ISSUE 136 : May/Jun - 1999 - Australian Defence Force Journal

ISSUE 136 : May/Jun - 1999 - Australian Defence Force Journal

ISSUE 136 : May/Jun - 1999 - Australian Defence Force Journal

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

NO. <strong>136</strong>MAY/JUNE<strong>1999</strong>

<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>Board of ManagementBrigadier A.S. D’Hagé, AM, MC (Chairman)Captain J.P.D. Hodgman, RANLieutenant Colonel N.F. JamesGroup Captain C.A. BeattyMs K. GriffithThe fact that an advertisement is accepted forpublication in the <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong><strong>Journal</strong> does not imply that the product or servicehas the endorsement of the <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong><strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>, the <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> or theDepartment of <strong>Defence</strong>. Readers are advised toseek professional advice where appropriate as the<strong>Journal</strong> can accept no responsibility for the claimsof its advertisers.Contributions of any length will be considered but,as a guide, 3000 words is the ideal length. Articlesshould be typed double spaced, on one side of thepaper, or preferably submitted on disk in a wordprocessing format. Hardcopy should be suppliedin duplicate.All contributions and correspondence should beaddressed to:The Managing Editor<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>Building B-4-26Russell OfficesCANBERRA ACT 2600(02) 6265 2682 or 6265 2999Fax (02) 6265 6972CopyrightThe material contained in the <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong><strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> is the copyright of the Department of<strong>Defence</strong>. No part of the publication may bereproduced, stored in a retrieval system, ortransmitted in any form or by any means, electronic,mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwisewithout the consent of the Managing Editor.Advertising Enquiries:(02) 9876 5333, (02) 6265 1193General Enquiries:(02) 6265 3234Email: adfj@spirit.com.auwww.adfa.oz.au/dod/dfj/© Commonwealth of Australia <strong>1999</strong>ISSN 1320-2545Published by the Department of <strong>Defence</strong>Canberra <strong>1999</strong>

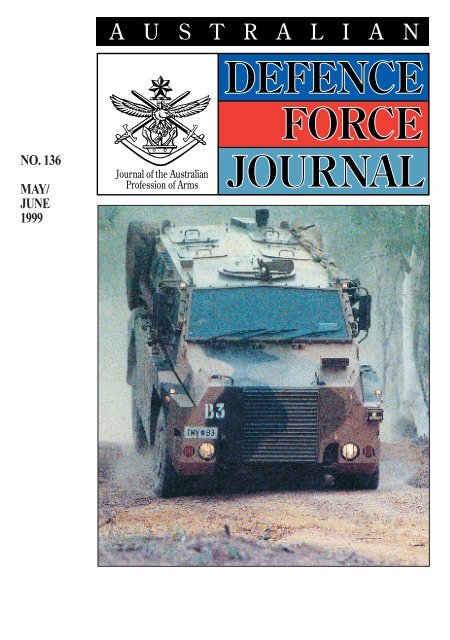

No. <strong>136</strong> <strong>May</strong>/<strong>Jun</strong>e <strong>1999</strong>Front CoverThe <strong>Australian</strong> Army Bushranger vehicle atMajura Range near Canberra.3. Letters to the EditorContents5. What Has Gone WrongCaptain M.A.J. Watson, RAA13. Strategy and CrisisBrigadier J.J.A. Wallace, AM23. Peace DevelopmentDan Baschiera, <strong>Defence</strong> Community Organisation35. Comparing <strong>Australian</strong> and New Zealand <strong>Defence</strong> andForeign PolicyFlight Lieutenant S.A. Madsen, RAAF41. The Importance of Training Needs Analysis inIntegrated Logistic SupportLieutenant Commander Jim Kenny, RAN43. Unconventional Warfare – An OverviewMajor R.C. Moor, Ra Inf.51. Book ReviewsPhotograph bySergeant Dave BroosManaging EditorMichael P. TraceyEditorIrene M. CoombesPrinted in Australia by National CapitalPrinting, Fyshwick, ACT 2609Contributors are urged to ensure the accuracy of the informationcontained in their articles; the Board of Management accepts noresponsibility for errors of fact.Permission to reprint articles in the <strong>Journal</strong> will generally be readilygiven by the Managing Editor after consultation with the author. Anyreproduced articles should bear an acknowledgement of source.The views expressed in the articles are the author’s own and shouldnot be construed as official opinion or policy.

REACHING THETOP WITH YOURMESSAGE?The advantages of advertising in the<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> are far reaching.Editorial EnquiriesPhone: +61 2 6265 1193Fax: +61 2 6265 6972E-mail: adfj@spirit.com.auInternet: www.adfa.oz.au/dod/dfj/Advertising EnquiriesPhone: +61 2 6290 1767or +61 2 6239 2287E-mail: ey.bis@actonline.com.au

3Letters to the EditorAirborne <strong>Force</strong>sDear Editor,Major Basan provided a cogent analysis on arelevant topic in his article “Airborne <strong>Force</strong>s: TheTwenty-First Century’s Rapid Dominance Solution”,(ADFJ Nov/Dec 1998).His thesis is well supported by contemporary trendsin warfare and the emerging strategic environment.Importantly, airborne operations have the potential to bedecisive for either strategic or tactical objectives.Furthermore, with imaginative planning and appropriatecapability sets, airborne forces are employable acrossthe spectrum of conventional to irregular warfare.A key force development issue arises if we acceptthe tenets of Major Basan’s article. Could thedevelopment of Australia’s airborne forces significantlyenhance our military options in the context of amaritime strategy? Airborne characteristics such asstrategic mobility, strike power and versatility should becarefully considered.However, airborne forces alone are not the solution.Ultimately, an effective maritime strategy will rely onbalanced capabilities to project air, naval and landpower. Perhaps further developing our airbornecapability is an opportunity to improve the balance.Certainly, responsive and lethal airborne forces wouldadd to the operational options for Australia’s emergingmaritime strategy.P.K. SinghLieutenant ColonelThe Knowledge EdgeDear Editor,I have just finished reading “The Relevance of theKnowledge Edge” by Professor Paul Dibb in theJan/Feb <strong>1999</strong> ADFJ and felt utterly depressed by thenegative attitude of the Canberra crowd who have suchinfluence on the decision making process in relation to<strong>Defence</strong> Policy. The article is littered with quotes suchas “Every <strong>Australian</strong> defence planner needs toremember that there are limits to Australia’s defencecapability”, “the realities of limited resources and thesmall size of the ADF will discipline those who dreamabout aircraft carriers and expeditionary forces for highlevel conflicts”, “For Australia, as a middle power withlimited defence capacity”, “this kind of adaptiveness inAustralia’s force planning will be far from easy giventhe limited financial resources that are likely to beavailable”.Isn’t it about time we took a more positive view ofdefence and decided that if Australia is worth defendingthen its about time Federal Governments made theresources available to do the job properly. What weneed is a large dose of the American “can do” attitudeinstead of the dreadful “can’t do” mentality thatpervades so much of <strong>Australian</strong> life.The fact is that the ADF’s present force structurewouldn’t, as Sir James Killen noted about twenty fiveyears ago, be capable of defending Bondi beach on aSunday afternoon. And yet we are fed a constant load ofrubbish by Government, Bureaucracy, and ServiceChiefs about our self reliance. Self reliance for what?If it had the will, Australia could and should becomea genuine middle ranking power that had a realinfluence on events in our region to an extent that hasnot been visible since World War 2.Our Foreign Affairs Department gives theimpression of being a toothless tiger staffed by peopleincapable of assessing events in our region and advisinga succession of Prime Ministers and Foreign Ministersswanning around the world gladhanding theircounterparts and achieving little.Bougainville is the classic example of a seriousdispute for which we had a prime responsibility, but didnothing for nine years until New Zealand took up thecudgells to try and broker a solution. Already the PrimeMinister and Foreign Minister are hedging their bets inrelation to Timor with Mr Downer making theunfortunate and stupid comment about not wanting<strong>Australian</strong>s coming back in body bags.Perhaps someone ought to tell someone in Canberrathat the armed forces do occasionally suffer casualtieswhen on operational duties. We can only be pleased thatno one these days has to make the kind of decisions thathad to be made during the two world wars.Paul Dibb observes “What will have to be avoided,however is any temptation for politicians to reach downinto military operational decisions”. God forbid thatever happening, but it could occur if our military leadersdon’t show more determination in protecting theintegrity of the ADF than they have in the recent past.There needs to be a serious commitment by FederalGovernments to provide the resources for the ADF totake an effective role in whatever troubles may occur inthe future, because its present structure to either defendAustralia against a hostile threat, which is unlikely in theforeseeable future, or participate in meaningful supportin regional trouble spots is totally inadequate.Peter Firkins

