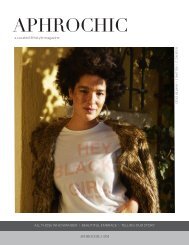

AphroChic Magazine: Issue No. 12

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Reference<br />

cultures — the art, music, fashion, literature, rituals, traditions,<br />

holidays and more — that our ancestors labored for centuries to<br />

build in hostile lands and which we now carry forward? Or are<br />

they as worthless as they’re made to sound — cheap knock-offs<br />

cobbled together just to be cast aside for the genuine article?<br />

if that heritage is truly something that we must purchase or<br />

earn through service, or if our heritage is ours simply because it<br />

is ours? Because if the latter, then no entity, not even Africa, has<br />

the power to grant or deny it to us — and certainly not to hold it<br />

out to us in trade.<br />

Cash-for-Heritage<br />

Perhaps it is because Harris’ Triadic Model so resembles<br />

the specifically commercial “Triangular Trade” that Eric<br />

Williams introduced in his 1944 classic Capitalism and Slavery<br />

that the models presented here all envision the relationship<br />

between Africa and Diaspora in such solidly economic (as<br />

opposed to cultural or even political) terms — or perhaps it’s<br />

just a coincidence. In Williams’ construction, enslaved Africans<br />

were forced to work in New World agriculture to produce raw<br />

materials. Those materials were then shipped to Europe to<br />

become finished goods that were then sold back to European<br />

colonies. Money from the sale of goods was then used to<br />

purchase and enslave more Africans, and so on.<br />

With so much of the history of the Diaspora bound to the<br />

cruel exploitation of Black bodies as both labor and commodities,<br />

it is understandably alarming to those descended from<br />

Africans enslaved for centuries to know that they are regarded<br />

on the one hand by the African Development Bank as “human<br />

and investment capital,” while the African Union regards<br />

Diaspora status as being contingent on our willingness and<br />

ability to contribute to the development of the continent and<br />

the African Union.<br />

While Kilo posits the relationship unilaterally, with the<br />

Diaspora strictly representing a resource for the Continent,<br />

both the African Union and the African Diaspora Group present<br />

it as an exchange — cash-for-heritage — in which contributions<br />

to the Continent are repaid, either with membership in<br />

the Diaspora, and by extension, Africa, or with the recovery of<br />

culture. Both are tantamount to being granted access to one’s<br />

heritage and culture. As before, it’s a position that invites<br />

questions — ones, this time, that we must all, continental or diasporean,<br />

ask ourselves.<br />

Reflecting on Kilo’s statement, we must ask ourselves<br />

if, after all this time, labor and commodities are still all that<br />

the millions of descendants of the trans-Atlantic slave trade<br />

represent to what is being held out as our ostensible homeland?<br />

Or should any version of the relationship between the Diaspora<br />

and the continent take into account the immeasurable amount<br />

of cultural inspiration and intellectual support that has gone<br />

both ways? And should the Diaspora be willing to enter into this<br />

relationship when it is strictly tributary?<br />

Responding to those who would barter with the Diaspora<br />

for its African heritage, diasporeans must likewise ask ourselves<br />

Questions and <strong>No</strong>n-Questions<br />

<strong>No</strong>ne of this is to say that a strong relationship between<br />

the many countries of the African continent and the rest of the<br />

African Diaspora does not, or should not exist, or that that relationship<br />

cannot or should not include financial support to the<br />

continent from without. Moreover, the purpose of these queries<br />

is not to suggest any sense of exploitative intent, ill will or bad<br />

faith on the part of Africa or any governments, financial institutions<br />

or individuals therein. The work of organizations like<br />

the African Diaspora Group and the African Development Bank<br />

is both laudable and vital. These are worthy goals, as suitable<br />

a basis for international cooperation today as they were in the<br />

days of Henry Sylvester Williams and W.E.B. DuBois.<br />

What is in question however is how we choose to see these relationships,<br />

the basis from which we construct them, and whether<br />

they promote unity and shared benefit or offer yet another form of<br />

division and exploitation. Do the constructs of the Diaspora-Continental<br />

relationship presented in these examples truly value the<br />

people, culture, history, contributions and full potential of the<br />

African Diaspora, or are they simply perpetuating old cycles of exploitation?<br />

Are we going to choose to see the cultures and people<br />

of the Diaspora merely as children, derivatives and property of the<br />

African continent, or do we recognize all African and Africa-descended<br />

cultures as equals? And which version is most likely to<br />

benefit all groups moving forward?<br />

Africa (by Itself) Is <strong>No</strong>t the Answer<br />

The danger of answering these questions incorrectly, or<br />

of these constructions as they currently stand, is that they risk<br />

putting us on sides — Africa and the Diaspora — which can<br />

easily become Africa versus the Diaspora. It’s a situation that<br />

doesn’t benefit any of us and yet it’s one that we already find<br />

ourselves in too often, just as we find one part of the Diaspora<br />

versus another, and almost always around some false notion of<br />

hierarchy, authenticity or ownership.<br />

Whether fully internalized or spurred on by outside<br />

interests, it’s never anything more than an unwillingness to<br />

value one another. As we continue to explore our relationships<br />

and what they mean, and Diaspora continues to evolve, we must<br />

learn to move beyond the notions of hierarchy, ownership and<br />

commodification that are even now threatening to tear us apart.<br />

So does the Diaspora “belong” to the Continent? Yes it does. But<br />

the Continent must also belong to the Diaspora. AC<br />

Guitar player in Puerto Rico by Christian Crocker<br />

issue twelve 103