:

182 AURUM. AUSP1CIUM. came into cir

- Page 202 and 203:

liU BALNEAE. BALNEA E. balnearum (l

- Page 204 and 205:

186 BALNEAE. BALNEAE. describes the

- Page 206 and 207:

188 BALNEAE. BALNEAE. to as a daily

- Page 208 and 209:

.90 BALNEAE. BALNEAE. construction,

- Page 210 and 211:

1.0-2 BALNEAE. BALNEAE. kemixphaeri

- Page 212 and 213:

194 BALNEAE. BALNEAE. ample remains

- Page 214 and 215:

136 BALTEUS. BARBA. the lower oncB

- Page 216 and 217:

198 BASILICA, BASILICA. something b

- Page 218 and 219:

200 BASILICA. BAXA. empire apply th

- Page 220 and 221:

202 BIBLIOTHECA. BIBLIOTHKCA. son w

- Page 222 and 223:

sider that the damage done by Philo

- Page 224 and 225:

206 BONA, BONA CADUCA. in the same

- Page 226 and 227:

208 BONORUM EMTIO, BONORUM POSSESSI

- Page 228 and 229:

210 BOULE. BOULE. representative, a

- Page 230 and 231:

212 BOULE. BOULE. and responsible (

- Page 232 and 233:

214 BRAURONIA. BREVIARIUM. at Spart

- Page 234 and 235:

210 BYSSUS. CACABUS. Verr. i. 58) ;

- Page 236 and 237:

218 CADUS. CAELATURA. were brought,

- Page 238 and 239:

220 CALATHUS. CALCEUS. 12. s.55, xx

- Page 240 and 241:

222 CALENDAR! UM. CALENDARIUM. The

- Page 242 and 243:

224 CALENDARIUM. CALENDARIUM. It sh

- Page 244 and 245:

226 CALENDARIUM. CALENDARIUM. The s

- Page 246 and 247:

221 CALENDARIUM. CALENDAR! UM. way

- Page 248 and 249:

230 CALENDARIUM. CALENDARIUM. We gi

- Page 250 and 251:

232 CALENDARIUM. CALENDARIUM. refer

- Page 252 and 253:

nian LVmeter. The women taking part

- Page 254 and 255:

235 CANDELABRUM. CANDELABRUM. the c

- Page 256 and 257:

238 CAPISTRUM. CAPSA. form. (Athen.

- Page 258 and 259:

210 CARCER. CARCER. A judicium capi

- Page 260 and 261:

242 CARNIFEX. CARPENTUM. Carncios,

- Page 262 and 263:

2-U CASTRA. CASTRA. CASSIS. [Galea

- Page 264 and 265:

246 CASTRA. CASTRA. march by a regu

- Page 266 and 267:

248 CASTRA. CASTUA. and left of the

- Page 268 and 269:

250 CASTRA. CASTRA rally speaks of

- Page 270 and 271:

212 CASTRA. CASTRA. (Fig. 3.) PORTA

- Page 272 and 273:

254 CASTRA, CASTRA. perhaps the Pra

- Page 274 and 275:

25t> CATAPIIRACTI. CATARACTA. (Ta£

- Page 276 and 277:

The word KairnKuoy signified, as ha

- Page 278 and 279:

CELLA. if any person recovered it f

- Page 280 and 281:

362 CENSOR. CENSOR. the emperors in

- Page 282 and 283:

264 CENSOR. CENSOR. ing the animadv

- Page 284 and 285:

2S6 CENSUS. CENSUS. of the censorsh

- Page 286 and 287:

268 CEREALIA. CERTI. in early timet

- Page 288 and 289:

270 CIIALCIDICUM. CIIARISTIA. decor

- Page 290 and 291:

272 CHIRURGIA. CHIRURGIA. given to

- Page 292 and 293:

274 CHIltURGIA. CHIRURGIA. entirely

- Page 294 and 295:

CHOREGUS. (chlamyde coecinca, Lampr

- Page 296 and 297:

278 CHORUS. CHORUS. dence, are best

- Page 298 and 299:

280 CHORUS. CHRONOLOG1A. TpayipSia

- Page 300 and 301:

282 CHTHONIA. UPPU& themselves. M.

- Page 302 and 303:

2S14 CIRCUS. CIRCUS. J terniption t

- Page 304 and 305:

286 CIRCUS. CIRCUS. Murciam, from t

- Page 306 and 307:

388 CISTA CIVITAS. times the contes

- Page 308 and 309:

290 CIVITAS. CIVITAS. maternal gran

- Page 310 and 311:

202 CIVITAS. CIVITAS. form, of beco

- Page 312 and 313:

294 . CLAVUS LATUS. CLIENS. and Abe

- Page 314 and 315:

296 CM ENS. CLIMA. It is stated by

- Page 316 and 317:

290 CLIPEUS. CLIPEUS. Ttpiipipna or

- Page 318 and 319:

300 KLOPES DIKE. COCHLEA. year 1742

- Page 320 and 321:

302 CODEX. CODEX. Justinian himself

- Page 322 and 323:

304 COENA. COENA. sit down together

- Page 324 and 325:

300 COENA. COENA. and the introduct

- Page 326 and 327:

308 COENA. COENA. ivory or tortoiae

- Page 328 and 329:

I 310 COGNATL COLLEGIUM. Tritavus,

- Page 330 and 331:

312 COLONATUS. COLONATUS. should go

- Page 332 and 333:

314 COLONIA. COLON IA. a colony of

- Page 334 and 335:

316 . COLON 1 A. COLONIA. for suppo

- Page 336 and 337:

318 COLON I A. COLONIA. strangers t

- Page 338 and 339:

320 COLORES. COLORES. the passing o

- Page 340 and 341:

322 COLOSSUS. COLUM. vapair6ptov% s

- Page 342 and 343:

324 COLUMNA. COLUMNA. each of the p

- Page 344 and 345:

326 COLUMN.*. COLUMNA, cornice betw

- Page 346 and 347:

COLUMNARIUM. capital. The inscripti

- Page 348 and 349:

330 COMES. COMITTA. pillus, caesart

- Page 350 and 351:

333 COMITIA. COMITIA. certain ; and

- Page 352 and 353:

331 COMITIA. COMITIA. According to

- Page 354 and 355:

336 COMITIA. COMITIA. ho might gran

- Page 356 and 357:

338 COMITIA. COMITIA. legislative c

- Page 358 and 359:

340 COMITIA. COMMISSORIA LEX. able

- Page 360 and 361:

and violets, and threw skins round

- Page 362 and 363:

344 COMOEDIA. COMOEDIA. than with t

- Page 364 and 365:

own absurdity. It is perfectly clea

- Page 366 and 367:

348 CONCILIUM. CONCIO. yicc of slav

- Page 368 and 369:

350 CONFUSIO. CONGIARIUM. CONFESSO'

- Page 370 and 371:

352 CONSUL, CONSUL. the founder of

- Page 372 and 373:

354 CONSUL. CONSUL. with the census

- Page 374 and 375:

356 CONSUL. CONSUL. nominate a dict

- Page 376 and 377:

358 CORBIS. CORNU. (Caes. Bell. Coi

- Page 378 and 379:

360 CORONA. CORONA. him that defere

- Page 380 and 381:

3G2 CORONA. CORONA. parties, were s

- Page 382 and 383:

364 CORYBANTICA. COSMKTAE. of which

- Page 384 and 385:

3GG COTHURNUS. The slave* were divi

- Page 386 and 387:

US CRATER. CRIMEN. place in the nty

- Page 388 and 389:

ero CROTALUM. . CRUX. or KpoKtarbs

- Page 390 and 391:

372 CUBITUS. CUDO. their masters to

- Page 392 and 393:

374 CUPA. CURATOR. ii. p. G40. No.

- Page 394 and 395:

perspicuity of the language. ( Von

- Page 396 and 397:

578 CURRUS. CURRUS. resident alien,

- Page 398 and 399:

sno CURRUS. CYATIIUS. plete suits o

- Page 400 and 401:

882 DAEDALA. DAMARETION. •f a cym

- Page 402 and 403:

804 DAPHNEPIIORIA. DARICUS. ■moth

- Page 404 and 405:

"3CG DECEMVIRI. DECEMVIRI. Accordin

- Page 406 and 407:

388 DEJECTI EFFUSIVE ACTIO, delator

- Page 408 and 409:

390 DEM10PRATA. DEMOCRATIA. been fi

- Page 410 and 411:

592 DEMUS. DEMUS. off from the wast

- Page 412 and 413:

391 DEPOSITUM. DESULTOR. is equal i

- Page 414 and 415:

396 DIAETETICA. DIAETETAE. the mean

- Page 416 and 417:

son DIAETETAE. great importance, in

- Page 418 and 419:

400 DIAPSEPIIISIS. DIASIA. forth an

- Page 420 and 421:

402 DICASTES. DIKE. the Ilissus, bu

- Page 422 and 423:

404 DIKE. DICTATOR. render him liab

- Page 424 and 425:

406 DICTATOR. DICTATOR. In the same

- Page 426 and 427:

408 DIES. DIES. find at a later tim

- Page 428 and 429:

•10 DIMACHERI. DIONY81A. causa cu

- Page 430 and 431:

412 DIONYSIA. DIONYSIA. days, and t

- Page 432 and 433:

414 DIONYSIA. DIRIBITORES. their pa

- Page 434 and 435:

410 DTVINATIO. DIVINATIO. kinds of

- Page 436 and 437:

418 DIVORTIUM. DIVORTIUM. duct the

- Page 438 and 439:

the other hand, figs. 5, 6, 7, exac

- Page 440 and 441:

422 DOMINIUM. DOMINIUM. (Ulp. Frag,

- Page 442 and 443:

+21 DOM US. DOMUS. by Lysias (De Ca

- Page 444 and 445:

420 DOM US. DOMUS. Portions of the

- Page 446 and 447:

428 DOMUS. DOM US. Carm. iii. 1. 46

- Page 448 and 449:

DOMUS. the family, or intended for

- Page 450 and 451:

432 DOMUS. DONARIA. (3.) The ceilin

- Page 452 and 453:

434 DONATIO. DONATIO MORTIS CAUSA.

- Page 454 and 455:

436 DOS. DOS. DORMITO RIA. [Domus.]

- Page 456 and 457:

430 DRACHMA, DRACHMA. the husband m

- Page 458 and 459:

4 II) ECCLESIA. ECCLESIA. being to

- Page 460 and 461:

442 ECCLESIA. ECCLESIA. traitorousl

- Page 462 and 463:

441 EDICTUM. EDICTUM. of this assem

- Page 464 and 465:

446 EDICTUM THEODORICI. EISAGOGEIS.

- Page 466 and 467:

448 EISANGELIA. EISPHORA. (Don. e,

- Page 468 and 469:

450 ELECTRUM. ELECTRUM. (Demosth.e.

- Page 470 and 471:

452 ELEPIIAS. ELEUSINIA. tot up at

- Page 472 and 473:

454 ELEUSINIA. ELEUTHERIA. mystae n

- Page 474 and 475:

456 EMBATEIA. EMBLEMA. emancipate a

- Page 476 and 477:

EMPHYTEUSIS. words of Pliny (I. c.)