AUSTRALIAN PRISONERS OF WAR<strong>Australian</strong> Prisoners of War spans the Boer War to the Korea War and commemoratesthose <strong>Australian</strong>s who suffered as Prisoners of War in all conflicts.This is the 10th in a series of commemorative books produced by the<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>.This series of publications was produced with the encouragement of the Chief of the<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> and the Secretary of the Department of <strong>Defence</strong> inacknowledgement of the contribution made by former members of the<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> in times of adversity.<strong>Australian</strong> Prisoners of War is available from the office of the<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> at a cost of $29.95.<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> – Mail Order FormAUSTRALIAN PRISONERS OF WARPlease send order to <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>,B-4-26, Russell Offices, CANBERRA ACT 2600Name: ____________________________________________________________________________________Address: __________________________________________________________________________________I enclose a cheque or money order payable to the Receiver of Public Monies for $_________________being payment forcopies of <strong>Australian</strong> Prisoners of War.

What Has Gone WrongBy Captain M.A.J. Watson, RAAAuthor’s NoteThis article is addressed to the senior officers of today. The Army and indeed the <strong>Defence</strong><strong>Force</strong> that you intend to bequeath your subordinates and on a wider scale the Nation will not beworth the paper it is written on.The previous statement is deliberately inflammatory, I make no apologies for that. Itexpresses the view of a single disgruntled malcontent, who is to boot just a mere Captain. Ordoes it? Disaffection within the junior officer ranks is widespread. Whether you choose toacknowledge that fact is irrelevant. The perception that the Army lacks direction and purpose isreality for many junior officers. Alarmingly, recent graduates from the Royal Military Collegeexpressed the view that the only worthwhile Corps for aspiring graduates was RASIGS - for thepotential it offered for civilian employment upon completion of their ROSO! The relative meritsof this statement and the commendable insight of those who arrived at its deduction are outsidethe scope of this work, it does however, offer a telling insight into the psyche of the modernjunior officer.Initially I intend to outline what is wrong with the Army from my perspective. Your criticismof my presumptuousness is predictable. How could I, with my dearth of experience and narrowglobal perspectives, with any hope of credibility, denigrate what is in effect your life’s work? Ifyour minds remain closed I can’t. I would however remind you that at the end of 1998 the ARAwas short 240 Captains on its post DRP strength. I wager that this represents an increasingproportion of “wheat” to “chaff”. Separation at this stage of one’s working life implies thereasonable prospect of advantageous alternative employment. There is no reason to believe thatthis trend will be reversed, and thus, by default my opening statement will come to fruition.Your next logical objection to my train of argument will be to imply that it is so typical forthose of my “generation” to undermine establishment without feeling the need to propose a viablealternative. I intend to propose a vision for the future, not in this article, but in future works. It isanticipated that you will find my solutions simplistic and puerile, perhaps they are, but that maybe because objectivity is not so problematic when self interest is removed from the equation.Finally, you will employ your ultimate leveller. The assertion that if I no longer care for a lifeof servitude that I should resign my Commission and seek an existence elsewhere. I wouldremind you of the numbers that have chosen to do just that. The truth is that I still care enough tovoice my concerns, fully cognisant of the fact that the vast majority of the Army community willhave no inclination to read this document and those that do are likely to find something within itthat will cause offence.I beseech you to read the opening quotation of my article. I believe it is a fine watershed forreaders of this article. Some readers will lament on how much truth the passage contains whilstothers may feel a twinge of discomfort. To the latter I commend the words of Oliver Cromwell inhis address to the Rump Parliament, “You have sat too long here for any good you have beendoing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go!”

6AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE JOURNAL NO. <strong>136</strong> MAY/JUNE <strong>1999</strong>“Unwatched, a peacetime military willdegenerate into a bureaucracy designed byMegalomaniacs to be a vehicle to satisfy theirego’s. Tactical prowess will be allowed to besubordinate to bureaucratic manoeuvre,leadership will become an intangible used toconceal a lack of depth, and loyalty will be usedas censorship to enable the unfettered impositionof careerist initiatives”Major Pat Stogran, PPCLI, 15 Jul 97IntroductionThe personal circumstances of Major Stogran areirrelevant, as is the fact that the intended target ofhis insightfullness was the Armed <strong>Force</strong>s of is ownnation. The above passage, however, is entirelyappropriate for the current circumstances that prevailacross the Army. At junior officer level there is apalpable sense that the Army has shrugged off anysemblance of its perceived corps values and hasindeed lost its way. The result of this is the belief thatthe Army has begun an inexorable slide intoirrelevance. It was widely lampooned in the Author’sprevious unit that the Army was akin to an old car, onblocks, slowly rusting away in a paddock, a depictionof which is included as Figure 1.As stated in the Author’s Note, this articlerepresents one junior officer’s perception on theprevailing attitude of his fellows. If the readerfundamentally disagrees with the above perception,the validity of this objection being questionable atbest if the reader is not currently a junior officer, thenthis article will have no bearing. This reader shouldproceed no further, rather, they should ensconce theirself in the belief that their ongoing toil is valuable andvalued, unconcerned by the reality that they are thereason for the inclusion of “inexorable” in the aboveparagraph. If this reader gets the impression that theauthor is laughing at them, they are entirely correct.This article will expose the Army’s increasinglydilapidated appearance from the perspective of ajunior officer. Three primary indicators will be usedto attest to the Army’s waning fortunes. Firstly,Army’s share of the <strong>Defence</strong> Budget, secondly,personnel issues and finally, Army’s muddled“vision” for the future. All three issues areintrinsically linked and their cumulative effects arespeeding the Army towards oblivion.Money Is The Root Of All EvilNowhere is the decline of the Army more obviousthan in the percentage of the annual <strong>Defence</strong> Budgetthat it manages to secure for itself, particularly in thearea of Capital Equipment Procurement. Armyapologists will attempt to sight the unsympathetic<strong>Defence</strong> Policies of successive Governments forhaving the effect of syphoning funds into projects forthe Navy and Airforce in order to allow them to denythe air-sea gap. It will be the contention of this article,however, that outside of a vague notion of providingfor Australia’s defence, Australia’s electedofficialdom have neither the capability nor theinclination to actually dictate what the 10 plus billiondollars allocated to the <strong>Defence</strong> Budget are actuallyspent on. 1 If the role played by politicians inspending the <strong>Defence</strong> dollar is minimal then surelythe relative success of the Navy and Airforce is due inno small part to both the quality of their personnel andtheir ability to quantify and articulate a vision for thefuture.Figure 1“Total defence spending for the coming financialyear has been set at $10 945.5m, up $589.2m fromoutlays in the current financial year.” 2 The previousstatement is obviously in relation to FY 98/99. TheArmy Program Actual Outcome for 1997-98 was $1268.3m, 3 in comparison with Navy $721.3m 4 andAirforce $695.0m. 5 Not surprisingly this reflects thehigher total numbers in Army, Service PersonnelRunning Costs alone accounted for $1 098.4m. 6 As a

8AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE JOURNAL NO. <strong>136</strong> MAY/JUNE <strong>1999</strong><strong>Defence</strong> and <strong>Defence</strong> Policy at Government level.Examine the following, “With the 20-20 vision ofhindsight, a former Labor Cabinet minister admits:‘We never did properly scrutinise <strong>Defence</strong>. Therewas nobody in bloody cabinet apart from Kim whounderstood it. (sic) And he could always talk the restof us under the table.’” 23 <strong>Defence</strong>’s worthy politicalmasters know what they want, “Government wantsoptions”, 24 a balanced amorphous mass, capable ofresponding to whatever contingency Governmentwishes to commit to. This is not an unreasonablerequest for close to $11b a year. The excuse thatArmy is missing out on its share of the AcquisitionsBudget due to an unfavourable external environmentis preposterous in the extreme. Army is missing outbecause no one has the nous to dispel a lie.Would The Last One To Leave PleaseTurn Out The LightsThe Mission of the Directorate General CareerManagement-Army (DGCM-A) is, “To maximise<strong>Defence</strong> capabilities by managing Army’s personnelasset in accordance with agreed priorities (sic)ensuring that ‘the right person is in the right job at theright time’” 25 . It would be too easy to launch into avenomous diatribe at the above statement, which intruth would be unwarranted. DGCM-A’sresponsibilities, like those of the Directorate GeneralPersonnel Plans (DGPP) are the metaphoricalequivalent of a large bag filled with two-inch lengthsof string. Their job is a thankless one, analogous to asmall boy suspended from a dyke with all his fingersand toes jammed into an ever-increasing number ofholes. Whilst Army failed to stop the blue and whitesuites from making off with the cookie jar, in terms ofCEPs, this isn’t what is killing the Army, the Army isbleeding to death.It sounds dramatic and there are undoubtablysome that would dismiss the statement as overlyemotive, however the gravity of the situation will beoutlined in the following statistics. It is widely jokedthat all the rats haven’t deserted the sinking ship asyet, they are too busy studying for postgraduatequalifications. The following discussion will centreon Officer separations in the ranks of Captain toLieutenant Colonel. The principal source of data wasthe Deputy Directorate Workforce Planning-Army(DDWP-A) Data Analysis meeting of 17 Feb 99.There has been a 400 per cent increase in the ARAOfficer monthly rolling separation rate in FY 98/99.ARA wide the separation rate as at the end of Januarywas 11.92 per cent, the forecast separation rate for FY98/99 was 10.5 per cent. The total liability in theafore mentioned ranks as at the beginning of Januarywas Captain 6.81 per cent, Major 14.17 per cent andLieutenant Colonel 19.8 per cent. 26 Whilst theLieutenant Colonel figure is alarming it is noted withmalicious and barely concealed glee that it is in theCaptain rank that the first crisis will occur. In theAuthor’s Note a shortfall of 240 Captains wasoutlined, it would seem that in the time of writing thisfigure has climbed to 308 with no sign of abatement,the upshot of this is the recognition that there won’tbe enough Lieutenants in two years eligible forpromotion to fill Captain positions. The suggestedresponse to this dilemma is interesting, to holdCaptains in rank for at least another year, thepredictable course of action for those who are notpromoted is only likely to exacerbate the situation.The Army should look no further when allottingblame for this debacle than the culture that it hasmanaged to inculcate in its members. The author,when assembling this article approached bothDOCM-A and DDWP-A in writing for data on thenumber of Captains in the last two years who haddischarged after undertaking partial or complete postgraduate study. By act or omission the informationwas not forthcoming. The basic proposition here isthat the stated requirement for Officers to obtaintertiary qualifications and the ease with whichsupport, in the form of DFASS and such schemes, forpost graduate study can be accessed when combinedwith a favourable external employment situation ispaving the way for Army’s brightest, if not best, toleave. This is indeed what they are doing. In thecurrent environment there is little or no incentive forjunior officers to pursue professional knowledge. Theeffect of neglecting professional study is exacerbatedwhen it is combined with carte blanche access tomechanisms geared to increasing the prospect ofgaining lucrative employment outside the service.The net effect is that it shouldn’t come as a surprisethat junior officers can converse with more lucidity onthe latest rates for an MBA than the AdvancedWarfighting Experiment.The statistics of people exiting the Army is onlyone portion of the quotient. It is necessary to considerthose opting to join as well. From an Officerperspective, the figures don’t look too bad. This year150 Officer Cadets were inducted for ADFA from atarget of 155 and 130 Staff Cadets were inducted forRMC from a target of 142. This does however haveto be tempered against consideration of thosecandidates that were selected to those that enlisted.For ADFA, non scholarship candidates yielded 98

WHAT HAS GONE WRONG 9enlistees from 122 selected (or 80 per cent) andscholarship candidates yielded 52 enlistees from 100selected (or 52 per cent). In essence, Officerpositions will be offered until the target has beenreached, hence the passable figures. GeneralEnlistment (GE) figures have been included becausethey provide a more level perspective on recruitingtrends. As at the end of February the year to datetarget for Full Time (FT) GE was 879 of which 771(or 87.71 per cent) had been enlisted. It is essential toconsider the Part Time (PT) GE figures as well, forthey are intrinsically linked to Army’s vision for thefuture, their year to date target is 2416 (from a total of3790) of which 1493 (or 61.80 per cent) have beenenlisted. 27 These statistics are crushing the PT Army.Cadre Staff, many of whom are FT junior officers,can relate a litany of PT Army stories that centre onthe common themes of wavering morale, transientcommitment and a genuine questioning of the worthof the PT Army concept. There are even rumblingsamongst the staff at Headquarters 2nd Division as tothe convenient coincidence of the general runningdown of the PT Army and the introduction of phasedcareers for FT personnel.Personnel issues are a paradigmatic enigma in asmuch as Army, having created the problem in the firstplace now has no idea of how to solve it. It was withamusement that the author learnt that “What Colour isyour Parachute?”, a guide for job seekers, was one ofthe widest read, non compulsory texts for thegraduates of Command and Staff College last year.This attitude is endemic, not that this should come asa surprise, if a portion of Officers from the highestechelons down are unashamedly pushing their ownbarrow, middle and junior ranking officers would befools not to follow suit. Superimposed over this is theimplicit message that dissent will not be tolerated.The resultant duplicity, exemplified by those whooutwardly exude a veneer of conscientiousness whilstharbouring their own agendas, is, like most of thecause and effect issues discussed in this article,entirely predictable. Read the opening quotationagain. This situation isn’t likely to change and theresultant exodus of people isn’t likely to decline untilArmy gives its personnel something tangible tobelieve in.We’re On A Road To Nowhere“We are simply kidding ourselves if we think weare not doing a bit of catch-up here. There aresome technologies already fielded by other armieswhich we should have had a long time ago – thearmy has simply fallen behind from atechnological point of view compared to the navyand air force.”Brigadier J.J. Wallace, AMSurely the above passage is the understatement ofthe millennium. As the then Commander of Task<strong>Force</strong> 21 (TF21), Brigadier Wallace’s delicateposition is entirely understood, as is his measuredresponse. For reasons outlined at the end of the lastsection it would have been ultimately futile for him tohave nonchalantly uttered words to the effect of:“We really need to have a good look at ourselves.In the neglectful years since our Army’s fineperformance in the Vietnam War we have allowedourselves to deteriorate, both physically in termsof equipment and intellectually in terms of theoperational art to the point where the notion ofinteroperability exists only in the most vividimagination.”Yes the Army is pursuing new equipment, “thearmy has embarked on its own program ofmodernisation instituting projects like Ninox,Wundarra and Bushranger to take it into the nextcentury”. 28 Well thank you very much, these shouldbe the tools of today’s Army (and sadly in many casesyesterdays), they are likely to be worse than useless inthe time of the empty battlefield, information warfareand autonomous “brilliant” Battlefield OperatingSystems. Equipment is only one, very obviousportion of the metaphorical iceberg that Armycollided with long ago.The Army needs to undergo a cathartic process,for different reasons, but similar to that of the USArmy post its Vietnam War experience. General FredFranks (Retired) and Tom Clancy describe such aprocess in painful detail in their collaborative work,Into the Storm. There is extreme danger in attemptingto find a way ahead that is constructed on a series ofpiecemeal solutions (A21, RTA, TF21) which areunderpinned by false premises and unrealisticassumptions. If the One Army concept is thefoundation of RTA, with its focal areas for Brigadesized Task <strong>Force</strong>s (TF) (including PT Brigades whosemanning figures as illustrated would make even themost optimistic observer cringe) then an obviousdisparity exists with the entire TF Trial process.Whilst TF Trials proceed on their merry, resourcehungry way, there are very disturbing rumourscirculating about the continued viability from amanning perspective of 7 TF in the near future.

10AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE JOURNAL NO. <strong>136</strong> MAY/JUNE <strong>1999</strong>Consider the process outlined below:Define thePresentEngenderRequiredChangeVisualisetheFutureIf it is accepted that this diagram represents aprocess for achieving the grandiose notion of “TheRoad to the Future through ContinuousImprovement” 29 then it is worth examining howArmy’s vision for the future stacks up against it. If itwas the intention of the architects of Army’s future tocreate a force who’s fundamental capabilities lie in itsability to populate the North of Australia, defend keyinstallations (usually the property of the other twoservices and housing their shiny new toys) or chase adisproportionately small enemy around the sunnyNorth whilst expending enormous amounts ofresources (seemingly the thing that the enemy wantedto achieve in the first place) then they should be giventop marks. Army should cease and desist with thischarade forthwith.Strategic Review 97 looks at this early stage like itmay provide some hope of tangible change in the nearfuture. Recent media reports sight the increasedlikelihood of United Nations sponsored Operationsthat would undoubtably be joint in nature but with arequirement for a sizeable and sustainable Armycomponent. 30 There are inherent dangers in thispossible change, on both the conceptual and physicalplanes. Conceptually, whilst this shift in policy hasthe potential to improve Army’s fortunes, it meansthat Army is still subject to the vagaries of changingpolicies, whether they be waxing or waning, Armyhas little or no control of its destiny. Physically, theneglect of Army’s procurement needs outlined in thefirst portion of this article means that there is anecessity for Army to rely overwhelmingly on thequality of its soldiers, particularly at the JNCO level. 31It is commendable that this situation has workedflawlessly to date. Without wishing to suggest anysolutions, the relationship of Training and DoctrineCommand (TRADOC) to the Joint Chiefs PlanningCommittee (JCPC) and the process by which theyconvince the US Government to endorse their visionfor the future could have some relevance to thisissue. 32 As with much of the processes and doctrinethat Australia has borrowed from overseas, all thecomponents are there, they just don’t produce thesame product.ConclusionThis article represents one persons thoughts on thestate of the Army. Whether the reader agrees or not isof little consequence to the author. The purpose ofembarking on this process was neither to engenderchange nor stimulate debate, it was purely anintellectual exercise aimed at recording the author’sthoughts on a particular topic.The threat board is well and truly illuminated.Army’s equipment is, generally, aged well beyond amature state and Army isn’t securing enough moneyfrom the Acquisition budget to replace it. Not enoughpeople are intersted in joining and far too manypeople are leaving. If Army’s life depended on it, andin many ways it does, it can’t tell its members oranyone else for that matter, including the successivegovernments that fund it, what it will look like in tenyears. As outlined, contrary views are neitherwelcomed nor dismissed, if the figures containedwithin are accepted though, it would be interesting tosee what such an argument is based on.There are no rosy outcomes on the horizon, nopanaceas that will ease Army’s collective woes anddefinitely no quick fix, compartmentalised solutionsthat will have any real effect. What is required isdedicated visionaries with the intelligence and driveto make a difference, blessedly they are few and farbetween.NOTES1. Department of <strong>Defence</strong> 1998, <strong>Defence</strong> Annual Report 1997-1998, DPS, Canberra, p. 146.2. La Franchi, P. 1998, ‘Budget 98: F/A-18 Upgrade Sole-Sourced to Boeing’, <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> Business Review, vol17, no 7, 15 <strong>May</strong>, p. 5.3. Department of <strong>Defence</strong> 1998, op. cit., p. 207.4. ibid., p. 198.5. ibid., p. 216.6. ibid., p. 207.7. ibid., p. 152.8. ibid., p. 153.9. ibid., p. 154.10. ibid., p. 249.11. loc. cit.12. ibid., p. 250.13. ibid., pp. 250-251.14. Franchi, op. cit., loc. cit.15. loc. cit.16. loc. cit.17. Cotteril, D. <strong>1999</strong>, ‘Air 87 Contenders Jockey for Position’,<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> Magazine, vol 7, no 2, February <strong>1999</strong>, p. 56.18. Bostock, I, 1998, ‘Habitability the key in Bushranger trials’,Asia-Pacific <strong>Defence</strong> Reporter, October-November 1998, p. 29.19. Ferguson, G. <strong>1999</strong>, ‘Squaring up to the Millennium’s firstChallenge’, op. cit., p. 20.

WHAT HAS GONE WRONG 1120. Franchi, op. cit., loc. cit.21. Snow, D. <strong>1999</strong>, ‘Choose Your Weapons’, The Sydney MorningHerald, 16 Jan, p. 53.22. ibid., p. 52.23. loc. cit.24. Address by MAJGEN P.J. Dunn, AM, Head <strong>Defence</strong>Personnel Executive (HDPE), to the DPE New StartersInduction Day, 22 February <strong>1999</strong>.25. Directorate General Career Management-Army (DGCM-A)presentation to the DPE New Starters Induction Day, 22February <strong>1999</strong>.26. Directorate Officer Career Management-Army (DOCM-A)presentation to the Deputy Directorate Workforce Planning-Army (DDWP-A) Data Analysis Meeting, 17 February 99.27. The Officer Enlistment (OE) and General Enlistment (GE) cellsof the Operations Section at <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> RecruitingOrganisation (DFRO) compiles and maintain all manner ofstatistics on recruiting. This data is accurate for early March<strong>1999</strong>.28. Logue, J. CPL, 1998, ‘Phoenix 98 Future Snapshot’, ArmyMagazine, no 37, December, p. 10.29. 1997 Intermediate Staff Course, Command Leadership andManagement Handbook, <strong>May</strong>, p. 2-9.30. Interview with the Hon John Moore, MP, Minister for <strong>Defence</strong>,ABC 7.30 Report, 11 March <strong>1999</strong>.31. Address by COL Pat McIntosh, AM, Commandant, LandWarfare Centre-Canungra to the 2/97 Intermediate Staff Courseon his experiences as Commanding Officer, <strong>Australian</strong> MedicalSupport <strong>Force</strong>, Rwanda.32. http://www-tradoc.army.mil/tradsmin.htm.Captain Mark Watson graduated from Royal Military College, Duntroon in December 1992 and was allocated to the RAA. He has servedas a Section Commander, an Intelligence Officer, a Gun Position Officer and a Forward Observer with 103 Medium Battery, 8th/12thMedium Regiment. In January 1998 he became a Visits Officer with the Directorate of Protocol and Visits. He is currently OperationsOfficer, General Enlistment, <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> Recruiting Organisation.ROYAL AUSTRALIAN NAVY – MARITIME STUDIES PROGRAMKing-Hall Naval History Conference“History, Strategy and the Rise of <strong>Australian</strong> Naval Power”IntroductionThe first “King-Hall Naval Conference” will be held in Canberra 22-24 July <strong>1999</strong> in the Telstra Theatre at the<strong>Australian</strong> War Memorial, Canberra. It has the theme “History, Strategy and the rise of <strong>Australian</strong> Naval Power” andaims to examine maritime strategic issues at the turn of the century with particular reference to events leading to thecreation of an independent <strong>Australian</strong> Navy.The conference is being jointly sponsored by the Royal <strong>Australian</strong> Navy’s Maritime Studies Program and theSchool of History at the University College, <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> Academy.ProgramConference speakers include a wide range of experts from Australia and overseas, and include:Professor Colin Gray – Sea Power in Modern Strategy.Professor Jon Sumida – Clausewitz, Jomini, Mahan, and Corbett:Misunderstanding and Misuse of Canonical Strategic Texts.Professor John McCarthy – The creation of <strong>Australian</strong> Naval Strategy.Dr John Reeve – The Rise of Modern Naval Strategy.Dr Nicholas Tracy – Collective Imperial <strong>Defence</strong>: The Laboratory For Trans-Nationalism.Dr John Mordike – <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> Priorities 1880-1914: the Nation and the Empire.Dr Peter Overlack – “A Vigorous Offensive”: Core aspects of <strong>Australian</strong> Maritime <strong>Defence</strong>Concerns before 1914.Dr Michael Evans – Strategic Culture and the <strong>Australian</strong> Way of War: Past, Present and FuturePerspectives.RegistrationFormal registration for the conference will open in <strong>May</strong> <strong>1999</strong>. The cost of attendance is likely to beapproximately $120.Early indications of likely attendance, or requests to be included on conference information distribution lists,should be lodged with:Mr Dave GriffinKing-Hall Naval ConferenceNaval History DirectorateCP3-4-41Department of <strong>Defence</strong>CANBERRA ACT 2600Telephone: (02) 6266 2654Facsimile: (02) 6266 2782Email: navy.history@dao.defence.gov.au

Images from the Back Seat is a collection ofsome of the more interesting airbornephotographs taken by <strong>Defence</strong> photographerDenis Hersey.Some of the images portrayed in thispublication have been used for publicitypurposes. However, many have never beenpublished before.The majority of the collection is of Royal<strong>Australian</strong> Air <strong>Force</strong> aircraft past and present.There is also a fine display of air-to-airphotographs of aircraft from the Army andNavy as well as aircraft from New Zealand,Britain, Italy, United States and Singapore.The book is available from the office of the<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> at a cost of $19.95.<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> – Mail Order FormIMAGES FROM THE BACK SEATPlease send order to <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>,B-4-26, Russell Offices, CANBERRA ACT 2600Name:Address:I enclose a cheque or money order payable to the Receiver of Public Monies for $being payment for copies of Images from the Back Seat.

