European Geologist European Geologist Geoheritage - learning ...

European Geologist European Geologist Geoheritage - learning ...

European Geologist European Geologist Geoheritage - learning ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

an attractive type of ‘displaced’ geoheritage,<br />

allowing the study of facies development<br />

and weathering phenomena in conjunction<br />

with physical characteristics of the building<br />

materials.<br />

Geoconservation as part of the geo-biocultural<br />

heritage management chain<br />

Barriers to conservation of geosites / preservation<br />

of geodiversity<br />

Experience from many countries shows<br />

that geologists as a stand-alone group are<br />

unable or even unwilling to protect geodiversity<br />

or to convey the message of its<br />

urgency. Geomorphologists (physical geographers<br />

in the Belgian context) share the<br />

same values. With their backgrounds in<br />

the educational system or land use agencies<br />

they are more efficient in dealing with<br />

the public. Moreover, sharing knowledge<br />

among geologists, geomorphologists, soil<br />

scientists and hydrologists will bring a<br />

more holistic approach, which is necessary<br />

to convince society as a whole of the<br />

importance of geodiversity.<br />

Filling the gap left by the inadequate<br />

treatment of System Earth in the educational<br />

system, resulting directly in lack of<br />

visibility, indirectly in insufficient numbers<br />

of professionals and funding of geoconservation<br />

programmes, can be achieved by<br />

involving volunteers. Because of their different<br />

background and interest they allow<br />

overlap with conservation of biodiversity<br />

and cultural heritage issues. A problematic<br />

issue is the rapid deterioration or abandonment<br />

of many geosites located in quarries,<br />

once quarrying operations are terminated.<br />

Without local volunteers, remedial<br />

action may come too late or become more<br />

expensive.<br />

Nature conservation groups are well<br />

established in our society and manage those<br />

areas where conservation is most urgently<br />

needed. Cooperation would create a winwin<br />

situation because these groups can provide<br />

the supporting framework for effective<br />

geosite protection while they can use<br />

geoscientific input for sustainable management<br />

of ecosystems. This requires mutual<br />

understanding: biologists should realize<br />

that nature is dynamic and that working<br />

geological processes contribute to ecosystem<br />

resilience, while geologists should<br />

intuitively accept that living nature has a<br />

higher value from an ethical perspective.<br />

There are so many urgent needs for conservation<br />

of the geological heritage and so<br />

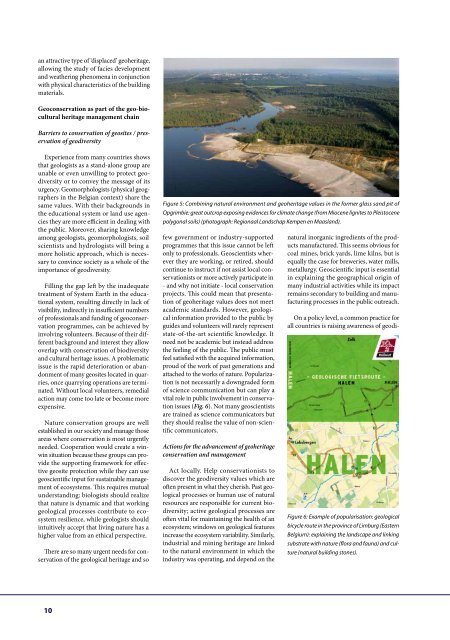

Figure 5: Combining natural environment and geoheritage values in the former glass sand pit of<br />

Opgrimbie: great outcrop exposing evidences for climate change (from Miocene lignites to Pleistocene<br />

polygonal soils) (photograph: Regionaal Landschap Kempen en Maasland).<br />

few government or industry-supported<br />

programmes that this issue cannot be left<br />

only to professionals. Geoscientists wherever<br />

they are working, or retired, should<br />

continue to instruct if not assist local conservationists<br />

or more actively participate in<br />

- and why not initiate - local conservation<br />

projects. This could mean that presentation<br />

of geoheritage values does not meet<br />

academic standards. However, geological<br />

information provided to the public by<br />

guides and volunteers will rarely represent<br />

state-of-the-art scientific knowledge. It<br />

need not be academic but instead address<br />

the feeling of the public. The public must<br />

feel satisfied with the acquired information,<br />

proud of the work of past generations and<br />

attached to the works of nature. Popularization<br />

is not necessarily a downgraded form<br />

of science communication but can play a<br />

vital role in public involvement in conservation<br />

issues (Fig. 6). Not many geoscientists<br />

are trained as science communicators but<br />

they should realise the value of non-scientific<br />

communicators.<br />

Actions for the advancement of geoheritage<br />

conservation and management<br />

Act locally. Help conservationists to<br />

discover the geodiversity values which are<br />

often present in what they cherish. Past geological<br />

processes or human use of natural<br />

resources are responsible for current biodiversity;<br />

active geological processes are<br />

often vital for maintaining the health of an<br />

ecosystem; windows on geological features<br />

increase the ecosystem variability. Similarly,<br />

industrial and mining heritage are linked<br />

to the natural environment in which the<br />

industry was operating, and depend on the<br />

natural inorganic ingredients of the products<br />

manufactured. This seems obvious for<br />

coal mines, brick yards, lime kilns, but is<br />

equally the case for breweries, water mills,<br />

metallurgy. Geoscientific input is essential<br />

in explaining the geographical origin of<br />

many industrial activities while its impact<br />

remains secondary to building and manufacturing<br />

processes in the public outreach.<br />

On a policy level, a common practice for<br />

all countries is raising awareness of geodi-<br />

Figure 6: Example of popularisation: geological<br />

bicycle route in the province of Limburg (Eastern<br />

Belgium): explaining the landscape and linking<br />

substrate with nature (flora and fauna) and culture<br />

(natural building stones).<br />

10