Screening for cancer: are biomarkers of value?

Screening for cancer: are biomarkers of value?

Screening for cancer: are biomarkers of value?

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

– February/March 2011 28 Molecular diagnostics<br />

germline sequencing and insertion/deletion<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> the MMR genes. If the<br />

tumour has been previously analysed by<br />

immunohistochemistry, targeted germline<br />

sequencing and insertion/deletion<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> the gene corresponding to the<br />

missing MMR protein can be per<strong>for</strong>med.<br />

Pre-analytic and analytic<br />

considerations <strong>of</strong> molecular<br />

diagnostic methods<br />

Genetic testing <strong>of</strong> solid tissue specimens<br />

presents a unique challenge <strong>for</strong> the clinical<br />

laboratory. Samples vary widely in tissue<br />

quantity (e.g. fine needle biopsy vs. resection<br />

specimen), quality (e.g. fresh frozen<br />

vs. <strong>for</strong>malin-fixed <strong>for</strong> 72 hours), and heterogeneity<br />

<strong>of</strong> tumour and non-tumour<br />

tissue. Due to these factors, highly robust<br />

and sensitive methods that can detect a<br />

clinically significant variant present in a<br />

low proportion <strong>of</strong> the sample <strong>are</strong> needed.<br />

Traditional Sanger sequencing has a sensitivity<br />

<strong>of</strong> only ~15-20% to detect minor<br />

allele populations within a mixture,<br />

which can result in false negative results<br />

<strong>for</strong> KRAS testing [29]. Pyrosequencing<br />

and melting curve analysis generally have<br />

better sensitivity, at ~1-10% [29]. Newer<br />

methods that increase sensitivity further<br />

to ~0.1-1% include co-amplification at<br />

lower denaturation temperature (COLD)-<br />

PCR, and peptide nucleic acid (PNA)<br />

clamping [30, 31]. Such sensitive methods<br />

have been described in the literature <strong>for</strong><br />

KRAS [30-32] and BRAF [32] mutation<br />

detection in CRC, and have been shown<br />

to improve diagnostic accuracy. Additional<br />

techniques which could allow ultrasensitive<br />

detection <strong>of</strong> somatic mutations<br />

include next-generation sequencing [33]<br />

and limiting-dilution-PCR [34]. Importantly,<br />

with the increased ability to detect<br />

minor mutant populations within the<br />

sample, it will be necessary to determine<br />

the clinically relevant threshold in addition<br />

to the absolute analytical threshold.<br />

Conclusions and<br />

recommendations<br />

Marked improvements in our understanding<br />

<strong>of</strong> CRC biology over the last few years<br />

have led to the discovery <strong>of</strong> several genetic<br />

<strong>biomarkers</strong> that guide treatment and<br />

establish prognosis <strong>of</strong> patients with CRC.<br />

Although many <strong>biomarkers</strong> have been<br />

studied, currently only KRAS, BRAF, and<br />

MSI <strong>are</strong> sufficiently validated to support<br />

routine clinical use. Cases in which MSI is<br />

suspected based on clinicopathologic data<br />

should be tested. If MSI is demonstrated,<br />

the distinction between Lynch syndrome<br />

and sporadic CRC is fundamental to determine<br />

the necessity <strong>of</strong> genetic counselling<br />

and close oncologic surveillance. Sporadic<br />

CRC cases should be evaluated <strong>for</strong> KRAS<br />

and possibly BRAF if anti-EGFR therapy is<br />

an option. In the future, testing the PI3K<br />

pathway genes PIK3CA and PTEN may<br />

help define the population which is most<br />

likely to benefit from the expensive anti-<br />

EGFR treatment. The per<strong>for</strong>mance <strong>of</strong> the<br />

molecular methods used <strong>for</strong> the above<br />

determinations needs to be considered<br />

and clearly communicated so that patients<br />

receive the most accurate and meaningful<br />

in<strong>for</strong>mation, and do not over-interpret the<br />

laboratory data.<br />

As the era <strong>of</strong> molecular oncology and<br />

personalised medicine unfolds, many<br />

changes in the way <strong>cancer</strong> is currently<br />

diagnosed and treated <strong>are</strong> expected to<br />

occur. Laboratory directors and staff alike<br />

have the responsibility <strong>of</strong> keeping up with<br />

