EXPLAINING SOCIAL EXCLUSION - Institut für Soziologie

EXPLAINING SOCIAL EXCLUSION - Institut für Soziologie

EXPLAINING SOCIAL EXCLUSION - Institut für Soziologie

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 100<br />

Volume 21 Number 4/5/6 2001 101<br />

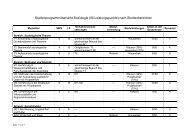

Table 1 (continued):<br />

Predictors of social mobility, pce-model, percentage-effects<br />

Number of preceding<br />

employment history spells<br />

Log-likelihood<br />

Spells<br />

Events<br />

Upward<br />

mobility<br />

21%**<br />

Downward<br />

mobility<br />

n.s.<br />

-13315<br />

63185<br />

Lateral<br />

mobility<br />

17%**<br />

2431 (480 upward transitions; 638 downward<br />

transitions; 1313 lateral transitions)<br />

** = significant on 1%-level; * = significant on 5%-level; n.s. = not significant<br />

Special Collaborative Centre 1 86: Hast German Career Study<br />

employment can prevent one from getting a better Job, but it is not the<br />

start of a downward slope.<br />

What happens after a long single unemployment spell in the next<br />

Job? Individuais stay longer in their next Job. The figures indicate that<br />

people behave in a more risk-averse manner after a spell of long-term<br />

unemployment: lateral (-7%) äs well äs downward mobility transitions<br />

(-5%) are reduced after single long unemployment spells.<br />

What is the effect for your further career by taking a position below<br />

the level of qualification of your certificate? Is it the start of a<br />

downward slope or can people rebalance resources and positions by<br />

moves of counter-mobility? Data suggest the latter: People with a<br />

lower level of position in relation to the level of their certificate are<br />

more likely to make an upward mobility transition (+4%). They are<br />

also less likely to make downward mobility transitions (-3%). Both results<br />

indicate a tendency of successful counter-mobility to rebalance<br />

resources and positions.<br />

Let us now look at structural influences on mobility in the transformation<br />

process. What is the effect of a rise in the general unemployment<br />

level on individual mobility? The data suggest only a weak effect<br />

of the unemployment level on mobility. There is no significant effect<br />

on vertical mobility, only lateral mobility is slightly reduced (-4%).<br />

Modemisation theory suggests a rise of upward mobility by the<br />

enlargement of the tertiary sector. Indeed data support this optimistic<br />

picture. The chance of individual upward mobility rises with more positions<br />

in the tertiary sector (+8.5%) and the risk of downward mobility<br />

is reduced (-6%). A growth of the tertiary sector in Hast Germany is<br />

connected by a better opportunity structure for individual mobility.<br />

Evolutionary Organisation theory argues that formation and closure<br />

of companies influence individual mobility more than the enlargement<br />

or shrinkage of established companies. Our data on the East<br />

German transformation, which in its initial stage was characterised by<br />

high numbers of formation and closure of companies, support these<br />

suggestions. The formation of new companies offers opportunities for<br />

upward mobility (+1%) and lateral mobility (+0.6%), whereas the closure<br />

of companies leads to a rise of downward mobility and lateral mobility.<br />

The results of the event-history analysis on the effect of unemployment<br />

for mobility with respect to exclusion theory is rather clear<br />

cut: Unemployment is a transitory element of mobility paths. Rather<br />

than determining the direction of social mobility, it is a rather neutral<br />

switch preceding mobility in all directions. The only result that would<br />

fit the usual exclusion discourse is that people with a long record of cumulative<br />

unemployment are less likely to make upward mobility transitions.<br />

In the event history analysis, we also find some hints that<br />

individuals may not simply be the victims of unfavourable conditions;<br />

they try to actively cope with their position. So, after long-term unemployment<br />

spells, they try to hold on to their new Job longer than people<br />

without this experience.<br />

Results of an optimal matching analysis<br />

Before we refute exclusion theory with the empirical results of the<br />

event history analysis, let us be cautious and question the method used.<br />

Maybe there are limits to the method used that prevent us from discovering<br />

exclusionary phenomena: The focus of event-history analysis is