EUROHEALTH

Eurohealth-volume22-number2-2016

Eurohealth-volume22-number2-2016

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Moving towards universal health coverage<br />

25<br />

Population<br />

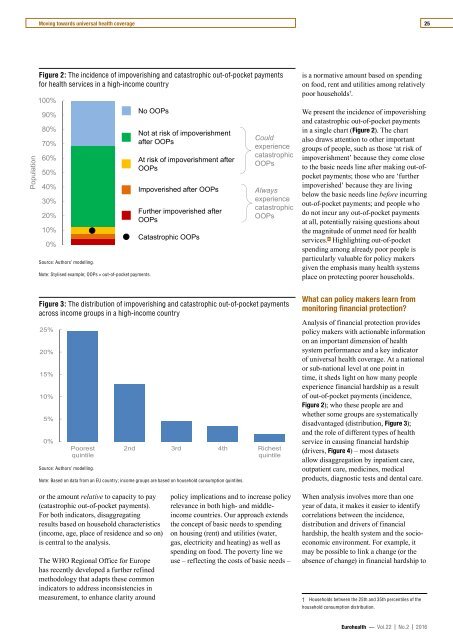

Figure 2: The incidence of impoverishing and catastrophic out-of-pocket payments<br />

for health services in a high-income country<br />

100%<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

Source: Authors’ modelling.<br />

Note: Stylised example; OOPs = out-of-pocket payments.<br />

No OOPs<br />

Not at risk of impoverishment<br />

after OOPs<br />

At risk of impoverishment after<br />

OOPs<br />

Impoverished after OOPs<br />

Further impoverished after<br />

OOPs<br />

Catastrophic OOPs<br />

Could<br />

experience<br />

catastrophic<br />

OOPs<br />

Always<br />

experience<br />

catastrophic<br />

OOPs<br />

is a normative amount based on spending<br />

on food, rent and utilities among relatively<br />

poor households † .<br />

We present the incidence of impoverishing<br />

and catastrophic out-of-pocket payments<br />

in a single chart (Figure 2). The chart<br />

also draws attention to other important<br />

groups of people, such as those ‘at risk of<br />

impoverishment’ because they come close<br />

to the basic needs line after making out-ofpocket<br />

payments; those who are ‘further<br />

impoverished’ because they are living<br />

below the basic needs line before incurring<br />

out-of-pocket payments; and people who<br />

do not incur any out-of-pocket payments<br />

at all, potentially raising questions about<br />

the magnitude of unmet need for health<br />

services. 6 Highlighting out-of-pocket<br />

spending among already poor people is<br />

particularly valuable for policy makers<br />

given the emphasis many health systems<br />

place on protecting poorer households.<br />

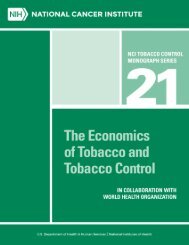

Figure 3: The distribution of impoverishing and catastrophic out-of-pocket payments<br />

across income groups in a high-income country<br />

25%<br />

20%<br />

15%<br />

10%<br />

5%<br />

0%<br />

Poorest<br />

quintile<br />

Source: Authors’ modelling.<br />

2nd 3rd 4th Richest<br />

quintile<br />

Note: Based on data from an EU country; income groups are based on household consumption quintiles.<br />

What can policy makers learn from<br />

monitoring financial protection?<br />

Analysis of financial protection provides<br />

policy makers with actionable information<br />

on an important dimension of health<br />

system performance and a key indicator<br />

of universal health coverage. At a national<br />

or sub-national level at one point in<br />

time, it sheds light on how many people<br />

experience financial hardship as a result<br />

of out-of-pocket payments (incidence,<br />

Figure 2); who these people are and<br />

whether some groups are systematically<br />

disadvantaged (distribution, Figure 3);<br />

and the role of different types of health<br />

service in causing financial hardship<br />

(drivers, Figure 4) – most datasets<br />

allow disaggregation by inpatient care,<br />

outpatient care, medicines, medical<br />

products, diagnostic tests and dental care.<br />

or the amount relative to capacity to pay<br />

(catastrophic out-of-pocket payments).<br />

For both indicators, disaggregating<br />

results based on household characteristics<br />

(income, age, place of residence and so on)<br />

is central to the analysis.<br />

The WHO Regional Office for Europe<br />

has recently developed a further refined<br />

methodology that adapts these common<br />

indicators to address inconsistencies in<br />

measurement, to enhance clarity around<br />

policy implications and to increase policy<br />

relevance in both high- and middleincome<br />

countries. Our approach extends<br />

the concept of basic needs to spending<br />

on housing (rent) and utilities (water,<br />

gas, electricity and heating) as well as<br />

spending on food. The poverty line we<br />

use – reflecting the costs of basic needs –<br />

When analysis involves more than one<br />

year of data, it makes it easier to identify<br />

correlations between the incidence,<br />

distribution and drivers of financial<br />

hardship, the health system and the socioeconomic<br />

environment. For example, it<br />

may be possible to link a change (or the<br />

absence of change) in financial hardship to<br />

† Households between the 25th and 35th percentiles of the<br />

household consumption distribution.<br />

Eurohealth — Vol.22 | No.2 | 2016