- Page 478 and 479:

460 ENECHYRA. ENGYE. this kind. Her

- Page 480 and 481:

462 EPEUNACTAE. F.PIIEBUS. EO'RA. [

- Page 482 and 483:

the use of saddles was unknown unti

- Page 484 and 485:

466 EPHORI. EPIBATAE. and who is sa

- Page 486 and 487:

4C8 EPIMELETAE. EPISTATES. the offe

- Page 488 and 489:

470 EPOBELIA. EPULONES. mortgages,

- Page 490 and 491:

472 EQU1TES. EQUITES. latter to 200

- Page 492 and 493:

474 EQUITES. EQUITES. be qualified

- Page 494 and 495:

476 ESSEDA. EVICTIO. gilds, or frat

- Page 496 and 497:

478 EUTHYNE. EUTHYNE. of the highes

- Page 498 and 499:

4!10 EX EG ETA E. EXERCITORIA ACTIO

- Page 500 and 501:

482 EXERCITUS. EXERCITUS. qucntly e

- Page 502 and 503:

484 EXERC1TUS. EXERCITUS. which Her

- Page 504 and 505:

486 EXERCITUS. EXERCITUS. Only the

- Page 506 and 507:

488 EXERCITUS. EXERCITUS. The geniu

- Page 508 and 509:

4f)0 EXERCITUS. EXERCITUS. without

- Page 510 and 511:

4M EXERCITUS. practice first introd

- Page 512 and 513:

494 EXERCITUS. EXERCITUS. 4. From t

- Page 514 and 515:

4% EXERCITUS. EXERCITUS. sections,

- Page 516 and 517:

4!>8 EXERCITUS. EXERCITUS. culiar d

- Page 518 and 519:

500 EXERCITUS. EXERCITUS. the kings

- Page 520 and 521:

502 EXERCITUS. EXKRCITUS. In corrob

- Page 522 and 523:

504 EXERCITUS. EXERCITUS. a law of

- Page 524 and 525:

EXERCITUS. valuable to the state. I

- Page 526 and 527:

veterans of Julius Caesar to aid hi

- Page 528 and 529:

I Urbanae Cohortcs. — We may take

- Page 530 and 531:

512 EXODIA. EXOMOSIA. declare wheth

- Page 532 and 533:

614 EXSILIUM. EXSIL1UM. satisfied,

- Page 534 and 535:

«16 EXSILIUM. EXSILIUM. cally corr

- Page 536 and 537:

518 FALX. FALX. and Taurus, as it s

- Page 538 and 539:

520 FARTOR. FASCES. traced to the P

- Page 540 and 541:

522 FASTI. FASTI. denominated fasti

- Page 542 and 543:

.',24 FAX. FENUS. from a flat one,

- Page 544 and 545:

526 FEN US. FEN US. The rate of int

- Page 546 and 547:

528 FERIAE. FERIAE. nion that it wa

- Page 548 and 549:

530 FESCENNINA. FETIALES. common sa

- Page 550 and 551:

632 FIBULA. FICTILE. Ovid, Met Till

- Page 552 and 553:

531 FICTILE, FICTIO x. 35 ; Schol.

- Page 554 and 555:

FIDEICOMMISSUM. FIDUCIA. be the obj

- Page 556 and 557:

£38 FISTUCA. FISTULA. cus were oft

- Page 558 and 559:

MO FLAMEN. FLAMEN. was knotted with

- Page 560 and 561:

FOCUS. i. 3; Senec Epist. 96.) From

- Page 562 and 563:

544 FONS. FONS. out of which the wa

- Page 564 and 565:

.146 FORNAX. FORUM Lot. vi. 13, wit

- Page 566 and 567:

£48 FRENUM. frtjmi:ntariae leges.

- Page 568 and 569:

650 FRUMENTARIAE LEGES. FRUMENTARIA

- Page 570 and 571:

552 FULLO. FULLO. latter of which w

- Page 572 and 573:

554 FUNDUS. FUNUS. deJieMil L 1 6 ;

- Page 574 and 575:

536 FUNUS. FUNUS. ceding woodcut co

- Page 576 and 577:

553 FUNUS. FUNUS. 601?, &c, Ototph

- Page 578 and 579:

I 5G0 FUN US. called Itustuariiy we

- Page 580 and 581:

■ SG2 FUNUS. FURCA. honour of the

- Page 582 and 583:

5G1 FURTUM. a thing-, therefore, ha

- Page 584 and 585:

566 GALEA. GALLI. Herefordshire. (S

- Page 586 and 587:

GENS. with the definition of the Po

- Page 588 and 589:

570 GENS. GEOMORI. prescntntivos of

- Page 590 and 591:

572 GEROUSIA. GEROUSIA. gativcs j t

- Page 592 and 593:

.',74 GLADIATORES. GLADIATORES. not

- Page 594 and 595:

576 GLADIATORES. GLADIATORES. Tned.

- Page 596 and 597:

57a GRAPIIE. Jjpg. p. 419 ; de Coro

- Page 598 and 599:

580 GYMNASIUM. GYMNASIUM. from some

- Page 600 and 601:

S82 GYMNASIUM. GYMNASIUM. strewing

- Page 602 and 603:

.5(14 GYMNOPAEDIA. GYNAECONOMI. chi

- Page 604 and 605:

m." The commentators have laboured

- Page 606 and 607:

583 HASTA. HASTA. wrre particularly

- Page 608 and 609:

690 HELEPOLIS. IIELLENOTAMIAE. and

- Page 610 and 611:

vavrai, and FeoSafiwSfis. Of these

- Page 612 and 613:

m HERES. HERES. (Sec Schol. ad Pind

- Page 614 and 615:

696 HERES. HERES. It was only when

- Page 616 and 617:

598 HERES. II EKES. the state of At

- Page 618 and 619:

coo HERES. HERES. that time the pro

- Page 620 and 621:

602 HERMAE. HERMAE. which the hered

- Page 622 and 623:

cot IIERMAEA. HF.TAERAE. The Hcrmae

- Page 624 and 625:

608 IIETAIRESEOS GRAPIIE. HIERODULI

- Page 626 and 627:

608 HIPPODAMEIA. HIPPODROMUS. HILA'

- Page 628 and 629:

610 HIPPODIIOMUS. HIPPODIIOMUS. the

- Page 630 and 631:

6)2 HISTRIO. 1IISTRIO. the actors w

- Page 632 and 633:

614 HORA. IIORI. HOPLI'TAE (owAiTai

- Page 634 and 635:

616 HOROLOGIUM. HOROLOGIUM. made to

- Page 636 and 637:

618 HORTUS. IIORTUS. HORUEA'RII. [H

- Page 638 and 639:

C20 IIOSPITIUM. tomary among oursel

- Page 640 and 641:

622 HYBREOS GRAPH E. HYDRAULA. cond

- Page 642 and 643:

624 IIYSPLENX. JANUA. trial, the pr

- Page 644 and 645:

62G JANUA. JANUA. Even each valve w

- Page 646 and 647:

C23 ILLUSTRES. of this harsh admoni

- Page 648 and 649:

auctoritas of his tutor, but he cou

- Page 650 and 651:

632 INAURIS. INCENDIUM. inauguratio

- Page 652 and 653:

634 INCUNABULA. INFAMIA. cording to

- Page 654 and 655:

636 INFANS, INFANTIA. INFANS, INFAN

- Page 656 and 657:

638 INSIGNE. INSIGNE. was not bound

- Page 658 and 659:

C40 1NSTITUTIONES. INTERCESSIO. the

- Page 660 and 661:

G42 INTERDICTUM. INTERDICTUM. his c

- Page 662 and 663:

644 INTERDICTUM. INTERREX. its orig

- Page 664 and 665:

646 ISTHMIA. JUDEX, JUDICIUM. to Th

- Page 666 and 667:

tf4« JUDEX, JUDICIUM. JUDEX, JUDIC

- Page 668 and 669:

650 JUDEX, JUDICIUM. JUDEX, JUDICIU

- Page 670 and 671:

6.V2 JUGUM. JUGUM. was used for a s

- Page 672 and 673:

6.51 JURISCONSULTI. JURISCONSULTI.

- Page 674 and 675:

for the explanation of Jus Naturals

- Page 676 and 677:

658 JUS. JUS. last title of the fou

- Page 678 and 679:

660 JUSJUItANDUM. JUSJUIUNDUM. Paul

- Page 680 and 681:

66*2 JUSJURANDUM. JUSJURANDUM. and

- Page 682 and 683:

664 LABYRINTHUS. LABYRINTHUS. twent

- Page 684 and 685:

666 LAMPADEPHORIA. LAMPADEPHORIA. o

- Page 686 and 687:

6G8 LATER, LATER. and in which thei

- Page 688 and 689:

670 LATIKITA& LATRUNCULI. terms he

- Page 690 and 691:

I C72 LECTICA. pears to have been c

- Page 692 and 693:

674 LECTUS. • LKCTUS. to support

- Page 694 and 695:

676 LEGATUM. LEGATUM. tarian owners

- Page 696 and 697:

578 LEGATU& LEGATUS. came from an a

- Page 698 and 699:

€80 LEMNISCUS. LENO. they were pe

- Page 700 and 701:

6T,2 LEX. LEX. but this definition,

- Page 702 and 703:

6

- Page 704 and 705:

equired the formalities already men

- Page 706 and 707:

688 LEX DUODECIM TABULARUM. LEX DUO

- Page 708 and 709:

,90 LEX OABINIA. LEGES JULIAE. tema

- Page 710 and 711:

092 LEGES JUL1AE. LEGES JULIAE. pae

- Page 712 and 713:

694 LEX LICINIA. LEX MANLIA. effect

- Page 714 and 715:

VJG LEX PUBLILIA. LEGES PUBLILIAE.

- Page 716 and 717:

698 LEX SATURA. LEGES SEMPRONIAE. a

- Page 718 and 719:

700 LEX TIIOIUA. LEGES VALERIAE. fi

- Page 720 and 721:

702 LEX VOCONIA. LIBELLU& the Lei n

- Page 722 and 723:

704 LIBER. LIBERALITAS. It is said

- Page 724 and 725:

706 LIBRA, LIBRARII. and the descen

- Page 726 and 727:

70fl LITIS CONTESTATIO. LITIS CONTE

- Page 728 and 729:

710 LODIX. LOPE. LIXAE. [Calonks.]

- Page 730 and 731:

712 LORICA. LORICA. ing plate which

- Page 732 and 733:

714 LUCTA. LUDI. aiso presided over

- Page 734 and 735:

716 LUDI PLEBEII. LUDI SAECULABES.

- Page 736 and 737:

7111 LUPKRCALIA. LUPERCI. LUDUS LAT

- Page 738 and 739:

720 LYRA. LYRA. 43) which happened

- Page 740 and 741:

722 MACH1NAE. MACHINAE. steelyard (

- Page 742 and 743:

724 MAGISTRATES. MAJESTAS. expired.

- Page 744 and 745:

72fi MALLEUS. MANCIPII CAUSA. ginal

- Page 746 and 747:

728 MANDATI ACTIO. MANDATUM. 6) def

- Page 748 and 749:

730 MANUMISSIO. MANUMISSIO. 79.) Th

- Page 750 and 751:

7:12 MARIS. MARTYRIA. tium z milia

- Page 752 and 753:

734 MARTYRIA. MARTYRIA. c Theocr. 1

- Page 754 and 755:

736 MATRIMONIUM. MATRIMONIUM. The c

- Page 756 and 757:

738 MATRIMONIUM. MATRIMONIUM. bride

- Page 758 and 759:

740 MATRIMONIUM. MATRIMONIUM. ati A

- Page 760 and 761:

7(2 MATRIMONIUM. MATRIMONIUM. influ

- Page 762 and 763:

MAUSOLEUM. old Fescennina [Fescenni

- Page 764 and 765:

745 11EDICINA. MEDICINA. sicknesses

- Page 766 and 767:

718 MEDICUS. MEDIX TUTICUS. by him

- Page 768 and 769:

750 MENSARII. MENSURA. vention of t

- Page 770 and 771:

752 MENSURA. MEXSURA. whole hand fr

- Page 772 and 773:

754 MENSURA. MENSURA. systems, whic

- Page 774 and 775:

756 MENSURA. MENSURA. The following

- Page 776 and 777:

758 MERCENARII. MERCENARII. Greek a

- Page 778 and 779:

760 METALLUM. METALLUM. of the earl

- Page 780 and 781:

i METRETES. were left open ; next t

- Page 782 and 783:

764 MISTIIOU DIRE. MODULUS, from J.

- Page 784 and 785:

7CG MONETA. MONETA. situated on som

- Page 786 and 787:

763 MORA. MORTA1UUM. woodcut immedi

- Page 788 and 789:

770 MURU& MURUS. Etniria, mid in Ce

- Page 790 and 791:

772 MURUS. MUSICA. wall, the interi

- Page 792 and 793:

774 MUSICA. MUSICA. •troy the con

- Page 794 and 795:

776 MUSICA. MUSICA. In adapting the

- Page 796 and 797:

778 MUSICA. MUSICA. must have forme

- Page 798 and 799:

780 MUSTAX. MYSIA. Roman musical sy

- Page 800 and 801:

782 NAVARCHUS. NAUCRARIA. monies co

- Page 802 and 803:

784 NAVIS. NAVIS. It is a general o

- Page 804 and 805:

786 NAVIS. NAVIS. but the reading i

- Page 806 and 807:

NAVIS. very improbable, as tbe comm

- Page 808 and 809:

7t>0 NAVIS. NAVIS. together. They r

- Page 810 and 811:

792 NAVIS. NAUMACIIIA. A . Prora, i

- Page 812 and 813:

794 NEGOTIORUM GESTORUM ACTIO. NEME

- Page 814 and 815:

7UG NEXUM. rity: accordingly in one

- Page 816 and 817:

NEXUM. NOBILES. and consequently co

- Page 818 and 819:

nno NOMEN. Patrician was of seconda

- Page 820 and 821:

802 NOMEN. NOMEN. were very numerou

- Page 822 and 823:

G04 NOMOS. NOMOS. to the advice of

- Page 824 and 825:

806* NOTA. NOTA. which two votes of

- Page 826 and 827:

808 NOXALIS ACTIO. NUMMUS. had a No

- Page 828 and 829:

810 NUMMUS. NUMMUS. ancient copper

- Page 830 and 831:

812 NUMMUS. NUMMUS. netan talent co

- Page 832 and 833:

814 NUMMUS. NUMMUS. {Ultra, \lrpa)

- Page 834 and 835:

IllG NUNDINAE. deo caret. But at th

- Page 836 and 837:

mil OnLIGATJONES. effected by words

- Page 838 and 839:

,-20 OBLIGATION ES. OBLIGATION ES.

- Page 840 and 841:

822 OCREA. ODEUM. citizens, who wer

- Page 842 and 843:

OLEA. emblem of industry and peace.

- Page 844 and 845:

626 OLEA. OLIGARCH I A. oil obtaine

- Page 846 and 847:

OLYMPIA. preserved by A. Lawson Esq

- Page 848 and 849:

first 1 3 Olympiads. 2. The ShxuAot

- Page 850 and 851:

832 OLYMPIA. OLYMPIA. celebrated fr

- Page 852 and 853:

831 OLVMPIAS. OLYMPIAS. ac. 01 B,a

- Page 854 and 855:

836 OPSONIUM. ORACULUM. articles we

- Page 856 and 857:

838 ORACULUM. ORACULUM. (Pint, de P

- Page 858 and 859:

840 ORACULUM. ORACULUM. 1 6. Oracle

- Page 860 and 861:

842 ORACULUM. ORACULUM. after this

- Page 862 and 863:

acquired by discipline ; whereas a

- Page 864 and 865:

C46 OVATIO. PAEAN. viz. wine, honey

- Page 866 and 867:

848 PAENULA. PALA. PAEDO'NOMUS (rai

- Page 868 and 869:

o.-jo PALILIA. 5. r. ParilAus ; Cic

- Page 870 and 871:

852 PALLIUM. PALLIUM. been to the f

- Page 872 and 873:

854 PALUDAMENTUM. PAMBOEOTIA. down

- Page 874 and 875:

856 PANATIIENAEA. PANATHENAEA. viii

- Page 876 and 877:

stitution addressed to Tribonian em

- Page 878 and 879:

PANDECTAE. bequests. There is a met

- Page 880 and 881:

862 PANTOMIMUS. PANTOMIMUS. religio

- Page 882 and 883:

the last case the vapayptup^ would

- Page 884 and 885:

VA .!■>'. -n«tn * nad *l*naM umt

- Page 886 and 887:

96vtqs tov xpoVov, iv $ inrtvBvyos

- Page 888 and 889:

870 PARMA. PAROPSIS. splendid edifi

- Page 890 and 891:

872 PATERA. PATINA. British Museum,

- Page 892 and 893:

871 PATRIA POTESTAS. PATR1A POTESTA

- Page 894 and 895:

87G PATRICII. PATRICII. jiatres leg

- Page 896 and 897:

PATRONUS (b. c. 236—221), who des

- Page 898 and 899:

aiio PATRON US equal share (rirtfia

- Page 900 and 901:

y the laborious poor, as is still t

- Page 902 and 903:

884 PENTECOSTE. PEPLUM. to him who

- Page 904 and 905:

n«s PERA. PERGULA. . to him for th

- Page 906 and 907:

688 PERIOECI. PERIOECX. truth, or a

- Page 908 and 909:

no PERSONA. covered, like the masks

- Page 910 and 911:

092 PERSONA. PERSONA. •Kwywv, or

- Page 912 and 913:

P.!) I PHALERA. 156.) AVc also find

- Page 914 and 915:

flf'O PHASIS. PJION05. Steph.), we

- Page 916 and 917:

B38 PHONOS. PHTHORA TON ELEUTHERON.

- Page 918 and 919:

ft 00 PICTURA. U'r~Lexicon, Miinchc

- Page 920 and 921:

.002 PICTURA. PICTURA. had a pictur

- Page 922 and 923:

1)04 PICTUKA. PICTURE v. p. 204, b.