Strategy and CrisisBy Brigadier J J A Wallace, AM“Mistakes in operations and tactics can becorrected, but political and strategic mistakes liveforever.”Allan R Millet and Williamson Murray 1IntroductionMallet and Murray’s statement is a potentreminder of the imperative for decision makersat the highest levels to get it right. But if it’s true forthe conduct of routine national affairs, then it is evenmore important in crisis. While we no longer livewith the immediate fear of incidents degenerating intoa nuclear exchange, the stakes in national securitycrises remain high. A benign interstate securityenvironment only works to increase the relativepolitical and moral value of individual life, when it issuddenly threatened by terrorism or intrastateviolence. National prestige forfeited in the inepthandling of crisis is not easily recovered, particularlywhen the adversary is no match in terms of power.Yet crises are increasingly characteristic of thecontemporary security landscape. As guerrilla warsonce exploited the inability of major powers tomobilise an appropriate response from largeconventional military forces, today’s crises seek toexploit the cumbersome nature of their inevitablylarge conventional bureaucracies. Minor powers andeven terrorist groups, often lead the national crisismanagers of powerful countries a merry chasethrough international institutions and media, just ashandfuls of guerrillas once lead their armies throughjungles. Strengthening the analogy is the fact thatdespite the weight of technical, intellectual andpolitical resources being heavily in their favour,national bureaucracies, and their masters, have largelyfailed to come to terms with the nature of thischallenge and the potentially pivotal role of strategy.The problem lies first in the very nature of bothcrisis and strategy. The dynamics at work in crisisdirectly attack the decision-making process, andparticularly in large bureaucracies. In addition, crisisexhibits, as Coral Bell has identified, “the asymmetryof decision-making” 2 and therefore doesn’t lend itselfto prescriptive analysis. In this it is similar to strategy,which Luttwak describes as “pervaded by aparadoxical logic of its own, standing against theordinary linear logic by which we live in all otherforms of life.” 3 It is perhaps not surprising then thatstrategy is so little understood. To some it is simplylong term planning or any action at the strategic level,while in reality it is much more, and is certainly anindispensable element in any competitive activity.This article maintains that despite theacknowledged difficulty of being prescriptive ineither the analysis of crisis or the application ofstrategy, a better understanding of the two can benefitcrisis management. 4 More than this, there is a windowof opportunity in the early stages of most crises,where by the use of some simple models, strategy canbe applied so as to ameliorate many of crisis’snegative effects.CrisisMuch time and academic effort have beendevoted to defining crisis. However for the purposesof this article, dealing as it is within a national securitycontext, Hermann’s definition is appropriate:“Specifically, crisis is a situation that (1)threatens high priority goals of the decisionmakingunit, (2) restricts the amount of timeavailable for the response before the decision istransformed, and (3) surprises the members of thedecision-making unit by its occurrence.” 5Threat, time and surprise therefore become thekey determinants of crisis. Experience generallyproves that while there might be some short termstimulus and benefit from mild increases in the threator time constraint, significant adverse movement inany of these factors over time will place additional,mainly negative pressures on the decision unit andcrisis management process. 6,7 This becomesparticularly relevant at the national strategic level,where the stakes are such that perceptions of threatimpose disproportionate pressures of themselves,even without the impact of the other two dimensions.These pressures, described as “disruptive stress” 8 by

14AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE JOURNAL NO. <strong>136</strong> MAY/JUNE <strong>1999</strong>Hermann and Brady, impact on the performance ofboth individuals and organisations.At the individual level, the most obvious effect ofdisruptive stress is fatigue, which though it effectseach individual differently, generally reduces mentalperformance, and increases irritability, paranoia anddefensiveness. The result is reduced individual andteam effectiveness, and a tendency to seek simpleoptions and entertain fewer alternatives. At the sametime the triggering of natural defensive mechanismsunder stress, can cause otherwise incisive thinkers togive undue weight to “expert” advice and to findrefuge in value judgments and precedent.Unfortunately however, national security crises do notlend themselves to such simplistic default action.Each situation is usually unique and the consequencesof error too critical. In addition, national crisis almostinevitably demands a strategic long term view, evenwhile dealing with the immediate. But under thestress of crisis, there is a strong predilection forsolving the short term problem and ignoring thelonger and often more strategically relevantconsequences. 9The major effect of disruptive stress onorganisations is that senior decision makers take auncharacteristic interest in even minor issues and theirmanagement; what Hermann calls “a contraction inauthority”. 10 This has both positive and negativeeffects on the management of crisis. On the positiveside it increases the responsiveness of otherwisebureaucratic structures, cutting out unnecessarylevels, and also increasing the possibility of moreinnovative solutions. The tendency to use a small coremanagement group, increases security and thereforeenhances negotiating flexibility, while also permittinggreater control. But over reliance on a few key playerscan also increase the vulnerability of the organisationto fatigue, and too much secrecy can limit thediversity and integrity of information. 11 The verystatus and direct influence of the decision makers,may interfere with the efficient operation ofcommunication and information channels and causethem to be overloaded, as subordinates responddirectly to key players in an ad hoc hierarchy. In theend, whether the balance of effects is positive ornegative, is very much personality dependent, but it isprudent to plan for the worst case. 12In the case of national security crises, we canpredict with reasonable certainty the institutions andtherefore general types of individuals who are likelyto play key roles in crisis management. There can belittle doubt that the individual and organisationalparadigms within which the key players formulatestrategy, will impact significantly on its quality. Onedescription of crisis as “the imposition of acumulation (sic) of nasty events on passive authoritiesand decision-makers”, 13 suggests that those who willinevitably deal with national crisis are perhaps, insome important ways, the least suitable.Politicians will have the major impact, but whereboth national strategy and crisis demand a long termand usually internationalist view, politicians have,understandably, a predominantly short term and oftendomestic perspective. Bureaucrats will also play a keyrole. However while the requirement is for innovativeand speedy decision-making, the internal dynamics atwork in bureaucracies often cause them to rationalisetheir actions in terms of: “most crises resolvethemselves”, refuge in procedures and a sometimesoverriding interest in preserving the good name of theorganisation and ensuring its internal operationsremain intact. 14 The military will be prominent inmatters of national security, and although its officersare usually better skilled in strategy than their civiliancounterparts, it suffers all the same symptoms ofbureaucratic inertia, and in some cases shows too littleempathy for political imperatives.But if this is the nature of crisis, then as importantis to understand the essential processes taking place.Crises do not occur in a vacuum. They are manifest inthe failure or frustration of other channels ofinteraction, usually conventional diplomatic ones.They are, with apologies to Clausewitz, thecontinuation of negotiation by other means. Thestakes and/or criticality have been raised by one partyor group of parties, to force, if not their position onthe other, then at least his immediate consideration ofit. It is then, as Bouchard maintains, “a series ofbargaining interactions” 15 between two or more sides.There is a competition at play, where no one is likelyto have exclusive control of events, but where each isattempting to resolve the situation in his interest. Inthis competition the instigator of the crisis willinitially hold the initiative. He can be expected toretain it and keep the other side reactive, unless losingit through error or the premeditated action of theopponent. In the final analysis, given the phenomenaof contraction of authority discussed above, thisbargaining or competition may actually be betweenjust a few individuals in each of the participatingparties. 16Therefore the nature of crisis, and particularlynational security crisis, is such that the balance offorces is against the exercise of effective decisionmakingand management. Figure 1. summarises thekey effects of crisis on decision-making. The aimmust be to maximise the potential positive dynamicsof crisis, while at least mitigating its negative impacts.

