Office of Naval Research - National Transportation Library

Office of Naval Research - National Transportation Library

Office of Naval Research - National Transportation Library

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

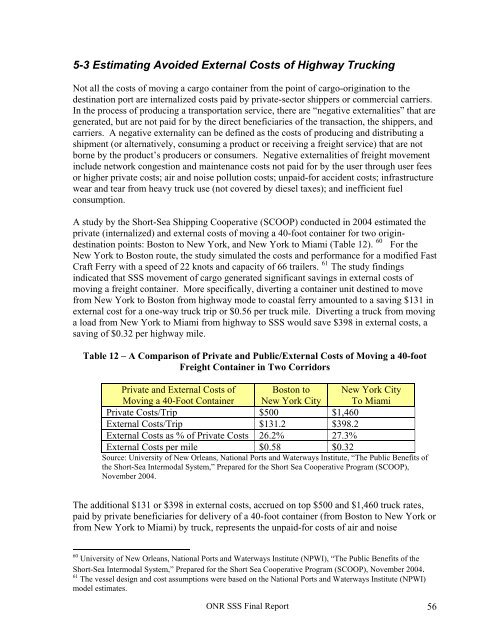

5-3 Estimating Avoided External Costs <strong>of</strong> Highway TruckingNot all the costs <strong>of</strong> moving a cargo container from the point <strong>of</strong> cargo-origination to thedestination port are internalized costs paid by private-sector shippers or commercial carriers.In the process <strong>of</strong> producing a transportation service, there are “negative externalities” that aregenerated, but are not paid for by the direct beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> the transaction, the shippers, andcarriers. A negative externality can be defined as the costs <strong>of</strong> producing and distributing ashipment (or alternatively, consuming a product or receiving a freight service) that are notborne by the product’s producers or consumers. Negative externalities <strong>of</strong> freight movementinclude network congestion and maintenance costs not paid for by the user through user feesor higher private costs; air and noise pollution costs; unpaid-for accident costs; infrastructurewear and tear from heavy truck use (not covered by diesel taxes); and inefficient fuelconsumption.A study by the Short-Sea Shipping Cooperative (SCOOP) conducted in 2004 estimated theprivate (internalized) and external costs <strong>of</strong> moving a 40-foot container for two origindestinationpoints: Boston to New York, and New York to Miami (Table 12). 60 For theNew York to Boston route, the study simulated the costs and performance for a modified FastCraft Ferry with a speed <strong>of</strong> 22 knots and capacity <strong>of</strong> 66 trailers. 61 The study findingsindicated that SSS movement <strong>of</strong> cargo generated significant savings in external costs <strong>of</strong>moving a freight container. More specifically, diverting a container unit destined to movefrom New York to Boston from highway mode to coastal ferry amounted to a saving $131 inexternal cost for a one-way truck trip or $0.56 per truck mile. Diverting a truck from movinga load from New York to Miami from highway to SSS would save $398 in external costs, asaving <strong>of</strong> $0.32 per highway mile.Table 12 – A Comparison <strong>of</strong> Private and Public/External Costs <strong>of</strong> Moving a 40-footFreight Container in Two CorridorsPrivate and External Costs <strong>of</strong>Moving a 40-Foot ContainerBoston toNew York CityNew York CityTo MiamiPrivate Costs/Trip $500 $1,460External Costs/Trip $131.2 $398.2External Costs as % <strong>of</strong> Private Costs 26.2% 27.3%External Costs per mile $0.58 $0.32Source: University <strong>of</strong> New Orleans, <strong>National</strong> Ports and Waterways Institute, “The Public Benefits <strong>of</strong>the Short-Sea Intermodal System,” Prepared for the Short Sea Cooperative Program (SCOOP),November 2004.The additional $131 or $398 in external costs, accrued on top $500 and $1,460 truck rates,paid by private beneficiaries for delivery <strong>of</strong> a 40-foot container (from Boston to New York orfrom New York to Miami) by truck, represents the unpaid-for costs <strong>of</strong> air and noise60 University <strong>of</strong> New Orleans, <strong>National</strong> Ports and Waterways Institute (NPWI), “The Public Benefits <strong>of</strong> theShort-Sea Intermodal System,” Prepared for the Short Sea Cooperative Program (SCOOP), November 2004.61 The vessel design and cost assumptions were based on the <strong>National</strong> Ports and Waterways Institute (NPWI)model estimates.ONR SSS Final Report 56