Adventure 234

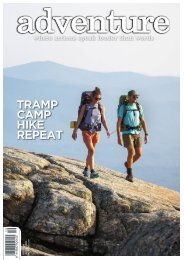

Spring issue of Adventure: Camping and tramping issue

Spring issue of Adventure: Camping and tramping issue

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

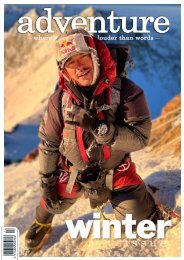

Above: Serenity greets a climber topping out a gendarme in the Central Darrans, northern Fiordland, with the Mt Revelation and<br />

Taiaroa Peak on the left and Mts Underwood and Patuki on the right, above the Taoka Icefall.<br />

The Midi gondola is only one of several in the Chamonix<br />

valley. There’s one that takes you to the top of Le Brévent<br />

(2525m), from where you actually walk downhill for 20<br />

minutes to get to the base of the 300m-high rock climbs.<br />

And the Flégère gondola and Index chairlift deposits you, at<br />

2595m, at the base of the Aiguille Rouge range.<br />

But this also transforms one the world’s best places for alpine<br />

climbing into a complete cluster.<br />

It couldn’t be more different in New Zealand, where it’d be<br />

unusual to see other parties in the country’s best mountains<br />

for alpine rock climbing. The Central Darrans, in northern<br />

Fiordland, encompasses the peaks in the Te Puoho cirque,<br />

as well as those surrounding Lake Turner, including the<br />

ridgeline from Mts Patuki to Madeline. The area is gifted<br />

with vertiginous and glaciated walls of hard rhyolite, which is<br />

much more compact than the schist that dominates most of<br />

the Southern Alps.<br />

But getting there is a tad more challenging than standing<br />

in a gondola bin for 20 minutes. Tales of extreme tramping,<br />

known among Darrans climbers as ‘danger-walking’, is<br />

enough to deter anyone from going there. A couple of friends,<br />

for example, ended up taking their ropes and climbing gear<br />

for a massive walk; they managed to get to the fabled bivvy<br />

cave known as Turner’s Eyrie, but it took them two days and<br />

several close shaves to get there, and they needed the third<br />

day to rest before walking out on day four.<br />

The best way in is a matter of debate, but they all invariably<br />

involve snow and glacial travel, rock scrambling, and the<br />

unique Darrans experience of near-vertical plant-pulling.<br />

Our route - from the Lower Hollyford River to The Eyrie in<br />

one push - was a 17-hour day: bush-bash up to Rainbow<br />

Lake from the Hollyford valley, scramble over a col near Mt<br />

Tuhawaiki, drop under Mt Taiaroa, gain and then negotiate<br />

the Te Puoho Glacier to another col, ease nervously down a<br />

tenuous slope known as Lindsay’s Ledges and, finally, cross<br />

to the Karetai-Patuki col and stumble up the final stretch.<br />

By the time we crawled into The Eyrie, etched into the<br />

northwest side of Mt Karetai, it was 11pm. We were fried. My<br />

climbing partner, Jimmy, only made it through half his dinner<br />

before nodding off, still half-seated in his sleeping bag.<br />

The rewards, though, are immediate. The Eyrie looks out<br />

to the snow-capped towers of Tutoko and Madeline and the<br />

rocky spire of Te Wera. We spent a week exploring, including<br />

twice climbing a 300m-high cliff face, scrambling the south<br />

ridge of Te Wera and the north ridge of Karetai, and reaching<br />

the summit of Mt Underwood via the Taoka Icefall.<br />

And all to ourselves. All I knew in the aftermath of the trip<br />

was that I had to return to such a unique place - the country's<br />

most exquisite, with infinite rock and adventure to be<br />

sampled.<br />

It also made me consider the pros and cons of a lack of<br />

infrastructure. Part of the magic of the Central Darrans is<br />

how empty and wild it is. It would be a completely different<br />

experience if there was gondola access, and crowds of<br />

climbers at the base of every rock wall.<br />

But getting there is no picnic. One of New Zealand’s best<br />

climbers told me he has no inclination to explore the area<br />

because of the walk-climb ratio, as in, heaps of ‘dangerwalking’<br />

and relatively little climbing. I didn’t really understand<br />

until I was in Chamonix, where there are massive clusters of<br />

climbers, but the ratio is flipped.<br />

The advantages were never more starkly obvious than when<br />

my climbing partner and I arrived at the south face of the Midi<br />

one morning. Our stiff elbows had helped us to be the first<br />

ones there, and we started unpacking our climbing gear just<br />

as the sun’s first rays enveloped the tower of granite in front<br />

of us.<br />

My stomach turned nauseous, however, when I realised I’d<br />

left my climbing shoes at home. I sprinted back up the snowy<br />

ridge, took the gondola down, raced through town and up<br />

a hill to our apartment, grabbed my shoes, barreled back<br />

down the hill, and stood in a sweaty mess while catching an<br />

ascending gondola bin.<br />

Where else in the world can you rush home to retrieve a<br />

forgotten item and be back at the base of a granite wall,<br />

3700ish metres above sea level, within an hour?<br />

16//WHERE ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS/#<strong>234</strong>