STRATEGY AND CRISIS15Mandating processes will not do, as the seniority ofthe players is such that they have the authority tooverturn procedures and are likely to do so under theinevitable pressures of crisis. Instead we mustintroduce a new dynamic, a stronger inherent logic,something that focuses action without limiting itsoptions and is relevant to the essentially bargainingprocess which is crisis.THE MAJOR EFFECTS ONDECISION-MAKING IN CRISISPOSITIVE EFFECTSIncreased responsivenessEnhances innovationEnhances flexibilityNEGATIVE EFFECTSNarrowing of OptionsOver reliance on “experts”Refuge in value judgmentPoor mental performanceOverloaded communicationsMeddling in lower levelsReduced team performanceLack of long term viewFigure 1A Role For StrategyFigure 2 suggests four key functions necessary toredress or enhance as appropriate, the effects of crisison decision-making. Establishing and maintaining arelevant focus for activity becomes a major function,because the negative psychological consequences ofdisruptive stress, mainly affect the ability of bothindividuals and organisations to focus on the realsituation. The fatigue factor is essentially a result ofactors assuming too deep a scope of responsibility.Although difficult to mandate, anything that can limitthis, can separate functions, will reduce both thefatigue on key players and on those lower in theorganisational chain disrupted by their suddenattention. The two remaining functions areimperatives for crisis management. They must bepresent to acknowledge the strategic realities innational security crises and the fact that crisismanagement is essentially a competitive bargainingprocess. It is precisely the concern of strategy forthese four functions, that provides its utility in crisis.MAXIMISING/MINIMISING THE EFFECTS OF CRISISCOMPENSATINGPOSITIVE EFFECTS FUNCTIONS NEGATIVE EFFECTSREQUIREDFocus on ActualSituationNarrowing of OptionsOver reliance on “experts”Maintain Separationof FunctionsMaintain LongTerm ViewRefuge in value judgmentPoor mental performanceOverloaded communicationsMeddling in Lower LevelsReduced team performanceLack of Long Term viewIncreased responsivenessEnhances innovationEnhances flexibilityMaintainTempoFigure 2

16AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE JOURNAL NO. <strong>136</strong> MAY/JUNE <strong>1999</strong>StrategyA major reason for the inadequate command ofstrategy by national bureaucracies, has been itsmonopolisation as a subject of study, by soldiers andmilitary academics. This has served neither the soldiernor civilian well. To use Liddell Hart’s definition ofstrategy as: “the art of distributing and applyingmilitary means to fulfil the ends of policy”, 17 is tosuggest that it is somehow the unique province of thesoldier and only starts when the matter is handed tohim. For the soldier the danger is that the definitionevokes such military imagery, that he can too easilyfind refuge from tackling its deeper sense, byresorting to the more familiar ground of tactics.Instead the start point needs to be the definition inits ordinary usage of “skilful management in gettingthe better of an adversary or attaining an end.” 18 Theessential notion is that strategy is applied in acompetition between two or more players; and thatthat competition is in fact a contest of wills.Clausewitz and Liddell Hart used the images ofboxers and wrestlers respectively to evoke thisdynamic in strategy. The strength and relevance of theimage being in the personal interplay between the twocontestants, the fact that each is locked inconcentration on the other in an effort to pre-empt orcounter every move. Unfortunately the impact of thisanalogy tends to be lost with the inevitableremoteness of the strategist from the field and/or thefact that the medium of competition is sometimes theless demonstrably competitive environment of policy.But holding onto this image of being engaged in acompetitive struggle is an essential first step in theeffective formulation and application of strategy; andin crisis a most appropriate one, given its essentiallycompetitive bargaining nature.Equally important, and illustrated by the sameanalogy, is the personalisation of the opposition. It isno coincidence that both boxers and wrestlers lock onto each others eyes. What the arms and legs do isinevitably forecast in the eyes. The boxers intensity insearching behind the eyes, must be copied by thesuccessful strategist. But to get inside the mind of theopponent, you must first personalise him. Too oftenthe opposition is seen and treated as a country or anorganisation, without identifying in it, or if necessaryattributing to it, the personality essential to focus thestrategist. The sense of competition is too easily lostwithout this essential step, and strategy quicklysacrificed to the application of procedures or plans.As we have seen by the contraction of authoritycharacteristic of crisis, there is perhaps moreopportunity to exploit this subtle but essential aspectof applying strategy here, than in more routineactivity where the opposition’s decision-makingfunction may be more diffuse.The image of strategy being exercised in acompetitive environment, and the need to personalisethe opposition, are important tools in assisting crisismanagers to focus on the actual situation. Howeverbefore identifying more of strategy’s potentialcontribution in crisis, it is necessary to determine itsvarious dimensions and functions. Like so muchmilitary terminology, these have become confused inthe dual usage of the word in its military and ordinarycontext. Strategy has two dimensions, both relevant,whether it is being applied in a military or generalsense. They have been described as: “the verticaldimension of the different levels that interact with oneanother; and the horizontal dimension of the dynamiclogic that unfolds concurrently within each level.” 19The vertical dimension of strategy can itself havemany layers. 20 However while the detailed functionsin each may vary, the overriding purpose of thestrategic level does not. Its principle purpose is toidentify and initiate the campaigns necessary toachieve political or policy objectives. In doing this itprovides directives, usually in broad terms, andcreates the necessary strategic environment, includingensuring adequate resources, so that the next level ofcommand can achieve the intent of the strategic level.If properly understood and exercised, this functionwill more than occupy strategic crisis managers andso provide a natural delineation between theirs’ andtheir subordinate levels’ responsibilities. However inpractice it is as much observed in the breach, and thenmore through misunderstanding of the functions andresponsibilities of the levels below, than through lackof trust in them.The levels below the strategic are in militaryparlance the operational and tactical levels. Butputting aside the language, the importance is in theirfunctions, which have equal relevance in the civildomain. The significance of the operational level isthat it takes the broad direction of the strategic leveland designs a coordinated sequence of tacticalactivities to achieve it. It might in a national crisis be aMission or Embassy or a special team dispatched orplanned to be dispatched to the general area of thecrisis. Its value is in its proximity to the crisis andlocal knowledge, or at least focus. This places it in thebest position to respond in a timely way to rapidlychanging circumstances and to identify appropriatetactical activities to achieve the higher direction.Nonetheless, it too eschews as much detail as

STRATEGY AND CRISIS 17possible, making this the responsibility of the tacticallevel of command, whose activities it directs,facilitates and coordinates. In this context thesetactical activities may range from on-site negotiation,to military action.If properly understood and applied, this verticaldimension of strategy contributes to crisismanagement in two main ways. First it frees eachlevel to focus better on the actual situation byreducing the scope of its responsibility. Secondly, byseparating functions, it reduces fatigue and thenegative impacts of the inevitable contraction ofauthority in crisis, which is essentially the result ofkey players not understanding the role of the strategiclevel, but at the same time being under incrediblepressure to do something. Of course this verticalrationalisation of responsibility can always beoverturned on the whim of personality under theinherent pressure of crisis, but the deeper theunderstanding, the less this is likely. 21The horizontal dimension of strategy followsnaturally from the acceptance of it being applied in acompetitive environment. This notion provides the“dynamic logic” that should be acting throughoutevery level of an operation or crisis solving activity. Itis the process of outthinking the opposition andmanipulating both him and the situation to achieveour ends. Although speaking of its application to war,von Moltke well captures the more general sense ofthis second dimension of strategy:“Strategy is a system of expediencies. It is morethan a science; it is the application of knowledgeto practical life, the development of an originalleading idea in response to constantly changingcircumstances; it is the art of action underpressure of the most difficult circumstances.” 22This concept of it providing an original leadingidea in response to constantly changingcircumstances, together with its being applied in apersonalised competitive environment, are the crux ofits relevance to crisis management at the strategiclevel. The absence of a leading idea at this levelinevitably leaves the whole organisation wallowingpassively in procedures. Its presence gives focus. Thisleading idea must be kept out in front by the adoptionof a long term view and maintaining tempo.The adoption of a long term view is inherent inthe vertical dimension of strategy and reinforced inthe horizontal. It is implicit that the highest level, thestrategic, adopt the longest view. But this is notrestricted to the time frame for dealing with theimmediate problem, or the legitimate need to providelead time for action at the subordinate levels. Evenmore important is to retain sight of our long termnational objectives. As the opposition will usuallyhave initiated the crisis as an alternate means ofachieving his otherwise frustrated long term aims, it isessential that our response not contribute to his aim bydefault. The Clinton administration’s response toIraq’s incursions into the UN Safe Haven in Sep 96, isan example where the immediate political andstrategic advantages of being seen to be tough withSaddam, had the potential to put long term objectivesat risk. The correct application of strategy demandsnot losing sight of the long term aim, and framingresponses to the immediate problem in this context.At the same time the need to outthink theopponent, the horizontal dimension of strategy,demands a long term view in a different sense. Byconstantly focusing on the desired end state, thecircumstances we wish to prevail at the end of thecrisis, the successful strategist shapes the near andmid term situation to his own advantage. Taking along view causes him to anticipate developments anddrives his information requirements, naturallyassisting him to build on the most valuablecommodity for the strategist, foreknowledge. Butwithout the ability to apply it in a timely manner, toestablish a tempo of decision-making and actionfaster than the opposition, even the best strategy isoften doomed to failure.Establishing and maintaining tempo 23 in theapplication of strategy is an essential drawn from itsbasically competitive nature. The aim is not justanticipation for its own sake, but to render theopposition’s actions irrelevant because they wereframed for old circumstances, which we have sincechanged or caused to be changed. Therefore while thesheer speed of our responses can contribute to tempo,the strategist has additional, more subtle tools. If forinstance as Wylie observes “we deliberately make histheory invalid, we have gone a long way to makinghis actions ineffective”, 24 and have therefore gotteninside his decision cycle, thus establishing superiortempo. In the same indirect way, if we can slow hisdecision-making process, perhaps by complicating it,we have achieved a relative advantage in tempo. Asindicated in Figure 2., the function of maintainingtempo seeks to maximise the few positive effects ofcrisis. As it happens, it is a fundamental objective ofstrategy and applying strategy in crisis will reinforcethis function well.Therefore strategy potentially provides a verypowerful tool for crisis management. Its real utility isin the fact that it provides a compensating dynamic tothe inherently disruptive forces characteristic of crisis.More practically it reinforces four functions critical to

18AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE JOURNAL NO. <strong>136</strong> MAY/JUNE <strong>1999</strong>overcoming these negative forces while enhancing itspositive consequences. But those thrown into thebreach in times of crisis are seldom if ever experts incrisis management or strategy. If for all the logic ofapplying it, we are to hope to see strategy actuallyused in crisis, then initial crisis managementprocedures and expectations by key players mustfacilitate it naturally. This is not to suggest mandatingprocedures for the duration of the crisis. But in thatinitial few hours of chaos, even the most senior andcompetent executives are naturally looking for someframework in which to act. If one can be providedthat facilitates their thinking strategically from theoutset, the natural dynamics of strategy may well takeover. Even if it doesn’t withstand the disruptiveeffects of crisis in the long term, such a start to crisismanagement will be of immeasurable benefit as thesituation unfolds.Getting a Strategic Start in CrisisThe lack of reliable information at the outset ofany crisis is usually so pronounced that remedying itbecomes the focus of even the highest level planners,often distracting them from their real responsibilities,and inviting the contraction of authority andpreoccupation with detail we should be seeking toavoid. Instead the paucity of information should beseen as an advantage. The reality is that at this pointstrategic planners only need to know what hashappened in the most general sense in order to fulfiltheir responsibilities. They need to know how this actor situation might affect national security andtherefore what their objective should be in dealingwith it. Precisely because of the paucity of accurateinformation and also to allow maximum flexibility forsubordinate levels, this objective should not be set inconcrete terms, but expressed as the intent of thegovernment.Crafting this intent therefore becomes the firstresponsibility of the strategic level. It must becarefully done and will deal not so much with themeans the Government might use, but be anexpression of its resolve, and most importantly detailthe conditions it requires to prevail after resolution ofthe crisis. The aim is to incorporate implicit ratherthan explicit qualifications on the means that might beused. An example of an intent for a hostage taking bya renegade group in a foreign country (“Seeland”)might be:The Government’s intention is to achieve the saferelease of the hostages, while reinforcing theauthority and sovereignty of the Seelandgovernment and without heightening the residualthreat to <strong>Australian</strong> nationals and expatriatesafter resolution of the incident.It is immediately obvious that such a statement isnot reliant on the detail of the situation, but on theintention of the Government. It incorporates thestrategic imperatives and a longterm view. It is robust,and while making clear the main objective of gainingthe safe release of the hostages, implies constraintsthat will be as relevant whether the eventual solutionlies in diplomatic or military action. Its utility forcrisis managers is that it sets important parameterswithin which to operate as more information comes tohand. It allows skilled analysts and staff to alreadyidentify the type of information that might be requiredand in broad terms, the types of contingencies theyshould be considering. Most importantly it provideseveryone a focus.Having crafted our intent the second step is todetermine the opposition’s. It might appear that thisshould be done before deciding our own, but at thestrategic level I believe not. The incident has beeninitiated to disturb the status quo. While in the courseof the crisis we may be forced to accept acompromise solution, or even see advantage in doingso, 25 to be responsive to the opposition from the outsetis to cede the initiative. In the absence of detailedinformation, it is initially both valid and relevant touse the status quo as our reference point. Validbecause to do nothing is to risk slipping into aresponsive mode and relevant because he will haveinitiated the crisis in order to disturb a status quo thatfavoured us more than him. In the absence of reliableinformation, this makes the re-establishment of thestatus quo a reasonable immediate aim for us. This isnot to ignore the realities of the situation. Howeverthe significance of our focusing on the actualsituation, is to take account of it in achieving ourintent, not just in responding to the crisis andparticularly the opposition’s manipulation of usthrough it.Like ours, the opposition’s intent can usually bedetermined from its broad strategic context before allthe details of the incident are available. While it isimportant to identify the opponent’s actual purpose ininstigating the incident, it may only be possible to listhis likely objectives at this stage. These first two stepsare the first order issues in the model at Figure 3.As we move down the left and right hand sides ofthe model, we are looking to ensure that howeverchaotic conditions become, or whatever side issueshave to be dealt with on the way, that like the boxer,we are all the time seeking to weaken his position

STRATEGY AND CRISIS19while defending ours. We examine our intent and hisobjectives, and decide for each, the thing or thingsthat are critical to their achievement. These are ourrespective Centres of Gravity. Those things that ifaccessed or manipulated by one side, could cause theother to fail in his intent or objectives. 26 In some caseseach sides Centre of Gravity may be the same. Forinstance in the hypothetical hostage example, thesupport of the Seeland government could be the mostcritical factor for both sides. However more often theywill be different, and the Centre of Gravity for thehostage takers in this case could be the support of athird country sponsor. But having determined therespective Centres of Gravity, our aim is to focus asmuch of our activity as possible on manipulating his,while ensuring at the same time that ours is protected.ARRIVING AT AN INITIAL STRATEGY IN CRISISDetermine the Govt/StrategicIntentDetermine Opponent’sObjectivesDetermine Our Centre ofGravityInformationRequestsDetermine HisCentre of GravityIdentify How to ProtectOur Centre of GravityIdentify How toManipulate HisCentre of GravitySelect Most EffectiveCombinations of EffectsINITIALSTRATEGYFigure 3To achieve this requires discerning the activitiesor avenues through which the Centres of Gravity canbe manipulated. These general activities are termedDecisive Points, for the effect they can have on theCentre of Gravity. For each of these Decisive Pointsspecific activities are then identified to generate orreinforce these effects. This process need not beexhaustive at this point. If the aim is ensure focus,then discipline must be exercised by considering onlythe more effective and efficient methods. Staff canprovide more detailed analysis latter. The logic of thisprocess is illustrated in Figure 4.

