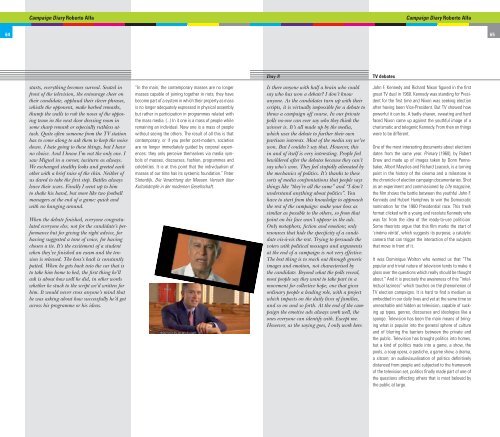

Spots Electorales. El espectáculo de la democracia - Soymenos.net

Spots Electorales. El espectáculo de la democracia - Soymenos.net

Spots Electorales. El espectáculo de la democracia - Soymenos.net

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Campaign Diary Roberto AlfaCampaign Diary Roberto Alfa64 65Day 8TV <strong>de</strong>batesstarts, everything becomes surreal. Seated infront of the television, the entourage cheer ontheir candidate, app<strong>la</strong>ud their clever phrases,whistle the opponent, make barbed remarks,thump the walls to rub the noses of the opposingteam in the next door dressing room insome sharp remark or especially ruthless attack.Quite often someone from the TV stationhas to come along to ask them to keep the noisedown. I hate going to these things, but I haveno choice. And I know I’m not the only one. Isaw Miguel in a corner, taciturn as always.We exchanged stealthy looks and greeted eachother with a brief raise of the chin. Neither ofus dared to take the first step. Battles alwaysleave their scars. Finally I went up to himto shake his hand, but more like two footballmanagers at the end of a game: quick andwith no hanging around.When the <strong>de</strong>bate finished, everyone congratu<strong>la</strong>te<strong>de</strong>veryone else, not for the candidate’s performancebut for giving the right advice, forhaving suggested a tone of voice, for havingchosen a tie. It’s the excitement of a stu<strong>de</strong>ntwhen they’ve finished an exam and the tensionis released. The boss’s back is constantlypatted. When he gets back into the car that isto take him home to bed, the first thing he’l<strong>la</strong>sk is about how well he did, in other wordswhether he stuck to the script we’d written forhim. It would never cross anyone’s mind thathe was asking about how successfully he’d gotacross his programme or his i<strong>de</strong>as.“In the main, the contemporary masses are no longermasses capable of joining together in riots; they havebecome part of a system in which their property as massis no longer a<strong>de</strong>quately expressed in physical assemblybut rather in participation in programmes re<strong>la</strong>ted withthe mass media. (...) In it one is a mass of people whileremaining an individual. Now one is a mass of peoplewithout seeing the others. The result of all this is thatcontemporary, or if you prefer post-mo<strong>de</strong>rn, societiesare no longer immediately gui<strong>de</strong>d by corporal experiences:they only perceive themselves via media symbolsof masses, discourses, fashion, programmes andcelebrities. It is at this point that the individualism ofmasses of our time has its systemic foundation.” PeterSloterdijk, Die Verachtung <strong>de</strong>r Massen. Versuch überKulturkämpfe in <strong>de</strong>r mo<strong>de</strong>rnen Gesellschaft.Is there anyone with half a brain who couldsay who has won a <strong>de</strong>bate? I don’t knowanyone. As the candidates turn up with theirscripts, it is virtually impossible for a <strong>de</strong>bate tothrow a campaign off course. In our privatepolls no-one can ever say who they think thewinner is. It’s all ma<strong>de</strong> up by the media,which uses the <strong>de</strong>bate to further their ownpartisan interests. Most of the media say we’vewon. But I couldn’t say that. However, thisin and of itself is very interesting. People feelbewil<strong>de</strong>red after the <strong>de</strong>bates because they can’tsay who’s won. They feel stupidly alienated bythe mechanics of politics. It’s thanks to thesesorts of media confrontations that people saysthings like “they’re all the same” and “I don’tun<strong>de</strong>rstand anything about politics”. Youhave to start from this knowledge to approachthe rest of the campaign: make your boss assimi<strong>la</strong>r as possible to the others, so from thatpoint on his face won’t appear in the ads.Only metaphors, fiction and emotion; onlyresources that hi<strong>de</strong> the specificity of a candidatevis-à-vis the rest. Trying to persua<strong>de</strong> thevoters with political messages and argumentsat the end of a campaign is not very effective.The best thing is to reach out through genericimages and emotion, not characterised bythe candidate. Beyond what the polls reveal,most people say they want to take part in amovement for collective hope, one that givesordinary people a leading role, with a projectwhich impacts on the daily lives of families,and so on and so forth. At the end of the campaignthe emotive ads always work well, theones everyone can i<strong>de</strong>ntify with. Except me.However, as the saying goes, I only work here.John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon figured in the fi rstgreat TV duel in 1960. Kennedy was standing for Presi<strong>de</strong>ntfor the first time and Nixon was seeking electionafter having been Vice-Presi<strong>de</strong>nt. But TV showed howpowerful it can be. A badly-shaven, sweating and hardfaced Nixon came up against the youthful image of acharismatic and telegenic Kennedy. From then on thingswere to be different.One of the most interesting documents about electionsdates from the same year. Primary (1960), by RobertDrew and ma<strong>de</strong> up of images taken by Donn Pennebaker,Albert Maysles and Richard Leacock, is a turningpoint in the history of the cinema and a milestone inthe chronicle of election campaign documentaries. Shotas an experiment and commissioned by Life magazine,the film shows the battle between the youthful John F.Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey to win the Democraticnomination for the 1960 Presi<strong>de</strong>ntial race. This freshformat clicked with a young and resolute Kennedy whowas far from the i<strong>de</strong>a of the ready-to-use politician.Some theorists argue that this film marks the start of‘cinéma vérité’, which suggests its purpose; a catalyticcamera that can trigger the interaction of the subjectsthat move in front of it.It was Dominique Wolton who warned us that “Thepopu<strong>la</strong>r and trivial nature of television tends to make itgloss over the questions which really should be thoughtabout.” And it is precisely the awareness of this “intellectual<strong>la</strong>ziness” which touches on the phenomenon ofTV election campaigns. It is hard to find a medium soembed<strong>de</strong>d in our daily lives and yet at the same time sounreachable and hid<strong>de</strong>n as television, capable of suckingup types, genres, discourses and i<strong>de</strong>ologies like asponge. Television has been the main means of bringingwhat is popu<strong>la</strong>r into the general sphere of cultureand of blurring the barriers between the private andthe public. Television has brought politics into homes,but a kind of politics ma<strong>de</strong> into a game, a show, thepools, a soap opera, a pastiche, a game show, a drama,a sitcom; an audiovisualisation of politics <strong>de</strong>finitivelydistanced from people and subjected to the frameworkof the television set, politics finally ma<strong>de</strong> part of one ofthe questions affecting others that is most beloved bythe public at <strong>la</strong>rge.