the pace <strong>of</strong> change to continue <strong>of</strong>fering<br />

the best diagnostic testing to clinicians<br />

and patients.<br />

References<br />

1. Karsa LV et al. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol<br />

2010; 24(4): 381-396.<br />

2. Boland CR et al. Gastroenterology 2010;<br />

138(6):2073-2087.e2073.<br />

3. Vilar E et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2010; 7(3):153-162.<br />

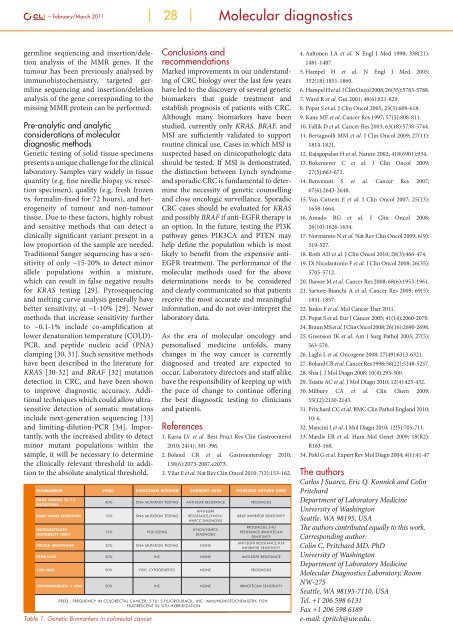

Biomarker Freq. Detection Method Current Uses Possible Future Uses<br />

KRAS codon 12/13<br />

mutations<br />

40% DNA mutation testing Anti-EGFR resistance Prognosis<br />

BRAF V600E mutation 10% DNA mutation testing<br />

Microsatellite<br />

instability (MSI)<br />

15% PCR/sizing<br />

Anti-EGFR<br />

resistance,Lynch/<br />

HNPCC diagnosis<br />

Lynch/HNPCC<br />

diagnosis<br />

PIK3CA mutations 20% DNA mutation testing None<br />

BRAF inhibitor sensitivity<br />

Prognosis,5-FU<br />

resistance,Irinotecan<br />

sensitivity<br />

Anti-EGFR resistance,PI3K<br />

inhibitor sensitivity<br />

PTEN loss 30% IHC None Anti-EGFR resistance<br />

18q loss 50% FISH, cytogenetics None Prognosis<br />

Topoisomerase 1 low 50% IHC None Irinotecan sensitivity<br />

Freq.: Frequency in colorectal <strong>cancer</strong>; 5-FU: 5-fluorouracil; IHC: Immunohistochemistry; FISH:<br />

Fluorescent in situ hybridization<br />

Table 1. Genetic Biomarkers in colorectal <strong>cancer</strong>.<br />

4. Aaltonen LA et al. N Engl J Med 1998; 338(21):<br />

1481-1487.<br />

5. Hampel H et al. N Engl J Med 2005;<br />

352(18):1851-1860.<br />

6. Hampel H et al. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(35):5783-5788.<br />

7. Ward R et al. Gut 2001; 48(6):821-829.<br />

8. Popat S et al. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(3):609-618.<br />

9. Kane MF et al. Cancer Res 1997; 57(5):808-811.<br />

10. Fallik D et al. Cancer Res 2003; 63(18):5738-5744.<br />

11. Bertagnolli MM et al. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27(11):<br />

1814-1821.<br />

12. Rajagopalan H et al. Nature 2002; 418(6901):934.<br />

13. Bokemeyer C et al. J Clin Oncol 2009;<br />

27(5):663-671.<br />

14. Benvenuti S et al. Cancer Res 2007;<br />

67(6):2643-2648.<br />

15. Van Cutsem E et al. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(13):<br />

1658-1664.<br />

16. Amado RG et al. J Clin Oncol 2008;<br />

26(10):1626-1634.<br />

17. Normanno N et al. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2009; 6(9):<br />

519-527.<br />

18. Roth AD et al. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(3):466-474.<br />

19. Di Nicolantonio F et al. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(35):<br />

5705-5712.<br />

20. Jhawer M et al. Cancer Res 2008; 68(6):1953-1961.<br />

21. Sartore-Bianchi A et al. Cancer Res 2009; 69(5):<br />

1851-1857.<br />

22. Janku F et al. Mol Cancer Ther 2011.<br />

23. Popat S et al. Eur J Cancer 2005; 41(14):2060-2070.<br />

24. Braun MS et al. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(16):2690-2698.<br />

25. Greenson JK et al. Am J Surg Pathol 2003; 27(5):<br />

563-570.<br />

26. Laghi L et al. Oncogene 2008; 27(49):6313-6321.<br />

27. Boland CR et al. Cancer Res 1998; 58(22):5248-5257.<br />

28. Shia J. J Mol Diagn 2008; 10(4):293-300.<br />

29. Tsiatis AC et al. J Mol Diagn 2010; 12(4):425-432.<br />

30. Milbury CA et al. Clin Chem 2009;<br />

55(12):2130-2143.<br />

31. Pritchard CC et al. BMC Clin Pathol England 2010;<br />

10: 6.<br />

32. Mancini I et al. J Mol Diagn 2010; 12(5):705-711.<br />

33. Mardis ER et al. Hum Mol Genet 2009; 18(R2):<br />

R163-168.<br />

34. Pohl G et al. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2004; 4(1):41-47<br />

The authors<br />

Carlos J Su<strong>are</strong>z, Eric Q. Konnick and Colin<br />

Pritchard<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Laboratory Medicine<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Washington<br />

Seattle, WA 98195, USA<br />

The authors contributed equally to this work.<br />

Corresponding author:<br />

Colin C. Pritchard MD, PhD<br />

University <strong>of</strong> Washington<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Laboratory Medicine<br />

Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, Room<br />

NW-275<br />

Seattle, WA 98195-7110, USA<br />

Tel. +1 206 598 6131<br />

Fax +1 206 598 6189<br />

e-mail: cpritch@uw.edu.