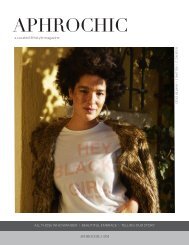

AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 12

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Reference<br />

While Harris does not specifically<br />

propose a “wheel model,” to describe the connection<br />

between Diaspora cultures and the<br />

African continent itself, it is presented here as<br />

an accurate depiction of the relationship as it<br />

is commonly imagined in many constructions<br />

of the Diaspora, including Harris’. And though<br />

this model is easily intuited and not without its<br />

degree of accuracy, the proprietary sentiment<br />

it conveys through such constructions as Africa<br />

and its diaspora, are at the root of several<br />

perspectives that construe the cultures and<br />

peoples of the African Diaspora, not only as descendants<br />

of the African continent but as derivatives<br />

and ultimately possessions.<br />

These suppositions, if not by themselves<br />

openly problematic, at the very least raise<br />

several important questions. Of the various<br />

issues to consider in the proposition of "Africa<br />

and its diaspora," three present themselves<br />

as the most pressing: possession, construction<br />

and position. The first of these, possession,<br />

asks simply, to whom does the African<br />

Diaspora belong?<br />

The African Diaspora or Africa’s Diaspora?<br />

<strong>No</strong> one contends the description, The<br />

African Diaspora and no one should, because<br />

that is what we are. However, there is a subtle<br />

paternalism to the phrase Africa and its<br />

diaspora, born, like the idea of the underlying<br />

African self, of the belief that Africa somehow<br />

holds within it an original culture, of which all<br />

cultures of the external Diaspora are simple<br />

derivatives.<br />

By this logic we may, like all derivatives,<br />

be judged and arranged in order of quality by<br />

the extent to which we display an appropriate<br />

resemblance to our source material — and<br />

we have been, often by ourselves. Arguments<br />

about which cultures are more or less<br />

African have been all too common throughout<br />

the years, fueling, among other things, the<br />

important work of scholars such as Melville<br />

Herskovits, Zora Neale Hurston, and W.E.B.<br />

DuBois, among many others who investigated<br />

connections between various New World<br />

Diaspora and West African cultures in the early<br />

20th century.<br />

Beyond this important work, however,<br />

the paternalistic streak to traditional definitions<br />

of Diaspora has played out in a variety of<br />

ways, most notably economically. For instance,<br />

the definition offered by the African Union describing<br />

the Diaspora as we of African origin<br />

who, regardless of citizenship or nationality,<br />

live outside the continent, goes on to stipulate<br />

our willingness to, “contribute to the development<br />

of the continent and the building of the<br />

African Union,” as part of what qualifies us as<br />

part of the Diaspora. Similarly, in 2010, when<br />

Margaret Kilo, then head of Fragile States<br />

Unit of the African Development Bank was interviewed<br />

about the outcomes of a seminar<br />

entitled, Mobilizing the African Diaspora for<br />

Capacity Building and Development: Focus on<br />

Fragile States, she defined the Diaspora as, “a<br />

human and investment capital pool that can<br />

strongly contribute to the continent’s development.”<br />

Other organizations, such as the African<br />

Diaspora Group, a non-profit focused on<br />

strengthening financial ties between the<br />

Diaspora and the Continent, roots the impetus<br />

for a financial relationship in the cultural need<br />

of those born away from the continent. Like<br />

Harris, this group views the African Diaspora<br />

as stateless, and without a common country of<br />

origin, language, religion, or culture. “Mother<br />

Africa,” The African Diaspora Group thereby<br />

offers, “will help to restore what was lost, [vital<br />

roots, history, and culture,] and the children of<br />

the diaspora will reciprocate by providing the<br />

knowledge and resources that were gained while<br />

away.” Another section of the website suggests<br />

that, “[it] is time for Africans in the diaspora to<br />

break free from their manufactured identities,<br />

and return to knowledge of self as an African.”<br />

As these groups all seek to enact or at least<br />

envision a particular future for the Diaspora, it<br />

is worth interrogating the ways in which they<br />

are constructing the idea, and how they mean<br />

to employ it.<br />

Like a Motherless Child<br />

In each of the examples presented<br />

above, a Triadic Model, similar if not identical<br />

to Harris’ is being employed to envision the<br />

Diaspora as a 3-part relationship between the<br />

Continent, the (descendants of the) dispersed<br />

and their countries of residence — with references<br />

to both family and hierarchy as part of<br />

the structure. The kind of parent-child relationship<br />

these constructions envision between<br />

Africa and the Diaspora makes a certain<br />

amount of intuitive sense. However, “parent-child”<br />

is a hierarchy, and any hierarchical<br />

model of Diaspora must entail a concerning<br />

sense of ethnocentrism while presenting a host<br />

of other problems.<br />

There is a lurking sense of eurocentrism<br />

both in the way the The African Diaspora Group<br />

offers to “restore what was lost,” for people of<br />

the Diaspora — sometimes called “diasporans”<br />

or “diasporeans,” — and its presentment of<br />

“Mother Africa” as a monolithic whole. The first<br />

upholds the European myth of Africa as ahistorical,<br />

suggesting that African culture as it<br />

exists today represents an original from which<br />

Diaspora cultures are derived and to which<br />

they can return. Yet many hundreds of years<br />

have passed between the first dispersions and<br />

where we all are today. “History,” as Stuart<br />

Hall noted, “has intervened,” changing us from<br />

what we were then to what we are now. While<br />

there are many things that contemporary<br />

Africa can offer the Diaspora and vice versa,<br />

going back in time is not among them.<br />

Further, Africa as we know is not a single<br />

entity. It has many nations, languages and ethnicities,<br />

and whether genetically or culturally,<br />

many of us, as diasporeans, are made up of<br />

quite a few of them. Therefore when presented<br />

with the African Diaspora Group’s offer to shed<br />

our, “manufactured identities,” (all identities<br />

are manufactured) “and return to knowledge<br />

of self as an African,” it would be fair of us to<br />

ask, “what type of African should we return to<br />

being? From what nations? Speaking which<br />

languages?” We can further question whether<br />

simply moving to Africa is enough to remake<br />

us as Africans. Do we lose the distinction<br />

of being born in another place and formed<br />

in another culture as soon as we become<br />

residents of an African state? And even if so, is<br />

that something we want? Does the Diaspora,<br />

African Americans, Caribbeans, et al. value its<br />

100 aphrochic