Preservings 11 (1997) - Plett Foundation

Preservings 11 (1997) - Plett Foundation

Preservings 11 (1997) - Plett Foundation

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Preservings</strong><br />

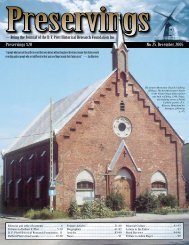

The worship house of the Bergthal Colony situated in the central village of Bergthal could seat 1000 people.<br />

Dimensions 40 by 100 feet. The cross and bell tower were added after 1876. Photo courtesy of The Bergthal<br />

Colony, page 37.<br />

Peter Unger (1812-88) BGB A10, born in Einlage,<br />

Chortitza Colony, who settled in the village of<br />

Bergthal, Bergthal Colony, Russia. Unger also received<br />

a gold watch from the Imperial Czar “for<br />

services during the Crimean War.” Unger must<br />

have been an intelligent and educated man as he<br />

was the District (Municipal) Secretary at the<br />

time—Oberschulz, page 29. Unger immigrated<br />

to Canada in 1876 and established the “estate”<br />

Felsenton on NE22-6-6E and NW23-6-6E, just<br />

south of Steinbach. Unger had 22 children and<br />

was the ancestor of the “Felsenton” Ungers.<br />

A third gold watch for honourable service during<br />

the Crimean War was received by Abraham<br />

Hiebert, Schönthal, also listed as district secretary.<br />

Each watch was worth 150 ruble, more or<br />

less equal to six good horses. Only four watches<br />

of this value were awarded to individuals in the<br />

Molotschna and Chortitza Colonies altogether, although<br />

<strong>11</strong> watches of lessor values were awarded<br />

including one to Samuel Kleinsasser, from<br />

Hutterthal, a Hutterite.<br />

Bergthal also had colourful residents such as<br />

Johann Schroeder (1807-84), who served as<br />

“chief-of-police, fire chief and at times social<br />

worker and marriage councillor.” When his second<br />

wife died, Johann was preparing to go courting<br />

for another wife. His maid, Maria Dyck (1840-<br />

1900), an intelligent woman, stood at the door<br />

watching these preparations and won his heart<br />

by quoting some lines of Goethe’s poetry to him,<br />

`... Sieh das Gute liegt so nah’”; see Wm.<br />

Schroeder, <strong>Preservings</strong>, No. 8, June 1996, Part<br />

One, pages 44-46.<br />

Bergthal Schools.<br />

Each village in Bergthal had its own centrally<br />

located school house. The teachers were often local<br />

individuals who had a gift and interest in teaching<br />

the young, but were also hired from the<br />

Molotschna and Chortitza Colonies. Teaching<br />

methods followed those standard at the time.<br />

The teachers in the Bergthal Colony in 1848<br />

were as follows: Bergthal - Heinrich Wiens<br />

(Gerhard Dueck); Schönfeld - Abraham Friesen<br />

(Abraham Enns); Schönthal - Franz Dyck (Corn.<br />

Neufeld); Heuboden - Abraham Wiebe (Johann<br />

Hiebert); and Friedrichsthal - (Johann Buhler)—<br />

Oberschulz, page 121. The second name listed in<br />

brackets may have been a substitute or teacher<br />

trainee. The Bergthal Colony teachers 1857 were:<br />

Bergthal - Gerhard Dueck; Schönfeld - Abraham<br />

Ens; Schönthal - Cornelius Neufeld; and<br />

Heuboden - Johann Hiebert—Oberschulz, page<br />

22.<br />

The Bergthal teachers were genuinely interested<br />

in the well-being and spiritual growth of<br />

their students. In some cases among conservative<br />

Mennonites teaching was a stepping stone to leadership<br />

in the Gemeinde. This also held true among<br />

the Bergthaler as with David Stoesz, who taught<br />

in Friedrichsthal and later became Aeltester of<br />

the Chortitzer Gemeinde in 1882.<br />

The philosophy of education of conservative<br />

Mennonites was that schools should instill children<br />

with “Genuine faith ... before the forces of<br />

reason take hold and prevent a true understanding<br />

of `simplicity in Christ’.” The purpose of the<br />

school system was not necessarily to excel in the<br />

mechanics of learning, but rather “to prepare the<br />

youth to live an existential Christian life of piety<br />

and reverence for God based on simplicity and<br />

love for fellowman. A good education opened a<br />

child’s heart to allow a knowledge of Christ to<br />

take root.”<br />

Whatever belonged to higher education was<br />

seen as leading to “sophistry, unbelief, and corruption<br />

of the church, for knowledge puffeth up.<br />

1 Cor. 8:1.”<br />

The truth of this statement was observed in<br />

