The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville - Pot-pourri

The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville - Pot-pourri

The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville - Pot-pourri

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

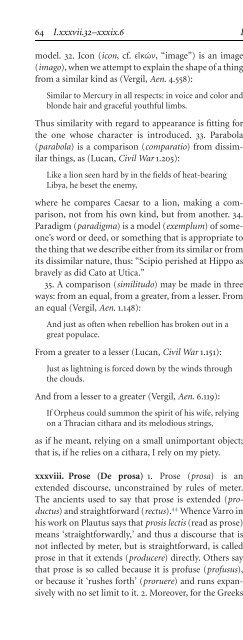

64 I.xxxvii.32–xxxix.6 <strong>Isidore</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Seville</strong><br />

model. 32. Icon(icon, cf. , “image”) is an image<br />

(imago), when we attempt to explain the shape <strong>of</strong> a thing<br />

from a similar kind as (Vergil, Aen. 4.558):<br />

Similar to Mercury in all respects: in voice and color and<br />

blonde hair and graceful youthful limbs.<br />

Thus similarity with regard to appearance is fitting for<br />

the one whose character is introduced. 33. Parabola<br />

(parabola) isacomparison (comparatio) fromdissimilar<br />

things, as (Lucan, Civil War 1.205):<br />

Like a lion seen hard by in the fields <strong>of</strong> heat-bearing<br />

Libya, he beset the enemy,<br />

where he compares Caesar to a lion, making a comparison,<br />

not from his own kind, but from another. 34.<br />

Paradigm (paradigma)isamodel(exemplum)<strong>of</strong>someone’s<br />

word or deed, or something that is appropriate to<br />

the thing that we describe either from its similar or from<br />

its dissimilar nature, thus: “Scipio perished at Hippo as<br />

bravely as did Cato at Utica.”<br />

35. Acomparison (similitudo) maybemadein three<br />

ways: from an equal, from a greater, from a lesser. From<br />

an equal (Vergil, Aen. 1.148):<br />

And just as <strong>of</strong>ten when rebellion has broken out in a<br />

great populace.<br />

From a greater to a lesser (Lucan, Civil War 1.151):<br />

Just as lightning is forced down by the winds through<br />

the clouds.<br />

And fromalesser to a greater (Vergil, Aen. 6.119):<br />

If Orpheus could summon the spirit <strong>of</strong> his wife, relying<br />

on a Thracian cithara and its melodious strings,<br />

as if he meant, relying on a small unimportant object;<br />

that is, if he relies on a cithara, I rely on my piety.<br />

xxxviii. Prose (De prosa) 1. Prose (prosa) is an<br />

extended discourse, unconstrained by rules <strong>of</strong> meter.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ancients used to say that prose is extended (productus)andstraightforward<br />

(rectus). 44 Whence Varro in<br />

his work on Plautus says that prosis lectis (read asprose)<br />

means ‘straightforwardly,’ and thus a discourse that is<br />

not inflected by meter, but is straightforward, is called<br />

prose in that it extends (producere) directly.Others say<br />

that prose is so called because it is pr<strong>of</strong>use (pr<strong>of</strong>usus),<br />

or because it ‘rushes forth’ (proruere) and runs expansively<br />

with no set limit to it. 2.Moreover,forthe Greeks<br />

as well as the Romans, the interest in poems was far<br />

more ancient than in prose, for at first all things used<br />

to be set in verse, and enthusiasm for prose flourished<br />

later. Among the Greeks, Pherecydes <strong>of</strong> Syros was first to<br />

write with unmetered speech, and among the Romans,<br />

Appius Caecus, in his oration against Pyrrhus, was first<br />

to use unmetered speech. Straightway after this, others<br />

competed by means <strong>of</strong> eloquence in prose.<br />

xxxix. Meters (De metris) 1. Meters(metrum) areso<br />

called because they are bounded by the fixed measures<br />

(mensura)andintervals <strong>of</strong> feet, and they do not proceed<br />

beyond the designated dimension <strong>of</strong> time – for measure<br />

is called in Greek. 2.Verses are so called because<br />

when they are arranged in their regular order into feet<br />

they are governed within a fixed limit through segments<br />

that are called caesurae (caesum) andmembers (membrum).<br />

Lest these segments roll on longer than good<br />

judgment could sustain, reason has established a measure<br />

from which the verse should be turned back; from<br />

this ‘verse’ (versus) itself is named, because it is turned<br />

back (revertere, ppl. reversus). 3. Andrelated to this is<br />

rhythm (rhythmus), which is not governed by a specific<br />

limit, but nevertheless proceeds regularly with ordered<br />

feet. In Latin this is called none other than ‘number’<br />

(numerus), regarding which is this (Vergil, Ecl. 9.45):<br />

Irecall the numbers (numerus), if I could grasp the<br />

words!<br />

4.Whateverhasmetric feet is called a ‘poem’ (carmen).<br />

People suppose that the name was given to it either<br />

because it was pronounced ‘in pieces’ (carptim), just as<br />

today we say that wool that the scourers tear in pieces is<br />

carded (carminare), or because they used to think that<br />

people who sang those poems had lost (carere) their<br />

minds.<br />

5.Meters are named either after their feet, or after the<br />

topics about which they are written, or after their inventors,<br />

or after those who commonly use them, or after the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> syllables. 6. Metersnamed after feet are, for<br />

example, dactylic, iambic, trochaic, for trochaic meter is<br />

constructed from the trochee, dactylic from the dactyl,<br />

and others similarly from their feet. Meters are named<br />

after number, as hexameter, pentameter, trimeter – as<br />

44 In fact the old form <strong>of</strong> the word prorsus, “straight on,” was<br />

prosus, the source <strong>of</strong> the word prosa.