- Page 924 and 925:

906 PICTURA. PICTURA. to have been

- Page 926 and 927:

PICTURA. others, in which the illus

- Page 928 and 929:

he termed himself the prince of pai

- Page 930 and 931:

912 PICTURA. PICTURA. mere means, t

- Page 932 and 933:

91 i TICTURA. PICTURA. the only one

- Page 934 and 935:

916 PIGNUS. PIGNUS. thing by bare a

- Page 936 and 937:

618 PI LA. PILA. the timber should

- Page 938 and 939:

920 PILEUS. PILEUS. the British Mus

- Page 940 and 941:

922 PLANETAE. PLANETAE. PLANETAE, s

- Page 942 and 943:

924 PLEBES. PLEBES. story mentioned

- Page 944 and 945:

926 TLEBES. PLEHES. exaggerated to

- Page 946 and 947:

928 PLUMARII. POCULUM. a Concilium,

- Page 948 and 949:

930 POMOERIUM. POMOERIUM. p. 371, b

- Page 950 and 951:

9312 PONDERA. PONDERA. the Greeks,

- Page 952 and 953:

5)31 PONDERA. PONDERA. commercial d

- Page 954 and 955:

936 PONDERA. PONS. should be compel

- Page 956 and 957:

938 PONS. PONS. V. Pons Janiculinri

- Page 958 and 959:

91 0 rONTIFEX. PONTIFEX. possible t

- Page 960 and 961:

S4-2 PONTIFEX. PORISTAE. called tut

- Page 962 and 963:

914 PORTICUS. PORTORIUM. (Wyttenbac

- Page 964 and 965:

fU6 POSSESSIO. POSSESSIO. except th

- Page 966 and 967:

948 POSSESSIO. POSSESSIO. which are

- Page 968 and 969:

550 POSTLIMINIUM. POSTLIMINIUM. tho

- Page 970 and 971:

952 PRAEFECTUS ANNONAE. was the pra

- Page 972 and 973:

9i4 PIIAEJUDICIUM. tit 28. s. 1 ; O

- Page 974 and 975:

9oG PRAETOR. tion of the tiered ita

- Page 976 and 977:

958 PRIMICERIUS, PROBOLE. bers and

- Page 978 and 979:

960 PROBOULI. PROCONSUL. nnunce the

- Page 980 and 981:

PRODOSIA. trials for constructive t

- Page 982 and 983:

964 PHOTHESMIA. PROVINCIA. during t

- Page 984 and 985:

066 PROVINCIA. PROVINCIA. of Phrygi

- Page 986 and 987:

968 PROVINCIA. PROVINCIA. saris in

- Page 988 and 989:

970 PRYTANEION. PSEPH1SMA. the diff

- Page 990 and 991:

972 PSEUD0CLETE1AS GRAPH E. PUBLICA

- Page 992 and 993:

974 PUBLICIANA IN REM ACTIO. PUGILA

- Page 994 and 995:

B7C PYANEPSIA. Servius, in Virg. Gr

- Page 996 and 997:

078 PYTHIA. QUADRAGESIMA. It is qui

- Page 998 and 999:

580 QUAESTOR. QUAESTOR, the - _ Rom

- Page 1000 and 1001:

902 QUANTI MINORIS. QUINQUATRUS. th

- Page 1002 and 1003:

PfU quorum bonorum. HFXEPTA. If he

- Page 1004 and 1005:

986 REPETUNDAE. REPETUNDAE. scale-b

- Page 1006 and 1007:

9C3 RESTITUTIO IN INTEGRUM. RETls.

- Page 1008 and 1009:

990 REX. REX. Its Latin names are f

- Page 1010 and 1011:

992 REX. REX. which the people coul

- Page 1012 and 1013:

994 REX SACRIFICULUS. RHETRAE. For

- Page 1014 and 1015:

990 RUTRUM. SACERDOS. enabled to wa

- Page 1016 and 1017:

j SACRA. SACRIFICIUM. pion with the

- Page 1018 and 1019:

1000 SACRIFICIUM. SAECULUM. sacrifi

- Page 1020 and 1021:

1002 SAGUM. SAL1ENTES. III. The fea

- Page 1022 and 1023:

1001 SALINUM. SALTATIO. flat as to

- Page 1024 and 1025:

1006 SATVTATIO. SALUTATORES. these

- Page 1026 and 1027:

1008 SATURA. # SATURA. SA'RCULUM (a

- Page 1028 and 1029: 1010 SCALPTURA. SCALPTURA. •true

- Page 1030 and 1031: 1013 SCRIPTURA. SCUTUM. SCIADEPIIO'