many from among the Russian Mennonites such<br />

as historian Peter M. Friesen who attended Separatist-Pietist<br />

Bible Schools in Europe and elsewhere<br />

and returned to their home communities<br />

filled with disdain for their traditional faith and<br />

who commenced fervent proselytising for all<br />

manner of “fabled” endtimes teachings based on<br />

the novels of Jung Stilling who believed that the<br />

Second Coming would occur in the east and that<br />

the Imperial Czar would be the saviour of the<br />

Church in the end-times (Note Two). It was fortunate<br />

for these people that they preached extemporaneously<br />

as had they carefully composed and<br />

written out their sermons as conservative ministers<br />

did, their descendants would be extremely<br />

embarrassed at the teachings they propagated so<br />

fanatically which were proven totally false by the<br />

effluxion of time.<br />

4<br />

The educational system in Bergthal has been<br />

unfairly criticized often by writers committed to<br />

modernization typology or by those whose religious<br />

disposition made it necessary for them to<br />

denigrate conservative and orthodox Mennonites.<br />

It is true that Bergthal was not directly affected<br />

by the reforms of Johann Cornies in the sense<br />

that the schools were never put under his control.<br />

But this was probably more of a blessing than a<br />

disadvantage. Bergthal received many of the benefits<br />

indirectly through the various emigrants arriving<br />

in the new settlement as late as 1853 and<br />

by teachers hired from the outside, from the<br />

Molotschna as well as the Old Colony. e.g. Jakob<br />

Warkentin (b. 1836), Tiege, Mol., Pioneers and<br />

Pilgrims, page 187, and Johann Abrams (1794-<br />

1856), BGB A 58, from Pastwa, Mol., teacher in<br />

Schönfeld 1843.<br />

Advocates of the Cornies reforms conveniently<br />

forget that these measures caused immense social<br />

disruption and disputation when they were<br />

implemented in the Molotschna and Old Colonies,<br />

alienating the majority of the population. In<br />

setting rigid standards Cornies inhibited the creativity<br />

of the best of the old-school teachers and<br />

prohibited traditional Mennonite art forms such<br />

as Schönschrieben and Fraktur which he regarded<br />

as sissified. These advocates also ignore some of<br />

the negative aspects of the post-Cornies pedagogue:<br />

they were known as frightfully strict and<br />

almost abusive disciplinarians, many of their students<br />

became vulnerable to a fawning Russian<br />

nationalism and/or pan-Germanism, many fell<br />

victims to the fanciful teachings of German Separatist-Pietism,<br />

and, worst of all, they disdained<br />

the Plaut-dietsch language and Low German culture<br />

which had once dominated commerce and<br />

socio-economic life in Northern Europe and<br />

around the Baltic Sea during medieval times.<br />

Those who have denounced the Bergthal<br />

schools so completely and thoroughly have obviously<br />

never studied the writings of Bergthal/<br />

Chortitzer leaders and even ordinary lay-people.<br />

The sermons of Aeltester Gerhard Wiebe (1827-<br />

1900) are studded with jewels of Biblical allegory<br />

and reveal a sound exegesis and a truly inspired<br />

faith as enduring today as when they were<br />

written in the 1860s and are far beyond anything<br />

ever conceived by his enemies. The journals of<br />

Chortitzer Aeltester David Stoesz and minister<br />

Heinrich Friesen are concrete proof that the<br />

Bergthal school system turned out graduates who<br />

were not only imbued with a love of Christ, but<br />

also competent writers and gifted thinkers.<br />

Social Services and Mutual Aid.<br />

The spiritual ethos of the Bergthaler/Chortitzer<br />

people was evident in the three paradigms of rural<br />

agrarian communities; family, village and<br />

church. Its faith was put into practice by a myriad<br />

of social services, community mutual aid, and<br />

ethno-cultural activities.<br />

The mutual aid extended from informal activities<br />

such as a Bahrung (“barn raising”), pig<br />

slaughtering bees (“Schwine’s jkast”), nursing and<br />

midwifery services, to more formal institutionalized<br />

structures such as the Waisenamt (“orphan’s<br />

trust office”) which provided for devolution of<br />

estates, investment of orphans’ and widows’<br />

funds, and loans to community members, the