@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e @@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@e?@@h?@@@@@@h?@@h?@@@@@@h?@@h?@@@@@@h?@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@g@@g@@g@@g@@g@@g@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@?@@?@@?@@?@@?@@?@@?@@@@@@@@?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@e?@@@@@@@@?e@@@@@@@@ ?@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@20AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE JOURNAL NO. <strong>136</strong> MAY/JUNE <strong>1999</strong>THE LOGIC LINK BETWEEN CENTRE OF GRAVITY,DECISIVE POINTS AND ACTIVITIESThird countrysponsorship of terroristsCENTRE OFGRAVITYIncrease DiplomaticCost for SponsorIncrease FinancialCost to SponsorEtcDECISIVEPOINTSMeans*General Assemblymotion*Seeland dip protest*etc*****MeansFigure 4****MeansACTIVITIESThe final step in arriving at the initial strategy is toselect those activities that provide the most effect, thatmanipulate the more important Decisive Points.Economy of effort will also be a consideration here,and some activities may be selected for the fact thatthey impact on more than one Decisive Point. Iftempo is to be established quickly, priority may alsobe given to some activities because of the speed withwhich they can be initiated, even though otheractivities may replace them later.This combination of activities, together with ageneral scheme for their implementation, is the initialstrategy. It will invariably be modified in execution asmore information comes to hand, but allows bothindividuals and the organisation to respond purposelyand with the best chance of avoiding the disruptiveeffects of crisis. Importantly, as the model at Figure 3.shows, each of these stages generates informationrequests, that both help focus intelligence agenciesand facilitate the early validation of the originalassumptions.ConclusionMost studies of the subjects of crisis and strategyhave failed to bridge the gap between theory andpractice. The asymmetry of the concepts complicatesthis necessary step in both cases. However it is thevery fact that both have been described as art notscience, 27 that makes strategy a natural partner forcrisis. Crisis resists order and strategy should never bemore ambitious than to try to use or shape chaos.Instead of seeking to control chaos, it provides theleading idea and trails a central thread around whichcrisis teams can manoeuvre to advantage throughcrisis.National security crises may have lost some of theportent of catastrophe they held in Cold War days, butthe interests and prestige of nations and coalitions stillride on the success with which they are managed. Ifcrisis managers acknowledge from the outset thatcrisis is a competitive bargaining process, and use itsearly hours to establish both a strategic orientationand intent, we will see far more successful outcomes.Hopefully this model will assist in this process.NOTES1. Allan R. Millet & Williamson Murray. “The lessons of war”, inThe National Interest (Winter 1988).2. Coral M. Bell, “Decision-making by governments in crisissituations”, in International Crises and Crisis Management, ed.Daniel Frei, Saxon House, 1978, p. 50.3. Edward Luttwak, “The logic of strategy”, in War, ed. LawrenceFreedman, Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 195.4. For the handling of short notice national security crises, I amusing the term “crisis management” throughout as Snyder andDiesing do to include coercive diplomacy. See: James L.Richardson, “Crisis management: a critical appraisal”, in NewIssues in International Crisis Management, ed. Gilbert R.Winham, Westview Press, Boulder, 1988, pp. 15-16.0

STRATEGY AND CRISIS215. Charles F. Hermann, International Crises: Insights FromBehavioural Research, Free Press, NY, 1972, p. 13.6. James A. Robinson, “Crisis: an appraisal of concepts andtheories”, in Charles F. Hermann (ed.), 1972, p. 33.7. Charles Hermann’s account of laboratory tests of the effects ofheightening these factors appeared to challenge this hypothesis.However even he questioned the validity of the results. See:Charles F. Hermann, “Threat, time, and surprise: a simulationof international crisis”, in International. Crises: Insights FromBehavioural Research, pp. 207-208.8. Hermann and Brady refer to disruptive stress as: “the defectiveoperation of a person’s coping mechanisms – such asmisconception or rigidity in cognitive processing.” See: CharlesF. Hermann, & Linda P. Brady., “Alternative models ofinternational crisis behaviour”, in International Crises: InsightsFrom Behavioural Research., p. 284.9. Ole R. Holsti, “Time, alternatives, and communications: the1914 and Cuban missile crises”, in Charles F. Hermann (ed.),1972, p. 63.10. Charles F. Hermann, “Threat, time, and surprise: a simulationof international crisis”, p. 196.11. Charles F. Hermann & Linda P. Brady, p. 268.12. The effects of crisis on the performance of both organisationsand individuals are discussed in detail in International Crises:Insights From Behavioural Research, edited by Hermann. Seeparticular: James A. Robinson, “Crisis: an appraisal of conceptsand theories”, pp. 33-35; Thomas W. Milburn, “Themanagement of crises”, pp. 263-266; and Charles F. Hermann& Linda P. Brady, pp. 283-90.13. Uriel Rosenthal & Pert Pijnenburg, Crisis Management andDecision-Making Oriented Scenarios, Kulwer AcademicPublishers, Dordecht, 1991, p. 1.14. Ian I. Mitroff & Christine M. Pearson, Crisis Management – ADiagnostic Guide for Improving Your Organisation’s Crisis-Preparedness, Jossey-Bass, San Fransisco, 1993, p. 25.15. Joseph F. Bouchard, Command in Crisis, Columbia UniversityPress, 1991, p. 2.16. As Coral Bell illustrates by the Cyprus crisis in 1974, there areusually more than two major players in a crisis. This has anexponential effect on the considerations and interests that mightbe vying for satisfaction. See: Coral M. Bell, pp. 50-51.17. Michael Howard, “The dimensions of strategy”, in War, ed.Lawrence Freedman, Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 197.18. The Macquarie Concise Dictionary, 2nd edn, 1994, p. 990.19. Edward N. Luttwak, Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace,Bekanap Press Harvard, 1987, p. 70.20. The military hierarchy of strategy has been variously described,but has included:a. The Grand or National Strategic level, where allelements of national power are considered.b. The Military Strategic level, where all the elements ofmilitary power are considered. (Note that anyfunctional area of government could be substitutedhere for the word “military” e.g. foreign affairs, police,or attorney generals; to reflect the strategic level of thatfunction.)c. Theatre Strategic level, where a subordinate HQ hassome strategic responsibilities, usually including intheatrepolitical liaison.21. The need for this vertical separation of responsibility in crisismanagement has also been identified by students of crisis.Legadec describes the two functions as “strategy constructionand implementation”, and emphasises the need to maintain acritical distance between them throughout a crisis. See: PatrickLagadec, Preventing Chaos in Crisis, trans. Jocelyn M. Phelps,McGraw Hill, 1993, p. 184.22. Helmuth Von Moltke, “Doctrines of war”, Lawrence Freedman(ed.), 1994, p. 220.23. Tempo is not speed, but the rate at which decisions are madeand enacted. This has been variously described as a “DecisionCycle or Loop”, and in Lind’s account of decision-making incombat, as an “OODA Loop” (Observe, Orientate, Decide,Action). See: William S. Lind, Maneuver Warfare Handbook,Westview Press, 1985, pp. 5-6.24. J.C. Wylie, Rear Admiral USN, Military Strategy: a GeneralTheory of Power Control, <strong>Australian</strong> Naval Institute Press,Sydney, 1967, p. 110.25. Crisis should not only be seen as a threats, it may provideopportunities to enhance our interests, in ways or areas notnormally available. In fact the Chinese word for crisis meansboth threat and opportunity. See: Thomas W. Milburn, p. 270.26. Purists would argue that there can only be one Centre ofGravity at each level for each protagonist. This generallyapplies in a military strategic analysis, where the solution liesmainly in the application of force. However it is not always sosimple an issue, when considering the broader and more subtleinstruments of national power. Nonetheless it is advantageous,for the focus it provides, to have only one Centre of Gravity ateach level of possible and appropriate.27. For crisis see: Coral M. Bell, p. 51. For strategy see: RobertO’Neil, “An introduction to strategic thinking”, in The Makingof Strategy, Murray, Knox, Bernstein (eds.), CambridgeUniversity Press, 1994, p. 30.Brigadier Jim Wallace graduated into the Royal <strong>Australian</strong> Infantry from the Royal Military College in 1973. He has served in the 8/9thBattalion RAR, and the Special Air Service Regiment which he commanded from 1988 to 1990. He is a graduate of both the British ArmyStaff College and the <strong>Australian</strong> College of <strong>Defence</strong> and Strategic Studies. Brigadier Wallace was Commander Special <strong>Force</strong>s from 1993to 95 and has recently handed over command of 1st Brigade in Darwin to become the Director General of Land Development. He has seenservice in UNTSO in the Middle East and has previously had an article published in the <strong>Journal</strong> of Strategic Studies, London.

THE FLIGHT OF THE PIGThe Flight of the Pig, a full colour publicationdepicts the F111 fighter aircraft in all its glory.The book traces the history of the aircraft overits 25 years of faithful duty with the RAAF.<strong>Defence</strong> Photographer Mal Lancaster, who hashad an affinity with the F111 since its arrival inAustralia has spent the best part of his careerphotographing the “Pig” as the F111 isaffectionately known.The book is available through the office of the<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> at a cost of$29.95.<strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong> – Mail Order FormTHE FLIGHT OF THE PIGPlease send order to <strong>Australian</strong> <strong>Defence</strong> <strong>Force</strong> <strong>Journal</strong>,B-4-26, Russell Offices, CANBERRA ACT 2600Name:Address:I enclose a cheque or money order payable to the Receiver of Public Monies for $being payment for copies of The Flight of the Pig.