Heat

heat-story

heat-story

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Turn Down the <strong>Heat</strong>: Why a 4°C Warmer World Must Be Avoided<br />

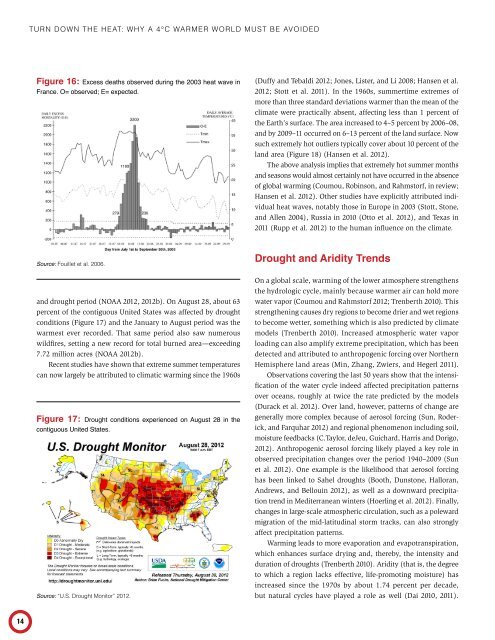

Figure 16: Excess deaths observed during the 2003 heat wave in<br />

France. O= observed; E= expected.<br />

(Duffy and Tebaldi 2012; Jones, Lister, and Li 2008; Hansen et al.<br />

2012; Stott et al. 2011). In the 1960s, summertime extremes of<br />

more than three standard deviations warmer than the mean of the<br />

climate were practically absent, affecting less than 1 percent of<br />

the Earth’s surface. The area increased to 4–5 percent by 2006–08,<br />

and by 2009–11 occurred on 6–13 percent of the land surface. Now<br />

such extremely hot outliers typically cover about 10 percent of the<br />

land area (Figure 18) (Hansen et al. 2012).<br />

The above analysis implies that extremely hot summer months<br />

and seasons would almost certainly not have occurred in the absence<br />

of global warming (Coumou, Robinson, and Rahmstorf, in review;<br />

Hansen et al. 2012). Other studies have explicitly attributed individual<br />

heat waves, notably those in Europe in 2003 (Stott, Stone,<br />

and Allen 2004), Russia in 2010 (Otto et al. 2012), and Texas in<br />

2011 (Rupp et al. 2012) to the human influence on the climate.<br />

Source: Fouillet et al. 2006.<br />

and drought period (NOAA 2012, 2012b). On August 28, about 63<br />

percent of the contiguous United States was affected by drought<br />

conditions (Figure 17) and the January to August period was the<br />

warmest ever recorded. That same period also saw numerous<br />

wildfires, setting a new record for total burned area—exceeding<br />

7.72 million acres (NOAA 2012b).<br />

Recent studies have shown that extreme summer temperatures<br />

can now largely be attributed to climatic warming since the 1960s<br />

Figure 17: Drought conditions experienced on August 28 in the<br />

contiguous United States.<br />

Source: “U.S. Drought Monitor” 2012.<br />

Drought and Aridity Trends<br />

On a global scale, warming of the lower atmosphere strengthens<br />

the hydrologic cycle, mainly because warmer air can hold more<br />

water vapor (Coumou and Rahmstorf 2012; Trenberth 2010). This<br />

strengthening causes dry regions to become drier and wet regions<br />

to become wetter, something which is also predicted by climate<br />

models (Trenberth 2010). Increased atmospheric water vapor<br />

loading can also amplify extreme precipitation, which has been<br />

detected and attributed to anthropogenic forcing over Northern<br />

Hemisphere land areas (Min, Zhang, Zwiers, and Hegerl 2011).<br />

Observations covering the last 50 years show that the intensification<br />

of the water cycle indeed affected precipitation patterns<br />

over oceans, roughly at twice the rate predicted by the models<br />

(Durack et al. 2012). Over land, however, patterns of change are<br />

generally more complex because of aerosol forcing (Sun, Roderick,<br />

and Farquhar 2012) and regional phenomenon including soil,<br />

moisture feedbacks (C.Taylor, deJeu, Guichard, Harris and Dorigo,<br />

2012). Anthropogenic aerosol forcing likely played a key role in<br />

observed precipitation changes over the period 1940–2009 (Sun<br />

et al. 2012). One example is the likelihood that aerosol forcing<br />

has been linked to Sahel droughts (Booth, Dunstone, Halloran,<br />

Andrews, and Bellouin 2012), as well as a downward precipitation<br />

trend in Mediterranean winters (Hoerling et al. 2012). Finally,<br />

changes in large-scale atmospheric circulation, such as a poleward<br />

migration of the mid-latitudinal storm tracks, can also strongly<br />

affect precipitation patterns.<br />

Warming leads to more evaporation and evapotranspiration,<br />

which enhances surface drying and, thereby, the intensity and<br />

duration of droughts (Trenberth 2010). Aridity (that is, the degree<br />

to which a region lacks effective, life-promoting moisture) has<br />

increased since the 1970s by about 1.74 percent per decade,<br />

but natural cycles have played a role as well (Dai 2010, 2011).<br />

14