Tana Delta Irrigation Project, Kenya: An Environmental Assessment

Tana Delta Irrigation Project, Kenya: An Environmental Assessment

Tana Delta Irrigation Project, Kenya: An Environmental Assessment

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Rehabilitation of the <strong>Tana</strong> <strong>Delta</strong> <strong>Irrigation</strong> <strong>Project</strong>, <strong>Kenya</strong>: <strong>An</strong> <strong>Environmental</strong> <strong>Assessment</strong>.<br />

(b) the ‘madzini’ or ‘floodplain’ forest patches further away from the river course and located<br />

within the farmed floodplain.<br />

(c) the ‘gubani’ or ‘bush’ woodlands that characterise the land beyond the floodplain.<br />

Forest use differs amongst the three types: the more mature ‘madzini’ forests are considered<br />

the most important, primarily because they contain species not found in the less mature, riverbank<br />

forest patches. Whilst less used, the ‘gubani’ woodlands are important as a source of<br />

building poles (see Section 1.5. As has been seen in Section 1 of this report, in addition to<br />

their importance in providing basic needs (e.g. firewood), the forests are particularly important<br />

as a traditional coping strategy in regular times of hardship and stress.<br />

Traditional authority of the forests lies with the GASA – the Pokomo Elders Council, a general<br />

body in which traditional Pokomo law is vested, who implement and enforce traditional law<br />

through GASA representatives within each village. All forests continue to be governed by a<br />

similar set of rules and regulations. However, more recently it is the government Forest<br />

Government that has official jurisdiction over these forests – administered through its local<br />

office in Garsen.<br />

B. Recent Dynamics/Current Situation<br />

Forests Uses/Benefits<br />

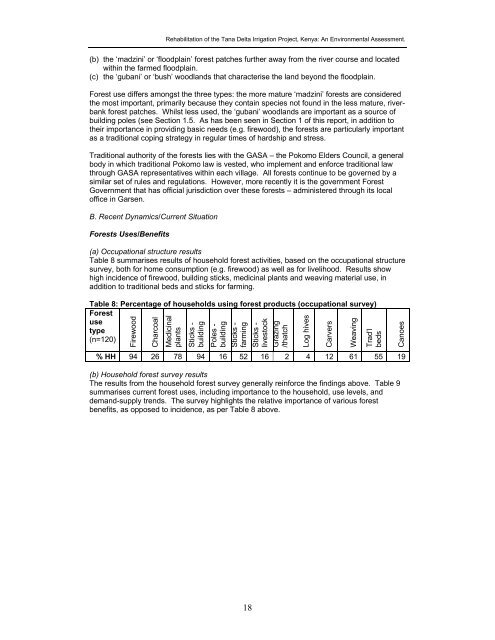

(a) Occupational structure results<br />

Table 8 summarises results of household forest activities, based on the occupational structure<br />

survey, both for home consumption (e.g. firewood) as well as for livelihood. Results show<br />

high incidence of firewood, building sticks, medicinal plants and weaving material use, in<br />

addition to traditional beds and sticks for farming.<br />

Table 8: Percentage of households using forest products (occupational survey)<br />

Forest<br />

use<br />

type<br />

(n=120)<br />

Firewood<br />

Charcoal<br />

Medicinal<br />

plants<br />

Sticks -<br />

building<br />

Poles -<br />

building<br />

Sticks -<br />

farming<br />

Sticks -<br />

livestock<br />

Grazing<br />

/thatch<br />

Log hives<br />

Carvers<br />

Weaving<br />

Trad’l<br />

beds<br />

Canoes<br />

% HH 94 26 78 94 16 52 16 2 4 12 61 55 19<br />

(b) Household forest survey results<br />

The results from the household forest survey generally reinforce the findings above. Table 9<br />

summarises current forest uses, including importance to the household, use levels, and<br />

demand-supply trends. The survey highlights the relative importance of various forest<br />

benefits, as opposed to incidence, as per Table 8 above.<br />

18