EUROHEALTH

Eurohealth-volume22-number2-2016

Eurohealth-volume22-number2-2016

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

20<br />

Moving towards universal health coverage<br />

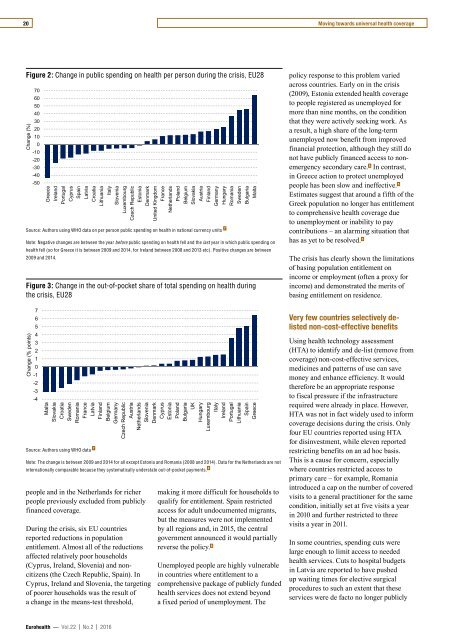

Figure 2: Change in public spending on health per person during the crisis, EU28<br />

Change (%)<br />

70<br />

60<br />

50<br />

40<br />

30<br />

20<br />

10<br />

0<br />

-10<br />

-20<br />

-30<br />

-40<br />

-50<br />

Greece<br />

Ireland<br />

Portugal<br />

Cyprus<br />

Spain<br />

Latvia<br />

Croatia<br />

Lithuania<br />

Italy<br />

Slovenia<br />

Luxembourg<br />

Source: Authors using WHO data on per person public spending on health in national currency units 7<br />

Czech Republic<br />

Estonia<br />

Note: Negative changes are between the year before public spending on health fell and the last year in which public spending on<br />

health fell (so for Greece it is between 2009 and 2014, for Ireland between 2008 and 2013 etc). Positive changes are between<br />

2009 and 2014.<br />

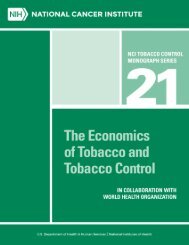

Figure 3: Change in the out-of-pocket share of total spending on health during<br />

the crisis, EU28<br />

Change (% points)<br />

7<br />

6<br />

5<br />

4<br />

3<br />

2<br />

1<br />

0<br />

-1<br />

-2<br />

-3<br />

-4<br />

Malta<br />

Slovakia<br />

Croatia<br />

Sweden<br />

Romania<br />

France<br />

Latvia<br />

Source: Authors using WHO data 7<br />

Finland<br />

Belgium<br />

Germany<br />

Czech Republic<br />

Austria<br />

Netherlands<br />

people and in the Netherlands for richer<br />

people previously excluded from publicly<br />

financed coverage.<br />

Denmark<br />

Slovenia<br />

During the crisis, six EU countries<br />

reported reductions in population<br />

entitlement. Almost all of the reductions<br />

affected relatively poor households<br />

(Cyprus, Ireland, Slovenia) and noncitizens<br />

(the Czech Republic, Spain). In<br />

Cyprus, Ireland and Slovenia, the targeting<br />

of poorer households was the result of<br />

a change in the means-test threshold,<br />

United Kingdom<br />

Denmark<br />

Note: The change is between 2009 and 2014 for all except Estonia and Romania (2008 and 2014). Data for the Netherlands are not<br />

internationally comparable because they systematically understate out-of-pocket payments. 8<br />

France<br />

Cyprus<br />

Netherlands<br />

Estonia<br />

Poland<br />

Poland<br />

Belgium<br />

Bulgaria<br />

Slovakia<br />

UK<br />

Austria<br />

Hungary<br />

Finland<br />

Luxembourg<br />

Germany<br />

Italy<br />

Hungary<br />

Ireland<br />

Romania<br />

Portugal<br />

Sweden<br />

Lithuania<br />

Bulgaria<br />

Spain<br />

Malta<br />

Greece<br />

making it more difficult for households to<br />

qualify for entitlement. Spain restricted<br />

access for adult undocumented migrants,<br />

but the measures were not implemented<br />

by all regions and, in 2015, the central<br />

government announced it would partially<br />

reverse the policy. 6<br />

Unemployed people are highly vulnerable<br />

in countries where entitlement to a<br />

comprehensive package of publicly funded<br />

health services does not extend beyond<br />

a fixed period of unemployment. The<br />

policy response to this problem varied<br />

across countries. Early on in the crisis<br />

(2009), Estonia extended health coverage<br />

to people registered as unemployed for<br />

more than nine months, on the condition<br />

that they were actively seeking work. As<br />

a result, a high share of the long-term<br />

unemployed now benefit from improved<br />

financial protection, although they still do<br />

not have publicly financed access to nonemergency<br />

secondary care. 5 In contrast,<br />

in Greece action to protect unemployed<br />

people has been slow and ineffective. 5<br />

Estimates suggest that around a fifth of the<br />

Greek population no longer has entitlement<br />

to comprehensive health coverage due<br />

to unemployment or inability to pay<br />

contributions – an alarming situation that<br />

has as yet to be resolved. 5<br />

The crisis has clearly shown the limitations<br />

of basing population entitlement on<br />

income or employment (often a proxy for<br />

income) and demonstrated the merits of<br />

basing entitlement on residence.<br />

Very few countries selectively delisted<br />

non-cost-effective benefits<br />

Using health technology assessment<br />

(HTA) to identify and de-list (remove from<br />

coverage) non-cost-effective services,<br />

medicines and patterns of use can save<br />

money and enhance efficiency. It would<br />

therefore be an appropriate response<br />

to fiscal pressure if the infrastructure<br />

required were already in place. However,<br />

HTA was not in fact widely used to inform<br />

coverage decisions during the crisis. Only<br />

four EU countries reported using HTA<br />

for disinvestment, while eleven reported<br />

restricting benefits on an ad hoc basis.<br />

This is a cause for concern, especially<br />

where countries restricted access to<br />

primary care – for example, Romania<br />

introduced a cap on the number of covered<br />

visits to a general practitioner for the same<br />

condition, initially set at five visits a year<br />

in 2010 and further restricted to three<br />

visits a year in 2011.<br />

In some countries, spending cuts were<br />

large enough to limit access to needed<br />

health services. Cuts to hospital budgets<br />

in Latvia are reported to have pushed<br />

up waiting times for elective surgical<br />

procedures to such an extent that these<br />

services were de facto no longer publicly<br />

Eurohealth — Vol.22 | No.2 | 2016