- Page 1032 and 1033: 1014 SEISACIITHEIA. SELLA. was sold

- Page 1034 and 1035: 1016 SENATUS. SENATUS. conjecture t

- Page 1036 and 1037: loin SENATUS. SENATUS. kings into t

- Page 1038 and 1039: 1020 SENATUS. SENATUS. before the s

- Page 1040 and 1041: 1022 SKNATUS. SENATUSCONSULTUM. in

- Page 1042 and 1043: 1021 SENATUSCONSULTUM. SENATUSCONSU

- Page 1044 and 1045: Nkronianum, also called Pisonianum,

- Page 1046 and 1047: SEPTA. [Comitia, p. 336, b.] SEPTEM

- Page 1048 and 1049: 1030 SERTA. SERVITUTES. and of frui

- Page 1050 and 1051: 1032 SERVITUTES. SERVITUTES. to get

- Page 1052 and 1053: 1034 servus. SERVUS. mutual interes

- Page 1054 and 1055: armies ; the battles of Marathon an

- Page 1056 and 1057: 1038 SERVUS. SERVUS. without the kn

- Page 1058 and 1059: 1040 SERVUS. SERVUS. three thousand

- Page 1060 and 1061: 1042 SERVES. SESTERTIUS. year. They

- Page 1062 and 1063: 10-14 SIBYLLINI LIBRI. SIGNA MILITA

- Page 1064 and 1065: 101C SISTRUM. S1TOPHYLACES. Cant. v

- Page 1066 and 1067: 1048 SITOU DIKE. soccus. payable on

- Page 1068 and 1069: lO.iO SOCII. tidcred equivalent, it

- Page 1070 and 1071: 1052 SPECULUM. SPECULUM. 14.) The n

- Page 1072 and 1073: t054 SPOLIA. SPORTULA. riots, stand

- Page 1074 and 1075: 1056 STADIUM. STATER. HSXixos 8p&no

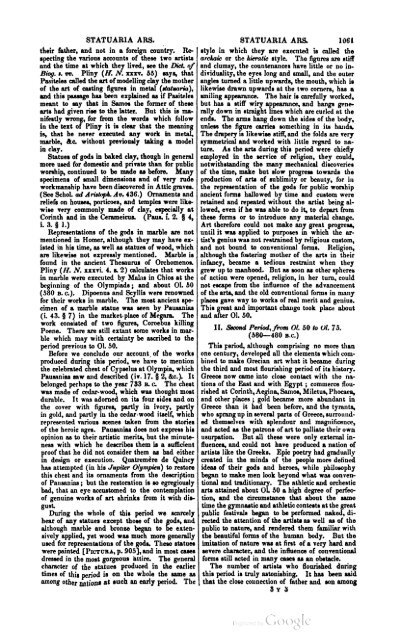

- Page 1076 and 1077: 1088 STATUARIA ARS. STATUARIA ARS.

- Page 1080 and 1081: 1063 STATUARIA ARS. STATUARIA ARS.

- Page 1082 and 1083: 1064 STATUARIA ARS. STATUARIA ARS.

- Page 1084 and 1085: 1066 STATUARIA ARS. STATUARIA ARS.

- Page 1086 and 1087: 1068 STATUARIA ARS. STATUARIA ARS.

- Page 1088 and 1089: 1070 STATUARIA AKS. STATUARIA ARS.

- Page 1090 and 1091: 1072 STIPENDIUM. STIPENDICM. during

- Page 1092 and 1093: 1074 STRATEOUS. STRATORES. the peop

- Page 1094 and 1095: 1076 SUCCESSIO. SUFFRAGIUM. called

- Page 1096 and 1097: 1078 SUPERFICIES. SUPERFICIES. Juli

- Page 1098 and 1099: loflO SYLAK. Steph. ; Dem. de Cor.

- Page 1100 and 1101: 1002 SYMPOSIUM, SYMPOSIUM. that the

- Page 1102 and 1103: 1084 SYNDICS. SYNEGORUS. Respecting

- Page 1104 and 1105: 1086 SYNEGORUS. 8YNGRAPHE. and woul

- Page 1106 and 1107: SYRINX. SYSSITIA. SYRINX (ffiWUthe

- Page 1108 and 1109: 1000 SYSSITIA. TA BELLA. vacancies

- Page 1110 and 1111: 1093 TABULAE. TABULARIUM. that they

- Page 1112 and 1113: 1094 TAGUS. TALAHIA. same Scopasas

- Page 1114 and 1115: 1096 TAMIAS. TAMIAS. of the feast w

- Page 1116 and 1117: 1098 TEG L LA. TEGULA. special sign

- Page 1118 and 1119: ItOO TELA. TELA. of Hera, and to be

- Page 1120 and 1121: 110-2 TELA. TELONE& object ; and, a

- Page 1122 and 1123: 1104 TEMPLUM. TEMPLUM. piece of lan

- Page 1124 and 1125: 1106 TEMPLUM. TEMPLUM. lumni on the

- Page 1126 and 1127: 1108 TEMPLUM. TEMPLUM. V. Dipteral

- Page 1128 and 1129:

1110 TKMI'LUM. TEMPLUM. along each

- Page 1130 and 1131:

1112 TERMINALIA. TESSERA. 4913 B. c

- Page 1132 and 1133:

1114 TESTAMENTI'M. TESTAMENTUM. dri

- Page 1134 and 1135:

1116 TESTAMENTUM. TESTAMENTUM. per

- Page 1136 and 1137:

1118 TESTAMENTUM. TESTVDO. or pract

- Page 1138 and 1139:

1120 THARGELIA. THEATRCM. THALLO'PH

- Page 1140 and 1141:

112-3 THEATUUM. THEATRUM. persons m

- Page 1142 and 1143:

J 124 TIIEATItUM. THEATRUM. Vcrslch

- Page 1144 and 1145:

1126 THKORICA. TIIEORICA. that went

- Page 1146 and 1147:

1128 THESMOPHORIA. THOLUS. from Egy

- Page 1148 and 1149:

1130 TIARA. TIBIA. I variegated wit

- Page 1150 and 1151:

1132 TIMEMA. TIMEMA. in the laws in

- Page 1152 and 1153:

1134 TITHENIDIA. TOGAtm ono of Sir

- Page 1154 and 1155:

Hit TOGA. TOGA. that dignity which

- Page 1156 and 1157:

trod the grapes together. To ** tre

- Page 1158 and 1159:

The head in the preceding woodcut i

- Page 1160 and 1161:

114-2 TRAGOEDIA. TRAGOEDIA. sprang

- Page 1162 and 1163:

1144 TRAGOEDIA. TRAGOEDIA. plays as

- Page 1164 and 1165:

haa no choral ode after it. Of the

- Page 1166 and 1167:

1148 TRIBULA. TRIBUNUS. unnatural,

- Page 1168 and 1169:

1150 TBIBUNUS. TMBUNUS. the plebs,

- Page 1170 and 1171:

iv. 9 ; Plin. EpisL L 23, ix. 13 ;

- Page 1172 and 1173:

] 1.14 TRIBUS. TRIDU5. to hare been

- Page 1174 and 1175:

1156 TRIBUS. TRIBUTUM. twenty by th

- Page 1176 and 1177:

1158 TRICLINIUM. TRIERARCIIIA. in o

- Page 1178 and 1179:

