Heat

heat-story

heat-story

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Turn Down the <strong>Heat</strong>: Why a 4°C Warmer World Must Be Avoided<br />

• United States: In the United State, significant nonlinear effects<br />

are observed above local temperatures of 29°C for maize, 30°C<br />

for soybeans, and 32°C for cotton (Schlenker and Roberts 2009).<br />

• Australia: Large negative effects of a “surprising” dimension<br />

have been found in Australia for regional warming variations<br />

of +2°C, which Asseng, Foster, and Turner argue have general<br />

applicability and could indicate a risk that “could substantially<br />

undermine future global food security” (Asseng, Foster, and<br />

Turner 2011).<br />

• India: Lobell et al. 2012 analyzed satellite measurements<br />

of wheat growth in northern India to estimate the effect of<br />

extreme heat above 34°C. Comparison with commonly used<br />

process-based crop models led them to conclude that crop<br />

models probably underestimate yield losses for warming of<br />

2°C or more by as much as 50 percent for some sowing dates,<br />

where warming of 2°C more refers to an artificial increase of<br />

daily temperatures of 2°C. This effect might be significantly<br />

stronger under higher temperature increases.<br />

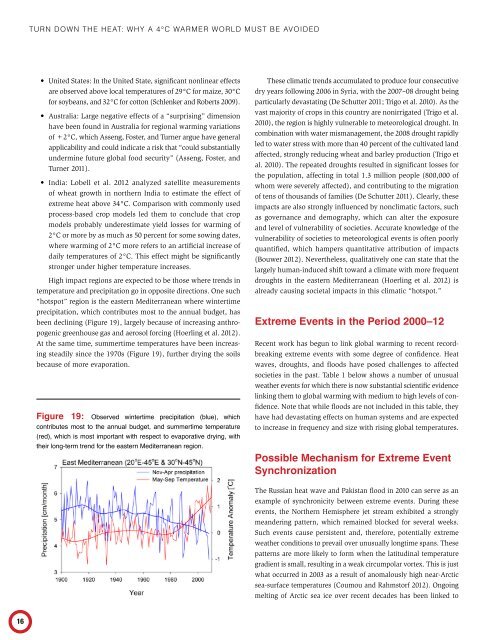

High impact regions are expected to be those where trends in<br />

temperature and precipitation go in opposite directions. One such<br />

“hotspot” region is the eastern Mediterranean where wintertime<br />

precipitation, which contributes most to the annual budget, has<br />

been declining (Figure 19), largely because of increasing anthropogenic<br />

greenhouse gas and aerosol forcing (Hoerling et al. 2012).<br />

At the same time, summertime temperatures have been increasing<br />

steadily since the 1970s (Figure 19), further drying the soils<br />

because of more evaporation.<br />

Figure 19: Observed wintertime precipitation (blue), which<br />

contributes most to the annual budget, and summertime temperature<br />

(red), which is most important with respect to evaporative drying, with<br />

their long-term trend for the eastern Mediterranean region.<br />

These climatic trends accumulated to produce four consecutive<br />

dry years following 2006 in Syria, with the 2007–08 drought being<br />

particularly devastating (De Schutter 2011; Trigo et al. 2010). As the<br />

vast majority of crops in this country are nonirrigated (Trigo et al.<br />

2010), the region is highly vulnerable to meteorological drought. In<br />

combination with water mismanagement, the 2008 drought rapidly<br />

led to water stress with more than 40 percent of the cultivated land<br />

affected, strongly reducing wheat and barley production (Trigo et<br />

al. 2010). The repeated droughts resulted in significant losses for<br />

the population, affecting in total 1.3 million people (800,000 of<br />

whom were severely affected), and contributing to the migration<br />

of tens of thousands of families (De Schutter 2011). Clearly, these<br />

impacts are also strongly influenced by nonclimatic factors, such<br />

as governance and demography, which can alter the exposure<br />

and level of vulnerability of societies. Accurate knowledge of the<br />

vulnerability of societies to meteorological events is often poorly<br />

quantified, which hampers quantitative attribution of impacts<br />

(Bouwer 2012). Nevertheless, qualitatively one can state that the<br />

largely human-induced shift toward a climate with more frequent<br />

droughts in the eastern Mediterranean (Hoerling et al. 2012) is<br />

already causing societal impacts in this climatic “hotspot.”<br />

Extreme Events in the Period 2000–12<br />

Recent work has begun to link global warming to recent recordbreaking<br />

extreme events with some degree of confidence. <strong>Heat</strong><br />

waves, droughts, and floods have posed challenges to affected<br />

societies in the past. Table 1 below shows a number of unusual<br />

weather events for which there is now substantial scientific evidence<br />

linking them to global warming with medium to high levels of confidence.<br />

Note that while floods are not included in this table, they<br />

have had devastating effects on human systems and are expected<br />

to increase in frequency and size with rising global temperatures.<br />

Possible Mechanism for Extreme Event<br />

Synchronization<br />

The Russian heat wave and Pakistan flood in 2010 can serve as an<br />

example of synchronicity between extreme events. During these<br />

events, the Northern Hemisphere jet stream exhibited a strongly<br />

meandering pattern, which remained blocked for several weeks.<br />

Such events cause persistent and, therefore, potentially extreme<br />

weather conditions to prevail over unusually longtime spans. These<br />

patterns are more likely to form when the latitudinal temperature<br />

gradient is small, resulting in a weak circumpolar vortex. This is just<br />

what occurred in 2003 as a result of anomalously high near-Arctic<br />

sea-surface temperatures (Coumou and Rahmstorf 2012). Ongoing<br />

melting of Arctic sea ice over recent decades has been linked to<br />

16