1160 TMERARCHIA. TRIERARCH IA. tint

- Page 1180 and 1181:

M62 TRIKRARCHIA. TRIPOS. viii. 116)

- Page 1182 and 1183:

11G4 TRIUMPH US. TRIUMPUUS. Such di

- Page 1184 and 1185:

Ilea TRIUMPHUS. TR1UMPHUS. headed b

- Page 1186 and 1187:

1168 TRIUMVIRI. TROPAEUM. slaves an

- Page 1188 and 1189:

1170 TRUTINA. TUBA. when they were

- Page 1190 and 1191:

1172 TUNICA. TUNICA. torn. (Compare

- Page 1192 and 1193:

1174 TUNICA. TURRIS. (Apnl. Florvt.

- Page 1194 and 1195:

J 176 TUTOR. TUTOR. were placed on

- Page 1196 and 1197:

1178 TUTOR. TUTOR. wu enough, if he

- Page 1198 and 1199:

HBO TYMPANUM. TYMPANUM. the particu

- Page 1200 and 1201:

1182 TYRANNUS. TYRANNIDOS GRAPH& Am

- Page 1202 and 1203:

1184 VECTIGAL1A. VECTIGALIA- 40, ni

- Page 1204 and 1205:

1186 VKNABULUM. VENATIO. they rose

- Page 1206 and 1207:

I 1188 VKNRFICMTM. VENEFICIUM. thir

- Page 1208 and 1209:

1190 VKSTALES. VESTALES. b\ Domii.

- Page 1210 and 1211:

1 19-2 VIAK VIAE. been compelled to

- Page 1212 and 1213:

1194 VIAE. VIAE. most important bra

- Page 1214 and 1215:

censors, and the aedilet. They were

- Page 1216 and 1217:

11.'in VINDICATIO. VINDICATIO. of t

- Page 1218 and 1219:

1200 VINMCTA. VIXEA. either by the

- Page 1220 and 1221:

120*2 VINUM. VIXUM. and the whole a

- Page 1222 and 1223:

1:04 VI NUM. VINUM. shown In the il

- Page 1224 and 1225:

1206 VIXUM. VISUM. not conducted wi

- Page 1226 and 1227:

1*200 VINUM. VIXUM. e.) to the Prir

- Page 1228 and 1229:

1210 V1TRUM. VITRUM. pctent judges

- Page 1230 and 1231:

1212 V1TTA. VITTA. angles to th« d

- Page 1232 and 1233:

1214 UNGUEXTA. UNIVERS1TAShour. fAs

- Page 1234 and 1235:

1.216 UNIVERSITAS. UNIVERSITAS. of

- Page 1236 and 1237:

1218 USUCAPIO. USUCAPIO. the Twelve

- Page 1238 and 1239:

1220 USUCAPIO. VSUCAPIO. declared t

- Page 1240 and 1241:

1222 USUSFRUCTUS. XENELASIA. nify t

- Page 1242 and 1243:

1224 ZETETAE. ZONA. look from the m

- Page 1244 and 1245:

TABLES OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES.

- Page 1246 and 1247:

TABLES OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES. Inc

- Page 1248 and 1249:

I'230 TABLES OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURE

- Page 1250 and 1251:

123i TABLES OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES

- Page 1252 and 1253:

1234 TABLES OF WEIGHTS AND MEASUREa

- Page 1254 and 1255:

I r-'.ir; TABLES OF WEIGHTS AND MEA

- Page 1256 and 1257:

123S TABLES OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES

- Page 1258 and 1259:

1240 TABLES OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES

- Page 1260 and 1261:

I N D E X. The numerals indicate th

- Page 1262 and 1263:

1244 INDEX. tAtnr^(7oy, 'AiTKi'Aioi

- Page 1264 and 1265:

1346 INDEX. Aiktj avp.So\aitavt or

- Page 1266 and 1267:

1248 INDEX. 'H/iiprc, or 'H.uVa, 36

- Page 1268 and 1269:

1250 INDEX. Kbttj, 239, a ; 788. a.

- Page 1270 and 1271:

1252 INDEX. Oi'.paWo, 918, b. Ovpid

- Page 1272 and 1273:

1254 INDEX. 'P&rrpor, 627, a. 'PvKi

- Page 1274 and 1275:

1256 INDEX. YmMrar, 1138, b. 'Tio(

- Page 1276 and 1277:

1258 INDEX. Adgnati, 309, a. Adgria

- Page 1278 and 1279:

1260 INDEX. Augustalia, 179, b. Aug

- Page 1280 and 1281:

1262 INDEX. Codex Gregorianus et He

- Page 1282 and 1283:

I2C4 Dcsultor, 394, b. Detestatio s

- Page 1284 and 1285:

1866 INDEX. Fritillus, 548, b. Fron

- Page 1286 and 1287:

1868 INDEX. Jure cossio, in, 653, a

- Page 1288 and 1289:

mo Ui regis, G9T, a; 1149,1. regiae

- Page 1290 and 1291:

1272 INDEX. Natatio, 189, b; 195, a

- Page 1292 and 1293:

1274 INDEX. Plautia, or Plotia lex

- Page 1294 and 1295:

1276 INDEX. Re* immobile*, 491, b.

- Page 1296 and 1297:

1878 INDEX. Stadium, 1055, a. Stala

- Page 1298 and 1299:

12RO Vergilianum tidus, 150, «. Ve

- Page 1300 and 1301:

1282 INDEX. Kn»ign«, military, 10

- Page 1302 and 1303:

CLASSIFIED INDEX. Under each head t

- Page 1304 and 1305:

1386 INDEX. Dress, Set. — continu

- Page 1306 and 1307:

1388 INDEX, Income, &c. — incs, &

- Page 1308 and 1309:

1290 INDEX. Music, Sec. — continu

- Page 1310 and 1311:

1292 INDEX. Roman I-aw - Roman I-aw

- Page 1312:

miHTKD BT SI'OTTISWOODE UD CO. HKW-

- Page 1317:

This book should be returned to the